Jammu and Kashmir (princely state)

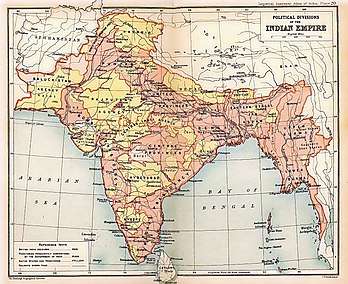

Jammu and Kashmir, also known as Kashmir and Jammu,[2] was a princely state during the British East India Company rule as well as the British Raj in India from 1846 to 1947. The princely state was created after the First Anglo-Sikh War, when the East India Company, which had annexed the Kashmir Valley,[3] Jammu, Ladakh, and Gilgit-Baltistan from the Sikhs as war indemnity, then sold the region to the Raja of Jammu, Gulab Singh, for 7,500,000 (75 lakh Nanakshahee) rupees.

Jammu and Kashmir | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1846–1952 | |||||||||||||||

Coat of Arms

| |||||||||||||||

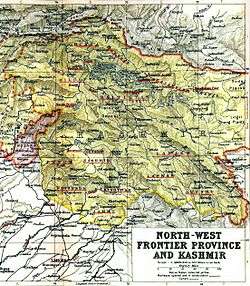

Map of Kashmir | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Princely state | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Srinagar Jammu | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Kashmiri, Dogri, Ladakhi, Balti, Shina, Pahari-Pothwari, Gujari, Kundal Shahi, Bhaderwahi, Burushaski, Brokskat, Domaaki, Khowar, Bateri, Purgi, Zangskari, Tibetan, Punjabi, Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu), Sanskrit, Sarazi | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism, Islam Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Princely state | ||||||||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||||||||

• 16 March 1846 – 30 June 1857 | Gulab Singh (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 23 September 1925 – 17 November 1952 | Hari Singh (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Dewan | |||||||||||||||

• 15 October 1947 – 5 March 1948 | Mehr Chand Mahajan (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 5 March 1948 – 17 November 1952 | Sheikh Abdullah (last) | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

| 1846 | |||||||||||||||

• Gilgit annexed by Jammu and Kashmir | 1860 | ||||||||||||||

| 1889 | |||||||||||||||

• Independence from British India | 15 August 1947 | ||||||||||||||

| 22 October 1947 | |||||||||||||||

• Accession to the Indian Union | 26–27 October 1947 | ||||||||||||||

• Constitutional state of India | 17 November 1952 | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1952 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

• Total | 85,885[1] sq mi (222,440 km2) | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Jammu and Kashmir (India) Ladakh (India) Azad Kashmir (Pakistan) Gilgit-Baltistan (Pakistan) Xinjiang (China) Tibet (China) | ||||||||||||||

At the time of the partition of India and the political integration of India, Hari Singh, the ruler of the state, delayed making a decision about the future of his state. However, an uprising in the western districts of the State followed by an attack by raiders from the neighbouring Northwest Frontier Province, supported by Pakistan, forced his hand. On 26 October 1947, Hari Singh acceded to India in return for the Indian military being airlifted to Kashmir to engage the Pakistan-supported forces, starting the Kashmir conflict[4] The western and northern districts presently known as Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan passed to the control of Pakistan, while the remaining territory remained under Indian control as the Indian-administered union territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh.[5]

Rulers

| S.no | Name | Reign | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Gulab Singh | 1846–1857 | [1] |

| 2. | Ranbir Singh | 1857–1885 | [1] |

| 3. | Pratap Singh | 1885–1925 | [1] |

| 4. | Hari Singh | 1925–1948 | [1] |

| 5. | Karan Singh (Prince Regent) | 1948–1952 |

Administration

According to the census reports of 1911, 1921 and 1931, the administration was organised as follows:[6][7]

- Jammu province: Districts of Jammu, Jasrota (Kathua), Udhampur, Reasi and Mirpur.

- Kashmir province: Districts of Kashmir South (Anantnag), Kashmir North (Baramulla) and Muzaffarabad.

- Frontier districts: Wazarats of Ladakh and Gilgit.

- Internal jagirs: Poonch, Bhaderwah and Chenani.

In the 1941 census, further details of the frontier districts were given:[6]

- Ladakh wazarat: Tehsils of Leh, Skardu and Kargil.

- Gilgit wazarat: Tehsils of Gilgit and Astore

- Frontier illaqas: Punial, Ishkoman, Yasin, Kuh-Ghizer, Hunza, Nagar, Chilas.

Prime Ministers (Jammu & Kashmir)

| # | Name | Took Office | Left Office |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Raja Sir Daljit Singh | 1917 | 1921 |

| 2 | Raja Hari Singh | 1925 | 1927 |

| 3 | Sir Albion Banerjee | January 1927 | March 1929 |

| 4 | G. E. C. Wakefield | 1929 | 1931 |

| 5 | Hari Krishan Kaul[8] | 1931 | 1932 |

| 6 | Elliot James Dowell Colvin[8] | 1932 | 1936 |

| 7 | Sir Barjor J. Dalal | 1936 | 1936 |

| 8 | Sir N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar | 1936 | July 1943 |

| 9 | Kailash Narain Haksar | July 1943 | February 1944 |

| 10 | Sir B. N. Rau | February 1944 | 28 June 1945 |

| 11 | Ram Chandra Kak | 28 June 1945 | 11 August 1947 |

| 12 | Janak Singh | 11 August 1947 | 15 October 1947 |

| 13 | Mehr Chand Mahajan | 15 October 1947 | 5 March 1948 |

| 14 | Sheikh Abdullah | 5 March 1948 | 17 November 1952 |

Geography

The area of the state extended from 32° 17' to 36° 58' N and from 73° 26' to 80° 30' E.[9] Jammu was the southernmost part of the state and was adjacent to the Punjab districts of Jhelum, Gujrat, Sialkot, and Gurdaspur. There is a fringe of level land along the Punjab frontier, bordered by a plinth of low hilly country sparsely wooded, broken, and irregular. This is known as the Kandi, the home of the Chibs and the Dogras. To travel north, a range of mountains 8,000 feet (2,400 m) high must be climbed.

This is a temperate country with forests of oak, rhododendron, chestnut, and higher up, of deodar and pine, a country of uplands, such as Bhadarwah and Kishtwar, drained by the deep gorge of the Chenab river. The steps of the Himalayan range, known as the Pir Panjal, lead to the second story, on which rests the valley of Kashmir, drained by the Jhelum river.[9]

Steeper parts of the Himalayas lead to Astore and Baltistan on the north and to Ladakh on the east, a tract drained by the river Indus. To the northwest, lies Gilgit, west and north of the Indus. The whole area is shadowed by a wall of giant mountains that run east from the Kilik or Mintaka passes of the Hindu Kush, leading to the Pamirs and the Chinese dominions past Rakaposhi (25,561 ft), along the Muztagh range past K2 (Godwin-Austen Glacier, 28,265 feet), Gasherbrum and Masherbrum (28,100 and 28,561 feet (8,705 m) respectively) to the Karakoram range which merges in the Kunlun Mountains. Westward of the northern angle above Hunza and Nagar, the maze of mountains and glaciers trends a little south of east along the Hindu Kush range bordering Chitral and so on into the limits of Kafiristan and Afghan territory.[9]

Transport

There used to be a route from Kohala to Leh; it was possible to travel from Rawalpindi via Kohala and over the Kohala Bridge into Kashmir. The route from Kohala to Srinagar was a cart-road 132 miles (212 km) in length. From Kohala to Baramulla the road was close to the River Jhelum. At Muzaffarabad the Kishenganga River joins the Jhelum and at this point the road from Abbottabad and Garhi Habibullah meet the Kashmir route. The road carried heavy traffic and required expensive maintenance by the authorities to repair.[10]

Flooding

In 1893, after 52 hours of continuous rain, very serious flooding took place in the Jhelum valley and much damage was done to Srinagar. The floods of 1903 were much more severe, a great disaster.[11]

See also

References

- David P. Henige (2004). Princely States of India: A Guide to Chronology and Rulers. Orchid Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-974-524-049-0.

- "Kashmir and Jammu", Imperial Gazetteer of India, Secretary of State for India in Council: Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 15: 71–, 1908

- Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 111–125.

- "Q&A: Kashmir dispute – BBC News".

- Bose, Sumantra (2003). Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace. Harvard University Press. pp. 32–37. ISBN 0-674-01173-2.

- Karim, Maj Gen Afsir (2013), Kashmir The Troubled Frontiers, Lancer Publishers LLC, pp. 29–32, ISBN 978-1-935501-76-3

- Behera, Demystifying Kashmir 2007, p. 15.

- Copland, Ian (1981), "Islam and Political Mobilization in Kashmir, 1931–34", Pacific Affairs, 54 (2): 228–259, JSTOR 2757363

- "Kashmir and Jammu" Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 15, p. 72.

- "Kashmir and Jammu" Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 15, p. 79.

- "Kashmir and Jammu" Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 15, p. 89

Bibliography

- Behera, Navnita Chadha (2007), Demystifying Kashmir, Pearson Education India, ISBN 8131708462

- Das Gupta, Jyoti Bhusan (2012), Jammu and Kashmir, Springer, ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6

- Birdwood, Lord (1956), Two Nations and Kashmir, R. Hale

- Huttenback, Robert A. (1961), "Gulab Singh and the Creation of the Dogra State of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh" (PDF), The Journal of Asian Studies, 20 (4): 477–488, doi:10.2307/2049956, archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2016

- Mahajan, Mehr Chand (1963), Looking Back: The Autobiography of Mehr Chand Mahajan, Former Chief Justice of India, Asia Publishing House

- Major, Andrew J. (1996), Return to Empire: Punjab under the Sikhs and British in the Mid-nineteenth Century Limited, New Delhi: Sterling Publishers, ISBN 81-207-1806-2

- Major, Andrew J. (1981), Return to Empire: Punjab under the Sikhs and British in the Mid-nineteenth Century, Australian National University

- Noorani, A. G. (2011), Article 370: A Constitutional History of Jammu and Kashmir, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-807408-3

- Panikkar, K. M. (1930). Gulab Singh. London: Martin Hopkinson Ltd.

- Raghavan, Srinath (2010), War and Peace in Modern India, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 101–, ISBN 978-1-137-00737-7

- Rai, Mridu (2004), Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir, C. Hurst & Co, ISBN 1850656614

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, ISBN 1860648983

- Singh, Bawa Satinder (1971), "Raja Gulab Singh's Role in the First Anglo-Sikh War", Modern Asian Studies, 5 (1): 35–59, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00002845, JSTOR 311654

This article incorporates text from the Imperial Gazetteer of India, a publication now in the public domain.