Srinagar

Srinagar (/ˈsriːnəɡər/ (![]()

Srinagar | |

|---|---|

From the top clockwise: Panorama of Srinagar City, Dal Lake, Pari Mahal, Tulips at Indira Gandhi Memorial Tulip Garden, Jamia Masjid, Srinagar, Hazratbal shrine | |

| Coordinates: 34°5′24″N 74°47′24″E | |

| Country | |

| Union Territory | Jammu and Kashmir |

| District | Srinagar |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Vacant |

| Area | |

| • City | 294 km2 (114 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,585 m (5,200 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • City | 1,180,570 |

| • Rank | 34th |

| • Density | 4,000/km2 (10,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,273,312[2] |

| • Metro Rank | 38th |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Urdu[3] |

| • Other Spoken languages | Kashmiri |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 190001 |

| Telephone code | 0194 |

| Vehicle registration | JK 01 |

| Sex ratio | 888 ♀/ 1000 ♂ |

| Literacy | 69.15% |

| Distance from Delhi | 876 kilometres (544 mi) NW |

| Distance from Mumbai | 2,275 kilometres (1,414 mi) NE (land) |

| Climate | Cfa |

| Precipitation | 710 millimetres (28 in) |

| Avg. summer temperature | 23.3 °C (73.9 °F) |

| Avg. winter temperature | 3.2 °C (37.8 °F) |

| Website | www |

Origin of name

The earliest records, such as Kalhana's Rajatarangini, the name Siri-nagar (or Sri-nagara) is mentioned, which in turn is a local transformation of the Sanskrit name Sūrya-nagar, meaning "City of the Sun".[7] The name Sri-nagar is also used in the records of the Chinese Tang Dynasty.

Alternatively, it may have drawn its name from two Sanskrit words: śrī (venerable), and nagar (city), which would make it the "City of Wealth".

History

Ancient period

The Burzahom archaeological site 10 km from Srinagar has revealed the presence of neolithic and megalithic cultures.[8]

According to Kalhana's 12th century text Rajatarangini, a king named Pravarasena II established a new capital named Pravarapura (also known as Pravarasena-pura). Based on topographical details, Pravarapura appears to be same as the modern city of Srinagar. Aurel Stein dates the king to 6th century.[9]

Kalhana mentions that a king named Ashoka (Gonandiya) had earlier established a town called Srinagari. Kalhana describes this town in hyperbolic terms, stating that it had "9,600,000 houses resplendent with wealth".[10] According to Kalhana, this Ashoka reigned before 1182 BCE and was a member of the dynasty founded by Godhara. Kalhana states that this king adopted the doctrine of Jina, constructed stupas and Shiva temples, and appeased Bhutesha (Shiva) to obtain his son Jalauka.

Multiple scholars identify Kalhana's Ashoka with the 3rd century Buddhist Mauryan emperor Ashoka despite these discrepancies.[11] Although "Jina" is a term generally associated with Jainism, some ancient sources use it to refer to the Buddha.[10] Romila Thapar equates Jalauka to Kunala, stating that "Jalauka" is an erroneous spelling caused by a typographical error in Brahmi script.[11]:130

Ashoka's Srinagari is generally identified with Pandrethan (near present-day Srinagar), although there is an alternative identification with a place on the banks of the Lidder River.[12] According to Kalhana, Pravarasena II resided at Puranadhishthana ("old town") before the establishment of Pravarapura; the name Pandrethan is believed to be derived from that word.[9][13] Accordining to V. A. Smith, the original name of the "old town" (Srinagari) was transferred to the new town.[14]

Srinagar in 14th to 19th centuries

The independent Hindu and Buddhist rule of Srinagar lasted until the 14th century when the Kashmir valley, including the city, came under the control of the first of several Muslim rulers, including the Mughals. It was also the capital during the reign of Yusuf Shah Chak. Kashmir came under Mughal rule, when it was conquered by the third Mughal badshah (emperor) Akbar in 1586 CE. Akbar established Mughal rule in Srinagar and Kashmir valley.[15] Kashmir was added to Kabul Subah in 1586, until Shah Jahan made it into a separate Kashmir Subah (imperial top-level province) with seat in Srinagar.

With the disintegration of the Mughal empire after the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, infiltration in the valley of the Afghan tribes from Afghanistan and Hindu Dogras from the Jammu region increased, and the Afghan Durrani Empire and Dogras ruled the city for several decades.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the Sikh ruler from the Punjab region annexed a major part of the Kashmir Valley, including Srinagar, to his kingdom in the year 1814 and the city came under the influence of the Sikhs.

In 1846, the Treaty of Lahore was signed between the Sikh rulers and the British in Lahore. The treaty inter alia provided British de facto suzerainty over the Kashmir Valley and Maharaja Gulab Singh, a Hindu Dogra from the Jammu region became a semi-independent ruler of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Srinagar became part of his kingdom and remained until 1947 as one of several princely states in British India. The Maharajas choose Sher Garhi Palace as their main Srinagar residence.

Post independence

After India and Pakistan's independence from Britain, villagers around the city of Poonch began an armed protest at the continued rule of Maharaja Hari Singh on 17 August 1947.[16] In view of the Poonch uprising, certain Pashtun tribes such as the Mehsuds and Afridis from the mountainous region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in Pakistan, with the backing of the Pakistani government, entered the Kashmir valley to capture it on 22 October 1947.[17] The Maharaja, who had refused to accede to either India or Pakistan in hopes of securing his own independent state, signed the Instrument of Accession to India in exchange for refuge on 26 October 1947, as Pakistani-backed tribesmen approached the outskirts of Srinagar. The accession was accepted by India the next day. The government of India immediately airlifted Indian Army troops to Srinagar, who engaged the tribesmen and prevented them from reaching the city.[18]

In 1989, Srinagar became the focus of the insurgency against Indian rule. The area continues to be a highly politicised hotbed of separatist activity with frequent spontaneous protests and strikes ("bandhs" in local parlance). On 19 January 1990, the Gawakadal massacre of at least 50 unarmed protestors by Indian forces, and up to 280 by some estimates from eyewitness accounts, set the stage for bomb blasts, shootouts, and curfews that characterised Srinagar throughout the early and mid-1990s.[19][20] Further massacres in the spring of 1990 in which 51 allegedly unarmed protesters were allegedly killed by Indian security forces in Zakura and Tengpora heightened anti-Indian sentiments in Srinagar.[21] As a result, bunkers and checkpoints are found throughout the city, although their numbers have come down in the past few years as militancy has declined. However, frequent protests still occur against Indian rule, such as the 22 August 2008 rally in which hundreds of thousands of Kashmiri civilians protested against Indian rule in Srinagar.[22][23][24] Similar protests took place every summer for the next 4 years. In 2010 alone 120 protesters, many of whom were stone pelters and arsonists, were killed by police and CRPF. Large scale protests were seen following the execution of Afzal Guru in February 2013.[25] In 2016, after the death of militant leader Burhan Wani, there were mass protests in the valley and about 87 protesters were killed by Indian Army, CRPF and police in the 2016 Kashmir unrest.

The city also saw increased violence against minorities, particularly the Hindu Kashmiri Pandits, starting from mid-1980s and resulting in their ultimate exodus.[26][27][28] Posters were pasted to walls of houses of Pandits, telling them to leave or die, temples were destroyed and houses burnt;[29] but a very small minority of pandits still remains in the city.[30] The recent years have seen protests in Srinagar from local Kashmiri pandits for protection of their shrines in Kashmir and their rights.[31]

After revocation of the special status of Jammu and Kashmir and the subsequent devolution of the state into a union territory in August 2019, a lockdown was imposed in Kashmir, including in Srinagar.[32] This lockdown has been ongoing for over a year. Thousands, including two former chief ministers, were arrested during this lockdown.[33]

Geography

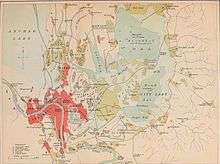

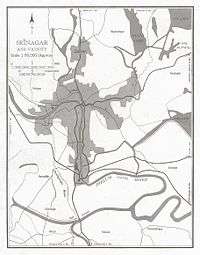

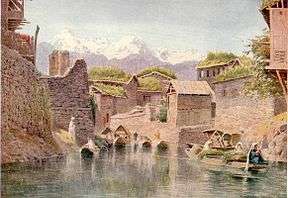

The city is located on both the sides of the Jhelum River, which is called Vyath in Kashmir. The river passes through the city and meanders through the valley, moving onward and deepening in the Wular Lake. The city is known for its nine old bridges, connecting the two parts of the city.

There are a number of lakes and swamps in and around the city. These include the Dal, the Nigeen, the Anchar, Khushal Sar, Gil Sar and Hokersar.

Hokersar is a wetland situated near Srinagar. Thousands of migratory birds come to Hokersar from Siberia and other regions in the winter season. Migratory birds from Siberia and Central Asia use wetlands in Kashmir as their transitory camps between September and October and again around spring. These wetlands play a vital role in sustaining a large population of wintering, staging and breeding birds.

Hokersar is 14 km (8.7 mi) north of Srinagar, and is a world class wetland spread over 13.75 km2 (5.31 sq mi) including lake and marshy area. It is the most accessible and well-known of Kashmir's wetlands which include Hygam, Shalibug and Mirgund. A record number of migratory birds have visited Hokersar in recent years.[34]

Birds found in Hokersar are migratory ducks and geese which include brahminy duck, tufted duck, gadwall, garganey, greylag goose, mallard, common merganser, northern pintail, common pochard, ferruginous pochard, red-crested pochard, ruddy shelduck, northern shoveller, common teal, and Eurasian wigeon.

Climate

Srinagar has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa). The valley is surrounded by the Himalayas on all sides. Winters are cool, with daytime temperature averaging to 2.5 °C (36.5 °F), and drops below freezing point at night. Moderate to heavy snowfall occurs in winter and the highway connecting Srinagar with the rest of India faces frequent blockades due to icy roads and avalanches. Summers are warm with a July daytime average of 24.1 °C (75.4 °F). The average annual rainfall is around 720 millimetres (28 in). Spring is the wettest season while autumn is the driest. The highest temperature reliably recorded is 39.5 °C (103.1 °F) and the lowest is −20.0 °C (−4.0 °F).[35]

| Climate data for Srinagar (1981–2010 normals, extremes 1901–2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

27.3 (81.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

36.4 (97.5) |

37.8 (100.0) |

39.5 (103.1) |

36.7 (98.1) |

35.0 (95.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

39.5 (103.1) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 11.6 (52.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

30.4 (86.7) |

33.8 (92.8) |

34.2 (93.6) |

33.3 (91.9) |

31.5 (88.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

34.8 (94.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.7 (44.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

20.4 (68.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.7 (85.5) |

29.5 (85.1) |

27.6 (81.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

16.0 (60.8) |

9.5 (49.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

5.1 (41.2) |

9.5 (49.1) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.8 (64.0) |

21.6 (70.9) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.5 (74.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

8.2 (46.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.9 (28.6) |

0.4 (32.7) |

4.1 (39.4) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.0 (51.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

12.6 (54.7) |

5.9 (42.6) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −5.7 (21.7) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.5 (50.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −14.4 (6.1) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.3 (50.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 53.9 (2.12) |

81.9 (3.22) |

117.6 (4.63) |

90.8 (3.57) |

71.0 (2.80) |

42.0 (1.65) |

68.9 (2.71) |

64.2 (2.53) |

29.0 (1.14) |

27.8 (1.09) |

28.7 (1.13) |

46.0 (1.81) |

721.8 (28.42) |

| Average rainy days | 4.9 | 5.9 | 7.9 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 3.9 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 56.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 69 | 62 | 54 | 49 | 50 | 46 | 54 | 56 | 51 | 54 | 61 | 70 | 56 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 74.4 | 101.7 | 136.4 | 189.0 | 238.7 | 246.0 | 241.8 | 226.3 | 228.0 | 226.3 | 186.0 | 108.5 | 2,203.1 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 2.4 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 6.3 | 7.7 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 7.3 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 6.2 | 3.5 | 6.0 |

| Source 1: India Meteorological Department[36][35] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun 1945–1988),[37] Tokyo Climate Center (mean temperatures 1981–2010)[38] | |||||||||||||

Economy

In November 2011, the City Mayors Foundation – an advocacy think tank – announced that Srinagar was the 92nd fastest growing urban areas in the world in terms of economic growth, based on actual data from 2006 onwards and projections to 2020.[39]

Tourism

Srinagar is one of several places that have been called the "Venice of the East".[40][41][42] Lakes around the city include Dal Lake – noted for its houseboats – and Nigeen Lake. Apart from Dal Lake and Nigeen Lake, Wular Lake and Manasbal Lake both lie to the north of Srinagar. Wular Lake is one of the largest fresh water lakes in Asia.

Srinagar has some Mughal gardens, forming a part of those laid by the Mughal emperors across the Indian subcontinent. Those of Srinagar and its close vicinity include Chashma Shahi (the royal fountains); Pari Mahal (the palace of the fairies); Nishat Bagh (the garden of spring); Shalimar Bagh; the Naseem Bagh.[43] Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Botanical Garden is a botanical garden in the city, set up in 1969.[44] The Indian government has included these gardens under "Mughal Gardens of Jammu and Kashmir" in the tentative list for sites to be included in world Heritage sites.

The Sher Garhi Palace houses administrative buildings from the state government. Another palace of the Maharajas, the Gulab Bhavan, has now become the Lalit Grand Palace hotel.[45]

The Shankaracharya Temple which lies on a hill top in the middle of the city, besides the Kheer Bhawani Temple are important Hindu temples in the city.[46]

The floating vegetable market on Dal Lake, the only one of its kind in India

The floating vegetable market on Dal Lake, the only one of its kind in India

The Houseboats of Dal Lake

The Houseboats of Dal Lake Scenic View of Wular Lake

Scenic View of Wular Lake Beautiful Nishar Bagh Mughal Gardens and its twelve descending terraces of water and flowers.

Beautiful Nishar Bagh Mughal Gardens and its twelve descending terraces of water and flowers. Manasbal Lake

Manasbal Lake Chashme Shahi (Mughal Garden) Kashmir

Chashme Shahi (Mughal Garden) Kashmir Shalimar Gardens

Shalimar Gardens Bot garden lake

Bot garden lake.jpg) Hari Parbat Fort

Hari Parbat Fort Pari Mahal - Group of arched terraces / structural complex in Srinagar

Pari Mahal - Group of arched terraces / structural complex in Srinagar

Government and politics

The city is run by the Srinagar Municipal Corporation (SMC) under leadership of Mayor. The Srinagar district along with the adjoining Budgam and Ganderbal districts forms the Srinagar Parliamentary seat.

Stray dog controversy

Srinagar's city government attracted brief international attention in March 2008 when it announced a mass poisoning program aimed at eliminating the city's population of stray dogs.[47] Officials estimate that 100,000 stray dogs roam the streets of the city, which has a human population of just under 900,000. In a survey conducted by an NGO, it was found that some residents welcomed this program, saying the city was overrun by dogs, while critics contended that more humane methods should be used to deal with the animals.

The situation has become alarming with local news reports coming up at frequent intervals highlighting people, especially children being mauled by street dogs.[48]

Demographics

As of 2011 census Srinagar urban agglomeration had 1,273,312 population.[6] Both the city and the urban agglomeration has average literacy rate of approximately 70%.[6][50] The child population of both the city and the urban agglomeration is approximately 12% of the total population.[6] Males constituted 53.0% and females 47% of the population. The sex ratio in the city area is 888 females per 1000 males, whereas in the urban agglomeration it is 880 per 1,000.[6][51] The predominant religion of Srinagar is Islam with 96% of the population being Muslim. Hindus constitute the second largest religious group representing 2.75% of the population. The remaining population constitutes Sikhs, Buddhist and Jains.[52]

Transport

Road

The city is served by many highways, including National Highway 1A and National Highway 1D.[53]

Air

Srinagar International Airport has regular domestic flights to Leh, Jammu, Chandigarh, Delhi and Mumbai and occasional international flights. An expanded terminal capable of handling both domestic and international flights was inaugurated on 14 February 2009 with Air India Express flights to Dubai. Hajj flights also operate from this airport to Saudi Arabia.[54]

Rail

Srinagar is a station on the 119 km (74 mi) long Banihal-Baramulla line that started in October 2009 and connects Baramulla to Srinagar, Anantnag and Qazigund. The railway track also connects to Banihal across the Pir Panjal mountains through a newly constructed 11 km long Banihal tunnel, and subsequently to the Indian railway network after a few years. It takes approximately 9 minutes and 30 seconds for a train to cross the tunnel. It is the longest rail tunnel in India. This railway system, proposed in 2001, is not expected to connect the Indian railway network until 2017 at the earliest, with a cost overrun of 55 billion INR.[55] The train also runs during heavy snow.

There are proposals to develop a metro system in the city.[56] The feasibility report for the Srinagar Metro is planned to be carried out by Delhi Metro Rail Corporation.[57]

Cable car

Srinagar Cable Car | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In December 2013, the 594m cable car allowing people to travel to the shrine of the Sufi saint Hamza Makhdoom on Hari Parbat was unveiled. The project is run by the Jammu and Kashmir Cable Car Corporation (JKCCC), and has been envisioned for 25 years. An investment of 300 million INR was made, and it is the second cable car in Kashmir after the Gulmarg Gondola.[58]

Culture

Like the state of Jammu and Kashmir, Srinagar too has a distinctive blend of cultural heritage. Holy places in and around the city depict the historical cultural and religious diversity of the city as well as the Kashmir valley.

Places of worship

There are many religious holy places in Srinagar. They include:

- Hazratbal Shrine, only domed mosque in the city.[60]

- Jama Masjid, Srinagar, one of the oldest mosques in Kashmir

- Khanqah-e-Moula, first Islamic centre in Kashmir

- Aali Masjid, in Eidgah Locality

- Hari Parbat hill hosts shrine of Sharika Mata temple

- Zeashta Devi Shrine a holy shrine for Kashmiri Hindus

- Shankaracharya temple

- Kheer Bhawani Temple

- Gurdwara Chatti Patshahi, located on Hari Parbat

- Pathar Masjid

- All Saints Church, Srinagar

- Holy Family Catholic Church (Srinagar)

Additional structures include the Dastgeer Sahib shrine, Mazar-e-Shuhada, Roza Bal shrine, Khanqah of Shah Hamadan, Pathar Masjid ("The Stone Mosque"), Hamza Makhdoom shrine, tomb of the mother of Zain-ul-abidin, tomb of Pir Haji Muhammad, Akhun Mulla Shah Mosque, cemetery of Baha-ud-din Sahib, tomb and Madin Sahib Mosque at Zadibal.[61]

The Sheikh Bagh Cemetery is a Christian cemetery located in Srinagar that dates from the British colonial era. The oldest grave in the cemetery is that of a British colonel from the 9th Lancers of 1850 and the cemetery is valued for the variety of persons buried there which provides an insight into the perils faced by British colonisers in India.[62] It was damaged by floods in 2014.[63] It contains a number of war graves.[64] The notable interments here are Robert Thorpe[65] and Jim Borst.

Hazratbal Shrine built in around 1700 AD

Hazratbal Shrine built in around 1700 AD The Shankaracharya temple built in around 200 BC

The Shankaracharya temple built in around 200 BC Shiv Lingam in a temple in Zaethyar, Srinagar

Shiv Lingam in a temple in Zaethyar, Srinagar Pathar Masjid

Pathar Masjid A view from Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Botanical Garden

A view from Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Botanical Garden

Performing arts

Education

Srinagar is home to The National Institute of Technology Srinagar, formerly known as Regional Engineering College (REC Srinagar). It is one of the oldest among the National Institutes of Technology that were established during the second Five year plan. Other educational institutions are:

Schools

- Tyndale Biscoe School

- Presentation Convent Higher Secondary School

- Burn Hall School

- Mallinson Girls School

- Delhi Public School, Srinagar

- Woodlands House School

- Saint Solomon High School

- Little Angels High School, Srinagar

- Modern High School, Solina, Srinagar

- Green Valley Educational Institute

- RP School Mallabagh

- Crescent Public School

Medical colleges

- Government Medical College, Srinagar

- SMHS Hospital

- Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences

- Government Dental College & Hospital, Srinagar

- Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences and Technology

Universities

- University of Kashmir

- Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Kashmir

- Central University of Kashmir

General degree colleges

Broadcasting

Srinagar is broadcasting hub for radio channels in UT which are Radio Mirchi 98.3FM[66], Red FM 93.5[67] and AIR Srinagar. State television channel DD Kashir is also broadcast.[68]

Sports

The city is home to the Sher-i-Kashmir Stadium, where international cricket matches have been played.[69] The first international match was played in 1983 in which West Indies defeated India and the last international match was played in 1986 in which Australia defeated India by six wickets. Since then no international matches have been played in the stadium due to the security situation (although the situation has now improved quite considerably). Srinagar has an outdoor stadium namely Bakshi Stadium for hosting football matches.[70] It is named after Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad. The city has a golf course named Royal Springs Golf Course, Srinagar located on the banks of Dal lake, which is considered as one of the best golf courses of India.[71] Football is also followed by the youth of Srinagar and Polo ground is maintained for the particular sports recently. There are certain other sports being played but those are away from the main city like in Pahalgam (Water rafting), Gulmarg (skiing).

See also

References

- "Srinagar Municipal Corporation Demographics 2011". 2011 Census of India. Government of India. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- "2011 census of India" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- "Kashmiri: A language of India". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- "Here's how beautiful Srinagar's Dal Lake looks this winter". India Today. 5 January 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "District Srinagar :: Official Website". srinagar.nic.in. Archived from the original on 4 February 2006. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "Jammu and Kashmir Population Census data 2011". 2011 census of India. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- M. Monier Monier–Williams, "Śrīnagar", in: The Great Sanskrit–English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1899

- A. R. Sankhyan (12 March 2008). "Surgery in Ancient India". In Helaine Selin (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 2060. Bibcode:2008ehst.book.....S. ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- M. A. Stein (1989). Kalhana's Rajatarangini: a chronicle of the kings of Kasmir. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 439–441. ISBN 978-81-208-0370-1.

- Nayanjot Lahiri (2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. pp. 378–380. ISBN 978-0-674-91525-1.

- Ananda Guruge (1994). "King Aśoka and Buddhism: historical and literary studies". In Nuradha Seneviratna (ed.). King Asoka and Buddhism: Historical and Literary Studies. Buddhist Publication Society. pp. 185–186. ISBN 978-955-24-0065-0.

- Vincent Arthur Smith (1998). Asoka, the Buddhist Emperor of India. Asian Educational Services. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-81-206-1303-4.

- Mohammad Ishaq Khan (1978). History of Srinagar, 1846-1947: A Study in Socio-cultural Change. Aamir Publications.

- Vincent A. Smith (1999). The Early History of India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 162. ISBN 978-81-7156-618-1.

- "Profile of Srinagar". Indian Heritages Cities Network. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- Umar, Baba (28 February 2013). "'Nehru didn't want to publicise the Poonch rebellion because it would have strengthened Pakistan's case'". Tehelka. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- The Story of Kashmir Affairs – A Peep into the Past Archived 18 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Indo-Pakistan War of 1947". Peace Kashmir. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- Peerzada, Ashiq (27 December 2012). "'90 Srinagar massacre: SHRC orders fresh probe". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

At least 52 people were allegedly killed in security forces' firing during a protest demonstration on January 21, 1990 near Gow Kadal, in heart of Srinagar.

- Dalrymple, William. Kashmir: The Scarred and the Beautiful Archived 30 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. "The New York Review of Books." 1 May 2008.

- "Kashmir marks anniversary of Gaw Kadal Massacre in 1990". Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- "Muslims wage huge Kashmir protest". Chicago Tribune. 23 August 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

A Kashmiri Muslim watches a protest march Friday by hundreds of thousands of Muslims in Srinagar, Indian Kashmir's main city. It was the largest protest against Indian rule in the Himalayan region in more than a decade

- "Hundreds of Thousands March for Kashmir's Independence". The Epoch Times. 22 August 2008. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

Waving green Islamic flags and shouting "we want freedom", hundreds of thousands of Muslims marched peacefully in Indian Kashmir's main city on Friday

- "Muslims in huge Kashmir protest". BBC. 22 August 2008. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

Hundreds of thousands of Muslims have taken part in a protest rally called by separatist leaders in Indian-controlled Kashmir's main city, Srinagar.

- Hussein, AijazSt (12 February 2013). "India's hanging of Kashmiri man leads to fears of new unrest after 2 years of quiet". Star Tribune. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

In all three years, hundreds of thousands of young men took to the streets, hurling rocks and abuse at Indian forces.

- "Paradise Lost". bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- "Violence against Kashmiri hindus". kashmirforum.org. Archived from the original on 13 October 2014.

- "19/01/90: When Kashmiri Pandits fled Islamic terrorists". rediff.com. 19 January 2005. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Kashmiri Pandits offered three choices by Islamists". indiandefencereview.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- "Kashmiri Pandits: Why we never fled Kashmir". aljazeera.com. 2 August 2011. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Kashmiri Pandits stage protest march in Srinagar". The Hindu. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Kashmir city on lockdown after calls for protest march". The Guardian. 23 August 2019.

- "At Least 2,300 People Have Been Detained During the Lockdown in Kashmir". Time. 21 August 2019.

- Ahmed Ali Fayyaz (9 November 2013). "Migratory birds flock avian paradise". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M79. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- "Station: Srinagar Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 721–722. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- "Klimatafel von Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir / Indische Union" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- "Normals Data: Srinagar - India Latitude: 34.08°N Longitude: 74.83°E Height: 1585 (m)". Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- "Srinagar among 100 fastest growing cities in world". Greater Kashmir.com. 17 November 2011. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- "The Sydney Morning Herald - Google News Archive Search". google.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Holloway, James (13 June 1965). "Fabled Kashmir: An Emerald Set Among Pearls". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- The Earthtimes (24 September 2007). "Can Kashmir become 'Venice of the East' again? | Earth Times News". Earthtimes.org. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- "KashmirTreks". kashmirtreks.in. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- "Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Botanical Garden". discoveredindia.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- Saxton, Aditi (25 August 2011). "One hundred years of splendour". India Today. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- "Shankaracharya Temple". jktdc.in. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014.

- "Indian authorities to poison 100K stray dogs - World news - South and Central Asia - NBC News". NBC News. Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- "Stray dogs maul over 3 dozen". Greater Kashmir. 12 May 2012. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- "Census of India 2011 (DCHB-Srinagar)" (pdf). censusindia.gov.in. Census of India. p. 51.

- "Literacy in India". 2011 census of India. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- "Sex Ratio of India". 2011 census of India. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "2011 Census demographics of Srinagar". Archived from the original on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- "Road Map with National Highways of India". Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- "Srinagar International Airport". Airports Authority of India. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014.

- "Kashmir rail by 2017-end, cost overrun Rs 5,500 cr". The Hindu Business Line. 6 December 2012. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- "Now, metro set to roll into Kashmir". Indian Express. 5 August 2013. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- Hassan, Ishfaq-ul (12 February 2010). "Omar Abdullah plans metro in Jammu, Srinagar". DNA. Archived from the original on 30 October 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

“We will soon have the feasibility of metro services in both cities analysed by experts. Ideally, we would like DMRC to send a team and prepare a project report,” minister for urban development Nasir Aslam Wani said.

- "Kashmir gets a dream ropeway". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 24 December 2013. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- Raina, Muzaffar (7 May 2012). "Boat down the Jhelum". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- "Hazratbal Shrine". travelinos.com. 2013. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- "Chapter 4 of Ancient Monuments of Kashmir by Ram Chandra Kak (1933)". Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Brigid Keenan (20 May 2013). Travels in Kashmir. Hachette India. ISBN 978-93-5009-729-8.

- Flood ravages Srinagar’s British-era buildings. Archived 27 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine Noor-Ul-Qamrain, The Sunday Guardian, 27 September 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Karachi 1914-1918 War Memorial. Archived 21 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Grave of Kashmir's first known martryr lies beneath rubble after floods. Swati Bhasin, DNA of Srinagar, 10 October 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/mirchi-98-3-starts-operations-in-srinagar/articleshow/64630395.cms

- http://www.uniindia.com/~/eid-ul-azha-red-fm-launches-station-in-srinagar/India/news/1326138.html

- https://www.hindustantimes.com/chandigarh/j-k-govt-starts-tele-classes-for-valley-students/story-TPEti3YV33R44IlhArCWuO.html

- "Records / Sher-i-Kashmir Stadium, Srinagar / One-Day Internationals". ESPNCricinfo. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "J&K stadium hosts football match after 25-year gap". Times of India. 16 July 2012. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "India". Robert Trent Jones – Golf Architects. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

Bibliography

- Hewson, Eileen. (2008) Graveyards in Kashmir India. Wem, England: Kabristan Archives. ISBN 978-1906276072

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Srinagar. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Srinagar |

- Srinagar district administration

- Official website of Jammu and Kashmir

- Delhi to Srinagar train