Road transport in Australia

Road transport is an essential element of the Australian transport network, and enabler of the Australian economy. Australia relies heavily on road transport due to Australia's large area and low population density in considerable parts of the country.[1]

Another reason for the reliance upon roads is that the Australian rail network has not been sufficiently developed for a lot of the freight and passenger requirements in most areas of Australia. This has meant that goods that would otherwise be transported by rail are moved across Australia via road trains. Almost every household owns at least one car, and uses it most days.[2]

Victoria is the state with the highest density of arterial roads in Australia.

Costs and funding

Funding and responsibility for Australia's road network is split between the three levels of government; Federal, State and Local. Because of long distances, low population densities, and widely separated major settlements, the costs of and funding for roads in Australia has been, historically, a major fiscal issue for all levels of government, especially Federal and State. The popular phrase 'the tyranny of distance', also the title of a famous historical work,[3] captures the central role of transport in Australian policy, producing many conflicts. It was not until the Bland enquiry in Victoria[4] that there was an attempt to outline the complex questions in economic theory and practice of determining and measuring road costs and their allocation. In 1978-80 the McDonell Enquiry reviewed road and rail freight transport in New South Wales and its affected cities and regions, (the 'hub' of the Australian freight transport system). It was set up because of the 'truckies' blockades and national disturbances which disrupted access to all mainland capitals. These were largely sparked by the levels of road taxes. This Enquiry developed the first comprehensive theoretical and measurement system for assessing and allocating road costs,.[5][6] This system was subsequently applied more widely,[7] and then extended, with later studies, for the establishment of current national policy and principles.[8][9]

The Federal government provides funds under the AusLink programme for several funding programs including:

- National Projects

- National Network Maintenance, essentially the National Highway, comprising the main freeways and highways linking the major cities of Australia[10]

- Roads to Recovery Program - provides funding allocations to councils in each State or Territory.[11]

- Black Spot Program (improvements to high accident risk spots)[12]

- Strategic Regional Program

- Innovation and Research

- Funding for Local Roads

Other highways and main roads linking regional centres are funded by the respective state governments. Local and minor roads are generally funded by the third tier of government, local councils.

The Business Council of Australia in its Infrastructure Action Plan, estimated that in 2004, road infrastructure was under funded by A$10 billion.[13]

Roads and highways

_Distances_Updated.gif)

Different standards of roads are generally called by various names. With wide variations in population across the nation, the name of a road does not always reflect the construction or capacity of a particular road.

Freeways, motorways, expressways and tollways

Freeways are major roads with more than one lane of traffic in each direction designed for higher speed operation. They have barriers or wide median strips separating traffic travelling in opposite directions, and grade-separated intersections without roundabouts or traffic lights in the main route. Some toll roads are called motorways or tollways to avoid perceived difficulties with charging people to use a freeway. Most Australian capital cities have one or more freeways across, past, or leading to them.

When limited-access highways began to be built in Sydney in the 1950s, beginning with the Cahill Expressway, they were provisionally named expressways, but in the 1960s Australian transport ministers agreed that they be called freeways (like in the United States and other countries). The Cahill Expressway has kept its original name. Melbourne's South Eastern Freeway (now called the 'Monash Freeway') was the second freeway to be opened in Australia, in 1961. However, it was originally only a short road.

Victoria has the most extensive major arterial (freeway) network in the country, including tollways.

Highways

There is an Australian national highway network linking the capital cities of each state and other major cities and towns. The national highway network is PART financed by the Australian Federal Government with the bulk of funding coming from the individual states. Many argue that more needs to be spent on maintenance and upgrading the network..

Each Australian state government maintains their own network of roads connecting most of the towns in the state. Highways and major roads include Metroads, National Routes, State Routes and routes numbered according to the Alphanumeric Route Numbering System.

Some highways in remote areas of Australia are not sealed for high traffic volumes and are not suitable for the whole range of weather conditions. Following heavy rains they may be closed to traffic.

Minor roads

Local governments maintain the vast majority of minor roads in rural areas and streets in towns and suburbs.

Urban

Urban minor roads in Australia are generally sealed, have a 50 km/h speed limit and most are illuminated at night by street lighting.[14]

Rural

Many rural roads are not sealed but are built with a gravel base or simply graded clear and maintained from the available earth.

Outback

Driving on minor outback roads off a sealed road can be dangerous, and motorists are generally advised to take precautions such as:

- seeking local advice

- ensuring that someone is aware of your travel plans

- remaining with vehicle in case of a break-down

- awareness of animals such as kangaroos, especially at night

- travelling with an adequate supply of drinking water

Failure to observe these precautions can result in death.[15]

Ferries

The Spirit of Tasmania is a service operated by TT-Line with two ocean-going ferries providing a "road" link between Tasmania and the mainland. There is also a Searoad ferry service across the opening of Port Phillip connecting Sorrento and Queenscliff. Kangaroo Island is connected to Cape Jervis by the SeaLink service.

Many of the road crossings over the lower Murray River are provided by government-operated cable ferries.

Road rules and regulation

Economic regulation

Although trucks had played important local carriage tasks since their introduction to Australia, it was not until the 1970s that improved highways and larger trucks allowed the rapid development of long haul operations and intense competition with rail transport. This situation led to the industry disturbances (see section Costs and funding above) on the causes of which the Commission of Enquiry into the NSW freight industry reported.[16] The Enquiry made a series of recommendations for reform involving economic principles, legal provisions, financing, economic regulation and safe operating conditions but found that effective action could not be taken at the State level. It would require re-examination of the central issue of freedom of interstate transport as embodied in Section 92 of the Constitution of Australia, and the development of appropriate national responses. With this basis, the National Freight Inquiry,[17][18] completed a comprehensive survey of the national industry with major proposals. This resulted in long running development of new governance arrangements and policy for economic regulation of both road and rail freight transport. As a result, following the cooperative Federalism initiative of the 1990s, these matters are the responsibility of the National Transport Commission,[19] within the general oversight of the Australian Transport Council of Ministers.[20]

Operating regulation

Vehicles in Australia are right-hand drive, and vehicles travel on the left side of the road. The laws for all levels of government, have been mostly harmonised so that drivers do not need to learn different rules as they cross state borders.[21] The usual speed limits are 100 km/h outside of urban areas (110 km/h on some roads where signposted). Major routes in built up areas are 80 km/h and 60 km/h, with streets generally limited to 50 km/h, often not separately signposted. Until the end of 2006, major highways in the Northern Territory had no speed limit, but now the maximum speed there is 130 km/h where signposted on the Stuart, Barkly, Victoria and Arnhem Highways, with a default of 110 km/h on all other rural roads where not otherwise signposted.[22]

Speed limits are enforced with mobile and fixed cameras as well as mobile radar guns operated by police and State Road Authorities such as VicRoads. Heavy transport operators must record their driving time in a log book and take regular rest periods and are limited in how long they can drive without longer sleeping time.

If two roads with two lanes each way meet at a roundabout, the roundabout is marked with two lanes as well. Traffic turning left must use the left lane, and traffic turning right must approach in and use the right lane, travelling clockwise around the island in the centre. Traffic going straight through may generally use either lane. Vehicles must indicate their intended direction when approaching the roundabout, and indicate left when passing the exit before the one they intend to leave on. Vehicles entering the roundabout must give way to vehicles already on it.

Licensing

Typically, the first stage of licensing is gaining a learners permit. The minimum age to get this in most states is 16, and it requires:

- passing a test of knowledge of the road rules

- special L plates to be displayed, typically displaying a black L on a yellow background

- reduced blood alcohol limits compared to unrestricted drivers (acceptable BAC varies by state)

- a fully licensed driver to be in the car with the learner at all times, who must also be under the legal alcohol limit (0.05 BAC in most states)

- some states will impose maximum speeds for learner drivers (for instance, New South Wales learners are limited to 90 km/h)

- There is No requirement for professional training during the Learning or Probationary licensing periods.

After a set period of time (usually between three and twelve months), and often a certain number of hours practice, the learner driver is eligible to apply for their licence. In most states, there's also an age limit (which ranges from 16 ½ to 18, depending on state). In most states, including NSW, QLD, WA, Tas and ACT, the limit is 17. This process typically involves a practical driving test and a computerised test involving a hazard perception section and possibly some multiple choice questions. The first licence is a restricted licence known as a probationary licence or provisional licence, which typically lasts for up to three years. These drivers must display special plates (design differs across states but may be a white P on a red background, or a red or green P on a white background). This has earned them the name P Platers. Some restrictions placed on these drivers include (dependent on state):

- Reduced blood alcohol limits compared to unrestricted drivers (acceptable BAC varies by state).

- Automatic transmission only if licence test taken in an automatic vehicle.

- Limits on power/performance of cars (certain states only).

- Fewer demerit points to be accrued before licence is suspended.

- Speed limitations (certain states only).

Some states have a two-stage probationary licensing system, where the first year of a licence has extra restrictions (and often a different coloured plate) to the later years.

Special licences exist for:

- Cars (which typically enables people to drive a car with up to 12 seats, and up to 4.5 tonnes GVM)

- Light Rigid trucks and buses

- Medium Rigid trucks and buses

- Heavy Rigid trucks

- Heavy Combination trucks

- Multi Combination trucks (B-doubles and road trains)

- Motorcycles

Heavy vehicle class licences require drivers to have experience at lighter licence classes. In some states, a car licence is acceptable for motorcycles with limited engine capacity.

Vehicles

Cars

_SV6_sedan_(2018-10-01)_01.jpg)

Five manufacturers have previously manufactured cars in Australia, all of which ceased local production in or prior to 2017. All were subsidiaries of international companies, but manufactured models designed specifically for the Australian market. They were:

- Ford: Falcon, Laser and Territory

- Holden: Commodore, Statesman/Caprice, Cruze

- Mitsubishi: Colt, Sigma, Magna/Verada, 380

- Nissan: Bluebird, Pulsar, Pintara

- Toyota: Camry, Corolla and Aurion

The distance travelled by car in Australia is amongst the highest in the world, behind the United States and Canada. In 2003, the average distance travelled per person by car was 12,730 km.[1]

Introduction of airbags and ESC into the Australian car market:

Frontal airbags were introduced on Australian market around the 1990s. By 2006, airbag was a standard feature for around 90% of new cars. In 2014, around 80% of the national car fleet had a driver's airbag, and more than 50% a passenger airbag.[23] It is estimated that frontal airbags reduce fatalities by 20% and side airbags by 51%.[23]

Electronic Stability Control(ESC)began to be sold as a standard feature in Australia from 1999. ESC was mandated for all new passenger cars in 2013 and was mandated for all new light commercial vehicles by 2017. It is estimated that around 29 per cent of the light vehicle fleet was equipped with a form of ESC by 2014. It is considered that ESC reduces fatalities by 53% in some crashes.[23]

Trucks

Most long-haul road freight is carried on B-double semi-trailers. These trucks typically have a total of 9 axles and two articulation points . Normal semi- trailers usually have a tri-axle trailer towed by a twin-drive prime mover. In the remote areas of the north and west, three- and four-trailer road trains are used for general freight, fuel, livestock and mineral ores. Two-trailer road trains are allowed closer to populated areas, especially for bulk grain and general freight.

From July 2007, the Federal and State governments approved B-triple trucks that are allowed only to operate on a designated network of roads . A B-Triple is said to carry the load of five semi-trailers. B-Triples are set up differently from conventional road trains. The front of their first trailer is supported by the turntable on the prime mover. The second and third trailers are supported by turntables on the trailers in front of them. As a result, B-Triples are much more stable than road trains and handle exceptionally well.

The largest road transport companies are Toll Holdings and Linfox, but there are many others, including owner-drivers with only their own truck.

Buses

- Main category: Bus transport in Australia

Buses in Australia provide a variety of services, generally in one or more of the following categories:

- route services, following a fixed route and a published timetable, operated by government or private companies

- school services, transporting students to and from school, often under a government-subsidised scheme

- long distance services, providing intrastate and interstate travel between major towns and cities

- tourist services, operating one-day and extended tours to popular destinations

- charter services, offering buses for hire to transport like-minded people to a chosen destination

- shuttle services, providing point-to-point transport, e.g. airport to hotels

- private vehicles, maintained by companies, schools, churches or other organisations to transport their members.

Many aspects of the bus industry are heavily controlled by government. These controls may include age and condition of the bus, driver licensing and working hours, fare structure, routes and frequency of services.

Trams

Trams were used in most Australian cities until the early 1960s. The Melbourne tram system is the largest in the world and remains an integral part of inner city commuting. Their cars intersect with others and large volumes of commuters have ready access to this form of transport. Tram and light rail systems are being reintroduced to some cities, such as the network in Sydney. The only remaining tram route in Adelaide is the Glenelg Tram, which was extended through the CBD in 2007 and again in 2009. At the Gold Coast a thirteen kilometre light rail system opened between Broadbeach and the Gold Coast University Hospital in 2014, and was extended 7 kilometres to Helensvale Railway Station in 2017.

Motorcycles

Motorcycles account for around 3% of vehicles in Australia.[24]

Bicycles

- Main category: Cycling in Australia

In the late-19th and early-20th centuries - the bicycle was used extensively in the outback and countryside of Australia as an economical means of transport. In the urban areas the bicycle found wide usage where workers were living in reasonable proximity to their places of work - this can be seen in the extent of bicycle racks at Midland Railway Workshops for example.

Over a third of the population ride a bike at least once a year and over half of all households have at least one working bicycle.[25] They are used for recreation, exercise and commuting. Most cities have developed bicycle usage strategies, while some, such as Canberra and Perth have extensively promoted bicycle usage and constructed an extensive network of cycleways that can be used by cyclists to travel large distances across the city. The recreational use of bicycles has been supported by local and state governments producing publications and websites that encourage recreational and more lately utility usage. Considerable numbers of tourists and enthusiasts use road and off-road routes that have been marked or signed for bicycle tours. Good examples are the Mawson Trail in South Australia and the Munda Biddi Trail in Western Australia.

Electric vehicles

The adoption of plug-in electric vehicles in Australia is driven by customer demand due to the lack of government policies or monetary incentives to support the adoption and deployment of low or zero emission vehicles.

The total stock of plug-in electric vehicles is almost 12,000 with 6,718 of these electric cars sold in 2019 alone with the other sales occurring between 2012 and 2018.[28][29][30] A further 14,253 electric vehicles were registered in early 2020 which is nearly double the registrations of the previous year.[31] The Mitsubishi Outlander P-HEV was the country's top selling plug-in electric vehicle, with over 2,906 plug-in hybrid SUVs sold through March 2018.[32] However, Tesla accounted for 70% of the 6,718 electric car sales in 2019 with the Tesla Model 3 compromising two-thirds of electric car sales in the year.[33] The electric Tesla Model X and Model 3 are Australia's second and third most safest cars.[34] While the Mercedes-Benz all-electric EQC was named the best car in Australia in 2019.[35]

Victoria is Australia's most important electric vehicle market with the most electric vehicle purchases in Australia between 2011 and 2017 with a total of 1,324 car sales.[36] Victoria is also Australia's most important electric vehicle market because it had the most electric vehicle chargers in the country.[36] Similarly, Victoria's capital city Melbourne, had the highest concentration of electric vehicle chargers in Australia in 2017.[36] Victoria had 403 electric vehicle chargers in 2019 with another 31 expected to be constructed by the end of 2020.[37] Victoria almost doubled the electric vehicle charger network from 216 chargers in 2018 to 403 chargers in 2019.[37][36] Victoria also manufactures electric vehicles with a commercial electric vehicle manufacturing facility to be established in Victoria in 2021, producing 2,400 vehicles per year.[38] The Victorian company SEA Electric also manufactures electric trucks and other vehicles for domestic and international markets.[39][40] Overall, Victoria, Australian Capital Territory/New South Wales, South Australia and Tasmania represent the largest markets in the country for electric car sales.[36]

The 2018 Electric Vehicle Council report Recharging the Economy, stated a high adoption of electric vehicles has the potential to boost GDP by $2.9 billion and support 13,400 jobs by 2030, and has other positive economic effects including lower fuel costs and better fuel security, improved public health and growth of EV supply chains.[41] A study in 2020 by ClimateWorks Australia, stated that at least 50% of all new cars sold in 2030 will need to be electric vehicles to remain within 2C of global warming by 2050.[42] The study further found that Australia will require an accelerated rollout of electric vehicles to transition to net zero emissions by 2050 and to ensure 100% renewable energy by 2035.[42]Safety

Road transport safety in Australia is of a moderate to high standard. In 2018, fatalities is in the mean of the 30 OECD countries.[43] Road quality, safety barriers and other safety features are of a moderate level in urban areas and of a high standard on new roads; however in regional areas and on some major highways, road quality can be severely affected by lack of funding for maintenance. Speed is limited to around 100 km/h on most highways.

In 2019, the number of people killed on Australian roads is estimated at 1,188 travelers that is 4.7% more than on 2018. This makes 4.7 travelers killed per 100,000 population[44]

Vehicles are moderately safe. Many vehicle users cannot afford newer vehicles and as a result, the second-hand car market is quite large. There are many older model vehicles and while they require a Road Worthy Certificate (RWC) to ensure basic operation is sound, only newer vehicles have safety features such as crumple zones, air bags, etc. Seat belt usage is very high and it is illegal to not wear a seatbelt.

Several efforts have been made at educating the mass population about road safety, the most prominent and successful being the Victorian state Transport Accident Commission (TAC) road safety advertisements, which began in the late-1980s in print and television, which often depicted horrific and graphic road accidents initiated by various causes such as speed, alcohol and drug use, distraction, fatigue and many others. The TAC ads were very effective and reduced the road toll drastically. The method was subsequently adopted elsewhere in Australia and around the world.

Speed limits have been progressively reduced in urban streets, from 60 km/h to 50 km/h and more recently, to 40 km/h near schools, in built up areas and shopping strips. This is to ensure safer stopping distances to minimise/reduce pedestrian injuries and casualties.

Safety varies between remoteness area, from a rate of 2.64 in major cities in 2016, to a rate of 34.58 in remote areas[45]

In 1992, first National Road Safety Strategy was established by federal, state and territory transport Ministers.[46]

The 2001–2010 australian safe-system strategy, achieved a fatality reduction rate of 34% for a reduction target of 40%.[46]

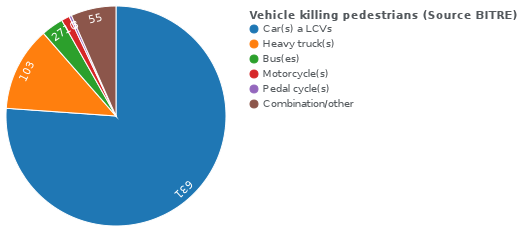

Pedestrian safety

75.8% of fatal pedestrian crashes involved passenger cars or light commercial vehicles, between 2009 and 2013.[47]

Pedestrians older than 75 have the highest pedestrian fatality rate of any age group.[47]

Fatality risk

An Australian study of the risk of deaths once the accident occurred found various possible factors.[48] This study concludes that the risk of death is higher in rural area.

This study use the notion of odds ratio:

| Risk factor | Odd ratio | Risk factor (%) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rural (vs Urban) | 1.91 | 91% | higher risk in rural zone than in urban zone |

| Sex (Male vs Woman) | 1.28 | 28% | higher risk for a male than a female |

| driver no restraint | 12.02 | higher risk for without restraint driver than a driver with restraint | |

| passenger no restraint | 13.02 | higher risk for without restraint passenger than a driver with restraint | |

| 70 km/h (vs 60 km/h) | 1.25 | 25% | risk of being killed is 25% higher at 70 km/h speed limit rather than at 60 km/h speed limit |

| Manufacture date | 0.82 | -18% | A car built in 2010 is safer than a car build on 2000 |

Road naming

Each state has independent systems for the naming of roads. Roads in New South Wales are named in accordance with section 162 of The Roads Act 1993. Australian Standards AS 1742.5 - 1986 and AS 4212 - 1994 provide a list of road suffixes (such as Alley, Circle, Mall, Street) which are routinely accepted by the Geographical Names Board.[49]

Authorities

The Australian commonwealth government has had a number of statutory authorities relative to roads including: -

- Australian Transport Council

- National Transport Commission

State governments have been co-ordinated through: -

- Austroads (formerly the National Association of Australian State Road Authorities).

In Victoria the state road authority is the Roads Corporation better known as VicRoads and in New South Wales it is known as the Roads and Maritime Services (RMS).

See also

- Road transport in Victoria

References

- "Transport in Australia". International Transport Statistics Database. iRAP. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- "Where are we now?". Australian Automobile Association. Archived from the original on 22 February 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- The tyranny of distance : how distance shaped Australia's history / Geoffrey Blainey | National Library of Australia. Catalogue.nla.gov.au. 2001. ISBN 9780732911171. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- Sir Henry Bland, Reports of the Board of Inquiry into Victorian land transport, Government of Victoria, 1972

- "Penrith City Library". Opac.penrithcity.nsw.gov.au. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- "Transport Reviews: A Transnational Transdisciplinary Journal". 8 (2). 1988. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Laird, P. G. (1985). "Transport '85: Preprints of Papers - Road Freight Deficits (Engineering Collection) - Informit". Transport '85: Preprints of Papers. Search.informit.com.au: 26. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- "AN OVERVIEW OF THE AUSTRALIAN ROAD FREIGHT TRANSPORT INDUSTRY" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- "Back on Track: Rethinking Transport Policy in Australia and New Zealand". Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- "National Projects". Australian Government Department of Transport and Regional Services. Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- "Roads to Recovery Program Funding Allocations". Australian Government Department of Transport and Regional Services. Archived from the original on 24 June 2007. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- "Black Spot Program". Nationbuildingprogram.gov.au. 23 September 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- "Infrastructure to sustain growth (PDF linked)". Business Council of Australia. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- "Minor Roads Lighting Solutions". Philips Electronics. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- "Australian Outback Survival". Outback Australia Travel Guide. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- McDonell, G. J. (1981). "Transportation Conference 1981: Preprints of Papers - Road/Rail Rationalisation, Transport Regulation, and Section 92: Findings of the Commission of Enquiry into the NSW Freight Transport Industry (Engineering Collection) - Informit". Transportation Conference 1981: Preprints of Papers. Search.informit.com.au: 87. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- National Road Freight Industry Inquiry report, September 1984 / Thomas E. May, chairman ; Gordon Mil... | National Library of Australia. Catalogue.nla.gov.au. 1984. ISBN 9780644035644. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- "Overview of Australian Road Freight Industry:Submission to National Inquiry 1983" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- "National Transport Commission". NTC. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 February 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Australian Road Rules". South Australian Department for Transport Energy and Infrastructure. Archived from the original on 27 December 2002. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- "Changes to road rules on 1 January 2007". Government of the Northern Territory. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- "data" (PDF). bitre.gov.au. 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Motorcycle Use in Victoria". Parliament of Victoria. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- "Australian Cycling Participation 2013". Austroads. 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- Schmidt, Bridie (30 August 2019). "First Tesla Model 3 electric sedans delivered to customers in Australia". RenewEconomy. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Charlwood, Sam (31 May 2019). "Tesla Model 3 Australian pricing revealed". Carsales. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- Schmidt, Bridie (6 March 2020). "Tesla claims 80% of Australian market as electric vehicles near 18,000 mark". The Driven. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- Latimer, Cole (27 November 2018). "Electric cars continue push into Australia despite lack of government support". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- Harris, Rob (5 February 2020). "Sharp jump in electric vehicle sales underscores 'untapped potential'". The Age. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (29 May 2020). "Media Release - Electric vehicle registrations almost double (Media Release)". www.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "New (MY19) Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV - Summer 2018" (PDF) (Press release). Mitsubishi Motors. 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2018. See tables in pp. 3-4.

- "Tesla takes 70 per cent of market, as Australia electric car sales reach 5,000 in 2019". The Driven. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "Tesla Models X and 3 ranked among Australia's Top 3 safest cars for 2019". The Driven. 20 December 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Schmidt, Bridie (31 January 2020). "Mercedes Benz electric car beats Model 3 to win top Australia car award". The Driven. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "The State of Electric vehicles in Australia - Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA)". Australian Renewable Energy Agency. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Topsfield, Jewel (26 December 2019). "Victoria rolls out electric car charging stations to tackle 'range anxiety'". The Age. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Energy (17 December 2019). "Zero emissions vehicles". Energy. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Australia's SEA Electric takes massive order for 100 electric trucks". The Driven. 15 November 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Australia's SEA Electric is set to displace diesel in commercial vehicles worldwide". pv magazine Australia. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "NSW flags imminent release of EV strategy, as feds ignore electric in auto transition report". The Driven. 17 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- editor, Katharine Murphy Political (26 February 2020). "Australia's electricity market must be 100% renewables by 2035 to achieve net zero by 2050 - study". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 February 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "International Road Safety Comparisons—Annual". 20 September 2018.

- https://www.bitre.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/rda_dec_2019.pdf

- "Info" (PDF). bitre.gov.au. 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Road safety in Australia".

- "data" (PDF). bitre.gov.au. 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Data" (PDF). bitre.gov.au. 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Guidelines for the Naming of Roads" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2006. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

Further reading

- Documents, Australian Transport Council

- Fitzpatrick, Jim (1980). The bicycle and the bush: man and machine in rural Australia. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554231-2.

- Hemmings, Leigh (1991). Bicycle touring in Australia. East Roseville, N.S.W.: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7318-0197-0.

- National Association of Australian State Road Authorities (1987) Bush track to highway : 200 years of Australian roads Sydney. ISBN 0-85588-207-7

- Veith, Gary (1999). Guide to traffic engineering practice. Part 14, Bicycles. Austroads. ISBN 0-85588-438-X.