Sagunto

Sagunto ([saˈɣunto]; Valencian: Sagunt [saˈɣunt]) is a city in Eastern Spain, in the modern fertile comarca of Camp de Morvedre in the province of Valencia. It is located c. 30 km north of Valencia, close to the Costa del Azahar on the Mediterranean Sea.

Sagunto Sagunt | |

|---|---|

| Sagunt / Sagunto | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

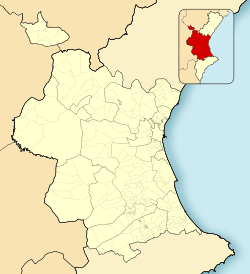

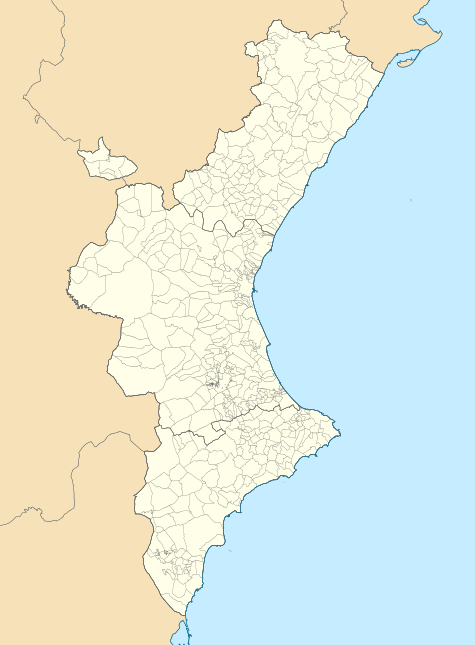

Sagunto Location in Spain  Sagunto Sagunto (Valencian Community)  Sagunto Sagunto (Spain) | |

| Coordinates: 39°40′35″N 0°16′24″W | |

| Country | |

| Autonomous community | |

| Province | Valencia |

| Comarca | Camp de Morvedre |

| Founded | Before 219 BC |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council government |

| • Body | Ajuntament de Sagunt |

| • Mayor | Darío Moreno Lerga (2019-) (PSPV PSOE) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 132 km2 (51 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 49 m (161 ft) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 65,669 |

| Demonym(s) | Saguntí, saguntina Morvedrí, morvendrina |

| Native Language | Valencian (Catalan) |

| Official languages | Valencian (Catalan) Spanish |

| Website | Official website |

It is best known for the remains of the ancient Iberian and Roman city of Saguntum, which played a significant part in the Second Punic War between the Carthaginians and the Romans.

History

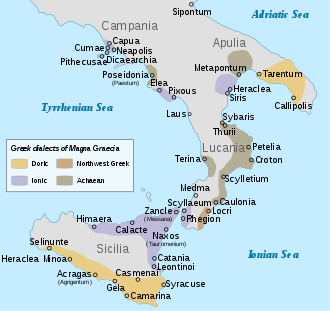

Achaeans, probably from the Greek island of Zakynthos, founded in the 5th c. BCE the town Zacynthos (now Zakantha or Sagundo), at the foot of the Peñas de Pajarito and on the west bank of river Palancia of the main river Ebro, in Iberia, in the Valencia province [Appian, Wars in Spain, 2], where the vestiges of an Acropolis, Temples of Artemis and Aphrodite, and a small Theater still survive. During the 5th century BC, the Iberians built a walled settlement on the hill overseeing the plain; a stretch of cyclopean limestone slabs from the former temple of Diana survives, close to the modern church of Santa Maria, but the settlement site is still older. The city traded with coastal colonies in the western Mediterranean such as Carthage and, under their influence, minted its own coins. During this period, the city was known as Arse (Ripollès i Alegre 2002). By 219 BC, Saguntum was a large and commercially prosperous town, which sided with the local colonists and Rome against Carthage, and drew Hannibal's first assault, his siege of Saguntum, which triggered the Second Punic War, one of the most important wars of antiquity.

After stiff resistance over the course of eight months, related by the Roman historian Livy[2] and in more detail by Silius Italicus,[3] Saguntum was captured in 219 BC by the armies of Hannibal.

Seven years later, the town was retaken by the Romans. In 214 BC, it became a municipium, was rebuilt and flourished. Hispania was not easily pacified and Romanised, as the Iberian career of Quintus Sertorius makes clear. Saguntum minted coins under his protection, but continued to house a mint in later Roman times. The Romans built a great circus in the lower part of the city and a theatre seating 8,000 spectators. Texts found indicate that the city had an amphitheatre and had about 50,000 inhabitants. This prosperity lasted for most of the empire, and is attested by inscriptions and ruins (notably a theatre, demolished by Napoleon's marshal Louis Gabriel Suchet, who also destroyed the Roman tower of Hercules).

Under the Arian Visigothic kings, Saguntum received its Catholic patron saint, a bishop named Sacerdos, "the priest", who died peacefully of natural causes about AD 560.

In the early 8th century, the Muslim Arabs conquered Hispania and the city became part of the Caliphate of Cordoba and at that time the city reached an era of splendor, with baths, palaces, mosques and schools open for its cosmopolitan population. Then, the town was known as Morvedre (Morviedro in Spanish), a name derived from Latin muri veteres "ancient walls." However, as Valencia grew, Saguntum declined.

In 1098, the city was conquered by El Cid but the Muslims recovered it shortly thereafter. The city had been under the Muslim Arab rule for over 500 years when James I of Aragon conquered it in 1238.

During the Peninsular War, a Spanish attempt to raise the French siege of the castle failed in the Battle of Saguntum on 25 October 1811. In the weeks before the battle, the Spanish garrison made a valiant and successful defense; but it surrendered the day after the battle.[4] Historian Charles Oman stated that the site was converted into a fortress in 1810–1811 by General Joaquín Blake at the suggestion of British officer Charles William Doyle. At that time, much of the largely intact Roman theater was dismantled to provide stone for restoring the old walls.[5]

Saguntum was badly damaged in warfare, but has retained many Valencian Gothic structures. In the late 19th century, a steel-making industry grew up that supported the modern city, which extends in the coastal plain below the citadel hill. The last steel oven closed in April 1984. It has been restored and is now a tourist attraction.

Main sights

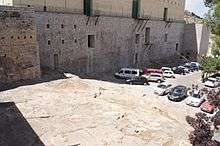

- The remains of Sagunto Castle may be seen on top of the hill. It preserves much of its walled ramparts, of Roman and Moorish origin.

- A Roman theater, partly restored in late 20th century. It is found on the northern slope of the citadel hill. It was the first official National Monument declared in Spain (1896).

- The Gothic Esglèsia de Santa Maria (St Mary's Church), in the Plaça Major (Main Square).

- The Palau Municipal (City Palace), or town hall; a beautiful 18th century building with a neoclassical façade.

- The early Gothic Esglèsia del Salvador (Church of Our Savior).

- The narrow streets of the Juderia (Old Jewish Quarter), on the hillside on the way up to the citadel.

- The 13th century Santa Ana convent adjacent to the Plaça de Pi.

- The Sagunto History Museum, located in the house of Mestre Peña, a building in the Jewish quarter dating from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The largest collection is from the Ibero-Roman Period.

The famed composer Don Joaquín Rodrigo, who composed Concierto de Aranjuez, among others, was born in Sagunt.

Notes

- Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- Livy: History of Rome

- Silius Italicus: Punica

- Oman 1996, pp. 31–46.

- Oman 1996, pp. 11–12.

References

- Ripollès i Alegre, P.P. (2002). Arse-Saguntum: historia monetaria de la ciudad y su territorio. Fundación Bancaja. ISBN 8484710270.

- Oman, Charles (1996) [1914]. A History of the Peninsular War Volume V. 5. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole. ISBN 1-85367-225-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sagunt - Sagunto. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Sagunto. |