Proto-Min

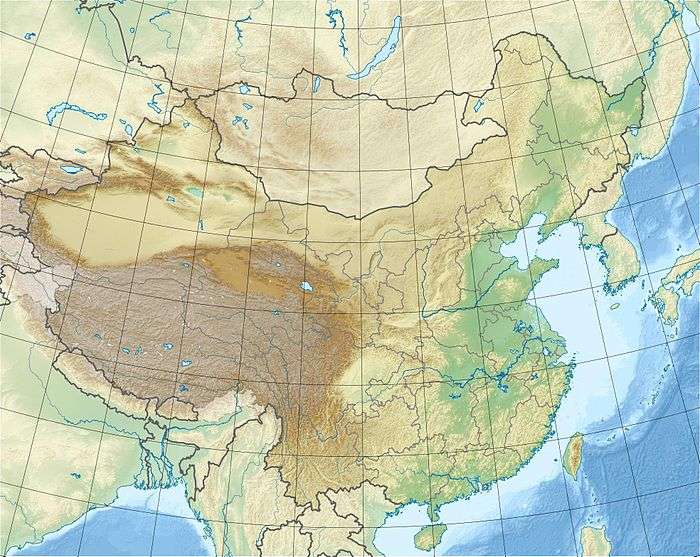

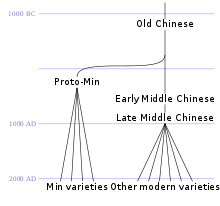

Proto-Min is a comparative reconstruction of the common ancestor of the Min group of varieties of Chinese. Min varieties developed in the relative isolation of the Chinese province of Fujian and eastern Guangdong, and have since spread to Taiwan, southeast Asia and other parts of the world. They contain reflexes of distinctions not found in Middle Chinese or most other modern varieties, and thus provide additional data for the reconstruction of Old Chinese.

| Proto-Min | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reconstruction of | Min Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Region | Fujian | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Era | c. 100 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 原始閩語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 原始闽语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Jerry Norman reconstructed the sound system of proto-Min from popular vocabulary in a range of Min varieties, including new data on varieties from inland Fujian. The system has a six-way manner contrast in stops and affricates, compared with the three-way contrast in Middle Chinese and modern Wu varieties and the two-way contrast in most modern Chinese varieties. A two-way contrast in sonorants is also reconstructed, compared with the single series of Middle Chinese and all modern varieties. Evidence from early loans into other languages suggests that the additional contrasts may reflect consonant clusters or minor syllables.

Min dialects

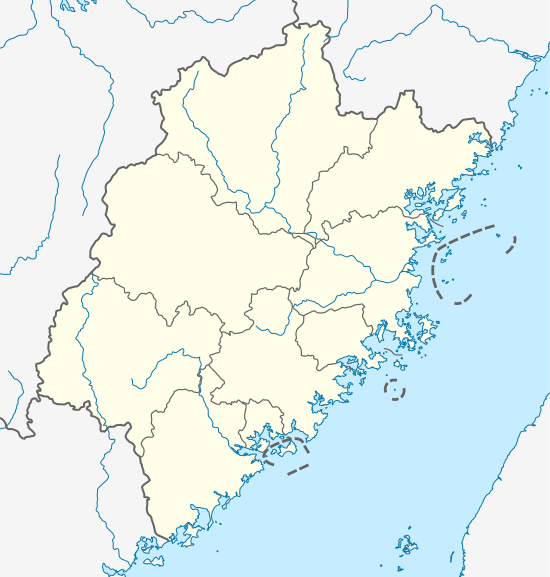

The Min homeland consists of most of the province of Fujian, and the adjacent eastern part of Guangdong. The area features rugged mountainous terrain, with short rivers that flow into the South China Sea. After the area was first settled by Chinese during the Han dynasty, most subsequent migration from north to south China passed through the valleys of the Xiang and Gan rivers to the west. Min varieties have thus developed in relative isolation.[1]

Separation from common Chinese

As described in rhyme dictionaries such as the Qieyun (601 AD), Middle Chinese initial stops and affricate consonants showed a three-way contrast between voiceless unaspirated, voiceless aspirated and voiced consonants. There were four tones, with the fourth, the "entering tone", a checked tone comprising syllables ending in stops (-p, -t or -k).

This syllable structure was also found in neighbouring languages of the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area – Proto-Hmong–Mien, Proto-Tai and early Vietnamese – and is largely preserved by early loans between the languages.[2] Towards the end of the first millennium AD, all of these languages experienced a tone split conditioned by initial consonants. Each tone split into an upper (yīn 阴/陰) register consisting of words with voiceless initials and a lower (yáng 阳/陽) register of words with voiced initials. When voicing was lost in most varieties, the register distinction became phonemic, yielding up to eight tonal categories, with a six-way contrast in unchecked syllables and a two-way contrast in checked syllables.[3]

The traditional classification of varieties of Chinese distinguished seven groups according to the reflexes of Middle Chinese voiced initials in various tonal categories.[4] For example, voiced stops are preserved in the Wu and Old Xiang groups, have merged with aspirated or unaspirated stops depending on the tone in Mandarin, and have uniformly become aspirated stops in Gan and Hakka.[5] The distinguishing characteristic of Min varieties is that voiced stops yield both aspirated and unaspirated stops in all tonal categories. Further, the distribution is consistent across Min varieties, suggesting a common ancestor in which two types of voiced stop were distinguished.[6]

Min must have diverged before two changes in other Chinese varieties (including Middle Chinese) that are not reflected in Min:

- The Old Chinese finals *-jaj and *-je merged after velar initials. This merger is reflected in a change in poetic rhyme between the Western Han (206 BC to 9 AD) and Eastern Han (25–220 AD) periods.[7]

- Old Chinese velar initials palatalized in certain environments during the Western Han period.[8] For example, Middle Chinese tsye 'branch' 支/枝 is believed to reflect palatalization of an Old Chinese initial *k- because other words written with the same phonetic component, such as gjeX 'skill' 伎/技, have velar initials. The proto-Min form *kiA 'branch' retains the original initial.[9]

However, the palatalization of dental stop initials, which had occurred in some dialects by the Eastern Han period, is common to Middle Chinese and Min.[10] Baxter and Sagart suggest that the later part of the Proto-Min period may have overlapped with Early Middle Chinese.[11]

Pointing to features of Min varieties that are also found in Hakka and Yue varieties, Jerry Norman suggests that the three groups are descended from a variety spoken in the lower Yangtze region during the Han period, which he calls Old Southern Chinese.[12] He argues that this dialect belonged to the group of dialects known as Wu (吳) or Jiangdong (江東) in the Western Jin period, when the writer Guo Pu (early 4th century AD) described them as quite distinct from other Chinese varieties.[13] Some of the distinctive Jiangdong words mentioned by Guo Pu appear to be preserved in modern Min varieties, including Proto-Min *giA 'leech' and *lhɑnC 'young fowl'.[14] This language entered Fujian after the area was opened to Chinese settlement by the defeat of the Minyue state by the armies of Emperor Wu of Han in 110 BC.[15] Norman argues that Hakka and Yue have resulted from overlays of this language by successive waves of influence from northern China.[16]

When Chinese soldiers and settlers moved south from their homeland in the North China Plain, they came into contact with speakers of Tai–Kadai, Hmong–Mien and Austroasiatic languages. Early loans from Chinese into these languages date from around Han times and thus contain evidence of the sounds of Chinese as spoken in the south at that time.[17]

Strata

Norman identifies four main layers in the vocabulary of modern Min varieties:

- A non-Chinese substratum from the original languages of Minyue, which Norman believes were Austroasiatic.[18] These etymologies have been disputed by Laurent Sagart, and there is no other evidence for an early Austroasiatic presence in southeast China.[19]

- The earliest Chinese layer, brought to Fujian by settlers from Zhejiang to the north during the Han dynasty.[13]

- A layer from the Northern and Southern dynasties period, largely consistent with the phonology of the Qieyun dictionary, which was published in 601 AD but based on earlier dictionaries that are now lost.[20]

- A literary layer based on the koiné of Chang'an, the capital of the Tang dynasty.[21]

Since the two later layers can largely be derived from the Qieyun, Norman sought to focus on the earlier layers.[20]

Subgroups

Early classifications, such as those of Li Fang-Kuei in 1937 and Yuan Jiahua in 1960, divided Min into Northern and Southern subgroups.[22][23] However, in a 1963 report on a survey of Fujian, Pan Maoding and colleagues argued that the primary split was between inland and coastal groups.[24] The inland varieties are distinguished by consistently having two distinct reflexes of Middle Chinese /l/.[23] The two groups also have differences in their vocabulary, including their pronoun systems.[25]

The coastal dialects are divided into three subgroups:[26]

- Eastern Min

- including Fuzhou, Ningde and Fu'an in northeast Fujian

- Pu-Xian Min

- including Putian and Xianyou on the central Fujian coast

- Southern Min

- including Xiamen, Zhangzhou and Quanzhou in southern Fujian, and Chaozhou, Jieyang and Shantou in eastern Guangdong

They divided the inland dialects into two subgroups:

- Northern Min

- including Jianyang, Jian'ou, Chong'an, Zhenghe and Shibei

- Central Min

- including Sanming and Yong'an in western Fujian

Several varieties in the far west of Fujian include features of Min and the neighbouring Gan and Hakka groups, making them difficult to classify. In the Shaojiang dialects, spoken in the northwestern Fujian counties of Shaowu and Jiangle, the reflexes of Middle Chinese voiced stops are uniformly aspirated, as in Gan and Hakka, leading some workers to assign them to one of these groups. Pan et al. described them as intermediate between Min and Hakka.[27] However, Norman showed that their tonal development could only be explained in terms of the same two classes of voiced initial assumed for Min dialects. He suggested that they were inland Min dialects that had been subject to heavy Gan or Hakka influence.[28] Norman's student David Prager Branner argued that the varieties of Longyan and the township of Wan'an, in the southwestern part of the province, were coastal Min varieties, but outside of the three subgroups identified by Pan.[29][30]

Initials

In a series of papers from 1973, Jerry Norman sought to reconstruct the initial consonants of proto-Min by applying the comparative method to pronunciations in modern Min varieties. For this purpose, rather that the traditional approach of soliciting readings of character lists, he focussed on everyday vocabulary and excluded words of literary origin.[31]

| Labial | Dental | Lateral | Sibilant | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voiceless stops and affricates |

aspirated | ph | th | tsh | tšh | kh | ||

| unaspirated | p | t | ts | tš | k | ʔ | ||

| "softened" | -p | -t | -ts | -tš | -k | |||

| Voiced stops and affricates |

aspirated | bh | dh | dzh | džh | gh | ||

| unaspirated | b | d | dz | dž | g | |||

| "softened" | -b | -d | -dz | -dž | -g | |||

| Sonorants | plain | m | n | l | ń | ŋ | ∅ | |

| aspirated | mh | nh | lh | (ńh) | ŋh | |||

| Fricatives | voiceless | s | š | x | ||||

| voiced | z | ž | ɣ | ɦ | ||||

The inventory of proto-Min initials differs from that of Middle Chinese (as deduced from the Qieyun rhyme book and its successors) in several ways:

- Middle Chinese has two series of retroflex initials that are not found in proto-Min.[34][35]

- Whereas Middle Chinese obstruents have a three-way manner distinction, proto-Min has a six-way distinction: both voiced and voiceless stops may be aspirated or unaspirated, and also have an additional series that Norman called "softened".[36]

- Proto-Min has two series of sonorants.[37]

- Proto-Min distinguishes voiced fricatives *ɣ and *ɦ.[36]

The most controversial have been the "softened" stops and affricates, so named because they have lateral or fricative reflexes in some Northern Min varieties centred on Jianyang. These initials also have distinct tonal reflexes in the Northern Min and Shaojiang groups, but have merged with unaspirated stops and affricates in coastal varieties. Other scholars have suggested that the patterns observed in northwest Fujian can be explained as a mixture of forms from neighbouring Wu, Gan and Hakka varieties, though this does not explain the regularity of the correspondences.[38] In addition, the forms of many of the words in the proposed donor varieties do not match the Min reflexes, and some of the words occur only in Min.[39]

Since the pioneering reconstruction of Bernhard Karlgren, Old Chinese has been reconstructed by projecting the categories of Middle Chinese back onto the rhyming patterns of the Classic of Poetry and the shared phonetic components of Chinese characters. Thus Old Chinese is usually reconstructed with the same three-way manner distinction in obstruent initials found in Middle Chinese. However this does not preclude additional manner distinctions that merged in Middle Chinese, because rhyme gives no information about initials and sharing of phonetic components indicates initials with the same place of articulation but not necessarily the same manner.[40] Several scholars have attempted to incorporate proto-Min data into their reconstructions of Old Chinese. The most systematic attempt to date is the reconstruction of Baxter and Sagart, who derive the additional initials from a number of initial consonant clusters and minor syllables.[41]

Voiceless stops and affricates

All modern Min varieties have a two-way contrast between unaspirated and aspirated voiceless stops and affricates.[lower-alpha 1] Where these initials occur with upper register tones, they are projected back into proto-Min, and correspond to unaspirated and aspirated voiceless initials in Middle Chinese. However, some Middle Chinese voiceless unaspirated initials correspond to fricatives or laterals in Northern Min, and also have a special tonal development in Northern Min and Shao–Jiang. Norman called these initials voiceless "softened" stops and affricates.[43]

| pMin | Xiamen | Fuzhou | Jian'ou | Jianyang | Shaowu | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *ph | pʰ | pʰ | pʰ | pʰ | pʰ | 拍 hit, 破 break, broken, 簿 register (n.), 蜂 bee |

| *p | p | p | p | p | p | 八 eight, 分 share, 半 half, 板 board |

| *-p | p | p | p/∅ | v/∅ | pʰ | 反 reverse (v.), 崩 collapse, fall over, 楓 maple, 沸 boil (v.), 發 emit, 補 repair, 飛 fly (v.) |

| *th | tʰ | tʰ | tʰ | h | tʰ | 天 sky, 炭 charcoal, 腿 leg, 鐵 iron |

| *t | t | t | t | t | t | 單 list, 帶 belt, 桌 table, 短 short |

| *-t | t | t | t | l | tʰ | 擔 carry on the shoulder, 賭 wager, 轉 turn |

| *tsh | tsʰ | tsʰ | tsʰ | tsʰ/tʰ | tsʰ | 秋 autumn, 草 grass, 菜 vegetable, 青 green |

| *ts | ts | ts | ts | ts | ts | 做 make, 姊 elder sister, 竈 stove, 節 holiday, 酒 liquor |

| *-ts | ts | ts | ts | l | tsʰ | 䭕 insipid, 早 early, 淡 unsalty, 簪 hairpin, 醉 drunk |

| *tšh | tsʰ | tsʰ | tsʰ | tsʰ/tʰ | tʃʰ | 唱 to lead (in singing), 戍 house, 深 deep, 臭 smelly, 醒 awake |

| *tš | ts | ts | ts | ts | tʃ | 正 correct, 汁 juice, 紙 paper, 針 needle |

| *-tš | ts | ts | ts | ∅ | tʃ | 指 finger |

| *kh | kʰ | kʰ | kʰ | kʰ | kʰ | 勸 advise, 客 guest, 苦 bitter, 開 open, 骹 foot |

| *k | k | k | k | k | k | 嫁 marry, 救 save, 教 teach, 枝 branch, 桔 tangerine, 瓜 melon, 繭 cocoon, 肝 liver, 角 horn, 記 remember, 雞 chicken, 韮 type of leek |

| *-k | k | k | ∅ | ∅/h | k | 割 cut (v.), 狗 dog, 缸 jar, 膏 lard, 飢 hungry |

In loans from southern Chinese into proto-Hmong–Mien, softened obstruents are often represented by prenasalized consonants.[47] Norman suggests the proto-Min initials were also prenasalized,[48] whereas Baxter and Sagart derive them from stops preceded by minor syllables, arguing that the intervocalic environment caused the stops to weaken to fricatives in some dialects.[49]

Voiced stops and affricates

In most varieties of Chinese that have lost the voicing of Middle Chinese initials, the aspiration of the resulting initials is conditioned by tone, though the relationship varies between dialect groups. In Min varieties however, both aspirated and unaspirated voiceless initials are found in lower register tones. These initials must therefore be distinguished in proto-Min as aspirated and unaspirated voiced consonants. In Shao–Jiang these initials are uniformly aspirated, but the same distinction is reflected in the tonal development. As with the voiceless initials, there is a third group of formerly voiced initials with fricative or lateral reflexes in some Northern Min varieties, which Norman called "softened" voiced initials.[50] In Eastern Min varieties, voiced unaspirated affricates typically yielded plain /s/.[51]

| pMin | Xiamen | Fuzhou | Jian'ou | Jianyang | Shaowu | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *bh | pʰ | pʰ | pʰ | pʰ | pʰ | 伴 escort, 曝 shine, 皮 skin, 稗 tare, 薸 duckweed, 被 cover, 雹 hail, 鼻 nose |

| *b | p | p | p | p | pʰ | 平 level, 爬 climb, 病 ill, 白 white, 盤 dish, 耙 harrow, 肥 fat (adj.), 飯 rice |

| *-b | p | p | p | v | pʰ | 吠 bark (v.), 婦 daughter-in-law, 拔 pull, 步 stride, 浮 float (v.), 瓶 vase, 盆 bowl, 簰 raft, 薄 thin |

| *dh | tʰ | tʰ | tʰ | h | tʰ | 啼 weep, 杖 staff, 柱 pillar, 桃 peach, 椎 hammer, 疊 stack up, 蟲 bug, 頭 head, 餳 sugar |

| *d | t | t | t | t | tʰ | 住 reside, 弟 younger brother, 斷 break off, 直 straight, 筒 tube, 茶 tea, 豆 bean, 踏 step on, 蹄 hoof, 重 heavy |

| *-d | t | t | t | l | tʰ | 値 worth, 動 move, 毒 poison, 脰 neck, 舵 rudder, 袋 bag, 銅 copper, 長 long |

| *dzh | tsʰ | tsʰ | tsʰ | tsʰ/tʰ | tsʰ | 柴 wood, 牀 bed, 田 field, 賊 thief |

| *dz | ts | s/ts | ts | ts | tsʰ | 坐 sit, 截 to cut off, 晴 clear (weather), 槽 trough, 自 self (adv.), 錢 money |

| *-dz | ts | s/ts | ts | l | tsʰ | 字 character, 罪 crime, 謝 decline, 齊 together |

| *džh | tsʰ | tsʰ | s | s/tsʰ | ʃ | 席 mat, 樹 tree, 象 resemble, 鱔 eel |

| *dž | ts | s | ts | ts | ʃ | 上 top, 石 stone, 薯 yam, 裳 clothing |

| *-dž | ts | s | ∅ | ∅ | ʃ | 上 ascend, 嘗 taste (v.), 舌 tongue, 船 boat, 蛇 snake |

| *gh | kʰ | kʰ | kʰ | kʰ | kʰ | 柿 persimmon, 臼 mortar, 踦 stand, 騎 ride |

| *g | k | k | k | k | kʰ | 妗 aunt, 橋 bridge, 汗 sweat (n.), 舊 old, 茄 eggplant, 跪 kneel |

| *-g | k | k | k | k/∅ | kʰ/h | 厚 thick, 含 hold in the mouth, 咬 bite, 滑 slippery, 猴 monkey, 球 ball, 縣 district |

There are several cases where an adjective or intransitive verb beginning with an unaspirated voiced stop is paired with a transitive verb differing only in aspiration of the voiced stop, suggesting that the contrast reflects an early morphological process.[56]

Early loans from southern Chinese into proto-Hmong–Mien have prenasalized stops corresponding to both aspirated and softened voiced stops in proto-Min.[57] Baxter and Sagart derive aspirated voiced stops from tightly bound nasal preinitials in Old Chinese, and softened voiced stops from voiced stops preceded by minor syllables.[57]

Sonorants

Inland Min varieties are characterized by having two distinct reflexes of Middle Chinese /n/, which Norman labels as proto-Min *l and *lh. The two have merged in coastal varieties. In modern Southern Min varieties such as Hokkien, /l/ and /n/ comprise a single phoneme, realized as /n/ before nasalized vowels and as /l/ in other syllables.[37] Two series of nasals can also be distinguished based on their tonal reflexes in Eastern Min and Shao-Jiang. They generally produce a single series of nasal initials in modern varieties except in Southern Min. In those varieties, the proto-Min initials *nh and *ŋh have become /h/ before high front vowels, *m, *n and *ŋ denasalized to *b, *l and *g respectively before oral vowels, but *mh and other occurrences of *nh and *ŋh often yield nasals in that context.[58][42]

| pMin | Xiamen | Fuzhou | Jian'ou | Jianyang | Shaowu | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *l | l/n | l | l | l | l | 來 come, 流 flow (v.), 犁 plow, 籠 cage, 綠 green, 落 fall (v.), 蠟 wax, 辣 pungent |

| *lh | l/n | l | s | s | s | 兩 two, 六 six, 利 sharp, 劉 a surname, 卵 egg, 李 plum, 留 remain, 笠 rain-hat, 籃 basket, 籮 hamper, 老 old, 聾 deaf, 蘆 reed, 螺 snail, 貍 wildcat, 郎 young man, 雷 thunder, 露 dew, 鱗 scale (or fish or reptile) |

| *m | m | m | m | m | m | 命 life, 慢 slow, 梅 plum, 煤 coal, 盲 blind, 磨 grind, whet, 蜜 honey, 賣 sell, 門 gate, door, 麥 wheat |

| *mh | m/b | m | m | m | m | 名 name, 問 ask, 夢 dream, 妹 sister, 目 eye, 罵 scold, 蚊 mosquito, 貓 cat, 面 face, 麻 hemp |

| *n | n/l | n | n | n | n | 南 south, 念 read |

| *nh | n/h | n | n | n | n | 年 year, 肉 meat, 膿 pus, 讓 allow (want) |

| *ń | dz | n | n | n | n | 二 two, 日 day, 認 recognize, 閏 intercalary |

| *ŋ | ŋ/g/h | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ/n | 五 five, 外 outside, 月 moon, 玉 jade, 銀 silver, 魚 fish, 鵝 goose |

| *ŋh | h | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ/n | 硯 ink-stone, 艾 moxa, 額 forehead |

As the initials *lh, *nh, etc. follow the same tonal development as voiced aspirated initials throughout Min, Norman suggests that they were characterized by breathy voice.[61] In Hakka dialects, nasals appear in both lower and upper register tones, suggesting a protolanguage with both voiced and voiceless nasals. Moreover, the occurrence of these initials corresponds to the plain and aspirated nasals of proto-Min.[62] Norman suggests that they derive from voiced and voiceless nasals in Old Southern Chinese. Further evidence for a voicing distinction comes from early loans into Vietnamese and the Mienic and Tai languages.[63] Norman later abandoned the *ń initial, treating the dz-/z- initials in some Southern Min varieties as arising from *n followed by a high front vowel *i or *y.[64][65]

A different set of voiceless resonant initials is proposed in most recent reconstructions of Old Chinese, with fricative reflexes in Middle Chinese.[66] Norman suggests that Old Southern Chinese voiceless sonorants derive from sonorants preceded by voiceless consonants.[67] William Baxter and Laurent Sagart have incorporated this proposal into their reconstruction of Old Chinese.[68]

Fricatives and others

Fricatives in upper and lower registers are assumed to derive from voiceless and voiced fricatives respectively, broadly corresponding to the voiceless and voiced fricatives of Middle Chinese.[36] Zero initials show three distinct patterns of tonal development, reconstructed as initials *ɦ, *ʔ and a proto-Min zero initial. The latter occurs only before the high front vowels *i and *y.[69]

| pMin | Xiamen | Fuzhou | Jianyang | Yongan | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *s | s | s | s | s | 三 three, 四 four, 山 mountain, 想 think |

| *z | s | s | s | ʃ | 翼 wing, 蠅 fly, 鹽 salt (n.), 鹽 to salt |

| *š | s | s | s | ʃ/s | 使 use, 聲 voice, 蝨 louse, 詩 poetry, 身 body |

| *ž | s | s | s | s/ʃ | 成 become, 是 is, are, 時 time, 熟 mature |

| *x | h | h | x | h/ʃ | 好 good, 海 sea, 火 fire, 花 flower (n.), 虎 tiger, 許 Xu (surname) |

| *ɣ | h | h | x | h/ʃ | 園 garden, 巷 lane, 橫 horizontal, 雨 rain |

| *ʔ | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ | 啞 mute, 応 answer, 椅 chair, 飲 rice-water |

| *ɦ | ∅ | ∅ | ∅/h | ∅ | 下 down, 學 learn, 會 able, 鞋 shoe |

| *∅ | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ | 圓 round, 後 after, 有 have, exist, 羊 goat, 葯 medicine, 閑 idle, 黃 yellow |

In Central Min, *s and *x merged as /ʃ/ before high front vowels.[72]

Tones

Proto-Min had four tone classes, corresponding to the four tones of Middle Chinese: syllables with vocalic or nasal endings belonged to class *A, *B or *C, whereas class *D consisted of the syllables ending in a stop (/p/, /t/ or /k/).[73] As with Middle Chinese and other languages of the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, each of these classes split into upper and lower registers, depending on whether the original initial was voiceless or voiced.[74] When voicing was lost,[lower-alpha 2] the register distinction became phonemic, yielding tone classes conventionally numbered 1 to 8, with tones 1 and 2 naming the upper and lower registers of proto-Min class A*, and so on.[73] All 8 classes are retained by the Chaozhou dialect, but some have merged in other varieties. Some northern varieties, including the Jianyang dialect, have an additional tone class (tone 9), reflecting a partial merger of tone classes that cannot be predicted from Middle Chinese forms.[76]

| Tone class *A | Tone class *B | Tone class *C | Tone class *D | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *th | *t | *-t | *n | *nh | *dh | *d | *-d | *th | *t | *-t | *n | *nh | *dh | *d | *-d | *th | *t | *-t | *n | *nh | *dh | *d | *-d | *th | *t | *-t | *n | *nh | *dh | *d | *-d | ||

| Chaozhou | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xiamen | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fuzhou | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yong'an | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ?[lower-alpha 3] | 5 | 7 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jianyang | 1 | 9 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Jian'ou | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Shaowu | 1 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 5 | ? | 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||

Stop and affricate initials at other points of articulation produce the same tonal reflexes as the dental examples in the above table. Voiceless fricatives have the same tonal reflexes as voiceless aspirated and unaspirated stops. Voiced fricatives are more varied:[81]

- The initials *z and *ɣ have the same tonal reflexes as aspirated nasals and voiced aspirated stops.

- The initial *ž follows voiced unaspirated stops.

- The initial *ɦ follows softened voiced stops.

The zero initial has the same tonal development as plain sonorants.[82]

Finals

Norman reconstructs proto-Min finals as consisting of:

- an optional medial *i, *u or *y,

- a nuclear vowel *i, *u, *y, *e, *ə, *o, *a or *ɑ, and

- an optional coda *i, *u, *m, *n, *ŋ, *p, *t or *k.[83]

The possible combinations were:

| *e | *o | *a | ||||

| *i | *ie | *io | *ia | (*iɑ)[lower-alpha 4] | ||

| (*uə)[lower-alpha 5] | *ua | |||||

| *y | *ye | |||||

| *əi | *oi | *ɑi | ||||

| *iɑi | ||||||

| (*ui)[lower-alpha 6] | (*uəi)[lower-alpha 7] | (*uai)[lower-alpha 8] | *uɑi | |||

| *yi | (*yəi)[lower-alpha 9] | |||||

| *eu | *əu | *au | *ɑu | |||

| *iu | *iau | |||||

| *em/p | (*əm/p)[lower-alpha 10] | *am/p | *ɑm/p | |||

| *im/p | *iam/p | *iɑm/p | ||||

| *ən/t | *on/t[lower-alpha 11] | *an/t | *ɑn/t | |||

| *in/t | *iun/t | *ion/t | *ian/t | *iɑn/t[lower-alpha 12] | ||

| *un/t | (*uon/t)[lower-alpha 13] | (*uan/t)[lower-alpha 14] | *uɑn/t | |||

| (*yn/t)[lower-alpha 15] | (*yan)[lower-alpha 16] | |||||

| *eŋ/k | *əŋ/k | *oŋ/k | *aŋ/k | |||

| *ioŋ/k | *iaŋ/k | |||||

| *uoŋ/k | (*uaŋ/k)[lower-alpha 17] | |||||

| *yŋ/k | *yok |

The close vowels *i, *u, *y, *e and *ə were short, with stronger following consonants, whereas the open vowels *o, *a and *ɑ were longer, with weaker following consonants.[96][97]

Proto-Min also had a single word with a syllabic nasal, the usual negator *mC (cognate with Middle Chinese mjɨjH 未 'not have').[98][99]

Sound changes leading to modern varieties

Most inland varieties have reduced the nasal codas to a single category.[42] Coastal varieties went through a series of changes that each affected part of the area, and interacted with nasal initials:

- In Southern Min, Pu-Xian and Hainan varieties, nasal codas disappeared after open vowels, leaving nasalized vowels.[96][97]

- In Southern Min, Pu–Xian and Hainanese, nasal initials became voiced stops or flaps except before nasalized vowels or nasal codas. In Hokkien, denasalization also occurred before nasal codas, but not before nasalized vowels.[100][75] In Pu-Xian, these initials later devoiced, merging with the voiceless unaspirated stops.[101]

- Vowels subsequently lost their nasalization in Putian and Hainan.[97][102]

- A later merger of nasal codas as /ŋ/ occurred in Pu–Xian and some Eastern Min dialects, including Fuzhou, Fuding and Gutian, but not Fu'an and Ningde.[97][103] A partial merger occurred in Chaozhou, Jieyang and Shantou, where -n merged with -ŋ.[101][42]

| Southern | Eastern | Northern | Central | Shao–Jiang | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| word | Proto-Min | Jieyang | Xiamen | Fuzhou | Fu'an | Jian'ou | Jianyang | Yong'an | Jiangle |

| 南 south | *nəmA | nam2 | lam2 | naŋ2 | nam2 | naŋ5 | naŋ2 | nɔ̃2 | naŋ9 |

| 慢 slow | *mənC | maŋ6 | man6 | maiŋ6 | mɛn2 | maiŋ6 | maiŋ6 | mĩ5 | maĩ6 |

| 崩 collapse | *-peŋA | paŋ1 | paŋ1 | puŋ1 | poŋ1 | paiŋ3 | vaiŋ9 | pĩ1 | pʰãi3 |

| 三 three | *sɑmA | sã1 | sã1 | saŋ1 | sam1 | saŋ1 | saŋ1 | sɔ̃1 | saŋ1 |

| 山 mountain | *sɑnA | suã1 | suã1 | saŋ1 | san1 | sueŋ1 | sueŋ1 | sũm1 | ʃuãi1 |

| 生 give birth | *šaŋA | sẽ1 | sĩ1 | saŋ1 | saŋ1 | saŋ1 | saŋ1 | sɔ̃1 | ʃaŋ1 |

In most inland varieties stop codas have disappeared, but are marked with separate tonal categories.[42] In coastal varieties, stop codas underwent changes corresponding to those affecting nasal codas:

- Final stops following open vowels merged as a glottal stop in Southern Min, Pu–Xian and Hainanese.[96][97] In Eastern Min, only final *k changed to a glottal stop in this environment.

- This glottal stop then disappeared in Pu–Xian.[97]

- Stop codas merged as /k/ in Pu–Xian, Fuzhou, Fuding and Gutian, but not Fu'an and Ningde,[97][103] and -t merged with -k in Chaozhou, Jieyang and Shantou.[101][42]

| Southern | Eastern | Northern | Central | Shao–Jiang | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| word | Proto-Min | Jieyang | Xiamen | Fuzhou | Fu'an | Jian'ou | Jianyang | Yong'an | Jiangle |

| 鴿 dove | *kəpD | kap7 | kap7 | kak7 | kap7 | kɔ7 | kɔ7 | kɯ7 | ko7 |

| 賊 thief | *dzhətD | tsʰak8 | tsʰat8 | tsʰaik8 | tsʰɛt8 | tsʰɛ6 | tʰe8 | tsʰa4 | tsʰa5 |

| 北 north | *pekD | pak7 | pak7 | poik7 | pœk7 | pɛ7 | pe7 | pa7 | pa3 |

| 劦 fit, agree | *ɣɑpD | haʔ8 | haʔ8 | hak8 | hap8 | xɔ6 | xɔ8 | haɯ4 | ho8 |

| 葛 dolichos | *kɑtD | kuaʔ7 | kuaʔ7 | kak7 | kat7 | kuɛ7 | kue7 | kuo7 | kuai7 |

| 客 guest | *khakD | kʰeʔ7 | kʰeʔ7 | kʰaʔ7 | kʰaʔ7 | kʰa7 | kʰa7 | kʰɔ7 | kʰa3 |

Vocabulary

Most Min vocabulary corresponds directly to cognates in other Chinese varieties, but there is also a significant number of distinctively Min words that may be traced back to proto-Min. In some cases a semantic shift has occurred in Min or the rest of Chinese:

- *tiaŋB 鼎 'wok'. The Min form preserves the original meaning 'cooking pot', but in other Chinese varieties this word (MC tengX > dǐng) has become specialized to refer to ancient ceremonial tripods.[34]

- *dzhənA 'rice field'. In Min this form has displaced the common Chinese term tián 田.[105][106] Many scholars identify the Min word with chéng 塍 (MC zying) 'raised path between fields', but Norman argues that it is cognate with céng 層 (MC dzong) 'additional layer or floor', reflecting the terraced fields commonly found in Fujian.[107]

- *tšhioC 厝 'house'.[108] Norman argues that the Min word is cognate with shù 戍 (MC syuH) 'to guard'.[109][8]

- *tshyiC 喙 'mouth'. In Min this form has displaced the common Chinese term kǒu 口.[87] It is believed to be cognate with huì 喙 (MC xjwojH) 'beak, bill, snout; to pant'.[8]

Norman and Mei Tsu-lin have suggested an Austroasiatic origin for some Min words:

- *-dəŋA 'shaman' may be compared with Vietnamese đồng (/ɗoŋ2/) 'to shamanize, to communicate with spirits' and Mon doŋ 'to dance (as if) under demonic possession'.[110][111] However, Laurent Sagart argues that this word is cognate with Chinese tóng 童 (MC duwng) 'child, servant'.[112]

- *kiɑnB 囝 'son' appears to be related to Vietnamese con (/kɔn/) and Mon kon 'child'.[91][113]

In other cases, the origin of the Min word is obscure. Such words include *khauA 骹 'foot',[114] *-tsiɑmB 䭕 'insipid'[98] and *dzyŋC 𧚔 'to wear'.[109]

Notes

- Southern Min varieties also have voiced stops and affricates, which are derived from earlier nasal initials.[42]

- The voiced initials in modern Southern Min varieties are derived from proto-Min nasal initials.[75]

- For Yong'an, Norman found only one example of a class *C word with a softened voiceless initial, having tone 2.[80]

- The only example of this final, *kiɑA 茄 "eggplant" (Xiamen kio2) is probably a relatively late loan from a Tai language.[85]

- This final is found only after coronal initials.[86]

- This final is found only after velar and glottal initials, and is distinguished from *i only in Southern Min.[87]

- Norman describes the reconstruction of this final as ad hoc, based on only two sets.[86]

- This final is found only after dental initials, and completely consistent examples are rare.[85]

- Norman describes the reconstruction of this final as ad hoc, based on only two sets.[88]

- This final is required to account for Southern Min developments, but few examples are attested across Min.[89]

- There are very few examples of *ot.[90]

- The sole example of *iɑt is found only in coastal Min.[91]

- Norman describes the reconstruction of this final as ad hoc, based on only two sets.[92]

- There are few examples of these finals.[93]

- This final is found only after velar initials, and the few examples of *yt are confined to the coastal dialects.[94]

- There are only two examples of this final, and none of *yat.[93]

- The reconstruction of this final is based on only two sets.[95]

References

- Norman (1988), pp. 210, 228.

- Norman (1988), pp. 54–55.

- Norman (1988), pp. 52–54.

- Norman (1988), p. 181.

- Norman (1988), pp. 191, 199–200, 204–205.

- Norman (1988), pp. 228–229.

- Ting (1983), pp. 9–10.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 33.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 79.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 76.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 388, n. 49.

- Norman (1988), pp. 211–214.

- Norman (1991b), pp. 334–336.

- Norman (1991b), pp. 335–336.

- Norman (1991b), p. 328.

- Norman (1988), p. 214.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 34–37.

- Norman (1991b), pp. 331–332.

- Sagart (2008), pp. 141–143.

- Norman (1991b), p. 336.

- Norman (1991b), p. 337.

- Kurpaska (2010), p. 49.

- Norman (1988), p. 233.

- Yan (2006), p. 121.

- Norman (1988), pp. 233–234.

- Kurpaska (2010), p. 52.

- Yan (2006), p. 122.

- Norman (1988), pp. 235, 241.

- Branner (1999), pp. 37, 78.

- Branner (2000), pp. 115–116.

- Handel (2010b), pp. 28–29.

- Norman (1974), p. 231.

- Norman (1974), pp. 28–30.

- Norman (1988), p. 231.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 102, 104, 108.

- Norman (1974), p. 28.

- Norman (1973), p. 231.

- Handel (2003), pp. 49–50.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 89.

- Handel (2010a).

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 84–93.

- Norman (1988), p. 237.

- Norman (1973), pp. 228–231.

- Norman (1973), pp. 229–231.

- Norman (1974), pp. 32–33.

- Norman (1986), pp. 380–382.

- Norman (1986), pp. 381–383.

- Norman (1986), p. 381.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 88–89.

- Norman (1973), pp. 224–227.

- Branner (1999), p. 40.

- Norman (1973), pp. 226–228.

- Norman (1974), pp. 33–35.

- Norman (1986), pp. 382–383.

- Norman (1988), pp. 229–230.

- Norman (1991b), pp. 340–341.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 88.

- Norman (1991a), pp. 207–208.

- Norman (1973), pp. 233–235.

- Norman (1988), pp. 230, 233.

- Norman (1991a), p. 212.

- Norman (1991a), p. 208.

- Norman (1991a), pp. 211–212.

- Bodman (1985), p. 16.

- Zheng (2016), pp. 84–92.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 46.

- Norman (1973), p. 233.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 171–173.

- Norman (1974), pp. 28–29.

- Norman (1974), pp. 32–35.

- Baxter (1992), pp. 210, 834.

- Zheng (2016), p. 119.

- Norman (1973), p. 223.

- Handel (2003), p. 49.

- Norman (1988), pp. 235–236.

- Handel (2003), pp. 55, 68–72.

- Norman (1973), pp. 226, 229, 232–233.

- Norman (1974), pp. 31–32.

- Handel (2003), pp. 58–59.

- Norman (1974), p. 32.

- Norman (1974), pp. 29–30.

- Norman (1974), p. 30.

- Norman (1981), p. 35.

- Norman (1981), pp. 35–36.

- Norman (1981), p. 48.

- Norman (1981), p. 50.

- Norman (1981), p. 41.

- Norman (1981), p. 51.

- Norman (1981), p. 54.

- Norman (1981), p. 59.

- Norman (1981), p. 63.

- Norman (1981), p. 64.

- Norman (1981), p. 65.

- Norman (1981), p. 57.

- Norman (1981), p. 71.

- Norman (1981), p. 36.

- Bodman (1985), p. 5.

- Norman (1981), p. 56.

- Norman (1988), p. 234.

- Bodman (1985), pp. 5–9.

- Bodman (1985), p. 7.

- Yan (2006), p. 136.

- Yan (2006), p. 138.

- Norman (1981), pp. 53–55, 58, 60, 66, 69.

- Norman (1981), p. 58.

- Norman (1988), pp. 231–232.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 59–60.

- Norman (1981), p. 47.

- Norman (1988), p. 232.

- Norman (1988), pp. 18–19.

- Norman & Mei (1976), pp. 296–297.

- Sagart (2008), p. 142.

- Norman & Mei (1976), pp. 297–298.

- Norman (1981), p. 44.

Works cited

- Baxter, William H. (1992), A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-012324-1.

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2014), Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- Bodman, Nicholas C. (1985), "The reflexes of initial nasals in Proto-Southern Min-Hingua", in Acson, Veneeta; Leed, Richard L. (eds.), For Gordon H. Fairbanks, Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 2–20, ISBN 978-0-8248-0992-8, JSTOR 20006706.

- Branner, David Prager (1999), "The classification of Longyan" (PDF), in Simmons, Richard VanNess (ed.), Issues in Chinese Dialect Description and Classification, Journal of Chinese Linguistics monograph series, pp. 36–83, JSTOR 23825676, OCLC 43076011.

- ——— (2000), Problems in Comparative Chinese Dialectology – the Classification of Miin and Hakka, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-015831-1.

- Handel, Zev (2003), "Northern Min tone values and the reconstruction of 'softened initials'" (PDF), Language and Linguistics, 4 (1): 47–84.

- ——— (2010a), "Old Chinese and Min", Chûgoku Gogaku, 257: 34–68.

- ——— (2010b), "Competing methodologies of Chinese dialect fieldwork, and their implications for the study of the history of the Northern Min dialects", in Coblin, Weldon South; Yue-Hashimoto, Anne O. (eds.), Studies in Honor of Jerry Norman, Hong Kong: Ng Tor-Tai Chinese Language Research Centre, Institute of Chinese Studies, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, pp. 13–39, ISBN 978-962-7330-21-9.

- Kurpaska, Maria (2010), Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism of "The Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects", Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-021914-2.

- Norman, Jerry (1973), "Tonal development in Min", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 1 (2): 222–238, JSTOR 23749795.

- ——— (1974), "The initials of Proto-Min", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 2 (1): 27–36, JSTOR 23749809.

- ——— (1981), "The Proto-Min finals", Proceedings of the International Conference on Sinology (Section on Linguistics and Paleography), Taipei: Academia Sinica, pp. 35–73, OCLC 9522150.

- ——— (1986), "The origin of Proto-Min softened stops", in McCoy, John; Light, Timothy (eds.), Contributions to Sino-Tibetan studies, Leiden: E. J. Brill, pp. 375–384, ISBN 978-90-04-07850-5.

- ——— (1988), Chinese, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- ——— (1991a), "Nasals in Old Southern Chinese", in Boltz, William G.; Shapiro, Michael C. (eds.), Studies in the Historical Phonology of Asian Languages, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 205–213, doi:10.1075/cilt.77.10nor, ISBN 978-90-272-3574-9.

- ——— (1991b), "The Mǐn dialects in historical perspective", in Wang, William S.-Y. (ed.), Languages and Dialects of China, Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series, Chinese University Press, pp. 325–360, JSTOR 23827042, OCLC 600555701.

- Norman, Jerry; Mei, Tsu-lin (1976), "The Austroasiatics in ancient South China: some lexical evidence" (PDF), Monumenta Serica, 32: 274–301, doi:10.1080/02549948.1976.11731121, JSTOR 40726203.

- Sagart, Laurent (2008), "The expansion of Setaria farmers in East Asia", in Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia; Blench, Roger; Ross, Malcolm D.; Peiros, Ilia; Lin, Marie (eds.), Past Human Migrations in East Asia: Matching Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics, Routledge, pp. 133–157, ISBN 978-0-415-39923-4.

- Ting, Pang-Hsin (1983), "Derivation time of colloquial Min from Archaic Chinese", Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, 54 (4): 1–14.

- Yan, Margaret Mian (2006), Introduction to Chinese Dialectology, LINCOM Europa, ISBN 978-3-89586-629-6.

- Zheng, Zhijun (2016), The Subgrouping of the Min Dialects (PhD thesis), City University of Hong Kong.

Further reading

- Mei, Tsu-lin (2015), "Shì shì "Yánshì jiāxùn" lǐ de 'nán rǎn wúyuè, běi zá yí lǔ' – jiān lùn xiàndài Mǐnyǔ de láiyuán" 試釋《顏氏家訓》裡的「南染吳越,北雜夷虜」 ──兼論現代閩語的來源 [The 'Wu dialect' of Southern dynasties and the origin of modern Min; plus an exegesis of Yan Zhitui's dictum, 'The South is tainted by Wu and Yue features, and the North is intermixed with barbaric tongues of Yi and Lu'] (PDF), Language and Linguistics (in Chinese), 16 (2): 119–138, doi:10.1177/1606822X14556607.

- Zheng, Zhijun (2018), "A new proposal for Min subgrouping based on a maximum-parsimony algorithm for generating phylogenetic trees", Lingua, 206: 67–84, doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2018.01.008.