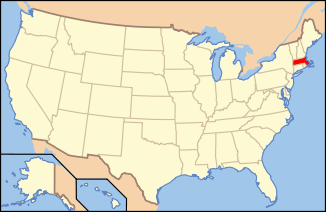

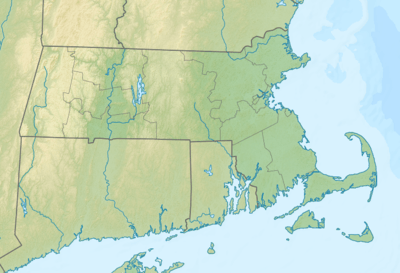

Lowell National Historical Park

Lowell National Historical Park is a National Historical Park of the United States located in Lowell, Massachusetts. Established in 1978 a few years after Lowell Heritage State Park, it is operated by the National Park Service and comprises a group of different sites in and around the city of Lowell related to the era of textile manufacturing in the city during the Industrial Revolution. In 2019, the park was included as Massachusetts' representative in the America the Beautiful Quarters series.[2]

| Lowell National Historical Park | |

|---|---|

The Boott Cotton Mill & Museum | |

| |

| Location | Lowell, Massachusetts, United States |

| Nearest city | Lowell, Massachusetts |

| Coordinates | 42°38′48″N 71°18′37″W |

| Area | 141 acres (57 ha) |

| Established | June 5, 1978 |

| Visitors | 520,452 (in 2011)[1] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Lowell National Historical Park |

History

- See the History of Lowell, Massachusetts article for a detailed history of the city

First settled by Europeans in the 17th century, East Chelmsford (later renamed Lowell in honor of the founders' deceased business partner) became an important manufacturing center along the Merrimack River in the early 1820s. It was seen as an attractive site for the construction of a planned industrial city, with the Middlesex Canal (completed in 1803) linking the Merrimack to the Charles River, which flows through Boston, and with the powerful 32' Pawtucket Falls. The already existent Pawtucket Canal, designed for transportation around the Pawtucket Falls on the Merrimack, became the feeder canal for a 5.6-mile long system of power canals based around the falls. Unlike many other mill towns, however, Lowell's manufacturing facilities were built based on a planned community design. Specifically Lowell was planned as reaction to the mill communities in Great Britain, which were perceived as cramped and inhumane. Some called it the "Lowell Experiment," which was an attempt at creating a manufacturing center with a combination of production efficiency with democratic morals and social structure.[3]

Initially the factories of Lowell were built with ample green space and accompanying clean dormitories, in a style that anticipated such later architectural trends as the City Beautiful movement in the 1890s. Lowell attracted both immigrants from abroad and migrants from within New England and Quebec (including a large proportion of young women, known as Lowell mill girls) who lived in the dormitories and worked in the mills.

The textile industry in New England experienced a sharp decline after World War II and by the 1960s, many of the Lowell's textile mill buildings were abandoned. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, several important forces came together from which emerged the Lowell National Historical Park. Congressman F. Bradford Morse assisted in the city's selection for "Model Cities" status; Brendan Fleming, UMass Lowell (UML) Math Department faculty member, after his election to the Lowell City Council proposed the first Historic District "The Mill and Canal District" which was approved in 1972; Gordon Marker, Executive Director of Model Cities and an urban planner, was instrumental in designing the concept for an Urban Park based on Historic Preservation and Economic Revitalization; Patrick Mogan, Education Administrator and later Superintendent of Schools, was primarily interested in Lowell's children and strongly advocated the preservation and sharing of their cultural experiences; and the Lowell Historical Society which opened the Lowell Museum in 1976. Together these circles of interest became a collaborating force led by United States Senator and Lowell native Paul Tsongas to enact legislation for a national park. In 1978, the United States Congress established the Lowell National Historical Park, the Lowell Historic Preservation District, and the Lowell Historic Preservation Commission.

In 1990, The Trust for Public Land assisted the National Park Service in acquiring 3 acres for the purpose of housing the headquarters for the Lowell National Historical Park.[4]

Legislative History of Lowell

Lowell National Historic Park was established by the Lowell Establishment Act in 1978. Lowell National Historical Park was established due to its significant cultural and historical sites and structures. This significance of these cultural and historical sites and structures symbolized aspects of the Industrial Revolution. Lowell is also represented to be the most significant planned industrialized city in the United States, which is a very important historical aspect in United States history. Another factor is that the immigration of different ethnic groups during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was represented in Lowell’s neighborhoods. Preserving this area of land would allow for these representations to still be preserved in Lowell’s neighborhoods. Even though the city of Lowell had a large budget for cultural and historical preservation, they would still need the assistance of the federal government to ensure that all necessary early buildings and structures were preserved. The extra protection and funding by the federal government will allow for the preservation of these lands. By establishing Lowell as a National Park that is protected by the federal government, the history and significance of the Industrial Revolution, as well as cultural aspects would be preserved and shared with present and future generations.

In 2012, The Lowell National Historical Park Land Exchange Act of 2012 was added to the original legislation to allow for land within park boundaries to be exchanged with land owned by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the city of Lowell, or the University of Massachusetts building authority. Lowell National Historic Park is an originally established park and did not replace a previously established site.

Administrative History of Lowell

Chronological Order of Superintendents: 1. Lewis S. Albert: 1978-1980 2. James L. Brown: 1980-1981 3. John J. Burchill: 1981-1984 4. Lawrence D. Gall: 1984-1984 5. Chrysandra “Sandy” L. Walter: 1984-1992 6. Rich Rambur: 1993-1999 7. Patrick McCrary: 1999-2005 8. Michael Creasey: 2005-2012 9. Peter Aucella: 2012-2012 10. Celeste Bernardo: 2012-Present

Regional Affiliation in Chronological Order 1. North Atlantic Region: 1978-1995 2. Northeast Region: 1995-2018 3. Northeast Atlantic-Appalachian Region: 2018-Present

Park information

Lowell Trolley | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Among the notable features of the park are:

- Boott Cotton Mill and Museum

- The Francis Gate

- Pawtucket Dam and Gatehouse

- Suffolk Mill Turbine and Powerhouse

- Kirk Street Agents House

- Mill Girls and Immigrants Boardinghouse

- The Lowell Canal System

- Swamp Locks, Lower Locks, Guard Locks

- Merrimack River and Northern Canal Walkway

- The Worthen House

The park includes a visitor center, as well as many restored and unrestored sites from the 19th century. The visitor center provides a free self-guided tour of the history of Lowell, including display exhibits such as the patent model of a loom by local inventor S. Thomas.

A footpath along the Merrimack Canal from the visitor center is lined with plaques describing the importance of various existing and former sites along the canal. The Boott Mills along the Merrimack River, on the Eastern Canal, is the most fully restored manufacturing site in the district, and one of the oldest. The Boott Mill provides a walk-through museum with living recreations of the textile manufacturing process in the 19th century. The walking tour includes a detour to a memorial to local author Jack Kerouac, who described the mid-20th century declined state of Lowell in several of his books. A walkway along the river leads to several additional unrestored mill sites, providing views of restored and unrestored canal raceways once used by the mills. Additionally, the park includes the Patrick J Mogan Cultural Center, which focuses on the lives of Lowell's many generations of immigrants. Other exhibits include a working streetcar line,[5][6] canal boat tours exploring some of the city's gatehouses and locks, and the River Transformed / Suffolk Mill Turbine Exhibit, which shows how water power, the Francis Turbine, ran Lowell's textile factories.

Current Challenges

There is a common theme in the challenges that Lowell has passed in the past decade, and this is lack of funding from the government. In February of 2013, Congress was discussing five percent budget cuts for the National Park Service. The National Parks that would have been affected by these budget cuts, including Lowell, needed to create reports about how they would “absorb” these budget cuts. The effects from the budget cuts were not 100% clear at the time, but based on what this budget was used for, there would be large impacts on the staff within the park. One of the impacts they discussed for staffing would’ve been “a hiring freeze in place and the furloughing of permanent staff.”

In December of 2013, the government shutdown had a major impact on the budgets in Lowell. During this time, only a few security and maintenance workers were able to still work in the park, meaning all of the interpretation staff was not. Without the presence of these staff members, all tours, boat rides, etc. could not occur. This shutdown also had a large impact on the budget for the park, as well as how many fulltime staff members they could pay. However, Lowell had one mission and that was to “focus on its major programs.” Lowell has a Folk Festival every year as well as a Summer Music Series. These are large events that Lowell looks forward to every year and they both bring in a lot of money for the city. So even though it would be a challenge, Lowell was still willing to fight and find a way to have their major events occur. This article also discusses a major point that relates back to the other article I discussed in the previous paragraph. There was a decrease in both permanent and seasonal positions in the park within a two-year period, and at this point in time, there were 80 people working in the park full time and about 12 seasonally. With these reductions and limitations, there were workers performing tasks outside their scope of knowledge, as well as causing some attractions hours to be cut shorter during the day.

In December of 2014, superintendent Celeste Bernardo was faced with the conflict of possibility having to increase the fees for education programs and boat rides within the park. It was not something she wanted to do but needed to find a solution to a budget cut problem that would “make things better.” This meaning that they did not need the increase in fees to save the park. They wanted to increase the fees so that the money could be used to improve the park. This park took a huge hit when it came to budget cuts within a 6-year period. In 2008, Lowell had 88 permanent employees within the park. That number was dropped to 66 in 2014 due to these dramatic budget cuts. The biggest conflict they had with this fee increases what that they wanted to keep these prices low for those people who live in areas of poverty. Lowell is within a city that has these areas and wanted to keep it a place where all people could comfortably enjoy the park. People from the community were able to share their opinions on a public discussion board online. Lowell continues to struggle with budget cuts to this day.

Photo gallery

.jpg) U.S. President Jimmy Carter (center) with Ted Kennedy (left) and Paul Tsongas signs the creation of Lowell National Historical Park, 1978

U.S. President Jimmy Carter (center) with Ted Kennedy (left) and Paul Tsongas signs the creation of Lowell National Historical Park, 1978 Authentic Looms in the Boott Cotton Mill and Museum

Authentic Looms in the Boott Cotton Mill and Museum The Boott Cotton Mill and Museum and Park Trolley

The Boott Cotton Mill and Museum and Park Trolley The Park offers boat tours of the historic Lowell Canal System

The Park offers boat tours of the historic Lowell Canal System The River Transformed Exhibit at the Wannalancit Mill

The River Transformed Exhibit at the Wannalancit Mill Park Headquarters, Paige Street

Park Headquarters, Paige Street

See also

- Society for the Establishment of Useful Manufactures

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Lowell, Massachusetts

References

- "National Park Service Visitor Use Statistics". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-10-06.

- "LOWELL NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK QUARTER". US Quarters. January 2014. Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- Cathy., Stanton (2006). The Lowell experiment : public history in a postindustrial city. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1558495460. OCLC 63297733.

- "Lowell National Historical Park". The Trust for Public Land.

- "APTA Streetcar and Heritage Trolley Site - Lowell, Massachusetts". American Public Transportation Association and the Seashore Trolley Museum. February 2013. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- "U.S. Streetcar Systems- Massachusetts Lowell". U.S. Streetcar Systems Website. RPR Inc. November 23, 2011. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lowell National Historical Park. |

- Official Lowell National Historical Park website

- Lowell National Historical Park 2009 Annual Report

- Heritage Preservation and Development White Paper: A 30 Year Assessment of Lowell National Historical Park

- Presentation of Lowell Stories White Paper: A 30 Year Assessment of Interpretation and Education at Lowell National Historical Park

- Building America's Industrial Revolution: The Boott Cotton Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- The Lowell Experiment: Public History in a Postindustrial City by Cathy Stanton (ethnographic study of the work of Lowell NHP)

- Mill Power: The Origin and Impact of Lowell National Historical Park by Paul Marion 2014