Princeton University

Princeton University is a private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution.[8][lower-alpha 1] The institution moved to Newark in 1747, then to the current site nine years later. It was renamed to Princeton University in 1896.[13]

Princeton University shield | |

| Latin: Universitas Princetoniensis | |

Former names | College of New Jersey (1746–1896) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Dei Sub Numine Viget (Latin)[1] |

Motto in English | Under God's Power She Flourishes[1] |

| Type | Private |

| Established | January 18, 1746 |

Academic affiliations | AAU URA NAICU[2] |

| Endowment | $26.1 billion (2019)[3] |

| President | Christopher L. Eisgruber |

| Provost | Deborah Prentice |

Academic staff | 1,289[4] |

Administrative staff | 1,103 |

| Students | 8,374 (Fall 2018)[5] |

| Undergraduates | 5,428 (Fall 2018)[5] |

| Postgraduates | 2,946 (Fall 2018)[5] |

| Location | , , United States 40°20′43″N 74°39′22″W[6] |

| Campus | Suburban, college town 500 acres (2.0 km2) (Princeton)[1] |

| Colors | Orange and Black[7] |

| Nickname | Tigers |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division I Ivy League, ECAC Hockey, EARC, EIVA MAISA |

| Website | princeton |

| |

Princeton provides undergraduate and graduate instruction in the humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, and engineering.[14] It offers professional degrees through the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs, the School of Engineering and Applied Science, the School of Architecture and the Bendheim Center for Finance. The university also manages the Department of Energy's Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory. Princeton has the largest endowment per student in the United States.[15]

As of March 2020, 68 Nobel laureates, 15 Fields Medalists and 14 Turing Award laureates have been affiliated with Princeton University as alumni, faculty members or researchers. In addition, Princeton has been associated with 21 National Medal of Science winners, 5 Abel Prize winners, 5 National Humanities Medal recipients, 209 Rhodes Scholars, 139 Gates Cambridge Scholars and 126 Marshall Scholars.[16] Two U.S. Presidents, twelve U.S. Supreme Court Justices (three of whom currently serve on the court) and numerous living billionaires and foreign heads of state are all counted among Princeton's alumni body. Princeton has also graduated many prominent members of the U.S. Congress and the U.S. Cabinet, including eight Secretaries of State, three Secretaries of Defense and the current Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

History

New Light Presbyterians founded the College of New Jersey in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Its purpose was to train ministers.[17] The college was the educational and religious capital of Scottish Presbyterian America. In 1754, trustees of the College of New Jersey suggested that, in recognition of Governor Jonathan Belcher's interest, Princeton should be named as Belcher College. Belcher replied: "What a name that would be!"[18] In 1756, the college moved its campus to Princeton, New Jersey. Its home in Princeton was Nassau Hall, named for the royal House of Orange-Nassau of William III of England.

Following the untimely deaths of Princeton's first five presidents, John Witherspoon became president in 1768 and remained in that post until his death in 1794. During his presidency, Witherspoon shifted the college's focus from training ministers to preparing a new generation for secular leadership in the new American nation. To this end, he tightened academic standards and solicited investment in the college.[19] Witherspoon's presidency constituted a long period of stability for the college, interrupted by the American Revolution and particularly the Battle of Princeton, during which British soldiers briefly occupied Nassau Hall; American forces, led by George Washington, fired cannon on the building to rout them from it.

%2C_President_(1768-94).jpg)

In 1812, the eighth president of the College of New Jersey, Ashbel Green (1812–23), helped establish the Princeton Theological Seminary next door.[20] The plan to extend the theological curriculum met with "enthusiastic approval on the part of the authorities at the College of New Jersey."[21] Today, Princeton University and Princeton Theological Seminary maintain separate institutions with ties that include services such as cross-registration and mutual library access.[22][23]

Before the construction of Stanhope Hall in 1803, Nassau Hall was the college's sole building. The cornerstone of the building was laid on September 17, 1754.[24] During the summer of 1783, the Continental Congress met in Nassau Hall, making Princeton the country's capital for four months.[25] Over the centuries and through two redesigns following major fires (1802 and 1855), Nassau Hall's role shifted from an all-purpose building, comprising office, dormitory, library, and classroom space; to classroom space exclusively; to its present role as the administrative center of the University. The class of 1879 donated twin lion sculptures that flanked the entrance until 1911, when that same class replaced them with tigers.[26] Nassau Hall's bell rang after the hall's construction; however, the fire of 1802 melted it. The bell was then recast and melted again in the fire of 1855.[26]

James McCosh became the college's president in 1868 and lifted the institution out of a low period that had been brought about by the American Civil War.[27] During his two decades of service, he overhauled the curriculum, oversaw an expansion of inquiry into the sciences, and supervised the addition of a number of buildings in the High Victorian Gothic style to the campus.[27] McCosh Hall is named in his honor.[26]

In 1879, the first thesis for a Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) was submitted by James F. Williamson, Class of 1877.

In 1896, the college officially changed its name from the College of New Jersey to Princeton University to honor the town in which it resides.[28] During this year, the college also underwent large expansion and officially became a university. In 1900, the Graduate School was established.[29]

In 1902, Woodrow Wilson, graduate of the Class of 1879, was elected the 13th president of the university.[29] Under Wilson, Princeton introduced the preceptorial system in 1905, a then-unique concept in the United States that augmented the standard lecture method of teaching with a more personal form in which small groups of students, or precepts, could interact with a single instructor, or preceptor, in their field of interest.[30]

In 1906, the reservoir Lake Carnegie was created by Andrew Carnegie.[29] A collection of historical photographs of the building of the lake is housed at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library on Princeton's campus.[31] On October 2, 1913, the Princeton University Graduate College was dedicated.[29] In 1919 the School of Architecture was established.[29] In 1933, Albert Einstein became a lifetime member of the Institute for Advanced Study with an office on the Princeton campus. While always independent of the university, the Institute for Advanced Study occupied offices in Jones Hall for 6 years, from its opening in 1933, until its own campus was finished and opened in 1939. This helped start an incorrect impression that it was part of the university, one that has never been completely eradicated.

Coeducation at Princeton University

In 1969, Princeton University first admitted women as undergraduates. In 1887, the university actually maintained and staffed a sister college, Evelyn College for Women, in the town of Princeton on Evelyn and Nassau streets. It was closed after roughly a decade of operation. After abortive discussions with Sarah Lawrence College to relocate the women's college to Princeton and merge it with the University in 1967, the administration decided to admit women and turned to the issue of transforming the school's operations and facilities into a female-friendly campus. The administration had barely finished these plans in April 1969 when the admissions office began mailing out its acceptance letters. Its five-year coeducation plan provided $7.8 million for the development of new facilities that would eventually house and educate 650 women students at Princeton by 1974. Ultimately, 148 women, consisting of 100 freshmen and transfer students of other years, entered Princeton on September 6, 1969 amidst much media attention. Princeton enrolled its first female graduate student, Sabra Follett Meservey, as a PhD candidate in Turkish history in 1961. A handful of undergraduate women had studied at Princeton from 1963 on, spending their junior year there to study "critical languages" in which Princeton's offerings surpassed those of their home institutions. They were considered regular students for their year on campus, but were not candidates for a Princeton degree.

As a result of a 1979 lawsuit by Sally Frank, Princeton's eating clubs were required to go coeducational in 1991, after Tiger Inn's appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was denied.[32] In 1987, the university changed the gendered lyrics of "Old Nassau" to reflect the school's co-educational student body.[33] From 2009–2011, Princeton professor Nannerl O. Keohane chaired a committee on undergraduate women's leadership at the university, appointed by President Shirley M. Tilghman.[34]

Princeton and slavery

In 2017, Princeton University unveiled a large-scale public history and digital humanities investigation into its historical involvement with slavery, following slavery studies produced by other institutions of higher education such as Brown University and Georgetown University.[36][37][38] The Princeton & Slavery Project began in 2013, when history professor Martha A. Sandweiss and a team of undergraduate and graduate students started researching topics such as the slaveholding practices of Princeton's early presidents and trustees, the southern origins of a large proportion of Princeton students during the 18th and 19th centuries, and racial violence in Princeton during the antebellum period.[39][40]

The Princeton & Slavery Project published its findings online in November 2017, on a website that included more than 80 scholarly essays and a digital archive of hundreds of primary sources.[36][37] The website launched in conjunction with a scholarly conference, the premiere of seven short plays based on project findings and commissioned by the McCarter Theatre, and a public art installation by American artist Titus Kaphar commemorating a slave sale that took place at the historic President's House in 1766.[41][42]

In April 2018, university trustees announced that they would name two public spaces for James Collins Johnson and Betsey Stockton, enslaved people who lived and worked on Princeton's campus and whose stories were publicized by the Princeton & Slavery Project.[43][44] The project has also served as a model for institutional slavery studies at the Princeton Theological Seminary and Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.[45][46]

Campus

.jpg)

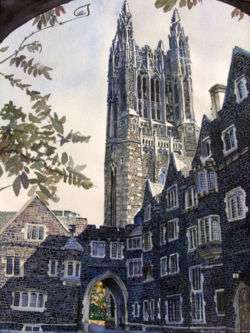

The main campus sits on about 500 acres (2.0 km2) in Princeton. In 2011, the main campus was named by Travel+Leisure as one of the most beautiful in the United States.[47] The James Forrestal Campus is split between nearby Plainsboro and South Brunswick. The University also owns some property in West Windsor Township.[1]:44 The campuses are situated about one hour from both New York City and Philadelphia.

The first building on campus was Nassau Hall, completed in 1756 and situated on the northern edge of campus facing Nassau Street.[26] The campus expanded steadily around Nassau Hall during the early and middle 19th century.[48][49] The McCosh presidency (1868–88) saw the construction of a number of buildings in the High Victorian Gothic and Romanesque Revival styles; many of them are now gone, leaving the remaining few to appear out of place.[50] At the end of the 19th century much of Princeton's architecture was designed by the Cope and Stewardson firm (same architects who designed a large part of Washington University in St. Louis and University of Pennsylvania) resulting in the Collegiate Gothic style for which it is known today.[51] Implemented initially by William Appleton Potter[51] and later enforced by the University's supervising architect, Ralph Adams Cram,[52] the Collegiate Gothic style remained the standard for all new building on the Princeton campus through 1960.[53][54] A flurry of construction in the 1960s produced a number of new buildings on the south side of the main campus, many of which have been poorly received.[55] Several prominent architects have contributed some more recent additions, including Frank Gehry (Lewis Library),[56] I. M. Pei (Spelman Halls),[57] Demetri Porphyrios (Whitman College, a Collegiate Gothic project),[58] Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown (Frist Campus Center, among several others),[59] and Rafael Viñoly (Carl Icahn Laboratory).[60]

A group of 20th-century sculptures scattered throughout the campus forms the Putnam Collection of Sculpture. It includes works by Alexander Calder (Five Disks: One Empty), Jacob Epstein (Albert Einstein), Henry Moore (Oval with Points), Isamu Noguchi (White Sun), and Pablo Picasso (Head of a Woman).[61] Richard Serra's The Hedgehog and The Fox is located between Peyton and Fine halls next to Princeton Stadium and the Lewis Library.[62]

At the southern edge of the campus is Lake Carnegie, an artificial lake named for Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie financed the lake's construction in 1906 at the behest of a friend who was a Princeton alumnus.[63] Carnegie hoped the opportunity to take up rowing would inspire Princeton students to forsake football, which he considered "not gentlemanly."[64] The Shea Rowing Center on the lake's shore continues to serve as the headquarters for Princeton rowing.[65]

Cannon Green

Buried in the ground at the center of the lawn south of Nassau Hall is the "Big Cannon," which was left in Princeton by British troops as they fled following the Battle of Princeton. It remained in Princeton until the War of 1812, when it was taken to New Brunswick.[66] In 1836 the cannon was returned to Princeton and placed at the eastern end of town. It was removed to the campus under cover of night by Princeton students in 1838 and buried in its current location in 1840.[67]

A second "Little Cannon" is buried in the lawn in front of nearby Whig Hall. This cannon, which may also have been captured in the Battle of Princeton, was stolen by students of Rutgers University in 1875. The theft ignited the Rutgers-Princeton Cannon War. A compromise between the presidents of Princeton and Rutgers ended the war and forced the return of the Little Cannon to Princeton.[68] The protruding cannons are occasionally painted scarlet by Rutgers students who continue the traditional dispute.[69][70][71]

In years when the Princeton football team beats the teams of both Harvard University and Yale University in the same season, Princeton celebrates with a bonfire on Cannon Green. This occurred in 2012, ending a five-year drought. The next bonfire happened on November 24, 2013, and was broadcast live over the Internet.[72]

Landscape

Princeton's grounds were designed by Beatrix Farrand between 1912 and 1943. Her contributions were most recently recognized with the naming of a courtyard for her.[73] Subsequent changes to the landscape were introduced by Quennell Rothschild & Partners in 2000. In 2005, Michael Van Valkenburgh was hired as the new consulting landscape architect for the campus.[74] Lynden B. Miller was invited to work with him as Princeton's consulting gardening architect, focusing on the 17 gardens that are distributed throughout the campus.[75]

Buildings

Nassau Hall

Nassau Hall is the oldest building on campus. Begun in 1754 and completed in 1756,[26] it was the first seat of the New Jersey Legislature in 1776,[76] was involved in the battle of Princeton in 1777,[26] and was the seat of the Congress of the Confederation (and thus capitol of the United States) from June 30, 1783, to November 4, 1783.[77][78] It now houses the office of the university president and other administrative offices, and remains the symbolic center of the campus.[79] The front entrance is flanked by two bronze tigers, a gift of the Princeton Class of 1879.[26] Commencement is held on the front lawn of Nassau Hall in good weather.[80] In 1966, Nassau Hall was added to the National Register of Historic Places.[81]

Residential colleges

.jpg)

Princeton has six undergraduate residential colleges, each housing approximately 500 freshmen, sophomores, some juniors and seniors, and a handful of junior and senior resident advisers. Each college consists of a set of dormitories, a dining hall, a variety of other amenities—such as study spaces, libraries, performance spaces, and darkrooms—and a collection of administrators and associated faculty. Two colleges, First College and Forbes College (formerly Woodrow Wilson College and Princeton Inn College, respectively), date to the 1970s; three others, Rockefeller, Mathey, and Butler Colleges, were created in 1983 following the Committee on Undergraduate Residential Life (CURL) report, which suggested the institution of residential colleges as a solution to an allegedly fragmented campus social life. The construction of Whitman College, the university's sixth residential college, was completed in 2007.[82]

Rockefeller and Mathey are located in the northwest corner of the campus; Princeton brochures often feature their Collegiate Gothic architecture. Like most of Princeton's Gothic buildings, they predate the residential college system and were fashioned into colleges from individual dormitories.[83][84]

Wilson and Butler, located south of the center of the campus, were built in the 1960s. Wilson served as an early experiment in the establishment of the residential college system. Butler, like Rockefeller and Mathey, consisted of a collection of ordinary dorms (called the "New New Quad") before the addition of a dining hall made it a residential college. Widely disliked for their edgy modernist design, including "waffle ceilings," the dormitories on the Butler Quad were demolished in 2007. Butler is now reopened as a four-year residential college, housing both under- and upperclassmen.[85]

Forbes is located on the site of the historic Princeton Inn, a gracious hotel overlooking the Princeton golf course. The Princeton Inn, originally constructed in 1924, played regular host to important symposia and gatherings of renowned scholars from both the university and the nearby Institute for Advanced Study for many years.[86] Forbes currently houses nearly 500 undergraduates in its residential halls.[87]

In 2003, Princeton broke ground for a sixth college named Whitman College after its principal sponsor, Meg Whitman, who graduated from Princeton in 1977. The new dormitories were constructed in the Collegiate Gothic architectural style and were designed by architect Demetri Porphyrios. Construction finished in 2007, and Whitman College was inaugurated as Princeton's sixth residential college that same year.[88]

The precursor of the present college system in America was originally proposed by university president Woodrow Wilson in the early 20th century. For over 800 years, however, the collegiate system had already existed in Britain at Cambridge and Oxford Universities. Wilson's model was much closer to Yale's present system, which features four-year colleges. Lacking the support of the trustees, the plan languished until 1968. That year, Wilson College was established to cap a series of alternatives to the eating clubs. Fierce debates raged before the present residential college system emerged. The plan was first attempted at Yale, but the administration was initially uninterested; an exasperated alumnus, Edward Harkness, finally paid to have the college system implemented at Harvard in the 1920s, leading to the oft-quoted aphorism that the college system is a Princeton idea that was executed at Harvard with funding from Yale.[89]

Princeton has one graduate residential college, known simply as the Graduate College, located beyond Forbes College at the outskirts of campus. The far-flung location of the GC was the spoil of a squabble between Woodrow Wilson and then-Graduate School Dean Andrew Fleming West. Wilson preferred a central location for the College; West wanted the graduate students as far as possible from the campus. Ultimately, West prevailed.[86] The Graduate College is composed of a large Collegiate Gothic section crowned by Cleveland Tower, a local landmark that also houses a world-class carillon. The attached New Graduate College provides a modern contrast in architectural style.[90]

McCarter Theatre

The Tony-award-winning[91] McCarter Theatre was built by the Princeton Triangle Club, a student performance group, using club profits and a gift from Princeton University alumnus Thomas McCarter. Today, the Triangle Club performs its annual freshmen revue, fall show, and Reunions performances in McCarter. McCarter is also recognized as one of the leading regional theaters in the United States.

Art Museum

The Princeton University Art Museum was established in 1882 to give students direct, intimate, and sustained access to original works of art that complement and enrich instruction and research at the university. This continues to be a primary function, along with serving as a community resource and a destination for national and international visitors.

Numbering over 92,000 objects, the collections range from ancient to contemporary art and concentrate geographically on the Mediterranean regions, Western Europe, China, the United States, and Latin America. There is a collection of Greek and Roman antiquities, including ceramics, marbles, bronzes, and Roman mosaics from faculty excavations in Antioch. Medieval Europe is represented by sculpture, metalwork, and stained glass. The collection of Western European paintings includes examples from the early Renaissance through the 19th century, with masterpieces by Monet,[92][93][94] Cézanne,[95] and Van Gogh,[96] and features a growing collection of 20th-century and contemporary art, including iconic paintings such as Andy Warhol's Blue Marilyn.[97]

One of the best features of the museums is its collection of Chinese art, with important holdings in bronzes, tomb figurines, painting, and calligraphy. Its collection of pre-Columbian art includes examples of Mayan art, and is commonly considered to be the most important collection of pre-Columbian art outside of Latin America. The museum has collections of old master prints and drawings and a comprehensive collection of over 27,000 original photographs. African art and Northwest Coast Indian art are also represented. The Museum also oversees the outdoor Putnam Collection of Sculpture.

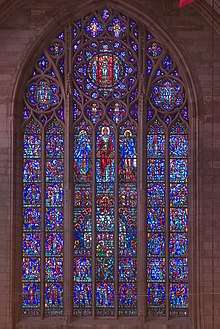

University Chapel

The Princeton University Chapel is located on the north side of campus, near Nassau Street. It was built between 1924 and 1928, at a cost of $2.3 million,[98] approximately $34.2 million in 2019 dollars. Ralph Adams Cram, the University's supervising architect, designed the Chapel, which he viewed as the crown jewel for the Collegiate Gothic motif he had championed for the campus.[99] At the time of its construction, it was the second largest university chapel in the world, after King's College Chapel, Cambridge.[100] It underwent a two-year, $10 million restoration campaign between 2000 and 2002.[101]

Measured on the exterior, the Chapel is 277 feet (84 m) long, 76 feet (23 m) wide at its transepts, and 121 feet (37 m) high.[102] The exterior is Pennsylvania sandstone, with Indiana limestone used for the trim.[103] The interior is mostly limestone and Aquia Creek sandstone. The design evokes an English church of the Middle Ages.[104] The extensive iconography, in stained glass, stonework, and wood carvings, has the common theme of connecting religion and scholarship.[99]

The Chapel seats almost 2,000.[105][106] It hosts weekly ecumenical Christian services,[107] daily Roman Catholic mass,[108][109] and several annual special events.

Murray-Dodge Hall

Murray-Dodge Hall houses the Office of Religious Life (ORL),[110] the Murray Dodge Theater, the Murray-Dodge Café,[111] the Muslim Prayer Room and the Interfaith Prayer Room.[112] The ORL houses the office of the Dean of Religious Life, Alison Boden,[113] and a number of university chaplains, including the country's first Hindu chaplain, Vineet Chander; and one of the country's first Muslim chaplains, Sohaib Sultan.[114]

Apartment facilities

Princeton university has several apartment facilities for graduate students and their dependents. They are Lakeside Apartments, Lawrence Apartments, and Stanworth Apartments.[115]

Sustainability

Published in 2008, Princeton's Sustainability Plan highlights three priority areas for the University's Office of Sustainability: reduction of greenhouse gas emissions; conservation of resources; and research, education, and civic engagement.[116] Princeton has committed to reducing its carbon dioxide emissions to 1990 levels by 2020,[117]:Energy without the purchase of offsets.[118] The University published its first Sustainability Progress Report in November 2009.[119] The University has adopted a green purchasing policy and recycling program that focuses on paper products, construction materials, lightbulbs, furniture, and electronics.[117]:Purchasing[120] Its dining halls have set a goal to purchase 75% sustainable food products by 2015.[117]:Food The student organization "Greening Princeton" seeks to encourage the University administration to adopt environmentally friendly policies on campus.[121]

Organization

The Trustees of Princeton University, a 40-member board, is responsible for the overall direction of the University. It approves the operating and capital budgets, supervises the investment of the University's endowment and oversees campus real estate and long-range physical planning. The trustees also exercise prior review and approval concerning changes in major policies, such as those in instructional programs and admission, as well as tuition and fees and the hiring of faculty members.

With an endowment of $26.1 billion, Princeton University is among the wealthiest universities in the world.[122] Ranked in 2010 as the third largest endowment in the United States, the university had the greatest per-student endowment in the world (over $2 million for undergraduates) in 2011.[123] Such a significant endowment is sustained through the continued donations of its alumni and is maintained by investment advisers.[124] Some of Princeton's wealth is invested in its art museum, which features works by Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Jackson Pollock, and Andy Warhol among other prominent artists.

Academics

Undergraduates fulfill general education requirements, choose among a wide variety of elective courses, and pursue departmental concentrations and interdisciplinary certificate programs. Required independent work is a hallmark of undergraduate education at Princeton. Students graduate with either the Bachelor of Arts (A.B.) or the Bachelor of Science in Engineering (B.S.E.).

The graduate school offers advanced degrees spanning the humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, and engineering. Doctoral education is available in most disciplines.[125] It emphasizes original and independent scholarship whereas master's degree programs in architecture, engineering, finance, and public affairs and public policy prepare candidates for careers in public life and professional practice.

The university has ties with the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton Theological Seminary and the Westminster Choir College of Rider University.[lower-alpha 2]

Undergraduate

.jpg)

Undergraduate courses in the humanities are traditionally either seminars or lectures held 2 or 3 times a week with an additional discussion seminar that is called a "precept." To graduate, all A.B. candidates must complete a senior thesis and, in most departments, one or two extensive pieces of independent research that are known as "junior papers." Juniors in some departments, including architecture and the creative arts, complete independent projects that differ from written research papers. A.B. candidates must also fulfill a three or four semester foreign language requirement and distribution requirements (which include, for example, classes in ethics, literature and the arts, and historical analysis) with a total of 31 classes. B.S.E. candidates follow a parallel track with an emphasis on a rigorous science and math curriculum, a computer science requirement, and at least two semesters of independent research including an optional senior thesis. All B.S.E. students must complete at least 36 classes. A.B. candidates typically have more freedom in course selection than B.S.E. candidates because of the fewer number of required classes. Nonetheless, in the spirit of a liberal arts education, both enjoy a comparatively high degree of latitude in creating a self-structured curriculum.

Undergraduates agree to adhere to an academic integrity policy called the Honor Code, established in 1893. Under the Honor Code, faculty do not proctor examinations; instead, the students proctor one another and must report any suspected violation to an Honor Committee made up of undergraduates. The Committee investigates reported violations and holds a hearing if it is warranted. An acquittal at such a hearing results in the destruction of all records of the hearing; a conviction results in the student's suspension or expulsion.[126] The signed pledge required by the Honor Code is so integral to students' academic experience that the Princeton Triangle Club performs a song about it each fall.[127][128] Out-of-class exercises fall under the jurisdiction of the Faculty-Student Committee on Discipline.[129] Undergraduates are expected to sign a pledge on their written work affirming that they have not plagiarized the work.[130]

Admissions and financial aid

| 2017[131] | 2016[132] | 2015[133] | 2014[134] | 2013[135] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applicants | 31,056 | 29,303 | 27,290 | 26,641 | 26,498 |

| Admits | 1,990 | 1,911 | 1,948 | 1,983 | 1,963 |

| Admit rate | 6.4% | 6.5% | 7.1% | 7.4% | 7.4% |

| Enrolled | 1,306 | 1,306 | 1,319 | 1,312 | 1,285 |

| SAT range | 1430–1570 | 2100–2380 | 2100–2380 | 2100–2400 | 2120–2390 |

| ACT range | 31–35 | 32–35 | 32–35 | 31–35 | 31–35 |

Princeton's undergraduate program is highly selective, admitting 6.4% of undergraduate applicants in the 2016–2017 admissions cycle (for the Class of 2021).[131] The middle 50% range of SAT scores was 1430–1570 and the middle 50% range of the ACT composite score was 31–35.[131]

In September 2006, the university announced that all applicants for the Class of 2012 would be considered in a single pool, effectively ending the school's early decision program.[136] In February 2011, following decisions by the University of Virginia and Harvard University to reinstate their early admissions programs, Princeton announced it would institute an early action program, starting with applicants for the Class of 2016.[137] In 2011, The Business Journal rated Princeton as the most selective college in the Eastern United States.[138]

In 2001, expanding on earlier reforms, Princeton became the first university to eliminate the use of loans in financial aid, replacing them with grants.[139] In addition, all admissions are need-blind.[140] Kiplinger magazine in 2016 ranked Princeton as the best value among private universities, noting that the average graduating debt is $8,557.[141]

Grade deflation policy

In 2004, Nancy Weiss Malkiel, the Dean of the College, implemented a grade deflation policy to curb the number of A-range grades undergraduates received.[142] Malkiel's argument was that an A was beginning to lose its meaning as a larger percentage of the student body received them.[142] While the number of A's has indeed decreased under the policy, many argue that this is hurting Princeton students when they apply to jobs or graduate school.[142] Malkiel has said that she sent pamphlets to inform institutions about the policy so that they consider Princeton students equally,[142] but students argue that Princeton graduates can apply to other institutions that know nothing about it. They argue further that as other schools purposefully inflate their grades,[143] Princeton students' GPAs will look low by comparison. Further, studies have shown that employers prefer high grades even when they are inflated.[144] The policy remained in place even after Malkiel stepped down at the end of the 2010–2011 academic term. The policy deflates grades only relative to their previous levels; indeed, as of 2009, or five years after the policy was instituted, the average graduating GPA saw a marginal decrease, from 3.46 to 3.39.[145]

In August 2014, a faculty committee tasked by Dean of the College Valerie Smith to review the effectiveness of grade deflation found not only that the 35% target was both often misinterpreted as a hard quota and applied inconsistently across departments, but also that grades had begun to decline in 2003, the year before the policy was implemented.[146][147] The committee concluded that the observed lower grades since 2003 were the result of discussions and increased awareness during and since the implementation of the deflation policy, and not the deflation targets themselves, so recommended removing the numerical targets while charging individual departments with developing consistent standards for grading.[148] In October 2014, following a faculty vote, the numerical targets were removed as recommended by the committee.[149]

Graduate

The Graduate School has about 2,600 students in 42 academic departments and programs in social sciences, engineering, natural sciences, and humanities. These departments include the Department of Psychology, Department of History, and Department of Economics.

In 2017–2018, it received nearly 11,000 applications for admission and accepted around 1,000 applicants.[150] The University also awarded 319 Ph.D. degrees and 170 final master's degrees. Princeton has no medical school, law school, business school, or school of education. (A short-lived Princeton Law School folded in 1852.) It offers professional graduate degrees in architecture, engineering, finance, and public policy, the last through the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs, founded in 1930 as the School of Public and International Affairs, renamed in 1948 after university president (and U.S. President) Woodrow Wilson, and most recently renamed in 2020.

Libraries

The Princeton University Library system houses over eleven million holdings[151] including seven million bound volumes.[152] The main university library, Firestone Library, which houses almost four million volumes, is one of the largest university libraries in the world.[153] Additionally, it is among the largest "open stack" libraries in existence. Its collections include the autographed manuscript of F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby and George F. Kennan's Long Telegram. In addition to Firestone library, specialized libraries exist for architecture, art and archaeology, East Asian studies, engineering, music, public and international affairs, public policy and university archives, and the sciences. In an effort to expand access, these libraries also subscribe to thousands of electronic resources. In February 2007, Princeton became the 12th major library system to join Google's ambitious project to scan the world's great literary works and make them searchable over the Web.[154]

Rankings

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| ARWU[155] | 5 |

| Forbes[156] | 5 |

| THE/WSJ[157] | 5 |

| U.S. News & World Report[158] | 1 |

| Washington Monthly[159] | 8 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[160] | 6 |

| QS[161] | 12 |

| THE[162] | 6 |

| U.S. News & World Report[163] | 8 |

|

USNWR graduate school rankings[164] | |

|---|---|

| Engineering | 17 |

|

USNWR departmental rankings[164] | |

|---|---|

| Biological Sciences | 6 |

| Chemistry | 9 |

| Computer Science | 8 |

| Earth Sciences | 10 |

| Economics | 1 |

| English | 8 |

| History | 1 |

| Mathematics | 1 |

| Physics | 3 |

| Political Science | 3 |

| Psychology | 8 |

| Public Affairs | 10 |

| Sociology | 1 |

From 2001 through 2019, Princeton University was ranked either first or second among national universities by U.S. News & World Report, holding the top spot for 17 of those 19 years[165] (sole #1 twelve times, tied with Harvard for #1 five times). Princeton was ranked first in the 2019 U.S. News rankings. Princeton also was ranked #1 in the 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019 rankings for "best undergraduate teaching."[166] In the 2020 Times Higher Education assessment of the world's greatest universities, Princeton was ranked 6th.[167] In the 2020 QS World University Rankings, it was ranked 13th overall in the world.[168]

In the 2015 U.S. News & World Report "Graduate School Rankings," all thirteen of Princeton's doctoral programs evaluated were ranked in their respective top 20, 8 of them in the top 5, and 4 of them in the top spot (Economics, History, Mathematics, Sociology).[166]

Princeton was ranked 6th among 300 Best World Universities in 2018 compiled by Human Resources & Labor Review (HRLR).[169]

Princeton University has an IBM BlueGeneL supercomputer, called Orangena, which was ranked as the 89th fastest computer in the world in 2005 (LINPACK performance of 4713 compared to 12250 for other U.S. universities and 280600 for the top-ranked supercomputer, belonging to the U.S. Department of Energy).[170]

Institutes

- Princeton Environmental Institute

The Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI) is an "interdisciplinary center of environmental research, education, and outreach" at the university.[171][172][173] PEI was started in 1994.[171][173] About 90 faculty members at Princeton University are affiliated with it.[174]

The Princeton Environmental Institute has the following research centers:[175]

- Carbon Mitigation Initiative (CMI): This is a 15-year-long partnership between PEI and British Petroleum with the goal of finding solutions to problems related to climate change.[175][176] The Stabilization Wedge Game has been created as part of this initiative.[177]

- Center for BioComplexity (CBC)[175][178]

- Cooperative Institute for Climate Science (CICS): This is a collaboration with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory.[175][179]

- Energy Systems Analysis Group[175][180]

- Grand Challenges[175][181]

Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory

The Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, PPPL, was founded in 1951 as Project Matterhorn, a top secret cold war project aimed at achieving controlled nuclear fusion. Princeton astrophysics professor Lyman Spitzer became the first director of the project and remained director until the lab’s declassification in 1961 when it received its current name.[182]

PPPL currently houses approximately half of the graduate astrophysics department, the Princeton Program in Plasma Physics. The lab is also home to the Harold P. Furth Plasma Physics Library. The library contains all declassified Project Matterhorn documents, included the first design sketch of a stellarator by Lyman Spitzer.[183] For the 2018-19 academic year, the university allocated approximately 30% of its research expenditures or 5% of its total budget, over 100 million dollars, to PPPL.[184]

Princeton is one of five US universities to operate a Department of Energy national laboratory.

Student life and culture

University housing is guaranteed to all undergraduates for all four years. More than 98% of students live on campus in dormitories.[185] Freshmen and sophomores must live in residential colleges, while juniors and seniors typically live in designated upperclassman dormitories. The actual dormitories are comparable, but only residential colleges have dining halls. Nonetheless, any undergraduate may purchase a meal plan and eat in a residential college dining hall. Recently, upperclassmen have been given the option of remaining in their college for all four years. Juniors and seniors also have the option of living off-campus, but high rent in the Princeton area encourages almost all students to live in university housing. Undergraduate social life revolves around the residential colleges and a number of coeducational eating clubs, which students may choose to join in the spring of their sophomore year. Eating clubs, which are not officially affiliated with the university, serve as dining halls and communal spaces for their members and also host social events throughout the academic year.[186]

Princeton's six residential colleges host a variety of social events and activities, guest speakers, and trips. The residential colleges also sponsor trips to New York for undergraduates to see ballets, operas, Broadway shows, sports events, and other activities. The eating clubs, located on Prospect Avenue, are co-ed organizations for upperclassmen. Most upperclassmen eat their meals at one of the eleven eating clubs. Additionally, the clubs serve as evening and weekend social venues for members and guests.[187] The eleven clubs are Cannon, Cap and Gown, Charter, Cloister, Colonial, Cottage, Ivy, Quadrangle, Terrace, Tiger, and Tower.[188]

Princeton hosts two Model United Nations conferences, PMUNC[189] in the fall for high school students and PDI[190] in the spring for college students. It also hosts the Princeton Invitational Speech and Debate tournament each year at the end of November. Princeton also runs Princeton Model Congress, an event that is held once a year in mid-November. The four-day conference has high school students from around the country as participants.[191]

Although the school's admissions policy is need-blind, Princeton, based on the proportion of students who receive Pell Grants, was ranked as a school with little economic diversity among all national universities ranked by U.S. News & World Report.[192] While Pell figures are widely used as a gauge of the number of low-income undergraduates on a given campus, the rankings article cautions "the proportion of students on Pell Grants isn't a perfect measure of an institution's efforts to achieve economic diversity," but goes on to say that "still, many experts say that Pell figures are the best available gauge of how many low-income undergrads there are on a given campus."[193]

TigerTrends is a university-based student run fashion, arts, and lifestyle magazine.[194]

Demographics

Princeton has made significant progress in expanding the diversity of its student body in recent years. The 2016 freshman class was the most diverse in the school's history, with over 43% of students identifying as students of color.[195] Undergraduate and master's students were 51% male and 49% female for the 2018–19 academic year.[196]

The median family income of Princeton students is $186,100, with 57% of students coming from the top 10% highest-earning families and 14% from the bottom 60%.[197]

In 1999, 10% of the student body was Jewish, a percentage lower than those at other Ivy League schools. Sixteen percent of the student body was Jewish in 1985; the number decreased by 40% from 1985 to 1999. This decline prompted The Daily Princetonian to write a series of articles on the decline and its reasons. Caroline C. Pam of The New York Observer wrote that Princeton was "long dogged by a reputation for anti-Semitism" and that this history as well as Princeton's elite status caused the university and its community to feel sensitivity towards the decrease of Jewish students.[198] At the time many Jewish students at Princeton dated Jewish students at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia because they perceived Princeton as an environment where it was difficult to find romantic prospects; Pam stated that there was a theory that the dating issues were a cause of the decline in Jewish students.[198]

In 1981, the population of African Americans at Princeton University made up less than 10%. Bruce M. Wright was admitted into the university in 1936 as the first African American, however, his admission was a mistake and when he got to campus he was asked to leave. Three years later Wright asked the dean for an explanation on his dismissal and the dean suggested to him that "a member of your race might feel very much alone" at Princeton University.[199]

Traditions

..jpg)

- Arch Sings – Late-night concerts that feature one or several of Princeton's undergraduate a cappella groups, such as the Princeton Nassoons, Princeton Tigertones, Princeton Footnotes, Princeton Roaring 20, and The Princeton Wildcats. The free concerts take place in one of the larger arches on campus. Most are held in Blair Arch or Class of 1879 Arch.

- Bonfire – Ceremonial bonfire that takes place in Cannon Green behind Nassau Hall. It is held only if Princeton beats both Harvard University and Yale University at football in the same season. The most recent bonfire was lighted on November 18, 2018.[200]

- Bicker – Selection process for new members that is employed by selective eating clubs. Prospective members, or bickerees, are required to perform a variety of activities at the request of current members.[201]

- Cane Spree – An athletic competition between freshmen and sophomores that is held in the fall. The event centers on cane wrestling, where a freshman and a sophomore will grapple for control of a cane. This commemorates a time in the 1870s when sophomores, angry with the freshmen who strutted around with fancy canes, stole all of the canes from the freshmen, hitting them with their own canes in the process.[202]

- The Clapper or Clapper Theft – The act of climbing to the top of Nassau Hall to steal the bell clapper, which rings to signal the start of classes on the first day of the school year. For safety reasons, the clapper has been removed permanently.

- Class Jackets (Beer Jackets) – Each graduating class designs a Class Jacket that features its class year. The artwork is almost invariably dominated by the school colors and tiger motifs.

- Communiversity – An annual street fair with performances, arts and crafts, and other activities that attempts to foster interaction between the university community and the residents of Princeton.

- Dean's Date – The Tuesday at the end of each semester when all written work is due. This day signals the end of reading period and the beginning of final examinations. Traditionally, undergraduates gather outside McCosh Hall before the 5:00 PM deadline to cheer on fellow students who have left their work to the very last minute.[203]

- FitzRandolph Gates – At the end of Princeton's graduation ceremony, the new graduates process out through the main gate of the university as a symbol of the fact that they are leaving college. According to tradition, anyone who exits campus through the FitzRandolph Gates before his or her own graduation date will not graduate.[204][205]

- Holder Howl – The midnight before Dean's Date, students from Holder Hall and elsewhere gather in the Holder courtyard and take part in a minute-long, communal primal scream to vent frustration from studying with impromptu, late night noise making.[206]

- Houseparties – Formal parties that are held simultaneously by all of the eating clubs at the end of the spring term.

- Ivy stones - Class memorial stones placed on the exterior walls of academic buildings around the campus.

- Lawnparties – Parties that feature live bands that are held simultaneously by all of the eating clubs at the start of classes and at the conclusion of the academic year.

- Princeton Locomotive – Chant traditionally used by Princetonians to acknowledge a particular year or class. It goes: "HIP!! HIP!! Rah! Rah! Rah! TIGER! TIGER! TIGER! SIS! SIS! SIS! BOOM! BOOM! BOOM! Bahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh PRINCETON! PRINCETON! PRINCETON!"[207] Following it are three chants of the class that is being acknowledged. It is commonly heard at Opening Exercises in the fall as alumni and current students welcome the freshman class, as well as the P-rade in the spring at Princeton Reunions.

- Newman's Day – Students attempt to drink 24 beers in the 24 hours of April 24. According to The New York Times, "the day got its name from an apocryphal quote attributed to Paul Newman: '24 beers in a case, 24 hours in a day. Coincidence? I think not.'"[208] Newman had spoken out against the tradition, however.[209]

- Nude Olympics – Annual nude and partially nude frolic in Holder Courtyard that takes place during the first snow of the winter. Started in the early 1970s, the Nude Olympics went co-educational in 1979 and gained much notoriety with the American press. For safety reasons, the administration banned the Olympics in 2000 to the chagrin of students.[210][211]

- Prospect 11 – The act of drinking a beer at all 11 eating clubs in a single night.

- P-rade – Traditional parade of alumni and their families. They process through campus by class year during Reunions.[212]

- Reunions – Massive annual gathering of alumni held the weekend before graduation.

Athletics

Princeton supports organized athletics at three levels: varsity intercollegiate, club intercollegiate, and intramural. It also provides "a variety of physical education and recreational programs" for members of the Princeton community. According to the athletics program's mission statement, Princeton aims for its students who participate in athletics to be "'student athletes' in the fullest sense of the phrase."[213] Most undergraduates participate in athletics at some level.[214]

Princeton's colors are orange and black. The school's athletes are known as Tigers, and the mascot is a tiger. The Princeton administration considered naming the mascot in 2007, but the effort was dropped in the face of alumni opposition.[215]

Varsity

Princeton is an NCAA Division I school. Its athletic conference is the Ivy League. Princeton hosts 38 men's and women's varsity sports.[214] The largest varsity sport is rowing, with almost 150 athletes.[65]

Princeton's football team has a long and storied history. Princeton played against Rutgers University in the first intercollegiate football game in the U.S. on Nov 6, 1869. By a score of 6–4, Rutgers won the game, which was played by rules similar to modern rugby.[216] Today Princeton is a member of the Football Championship Subdivision of NCAA Division I.[217] As of the end of the 2010 season, Princeton had won 26 national football championships, more than any other school.[218]

.jpg)

The men's basketball program is noted for its success under Pete Carril, the head coach from 1967 to 1996. During this time, Princeton won 13 Ivy League titles and made 11 NCAA tournament appearances.[219] Carril introduced the Princeton offense, an offensive strategy that has since been adopted by a number of college and professional basketball teams.[220] Carril's final victory at Princeton came when the Tigers beat UCLA, the defending national champion, in the opening round of the 1996 NCAA tournament,[220] in what is considered one of the greatest upsets in the history of the tournament.[221] Recently Princeton tied the record for the fewest points in a Division I game since the institution of the three-point line in 1986–87, when the Tigers scored 21 points in a loss against Monmouth University on Dec 14, 2005.[222]

Princeton women's soccer team advanced to the NCAA Division I Women's Soccer Championship semi-finals in 2004, the only Ivy League team to do so in a 64-team tournament.[223] The season was led by former U.S. National Team member, Esmeralda Negron, Olympic medalist Canadian National Team member Diana Matheson, and coach Julie Shackford.[224] The Tigers men's soccer team was coached for many years by Princeton alumnus and future United States men's national team manager Bob Bradley.

The men's water polo team is currently a dominant force in the Collegiate Water Polo Association, having reached the Final Four in two of the last three years. Similarly, the men's lacrosse program enjoyed a period of dominance 1992–2001, during which time it won six national championships.[225]

Club and intramural

In addition to varsity sports, Princeton hosts about 35 club sports teams.[214] Princeton's rugby team is organized as a club sport.[226]

Each year, nearly 300 teams participate in intramural sports at Princeton.[227] Intramurals are open to members of Princeton's faculty, staff, and students, though a team representing a residential college or eating club must consist only of members of that college or club. Several leagues with differing levels of competitiveness are available.[228]

Songs

Notable among a number of songs commonly played and sung at various events such as commencement, convocation, and athletic games is Princeton Cannon Song, the Princeton University fight song.

Bob Dylan wrote "Day of The Locusts" (for his 1970 album New Morning) about his experience of receiving an honorary doctorate from the University. It is a reference to the negative experience he had and it mentions the Brood X cicada infestation Princeton experienced that June 1970.

"Old Nassau"

"Old Nassau" has been Princeton University's anthem since 1859. Its words were written that year by a freshman, Harlan Page Peck, and published in the March issue of the Nassau Literary Review (the oldest student publication at Princeton and also the second oldest undergraduate literary magazine in the country). The words and music appeared together for the first time in Songs of Old Nassau, published in April 1859. Before the Langlotz tune was written, the song was sung to Auld Lang Syne's melody, which also fits.[229]

However, Old Nassau does not only refer to the university's anthem. It can also refer to Nassau Hall, the building that was built in 1756 and named after William III of the House of Orange-Nassau. When built, it was the largest college building in North America. It served briefly as the capitol of the United States when the Continental Congress convened there in the summer of 1783. By metonymy, the term can refer to the university as a whole. Finally, it can also refer to a chemical reaction that is dubbed "Old Nassau reaction" because the solution turns orange and then black.[230]

Notable people

Alumni

U.S. Presidents James Madison and Woodrow Wilson and Vice President Aaron Burr graduated from Princeton, as did Michelle Obama, the former First Lady of the United States. Former Chief Justice of the United States Oliver Ellsworth was an alumnus, as are current U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justices Samuel Alito, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor. Alumnus Jerome Powell was appointed as Chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve Board in 2018.

Princeton graduates played a major role in the American Revolution, including the first and last Colonels on the Patriot side Philip Johnston and Nathaniel Scudder, as well as the highest ranking civilian leader on the British side David Mathews.

Notable graduates of Princeton's School of Engineering and Applied Science include Apollo astronaut and commander of Apollo 12 Pete Conrad, Amazon CEO and founder Jeff Bezos, former Chairman of Alphabet Inc. Eric Schmidt, and Lisa P. Jackson, former Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency.

Actors Jimmy Stewart, Wentworth Miller, José Ferrer, David Duchovny, Brooke Shields, and Graham Phillips graduated from Princeton as did composer and pianist Richard Aaker Trythall. Soccer-player alumna, Diana Matheson, scored the game-winning goal that earned Canada their Olympic bronze medal in 2012.

Writers Booth Tarkington, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Eugene O'Neill attended but did not graduate. Selden Edwards and Will Stanton graduated with English degrees. American novelist Jodi Picoult graduated in 1987. Mario Vargas Llosa, Nobel Prize in Literature, received an honorary degree in 2015 and has been a visiting lecturer at the Spanish Department.

William P. Ross, Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation and founding editor of the Cherokee Advocate, graduated in 1844.

Notable graduate alumni include Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, Richard Feynman, Lee Iacocca, John Nash, Alonzo Church, Alan Turing, Terence Tao, Edward Witten, John Milnor, John Bardeen, Steven Weinberg, John Tate, and David Petraeus. Royals such as Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad, Prince Moulay Hicham of Morocco, Prince Turki bin Faisal Al Saud, and Queen Noor of Jordan also have attended Princeton.

Faculty

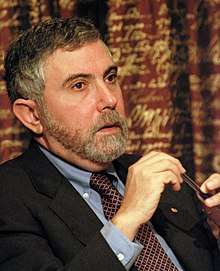

Notable faculty members include P. Adams Sitney, Angus Deaton, Daniel Kahneman, Joyce Carol Oates, Cornel West, Robert Keohane, Anthony Grafton, Peter Singer, Jhumpa Lahiri, Michael Mullen, Robert P. George, and Andrew Wiles. Notable former faculty members include John Witherspoon, Walter Kaufmann, John von Neumann, Ben Bernanke, Paul Krugman, Joseph Henry, Toni Morrison, John P. Lewis, and alumnus Woodrow Wilson, who also served as president of the University 1902–1910.

Albert Einstein, though on the faculty at the Institute for Advanced Study rather than at Princeton, came to be associated with the university through frequent lectures and visits on the campus.

Paul Krugman

Paul Krugman

Nobel Prize in Economics laureate, 2008.jpg)

.jpg)

Daniel C. Tsui, Nobel Prize in Physics laureate, 1998

Daniel C. Tsui, Nobel Prize in Physics laureate, 1998 Edward Felten, Deputy U.S. Chief Technology Officer

Edward Felten, Deputy U.S. Chief Technology Officer

See also

Notes

- Princeton is the fourth institution of higher learning to obtain a collegiate charter, conduct classes, or grant degrees, based upon dates that do not seem to be in dispute. Princeton and the University of Pennsylvania both claim the fourth oldest founding date and the University of Pennsylvania once claimed 1749 as its founding date, making it fifth oldest, but in 1899 its trustees adopted a resolution which asserted 1740 as the founding date.[9][10] To further complicate the comparison of founding dates, a Log College was operated by William and Gilbert Tennent, the Presbyterian ministers, in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, from 1726 until 1746 and it was once common to assert a formal connection between it and the College of New Jersey, which would justify Princeton pushing its founding date back to 1726. However, Princeton has never done so and a Princeton historian says that the facts "do not warrant" such an interpretation.[11] Columbia University was chartered and began collegiate classes in 1754. Columbia considers itself to be the fifth institution of higher learning in the United States, based upon its charter date of 1754 and Penn's charter date of 1755.[12]

- Princeton Theological Seminary and Westminster Choir College maintain cross-registration programs with the university.

References

- Princeton Profile (PDF) (2015-16 ed.). Princeton. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 24, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- "Member Directory". NAICU. P (list by institution). Archived from the original on November 9, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- As of June 30, 2019. "U.S. and Canadian 2019 NTSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2019 Endowment Market Value, and Percentage Change in Market Value from FY18 to FY19 (Revised)". National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "Facts & Figures". Princeton University. Retrieved December 25, 2019.

- "Common Data Set 2018-2019" (PDF). Princeton University. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- "Princeton University". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- Guide to Princeton University's Graphic Identity (PDF). Princeton University Trademark Licensing. December 15, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- "Princeton in the American Revolution". Princeton University, Office of Communications. Retrieved May 7, 2007.

the fourth college to be established in British North America.

- "Building Penn's Brand", Gazette, University of Pennsylvania

- "Princeton vs. Penn: Which is the Older Institution?" (FAQ). Princeton. February 5, 2003. Archived from the original on March 19, 2003.

- "Log College". Princeton. 1978. Archived from the original on November 17, 2005.

- History, Columbia

- ""Princeton's History" — Parent's Handbook, 2005–06". Princeton University. August 2005. Archived from the original on September 4, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2006.

- "About Princeton". Princeton University, Office of Communications. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- "College Endowment Rankings". Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- "Statistics".

- "Princeton University 250th Anniversary Celebration Collection". Library Finding Aids. Princeton University. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- Princeton Alumni Weekly. 1933. p. 487.

- Morrison, Jeffry H (2005), John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic

- University, Princeton. "Ashbel Green – The Presidents of Princeton University". Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- "Princeton Theological Seminary". Archived from the original on May 19, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- "FAQ Princeton Theological Seminary". Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library. Princeton. April 24, 2012. Archived from the original on May 19, 2015. Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- "Partnerships, Exchanges, and Cross-Registration". Princeton University Graduate School. Princeton. April 15, 2014. Archived from the original on June 7, 2014.

- Oberdorfer, Don (1995). Princeton University: The First 250 Years (First ed.). Trustees of Princeton University. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-691-01122-6.

- "U.S. Senate: The Nine Capitals of the United States".

- Leitch, Alexander (1979). "A Princeton Companion: Nassau Hall". Princeton University Press. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- Leitch, Alexander (1978). McCosh, James. A Princeton Companion. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691046549. OCLC 4193433. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- Armstrong, April (July 8, 2015). "When Did the College of New Jersey Change to Princeton University?". Mudd Manuscript Library Blog. Princeton University. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- Oberdorfer, Don (1995). "A Princeton Chronology". Princeton University: The First 250 Years (First ed.). Trustees of Princeton University. pp. 268–269. ISBN 978-0-691-01122-6.

- Griffin, Nathaniel (April 1910). "The Princeton Preceptorial System". The Sewanee Review. 18 (2): 169–176. JSTOR 27532370.

- "Historical Photograph Collection, Lake Carnegie Construction Photographs, circa 1905–1907". Finding Aids. Princeton. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- "Princeton Eating Club Loses Bid to Continue Ban on Women", The Los Angeles Times, Associated Press, p. A4, January 23, 1991

- "Princeton song goes coed", The New York Times, March 1, 1987

- "Princeton University - Presidential committee makes recommendations to strengthen student leadership". Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- "Trustees name garden for Betsey Stockton, arch for Jimmy Johnson". Princeton University. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- Slavery, Princeton & (February 22, 2019). "Princeton & Slavery". Princeton & Slavery. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- Schuessler, Jennifer (November 6, 2017). "Princeton Digs Deep Into Its Fraught Racial History". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- Carp, Alex (February 7, 2018). "Slavery and the American University". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- Slavery, Princeton & (February 22, 2019). "Princeton & Slavery". Princeton & Slavery. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- Sandweiss, Martha A.; Hollander, Craig. "Princeton and Slavery: Holding the Center". Princeton & Slavery Project. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- Schuessler, Jennifer (November 6, 2017). "Putting the Ghosts of Princeton's Racial Past Onstage". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- Urist, Jacoba (November 9, 2017). "A Contemporary Artist Is Helping Princeton Confront Its Ugly Past". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- Schuessler, Jennifer (April 17, 2018). "Princeton to Name Two Campus Spaces in Honor of Slaves". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- "Trustees name garden for Betsey Stockton, arch for Jimmy Johnson". Princeton University. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- "Princeton Seminary and Slavery". Princeton Seminary and Slavery. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- "Report on Slavery and Racism in the History of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary". SBTS. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- "America's most beautiful college campuses". Travel+Leisure. Travelandleisure.com. September 2011. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- "Princeton University: An Interactive Campus History. Chapter II: The College Expands: 1802–1846". Princeton University. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "Princeton University: An Interactive Campus History. Chapter III: Princeton at Mid-Century, 1846–1868". Princeton University. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "Princeton University: An Interactive Campus History. Chapter IV: The McCosh Presidency, 1868–1888". Princeton University. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "Princeton University: An Interactive Campus History. Chapter V: The Rise of the Collegiate Gothic". Princeton University. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "Princeton University: An Interactive Campus History. Chapter VI: Spires and Gargoyles, The Princeton Campus 1900–1917". Princeton University. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "Princeton University: An Interactive Campus History. Chapter VII: Princeton Between the Wars, 1919–1939". Princeton University. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "Princeton University: An Interactive Campus History. Chapter VIII: Princeton at Mid-Century: Campus Architecture, 1933–1960". Princeton University. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "Princeton University: An Interactive Campus History. Chapter IX: The Sixties". Princeton University. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- Lack, Kelly (September 11, 2008). "Lewis Library makes a grand debut". The Daily Princetonian. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- Leitch, Alexander (1978). "A Princeton Companion: Spelman Halls". Princeton University Press. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "Old is new at Princeton". World Architecture News. December 19, 2007. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "Frist Campus Center Iconography". Princeton University. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- Pearson, Clifford A. (November 2003). "Carl Icahn Laboratory". Architectural Record. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- Leitch, Alexander. "A Princeton Companion: Putnam Collection of Sculpture". Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- Peterson, Megan. "Princeton sculpture enriches beauty and character of campus". Princeton University website. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- Leitch, Alexander (1978). "A Princeton Companion: Carnegie Lake". Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "The Richest Man in the World: Andrew Carnegie. Philanthropy 101: Scourge of the Campus". PBS American Experience. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "Princeton University Rowing: Recruiting Information". Princeton University. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- Hageman, John Frelinghuysen (1879). History of Princeton and Its Institutions. 1 (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. p. 139.

- Hageman, John Frelinghuysen (1879). History of Princeton and Its Institutions. 2 (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. pp. 317–8.

- Hageman, John Frelinghuysen (1879). History of Princeton and Its Institutions. 2 (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. pp. 318–9.

- Carroll, Kate (October 5, 2006). "Vandals spraypaint campus Rutgers red". The Daily Princetonian. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- "Official Athletic Site". scarletknights.com. CBS Interactive. The Cannon War. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- "Dear Mr. Mudd: Whose Cannon Is It?". Mudd Manuscript Library Blog. November 11, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- "Bonfire - Office of the Dean of Undergraduate Students - Bonfire". Princeton.edu. November 26, 2013. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- Emily Aronson (February 5, 2019). "University to name courtyard for influential landscape architect Beatrix Farrand". Princeton University. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- "PRINCETON UNIVERSITY MASTER PLAN Princeton, NJ (2005–2008)". Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- Mark F. Bernstein (June 11, 2008). "Growing Campus". Princeton Alumni Weekly. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- Bradner, Ryan (July 14, 2003). "Nassau Hall: National history, center of campus". The Daily Princetonian. In the beginning. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- "Buildings of the Department of State: Nassau Hall, Princeton, NJ". US State Department. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- "A Brief History of the Architecture of Nassau Hall". Mudd Manuscript Library Blog. June 17, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- Wilentz, Sean (May 16, 2001). "Nassau Hall, Princeton, New Jersey". Princeton Alumni Weekly. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- "Commencement Information – Overview". Office of the Vice President & Secretary, Princeton University. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- "New Jersey – Mercer County". National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- "About". Whitman College. Princeton University Office of the Dean of the College. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "Rockefeller College". hres.princeton.edu. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "Mathey College". hres.princeton.edu. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "Butler College". hres.princeton.edu. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- Leitch, Alexander (1978). "West, Andrew Fleming". A Princeton Companion. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691046549. OCLC 4193433.

- "Forbes College". hres.princeton.edu. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "About | Whitman College". whitmancollege.princeton.edu. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- Sacks, Benjamin (June 2011). "Harvard's "Constructed Utopia" and the Culture of Deception: The Expansion toward the Charles River, 1902-1932". The New England Quarterly. 84 (2): 286–317. doi:10.1162/TNEQ_a_00090.

- "New Graduate College". hres.princeton.edu. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "The American Theatre Wing's Tony Awards – Official Website by IBM". Tony awards. May 1, 2000. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- "The Houses of Parliament, Seagulls (y1979-54)". artmuseum.princeton.edu. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Meadow at Giverny (y1954-78)". artmuseum.princeton.edu. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge (y1972-15)". artmuseum.princeton.edu. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Search the Collection | Princeton University Art Museum". artmuseum.princeton.edu. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Tarascon Stagecoach (L.1988.62.11)". artmuseum.princeton.edu. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Blue Marilyn (y1978-46)". artmuseum.princeton.edu. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- Bush, Sara. "The University Chapel". Princeton University. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- Milliner, Matthew J. (Spring 2009). "Primus inter pares: Albert M. Friend and the argument of the Princeton University Chapel". The Princeton University Library Chronicle. 70 (3). pp. 470–517.

- "Religion: Princeton's chapel". Time. June 11, 1928. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- Greenwood, Kathryn Federici (March 13, 2002). "Features: Chapel gets facelift and a new dean". Princeton Alumni Weekly. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- Stillwell, Richard (1971). The Chapel of Princeton University. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stinnard, Michelle (February 10, 2006). "Restoration secures chapel at Ivy League campus". Stone World. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Stillwell 1971, pp. 7–9.

- "Open Facilities – A Princeton Profile". Princeton University. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- "Chapel Architecture and Features". Orange Key Virtual Tour. Princeton. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- "University Chapel". Princeton University Office of Religious Life. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- The Aquinas Institute. "Schedule and Events". The Aquinas Institute: Princeton University's Catholic Chaplaincy (blog). Blogger. Holy Mass Schedule. Archived from the original on August 30, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Prayer". Princeton University's Catholic Campus Ministry. The Aquinas Institute. Sacraments. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- "Murray-Dodge Hall". Religious LIfe. Princeton. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

Beginning August 24, 2015, the Office of Religious Life is moving temporarily to Green Hall...while Murray-Dodge Hall is renovated.

- "Office of Religious Life Café". Religious Life. Princeton University. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- "Places of Peace". Religious Life. Princeton University. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- "Deans of Religious Life". Religious LIfe. Princeton. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- "Hindu and Muslim life coordinators named". Princeton University News. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- Apartment housing, Princeton University, archived from the original on May 1, 2012, retrieved February 10, 2012

- "Princeton University adopts its Sustainability Plan in February 2008". Sustainability at Princeton. Princeton University. Archived from the original on November 15, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- "All Goals and Key Progress". Sustainability at Princeton. Princeton University. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- "Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reductions". Princeton University. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- "Report on Sustainability 2009". Princeton University Reports. Princeton University. October 27, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- "Green Purchasing at Princeton". Princeton University. Archived from the original on December 24, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- Osellame, Julia (March 29, 2007). "Green is the new orange: Princeton conserves". The Daily Princetonian. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- As of June 30, 2019. "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY 2018 to FY 2019". National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "Colleges with the Biggest Endowment Per Student". CNBC.com. Praefcke, Andreas (photo credit). 2011. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Epstein, Jennifer (October 27, 2006). "Endowment Climbs Past $13 Billion". The Daily Princetonian. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- "Departments & Programs". Princeton University. October 1, 2015. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- "About Us". Honor Committee. Princeton University. May 19, 2015. Role of Honor Committee. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- "Honor Code". The Student Guide to Princeton. Princeton University. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- Honor Code (YouTube video). music and lyrics by Peter Mills. 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2015.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Committee on Discipline". ODUS: Office of the Dean of Undergraduate Students. Princeton University. August 25, 2015. Archived from the original on November 3, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- "Acknowledging Your Sources". Academic Integrity. Princeton University. August 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- "Common Data Set 2017-2018" (PDF). Princeton University. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Common Data Set 2016-2017" (PDF). Princeton University. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 20, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 10, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 20, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Staff (September 18, 2006). "Princeton to end early admission". Princeton University. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- Staff (February 24, 2011). "Princeton to reinstate early admission program". Princeton University. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- Thomas, G. Scott (December 12, 2011). "Princeton is the most selective college in the Eastern US". The Business Journal. Retrieved October 25, 2015.