Trams in Adelaide

Until 1958, trams formed a network spanning most of Adelaide, with a history dating back to 1878. Adelaide ran horse trams from 1878 to 1914 and electric trams from 1909, but has primarily relied on buses for public transport since 1958. Electric trams and trolleybuses were Adelaide's main public transport throughout the life of the electric tram network. All tram services except the Glenelg tram line were closed in 1958. The Glenelg tram remains in operation and has been progressively upgraded and extended since 2005.

| Trams in Adelaide | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Adelaide, South Australia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

Adelaide's first tramway was opened in 1878; a succession of horse-drawn services followed until in 1907 the South Australian Government established the Municipal Tramways Trust (MTT), which bought out their private-sector owners. A year later the MTT operated its first electric tram and before long the entire network was powered by electricity.

The early use of trams was for recreation as well as daily travel, by entire families and tourists. Until the 1950s, trams were used for family outings to the extent that the MTT constructed gardens in the suburb of Kensington Gardens, extending the Kensington line to attract customers. By 1945 the MTT was collecting fares for 95 million trips annually — 295 trips per head of population.

After the Great Depression, the maintenance of the tramway system and the purchase of new trams suffered. Competition from private buses, the MTT's own bus fleet and the growth of private car ownership all took patrons from the tram network. By the 1950s, the tram network was losing money and being replaced by an electric and petrol-driven bus fleet. Adelaide's tram history is preserved by the volunteer-run Tramway Museum, St Kilda[1] and the continuing use of 1929 H type trams on the remaining Glenelg tram line.

The Glenelg line was extended to Adelaide railway station in 2007 and to Adelaide Entertainment Centre in 2010. The upgrade included the first new tram purchases in more than 50 years. Flexity Classic and Citadis 302 trams now run on the line.

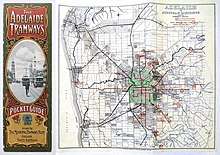

Horse trams

In early 1855, less than twenty years after the colony was founded, South Australia's first horse tram began operating between Goolwa and Port Elliot on the Fleurieu Peninsula.[2] Just over twenty years later Adelaide became the first city in Australia to introduce horse trams, and eventually the last to discard them for more modern public transport.[3] Although two trials of street level trains were run, the state of Adelaide's streets, with mud in winter and dust in summer, led to the decision that they would not be reliable.[4]

Sir Edwin Smith and William Buik, both prominent in Kensington and Norwood Corporation then Adelaide City Council (and both later mayors of Adelaide), spent some time inspecting European tramways during the 1870s. They were impressed with horse tram systems and, on returning to Adelaide, they promoted the concept leading to a prospectus being issued for the Adelaide and Suburban Tramway Co (A&ST). Private commercial interests lobbied government for legislative support, over Adelaide council's objections related to licensing and control. As a result, the Government of South Australia passed an 1876 private act, authorising construction of Adelaide's first horse tram network.[5] It was scheduled for completion within two years, with 10.8 miles (17.4 km) of lines from Adelaide's city-centre to the suburbs of Kensington and North Adelaide.[6] Completed in May 1878,[7] services began in June from Adelaide to Kensington Park with trams imported from John Stephenson Co of New York, United States.[8]

Until 1907, all horse tram operations were by private companies, with the government passing legislation authorising line construction. Growth of the network and rolling stock was driven largely by commercial considerations. On the opening day, the newly founded A&ST began with six trams, expanding to 90 trams and 650 horses by 1907 with its own tram manufacturing facility at Kensington.[9]

A Private act, passed in September 1881, allowed the construction of more private horse tramways and additional acts were passed authorising more line construction and services by more companies.[3] Most of the companies operated double-decker tram, although some were single level cabs with many built by John Stephenson Co, Duncan & Fraser of Adelaide, and from 1897 by the A&ST at Kensington.[9] The trams ran at an average speed of 5 miles per hour (8 km/h), usually two horses pulling each tram from a pool of four to ten.[10]

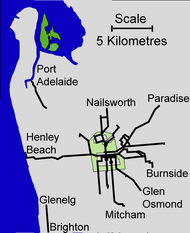

Horse tram network

.jpg)

Various companies expanded the network from its initial line to Kensington, with eleven companies operating within six years, three more having already failed before constructing tracks.[11] The Adelaide to North Adelaide line opened in December 1878, a separate one from Port Adelaide to Albert Park in 1879, Adelaide to Mitcham and Hindmarsh in 1881, Walkerville 1882, Burnside, Prospect, Nailsworth and Enfield in 1883, and Maylands in 1892.[12] Various streets were widened especially for the tram lines including Brougham Place, North Adelaide by 10 feet (3 m) and Prospect Road to a total width of 60 feet (18 m).[13][14]

All but one line was built in 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge with the exception from Port Adelaide to Albert Park. This line was built in 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm) to accommodate steam engines, also requiring some of the line to be raised on embankments to avoid swampy ground and flooding.[15] There were 74 miles (119 km) of tramlines with 1062 horses and 162 cars by 1901[16] and isolated lines from Port Adelaide to Albert Park and Glenelg to Brighton, as well as a network joining many suburbs to Adelaide's CBD by 1907.

The network had termini in Henley Beach, Hindmarsh, Prospect, Nailsworth, Paradise, Magill, Burnside, Glen Osmond, Mitcham, Clarence Park, Hyde Park and Walkerville.[17] To accommodate the specific needs of horses, most streets were left unsealed. The horses' urine needed an unsealed surface for absorption and their hooves a soft surface for good traction.[10]

First electric trams

Adelaide's first experiment with electric powered trams was a demonstration run on the Adelaide and Hindmarsh Tramway company's line. A battery powered tram fitted with Julien's Patent Electric Traction[18][19] ran in 1889 to Henley Beach. The trial was unsuccessful due to the batteries poor capacity, and the promoters' deaths in a level crossing accident shortly after precluded further experiments.[20]

As with horse trams, commercial interests pursued government support for the introduction of electric tramways. The most influential was the "Snow scheme", promoted by Francis H. Snow largely on behalf of two London companies, British Westinghouse and Callender's Cable Construction. The scheme involved the purchase of major horse tramways, merging into an electric tramway company with twenty-one years of exclusive running rights. Legislation was passed in 1901, a referendum held in 1902, but the required funds had been spent and the scheme collapsed. Adelaide's council proposed their own scheme backed by different companies, but couldn't raise the required capital, and J.H. Packard promoted various plans of his own devising that also never eventuated.[21]

By 1901, Adelaide's horse trams were seen by the public as a blot on the city's image. With a population of 162,000 the slow speed of the trams, and the lines subsequent low traffic capacity, made them inadequate for public transport needs. The unsealed roads the horses required became quagmires in winter and sources of dust in summer. The 10 pounds of manure each horse left behind daily, was also not well regarded.[10] Under these various pressures the government negotiated to purchase the horse tramway companies. A 28 March 1906 newspaper notice announced that the government had purchased all of the city tramways for £280,000.[16] Bill No.913, passed 22 December 1906, created the Municipal Tramways Trust (MTT) with the authority to build new and purchase existing tramways.[22]

Not all tramway companies were purchased, as the Glenelg to Marino company continued operating separately until its failure in 1914.[23] The government purchased the properties, plant and equipment of existing tramways but did not purchase the companies themselves.[22] The equipment included 162 trams, 22 other vehicles and 1,056 horses. By 1909 at the launch of Adelaide's electric tram services there remained 163 horse trams and 650 horses under the control of the MTT.[24]

Due to the time required to electrify the network, the MTT continued to run horse trams until 1914. The cost of purchasing the tramways was funded by treasury bills[22] and the act capped total construction costs at £12,000 per mile of track.[25] £457,000 was let in contracts to March 1908 for construction of the tramways, trams, strengthening the Adelaide bridge over the River Torrens and associated works.[26] The official ceremony starting track construction was in May 1908, with tracks originally laid on Jarrah sleepers.[27]

On 30 November 1908, there were two trial runs from the MTT's depot on Hackney Road to the nearby Adelaide Botanic Garden and back, the evening trial carrying the Premier and Governor.[27] At the official opening ceremony on 9 March 1909, Electric Tram 1 was driven by Anne Price, wife of Premier Thomas Price, from the Hackney depot to Kensington and back, assisted by the MTT's chief engineer.[28]

Municipal Tramways Trust

The MTT was established in 1906 as a tax-exempt body with eight members, mostly by appointed local councils but with some government appointees.[29] They established a 9 acres (3.6 ha) tram depot site near the corner of Hackney Road and Botanic Road with a depot building, twenty-four incoming tracks and a large administration office.[30] William Goodman was appointed as its first engineer, later general manager and remained as general manager until his 1950 retirement.[31]

To cater for family outings the MTT constructed gardens in the current suburb of Kensington Gardens, extending the Kensington line to attract customers.[32] By 1945 the MTT was collecting fares for 95 million trips annually, representing 295 trips per head of population (350,000).[33]

By 1958 the tram network was reduced to just the Glenelg tram line (see Mid-century decline section). The MTT continued to operate most of the local bus routes in the inner metropolitan area. In 1975 the services of the MTT became the Bus and Tram division of the State Transport Authority and the MTT ceased to exist.[24]

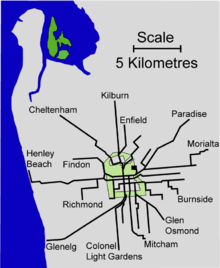

Electric tram network

At the 1909 opening, 35 miles (56 kilometres) of track had been completed with electricity supplied by the Electric Lighting and Supply Co.[34] The electric tram system ran on 600 Volts DC supplied at first from two converter stations,[35] No.1 converter station on East Terrace with 2,500 kW of AC to DC capacity and No.2 station at Thebarton with a capacity of 900 kW.[36] To cope with variable loads on the system, very large storage lead–acid batteries were installed, the initial one at East Terrace comprising 293 cells and a 50 ton tank of sulphuric acid.[37]

The Glenelg line was, from 1873, a 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm) steam railway that ran at street level into Victoria Square.[38] Originally privately owned it was taken over by the South Australian Railways then transferred to the MTT in 1927. The line was closed to be rebuilt to 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge, electrified at 600 Volts DC and converted to tramway operation, reopening in late 1929.

The Port Adelaide line, which until that time had still used horse trams, began to be converted to electric operation in 1914 and opened 3 April 1917[24] A line from Magill to Morialta opened in 1915 for weekend tourist traffic with only a single return service on weekdays. The line ran in the valley of 4th creek, a tributary of the River Torrens, across farmland and along unmade and ungazetted roads.[39]

All services on the Morialta line were replaced by buses in 1956. The last tram line built in Adelaide was the Erindale line which opened in early 1944.[33] At maximum extent the lines connected Adelaide with the sea at Henley Beach, Grange and Glenelg, reached the base of the Adelaide Hills at Morialta and Mitcham and had Northern and Southern limits of Prospect and Colonel Light Gardens.[40]

Electric tram types

From 1908 to 1909, 100 electric trams were manufactured by Duncan & Fraser of Adelaide[32] at a cost of approximately £100 each.[41] Up to its last tram purchase in 1953, the MTT commissioned over 300 electric trams, some of which remained in service for over 75 years. The first of 11 Bombardier Flexity Classic trams were introduced in January 2006, followed by the first of six Alstom Citadis trams in December 2009. A further three Citadis trams entered service in 2018.[42][43]

Trolleybuses

During the Great Depression the MTT needed to expand services but finances prevented laying new tracks. A decision was made to trial trolleybuses, and a converted petrol bus began running experimentally on the Payneham and Paradise lines in 1932. A permanent trolleybus system opened in 1937, and trolleybuses continued running until July 1963.[44]

Mid-century decline

From 1915 onwards the MTT had to compete against unregulated private buses, often preceding the trams on the same route to steal fares, which the MTT countered by opening their own motor bus routes from 1925.[45] The South Australian government began regulating buses within the state in 1927, although some private operators argued that Section 92 of the Constitution of Australia, which deals with interstate matters, exempted them from following the regulation. By notionally marking each ticket as a fare from the pickup point to Murrayville, Victoria (but allowing passengers to board or alight sooner) companies avoided having to abide by the regulation for some time.[46] The case was considered by the High Court, during the course of which Justice Isaac Isaacs offered a temporary compromise agreed to by both parties, but it appears that a final judgment was never delivered.[47] Eventually, most of the affected bus operators sold their buses to the MTT or other operators who followed the routes described.[46] Up until the end of World War I, most Adelaideans were dependent on public transport for daily journeys. The introduction of private automobiles decreased passenger numbers until petrol rationing during World War II led to a resurgence in patronage; patronage remained higher than before the war, until rationing was discontinued in 1951.[48]

From the start of the great depression until the closure of the network only one lot of trams was purchased by the MTT. Due to shortages there was minimal maintenance of the network during World War II and post-war shortages prevented the purchase of new trams.[49] In 1951–1952 the MTT lost £313,320 and made the decision to convert the Erindale, Burnside and Linden Park lines to electric trolleybuses. The last trams on these lines ran on 24 May 1952 with the lines lifted from 18 April 1953. A 1953 royal commission was held to inquire into the financial affairs of the MTT resulting in a completely reconstituted board.[50] Late the same year, with driver safety concerns about the conflict with increasing traffic on the road, the Glen Osmond line was temporarily converted to motor buses. The line was never converted back to trams and much comment was made about the continuing maintenance of unused overhead lines.[51]

Trolley buses gradually made way for motor buses until the last electric tram or bus service ran on 12 July 1963 leaving only the Glenelg line as a remnant of a once extensive light rail network.[52] Except for the Glenelg Type H, the trams were sold or scrapped. Some were used as shacks, playrooms or preserved by museums.[41]

Renaissance and expansion

A 1.2-kilometre (0.75 mi) extension of the line from the Victoria Square terminus was announced in April 2005, which would see trams continue along King William Street and west along North Terrace through Adelaide railway station and the western city campus of the University of South Australia. An additional two Flexity Classic trams were ordered to cater for the expanded services. Construction commenced in 2007 and a new Victoria Square stop, relocated from the centre of the square to the west, was opened in August 2007. Testing of the extension began in September 2007 before it was officially opened on 14 October 2007 with shuttle services along the new extension until the release of the new timetable on 15 October when normal through services commenced.[53] A free City Shuttle service between South Terrace and City West also began on 15 October to complement the main Glenelg to City West service.[54] Further extensions at that time were the subject of public debate; Tourism Minister Jane Lomax-Smith expressed support for the line to be extended to North Adelaide and Prospect although the Transport Minister stated that this was not a practical option,[55] with his preferred option the creation of a fare free city loop.[56]

In the 2008 state budget, the government announced that it would extend the tram line further. The first extension, completed in early 2010, was from the existing North Terrace terminus to the Adelaide Entertainment Centre in the inner north-west suburb of Hindmarsh, with a park and ride service set up on Port Road.[57] Following the expected electrification of the Outer Harbour and Grange rail lines, new tram-trains were proposed to run to West Lakes, Port Adelaide and Semaphore by 2018.[58] However, these plans were later scrapped in the 2012 state budget.[59]

In 2017, another stage of expansion was announced, adding a four-way tram junction at the intersection of North Terrace, King William Street and King William Road. One further stop would be provided north of that junction, adjacent to the Adelaide Festival Centre, and three to the east of it near the South Australian Museum, University of Adelaide and East End at the new eastern terminus in front of the old Royal Adelaide Hospital. The project was expected to cost $80 million with the contract awarded to a joint venture of Downer Rail and York Civil. Preliminary works began in July 2017 with major works commencing in October.[60][61][62] The extensions opened on 13 October 2018, seven months behind schedule,[63] with the stop at the end of the eastward line known as Botanic Gardens owing to its proximity to Adelaide Botanic Garden.[64]

In July 2019, the government announced the provision of tram services would be contracted out, along with other transport services in Adelaide.[65] In July 2020, Torrens Connect commenced operating Adelaide's trams under an eight-year contract.[66][67][68]

Routes

Glenelg tram

The Glenelg tram system dates back to 1929 when it was converted from heavy rail to tram operation; the route between Victoria Square and Glenelg was the only part of the original tram network to survive the closures of the twentieth century. It connects the beachside suburb of Glenelg to the Adelaide city centre. Originally terminating at Victoria Square, the system has been extended periodically with its most recent expansion opening in October 2018.

21st century extensions

Through the twenty-first century there have been a number of proposals to expand the tram network both within and beyond the city centre.

In 2016, the Weatherill Government released a report detailing a proposal under the name "AdeLINK" that listed five routes that would radiate from a new CityLINK city centre loop: an eastern 🌍 route to Magill; a collection of north western 🌍 routes; a northern 🌍 route to Kilburn; a southern 🌍 route to either Mitcham or Daw Park; and a western 🌍 route to Adelaide Airport.[69] The PortLINK proposal, that would replace the Outer Harbor railway line with light rail, is reminiscent of a previous extension proposal to West Lakes, Port Adelaide and Semaphore that was announced in the 2008 South Australian Budget but later abandoned in the 2012 budget.[70][59]

Following the 2018 state election, the incoming Marshall Government abandoned the previous AdeLINK proposal, announcing that they would instead develop the network within the city centre only, announcing a vision of four routes: Glenelg to North Adelaide via the existing Glenelg line; Entertainment Centre to Central Market through the eastern half of the city; a loop service operating from Glenelg along the existing Glenelg line and through the eastern half of the city; and the existing South Terrace to Royal Adelaide Hospital "City Shuttle" service.[71][72] The proposed city loop service from Glenelg would require the King William Street-North Terrace intersection to be reconstructed with a right-hand turn from King William Street to the eastern side of North Terrace, which the Liberals had announced during its campaign. This would have required the junction relaid in December 2017 to be dug up and replaced.[73] The right-hand turn project was cancelled in November 2018 due to rising costs and engineering challenges.[74]

On 13 October 2018 the tram extension eastwards along North Terrace, known as the Botanic line, became operational.[75]

Current rolling stock

H type

Until January 2006, 1929-vintage H type trams provided all services on the Glenelg line. These trams were built for the electrification of the line and have many of the characteristics of North American interurban cars of the same period. Thirty H type trams were built by a local manufacturer A Pengelly & Co, with road numbers 351 to 380.

Twenty-one remained in service in 2005.[76] After the arrival of the Flexity Classics, five H-class trams were refurbished in 2000 with the remainder disposed of.[77] By 2012, three were in store at Mitsubishi Motors Australia's Clovelly Park plant.[78] The remaining two were refurbished by Bluebird Rail Operations, one briefly operating weekend services in August 2013.[79][80] The only other recorded use of the pair was in February 2015 when they operated a charter.[81] To make room for new Alstom Citadis trams at the Glengowrie depot, in December 2017 both were moved to the Department of Planning, Transport & Infrastructure's Walkley Heights facility.[82]

Flexity Classic

A contract for nine Bombardier Flexity Classic trams was awarded to Bombardier in September 2004.[83] The first three arrived at Outer Harbor on 15 November 2005. One (103) had been damaged in transit when machinery shifted on board the ship during a storm and was despatched to Bombardier's Dandenong plant for assessment. It was later declared beyond economic repair and became a source of spare parts at Glengowie depot with a replacement built.[84]

The other two were unloaded at Victoria Square on 22 November 2005. Following a period of commissioning and staff training both entered service on 9 January 2006.[84] The remainder were landed at Port Melbourne, moving to Adelaide by road. The last of the original nine arrived in Adelaide in September 2006.[85]

A further two were added to the order in 2005 following the decision to extend the line along King William Street.[86][87] Both arrived in the first half of 2007, 111 being diverted to Yarra Trams' Preston Workshops and completing over 400 kilometres of trial running on the Melbourne network.[88] The replacement 103 arrived in June 2007.[89]

Another four were ordered in June 2008 as part of the Adelaide Entertainment Centre extension, entering service in 2011/12.[90][91] Numbered 101–115, all were built by Bombardier in Bautzen, Germany.

Citadis 302

In May 2009 the State Government purchased six Citadis 302 five-car trams for $36 million. Manufactured by Alstom in La Rochelle, France, they had been ordered for the Metro Ligero system in Madrid, Spain, but became surplus following the line they were ordered for being scaled back.[92][93] Most had not been used.[94]

The trams were delivered in two separate batches of three being landed in Melbourne on 9 September 2009 and 10 November 2009 for modifications at Preston Workshops before being moved by road to Adelaide.[95][96] In December 2017 a further three arrived.[97][98]

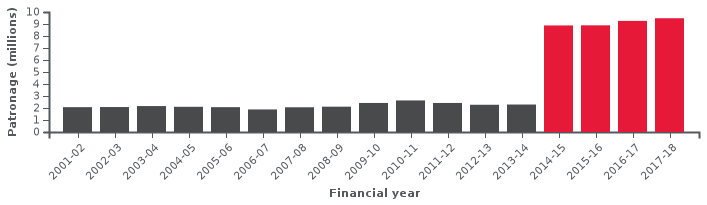

Patronage

The following table lists patronage figures for the network (in millions of boardings) during the corresponding financial year. Australia's financial years start on 1 July and end on 30 June. Major events that affected the number of boardings made, or of how patronage was measured, are included as notes.

| Year | N/A | 2001-02 | 2002-03 | 2003-04 | 2004-05 | 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patronage (millions) |

2.07 | 2.08 | 2.16 | 2.10 [lower-alpha 1] |

2.07 [lower-alpha 1] |

1.88 | 2.06 [lower-alpha 2] |

2.11 | 2.42 [lower-alpha 3] | ||

| Reference | [99] | [100] | [101] | [102] | [103] | [104] | [105] | ||||

| Year | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | |||

| Patronage (millions) |

2.63 | 2.42 | 2.27 | 2.29 | 8.88 [lower-alpha 4] |

8.89 | 9.26 | 9.48 | |||

| Reference | [106] | [107] | [108] | [109] | [110] | [111] | [112] | [113] | |||

Seniors free travel included (other free travel excluded)

All free travel included | |||||||||||

- Line closed for upgrade during June & July 2005

- City Centre extension opened in October 2007

- Entertainment Centre extension opened in March 2010

- All free travel included (previously, only seniors free travel was included)

See also

References

- "Adelaide Tramway Museum at St. Kilda". Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- The Critic (1909), p.6

- The Critic (1909), p.8

- Kingsborough L.S. (1965), p.2

- Radcliffe, I.C. (1974), p.23

- The Critic (1909), p.7

- Lewis H. (1985), p.139

- Hickey A. (2004), p.16

- Steele C. (1981), p.11

- Steele C. (1986), p.5

- Kingsborough, L.S. (1965), p.8

- Horse tram line opening dates from Steel C. (1981), p.10, The Critic (1909), p.9-11, Nagel P. (1971), P.50 and Lewis H. (1985), p.139

- Nagel P. (1971), p.50

- Lamshed M. (1972), P.30

- Kingsborough L.S. (1965), p.17

- The Critic (1909), p.14

- 1945 map of the 1907 Horse tramways, Published by the MTT and created by L.S. Kingsborough and C.J.M. Steele. Kingsborough L.S. (1965), p.85

- US patent 384447

- US patent 384580

- Australian Electric Transport Museum (1974), p.24

- Radcliffe, I.C. (1974), pp.31-33 and The critic (1909), p.13

- The Critic (1909), p.15

- Kingsborough L.S. (1965), pp.43-44

- State Transport Authority (1978)

- The Critic (1909), pp.17-18

- The Critic (1909), pp.19-21

- The Critic (1909), p.21

- The Critic (1909), p.37

- The Critic (1909), pp.15,17-18

- The Critic (1909), p.27

- McCarthy, G.J (22 June 2005). "Goodman, William George Toop (1872–1961)". The University of Melbourne eScholarship Research Centre. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- Steele C. (1981), p.15

- Steele C. (1981), p.37

- The Critic (1909), p.23

- The Critic (1909), p.32

- The Critic (1909), p.34

- The Critic (1909), p.35

- State Transport Authority (1979), p.9

- Steele C. (1986), p.43

- The Municipal Tramways Trust Adelaide (1952), Electric Transport System Map

- Oldland, Jenny (16 January 2007). "Tram 104 departs Foul Bay". Yorke Peninsula Country Times. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- SA mid-year budget review: $20 million for more Adelaide trams and a new spur line ABC News 15 December 2016

- Here & There Trolley Wire issue 352 February 2018 page 19

- The Tramway Museum, St Kilda (S.A.) (Undated), information brochure on tram fleets

- Steele C. (1981), p.23

- Steele C. (1981), p.32

- "Murrayville" Buses, The Observer, 14 July 1928.

- Steele C. (1986), pp.23,43

- Steele C. (1981), p.42

- Steele C. (1981), p.43

- Steele C. (1981), P.45

- Steele C. (1981), P.47

- Official opening for tram extension ABC News 14 October 2007

- Adelaide's Tramway Extension Opens Trolley Wire issue 311 November 2007 pages 3-8

- Bildstien, Craig (23 January 2007). "Minister 'mortified' by ruling on trams". Adelaide Now. News Limited. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- "Free tram network 'to drive city's future". The Advertiser. News Limited. 19 February 2007. p. 2.

- "Park 'n' Ride Users - 7 days". Adelaide Entertainment Centre. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- "2008 State Budget". South Australian Department of Treasury and Finance. 5 June 2008. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- "Port, Semaphore tramline derailed in State Budget". The Advertiser/AdelaideNow. 8 May 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Kemp, Miles (21 July 2017). "New tram stops and extra funding to ease traffic problems announced for North Terrace extension". The Advertiser. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- North Terrace services detoured for tram line extension works Adelaide Metro

- "Major construction set to begin on $80 million City Tram Extension Project". Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. 18 September 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- Boisvert, Eugene (13 October 2018). "Surprise start for Adelaide's long-delayed tram extension". ABC News. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "New tram services now operating". Adelaide Metro. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- SA government to privatise operation of Adelaide Metro trains and trams ABC News 1 July 2019

- Adelaide Bus and Public Transport Contracts Announced Australasian Bus & Coach 10 March 2020

- Welcome to a new era for public transport in South Australia Department of Planning, Transport & Infrastructure 20 March 2020

- UGL and John Holland to operate Adelaide trams Metro Report International 12 March 2020

- "AdeLINK Multi-Criteria Analysis Summary Report" (PDF). Department of Transport, Planning and Infrastructure. 2016. pp. 10–19.

- "2008 State Budget". South Australian Department of Treasury and Finance. 5 June 2008. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "People Focused Public Transport" (PDF). Liberal Party of Australia (South Australian Division). Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Siebert, Bension (9 March 2018). "Libs won't rebuild Adelaide's suburban tram network". InDaily. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- MacLennan, Leah (8 March 2018). "Liberal Party promises to add right-hand turn to Adelaide tram line". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- "SA Liberals can't get Adelaide tram to go right". ABC News. 18 November 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- "New tram services now operating". Adelaide Metro. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Trams TransAdelaide

- Glenelg Tram Refurbishment Project Trolley Wire issue 285 May 2001 pages 16-19

- Adelaide tram news Trolley Wire issue 328 February 2012 page 16

- H-Class tram to return to the Glenelg to Adelaide tramline Adelaide Advertiser 27 July 2013

- H type trams won’t be brought back into service despite successful trial The Australian 15 February 2014

- Here & There Trolley Wire issue 341 May 2015 page 22

- Here & There Trolley Wire issue 352 February 2018 page 19

- "Metros" Railway Gazette International December 2004 page 820

- Adelaide's New Trams Trolley Wire issue 304 February 2006 pages 16, 17

- Adelaide news Trolley Wire issue 307 November 2006 page 26

- Cabinet, Subjects for Consideration, 8 August 2004 Department of the Premier & Cabinet

- City West to Glenelg Service Archived 24 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine Tramway Museum, St Kilda

- Adelaide - another Flexity enters service Trolley Wire" issue 309 May 2007 page 16

- Adelaide: last Flexity arrives Trolley Wire" issue 310 August 2007

- Additional trams Trolley Wire issue 314 August 2008 page 15

- Entertainment Centre, Hindmarsh to Glenelg Service Archived 24 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine Tramway Museum, St Kilda

- Castello, Renato (24 May 2009). "European trams to bolster our City-Glenelg fleet". The Adelaide Advertiser. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- Fenton, Andew (7 June 2009). "Six new trams for Adelaide-ex-Madrid". The Adelaide Advertiser. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- Six new trams for Adelaide Trolley Wire issue 318 August 2009 page 21

- New European trams a massive boost to Adelaide network Rail Express 24 June 2009

- "Photos of Madrid tram at Preston". Trams Down Under archive. 10 September 2009."Another Madrid Citadis". Trams Down Under archive. 11 November 2009."Madrid tram to Adelaide". Trams Down Under archive. 11 November 2009.

- Job lot as new trams heading to SA The Independent Weekly 18 October 2017

- More Spanish trams arrive Catch Point issue 243 January 2018 page 18

- "TransAdelaide - Replacement Pages - Rail Patronage - Report 2002-2003" (PDF). Parliament of South Australia. 4 December 2003. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "TransAdelaide Annual Report 2004-05" (PDF). TransAdelaide. p. 11. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "TransAdelaide Annual Report 2005-06" (PDF). TransAdelaide. p. 22. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "DTEI Annual Report 2006-07" (PDF). Department for Transport, Energy and Infrastructure. p. 70. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "DTEI Annual Report 2007-08" (PDF). Department for Transport, Energy and Infrastructure. p. 121. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "DTEI Annual Report 2008-09" (PDF). Department for Transport, Energy and Infrastructure. p. 118. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "DTEI Annual Report 2009-10" (PDF). Department for Transport, Energy and Infrastructure. p. 75. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "DTEI Annual Report 2010-11" (PDF). Department for Transport, Energy and Infrastructure. p. 62. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "DPTI Annual Report 2011-12" (PDF). Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. p. 68. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "DPTI Annual Report 2012-13" (PDF). Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. p. 78. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "DPTI Annual Report 2013-14" (PDF). Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. p. 88. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "DPTI Annual Report 2014-15 - Transport Acts". Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "DPTI Annual Report 2015-16" (PDF). Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. p. 63. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- "DPTI Annual Report 2016-17 - Reporting against the Passenger Transport Act 1994". Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- "DPTI Annual Report 2017-18 - Adelaide Metro patronage 2017-18". Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- Australian Electric Transport Museum (1974). Australian electric transport museum, St Kilda, South Australia.

- Hickey, Alan (editor) (2004). Postcards: On the Road Again. Wakefield Press. ISBN 1-86254-597-9.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Kingsborough, L.S. (1965). The horse tramways of Adelaide and its suburbs, 1875–1907. Adelaide: Librararies board of South Australia.

- Lamshed, Max (1972). Prospect 1872–1972, A portrait of a city. Adelaide: The corporation of the city of Prospect. ISBN 0-9599015-0-7.

- Lewis, H. John (1985). ENFIELD and The Northern Villages. The corporation of the city of Enfield. ISBN 0-85864-090-2.

- Metropolitan tramways trust (1974). The Adelaide tramways, pocket guide. A catalogue of rolling stock 1909–1974. Adelaide: Metropolitan tramways trust.

- Metropolitan tramways trust (1975). 1907–1974 Development of street transport in Adelaide, Official history of the municipal tramways trust. Adelaide: Metropolitan tramways trust.

- Nagel, Paula (1971). North Adelaide 1937–1901. Adelaide: Austaprint. ISBN 0-85872-104-X.

- Radcliffe, I.C.; Steele C.I.M. (1974). Adelaide road passenger transport, 1836–1958. Adelaide: Libraries board of South Australia. ISBN 0-7243-0045-7.

- State Transport Authority (1979). Adelaide Railways. Adelaide: State Transport Authority.

- State Transport Authority (1978). Transit in Adelaide : the story of the development of street public transportation in Adelaide from horse trams to the present bus and tram system. Adelaide: State Transport Authority. ISBN 0-7243-5299-6.

- Steele, Christopher (1981). The burnside lines. Sydney: Australian Electric Traction Association. ISBN 0-909459-08-8.

- Steele, Christopher (1986). The Tramways and Buses of Adelaide's North-East Suburbs. Norwood, South Australia: Australian Electric Traction Association. ISBN 1-86252-089-5.

- Taylor, Edna (2003). The History and Development of ST KILDA South Australia. Salisbury, South Australia: Lions Club of Salisbury. ISBN 0-646-42219-7.

- The Critic (1909). The Tramways of Adelaide, past, present, and future : a complete illustrated and historical souvenir of the Adelaide tramways from the inception of the horse trams to the inauguration of the present magnificent electric trolley car system. Adelaide: The Critic.

Further reading

- Eardley, Gifford (June 1961). "The Adelaide and Hindmarsh-Henley Beach Tramway Company". Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin.

- Eardley, Gifford (May 1974). "The Adelaide, Unley and Mitcham Tramway Company". Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin.

External links

- Adelaide's Tram History

- Adelaide Tramway Museum at St. Kilda

- TMSV's acquired H type

- Bendigo Tramway Museum

- Sydney Tramway Museum's acquired H type

- Glenelg tram rebuild and commissioning of the Flexity type trams

- Curious Adelaide: Why was Adelaide's tram network ripped up in the 1950s?, Candice Prosser, ABC, 1 December 2017.