Claude Monet

Oscar-Claude Monet (UK: /ˈmɒneɪ/, US: /moʊˈneɪ/,[1][2] French: [klod mɔnɛ]; 14 November 1840 – 5 December 1926) was a French painter, a founder of French Impressionist painting and the most consistent and prolific practitioner of the movement's philosophy of expressing one's perceptions before nature, especially as applied to plein air landscape painting.[3][4] The term "Impressionism" is derived from the title of his painting Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise), which was exhibited in 1874 in the first of the independent exhibitions mounted by Monet and his associates as an alternative to the Salon de Paris.[5]

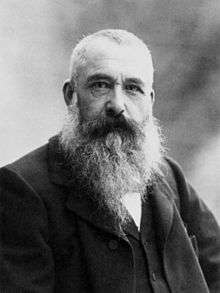

Claude Monet | |

|---|---|

Claude Monet, photo by Nadar, 1899 | |

| Born | Oscar-Claude Monet 14 November 1840 Paris, France |

| Died | 5 December 1926 (aged 86) Giverny, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painter |

Notable work | Impression, Sunrise Rouen Cathedral series London Parliament series Water Lilies Haystacks Poplars |

| Movement | Impressionism |

| Patron(s) | Gustave Caillebotte, Ernest Hoschedé, Georges Clemenceau |

Monet's ambition of documenting the French countryside led him to adopt a method of painting the same scene many times in order to capture the changing of light and the passing of the seasons.[6] From 1883, Monet lived in Giverny, where he purchased a house and property and began a vast landscaping project which included lily ponds that would become the subjects of his best-known works. He began painting the water lilies in 1899, first in vertical views with a Japanese bridge as a central feature and later in the series of large-scale paintings that was to occupy him continuously for the next 20 years of his life.

Biography

Birth and childhood

Claude Monet was born on 14 November 1840 on the fifth floor of 45 rue Laffitte, in the 9th arrondissement of Paris.[7] He was the second son of Claude Adolphe Monet and Louise Justine Aubrée Monet, both of them second-generation Parisians. On 20 May 1841, he was baptized in the local parish church, Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, as Oscar-Claude, but his parents called him simply Oscar.[7][8] (He signed his juvenilia "O. Monet".) Despite being baptized Catholic, Monet later became an atheist.[9][10]

In 1845, his family moved to Le Havre in Normandy. His father wanted him to go into the family's ship-chandling and grocery business,[11] but Monet wanted to become an artist. His mother was a singer, and supported Monet's desire for a career in art.[12]

On 1 April 1851, Monet entered Le Havre secondary school of the arts. Locals knew him well for his charcoal caricatures, which he would sell for ten to twenty francs. Monet also undertook his first drawing lessons from Jacques-François Ochard, a former student of Jacques-Louis David. On the beaches of Normandy around 1856 he met fellow artist Eugène Boudin, who became his mentor and taught him to use oil paints. Boudin taught Monet "en plein air" (outdoor) techniques for painting.[13] Both were influenced by Johan Barthold Jongkind.

On 28 January 1857, his mother died. At the age of sixteen, he left school and went to live with his widowed, childless aunt, Marie-Jeanne Lecadre.

Paris and Algeria

When Monet traveled to Paris to visit the Louvre, he witnessed painters copying from the old masters. Having brought his paints and other tools with him, he would instead go and sit by a window and paint what he saw.[14] Monet was in Paris for several years and met other young painters, including Édouard Manet and others who would become friends and fellow Impressionists.

After drawing a low ballot number in March 1861, Monet was drafted into the First Regiment of African Light Cavalry (Chasseurs d'Afrique) in Algeria for a seven-year period of military service. His prosperous father could have purchased Monet's exemption from conscription but declined to do so when his son refused to give up painting. While in Algeria, Monet did only a few sketches of casbah scenes, a single landscape, and several portraits of officers, all of which have been lost. In a Le Temps interview of 1900 however he commented that the light and vivid colours of North Africa "contained the germ of my future researches".[15] After about a year of garrison duty in Algiers, Monet contracted typhoid fever and briefly went absent without leave. Following convalescence, Monet's aunt intervened to remove him from the army if he agreed to complete a course at an art school. It is possible that the Dutch painter Johan Barthold Jongkind, whom Monet knew, may have prompted his aunt on this matter.

Disillusioned with the traditional art taught at art schools, in 1862 Monet became a student of Charles Gleyre in Paris, where he met Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille and Alfred Sisley. Together they shared new approaches to art, painting the effects of light en plein air with broken colour and rapid brushstrokes, in what later came to be known as Impressionism.

In January 1865 Monet was working on a version of Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, aiming to present it for hanging at the Salon, which had rejected Manet's Le déjeuner sur l'herbe two years earlier.[17] Monet's painting was very large and could not be completed in time. (It was later cut up, with parts now in different galleries.) Monet submitted instead a painting of Camille or The Woman in the Green Dress (La femme à la robe verte), one of many works using his future wife, Camille Doncieux, as his model. Both this painting and a small landscape were hung.[17] The following year Monet used Camille for his model in Women in the Garden, and On the Bank of the Seine, Bennecourt in 1868. Camille became pregnant and gave birth to their first child, Jean, in 1867.[18] Monet and Camille married on 28 June 1870, just before the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War,[19] and, after their excursion to London and Zaandam, they moved to Argenteuil, in December 1871. During this time Monet painted various works of modern life. He and Camille lived in poverty for most of this period. Following the successful exhibition of some maritime paintings, and the winning of a silver medal at Le Havre, Monet's paintings were seized by creditors, from whom they were bought back by a shipping merchant, Gaudibert, who was also a patron of Boudin.[17]

Impressionism

From the late 1860s, Monet and other like-minded artists met with rejection from the conservative Académie des Beaux-Arts, which held its annual exhibition at the Salon de Paris. During the latter part of 1873, Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley organized the Société anonyme des artistes peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs (Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers) to exhibit their artworks independently. At their first exhibition, held in April 1874, Monet exhibited the work that was to give the group its lasting name. He was inspired by the style and subject matter of previous modern painters Camille Pissarro and Edouard Manet.[20]

Impression, Sunrise was painted in 1872, depicting a Le Havre port landscape. From the painting's title the art critic Louis Leroy, in his review, "L'Exposition des Impressionnistes," which appeared in Le Charivari, coined the term "Impressionism".[21] It was intended as disparagement but the Impressionists appropriated the term for themselves.[22][23]

Franco-Prussian War and Argenteuil

After the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War (19 July 1870), Monet and his family took refuge in England in September 1870,[24] where he studied the works of John Constable and Joseph Mallord William Turner, both of whose landscapes would serve to inspire Monet's innovations in the study of colour. In the spring of 1871, Monet's works were refused authorisation for inclusion in the Royal Academy exhibition.[19]

In May 1871, he left London to live in Zaandam, in the Netherlands,[19] where he made twenty-five paintings (and the police suspected him of revolutionary activities).[25] He also paid a first visit to nearby Amsterdam. In October or November 1871, he returned to France. From December 1871 to 1878 he lived at Argenteuil, a village on the right bank of the Seine river near Paris, and a popular Sunday-outing destination for Parisians, where he painted some of his best-known works. In 1873, Monet purchased a small boat equipped to be used as a floating studio.[26] From the boat studio Monet painted landscapes and also portraits of Édouard Manet and his wife; Manet in turn depicted Monet painting aboard the boat, accompanied by Camille, in 1874.[26] In 1874, he briefly returned to Holland.[27]

Impressionism

The first Impressionist exhibition was held in 1874 at 35 boulevard des Capucines, Paris, from 15 April to 15 May. The primary purpose of the participants was not so much to promote a new style, but to free themselves from the constraints of the Salon de Paris. The exhibition, open to anyone prepared to pay 60 francs, gave artists the opportunity to show their work without the interference of a jury.[28][29][30]

Renoir chaired the hanging committee and did most of the work himself, as others members failed to present themselves.[28][29]

In addition to Impression: Sunrise (pictured above), Monet presented four oil paintings and seven pastels. Among the paintings he displayed was The Luncheon (1868), which features Camille Doncieux and Jean Monet, and which had been rejected by the Paris Salon of 1870.[31] Also in this exhibition was a painting titled Boulevard des Capucines, a painting of the boulevard done from the photographer Nadar's apartment at no. 35. Monet painted the subject twice, and it is uncertain which of the two pictures, that now in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, or that in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, was the painting that appeared in the groundbreaking 1874 exhibition, though more recently the Moscow picture has been favoured.[32][33] Altogether, 165 works were exhibited in the exhibition, including 4 oils, 2 pastels and 3 watercolours by Morisot; 6 oils and 1 pastel by Renoir; 10 works by Degas; 5 by Pissarro; 3 by Cézanne; and 3 by Guillaumin. Several works were on loan, including Cézanne's Modern Olympia, Morisot's Hide and Seek (owned by Manet) and 2 landscapes by Sisley that had been purchased by Durand-Ruel.[28][29][30]

The total attendance is estimated at 3500, and some works did sell, though some exhibitors had placed their prices too high. Pissarro was asking 1000 francs for The Orchard and Monet the same for Impression: Sunrise, neither of which sold. Renoir failed to obtain the 500 francs he was asking for La Loge, but later sold it for 450 francs to Père Martin, dealer and supporter of the group.[28][29][30]

- Paintings 1858–1872

.jpg)

Mouth of the Seine at Honfleur, 1865, Norton Simon Foundation, Pasadena, CA; indicates the influence of Dutch maritime painting.[34]

Mouth of the Seine at Honfleur, 1865, Norton Simon Foundation, Pasadena, CA; indicates the influence of Dutch maritime painting.[34]

Woman in the Garden, 1867, Hermitage, St. Petersburg; a study in the effect of sunlight and shadow on colour

Woman in the Garden, 1867, Hermitage, St. Petersburg; a study in the effect of sunlight and shadow on colour Garden at Sainte-Adresse ("Jardin à Sainte-Adresse"), 1867, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[36]

Garden at Sainte-Adresse ("Jardin à Sainte-Adresse"), 1867, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[36]

La Grenouillére 1869, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; a small plein-air painting created with broad strokes of intense colour.[38]

La Grenouillére 1869, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; a small plein-air painting created with broad strokes of intense colour.[38] The Magpie, 1868–1869. Musée d'Orsay, Paris; one of Monet's early attempts at capturing the effect of snow on the landscape. See also Snow at Argenteuil.

The Magpie, 1868–1869. Musée d'Orsay, Paris; one of Monet's early attempts at capturing the effect of snow on the landscape. See also Snow at Argenteuil.%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_54_x_65.7_cm%2C_Museum_of_Fine_Arts%2C_Budapest.jpg) Le port de Trouville (Breakwater at Trouville, Low Tide), 1870, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.[39]

Le port de Trouville (Breakwater at Trouville, Low Tide), 1870, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.[39] La plage de Trouville, 1870, National Gallery, London. The left figure may be Camille, on the right possibly the wife of Eugène Boudin, whose beach scenes influenced Monet.[40]

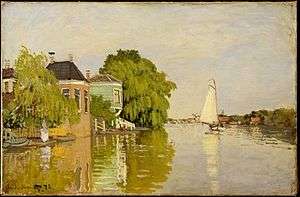

La plage de Trouville, 1870, National Gallery, London. The left figure may be Camille, on the right possibly the wife of Eugène Boudin, whose beach scenes influenced Monet.[40] Houses on the Achterzaan, 1871, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Houses on the Achterzaan, 1871, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Jean Monet on his hobby horse, 1872, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Jean Monet on his hobby horse, 1872, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Springtime 1872, Walters Art Museum

Springtime 1872, Walters Art Museum

Death of Camille

In 1876, Camille Monet became ill with tuberculosis. Their second son, Michel, was born on 17 March 1878. This second child weakened her already fading health. In the summer of that year, the family moved to the village of Vétheuil where they shared a house with the family of Ernest Hoschedé, a wealthy department store owner and patron of the arts. In 1878, Camille Monet was diagnosed with uterine cancer.[41][42][43] She died on 5 September 1879 at the age of thirty-two.[44][45]

Monet made a study in oils of his dead wife. Many years later, Monet confessed to his friend Georges Clemenceau that his need to analyse colours was both the joy and torment of his life. He explained,

I one day found myself looking at my beloved wife's dead face and just systematically noting the colours according to an automatic reflex!

John Berger describes the work as "a blizzard of white, grey, purplish paint ... a terrible blizzard of loss which will forever efface her features. In fact there can be very few death-bed paintings which have been so intensely felt or subjectively expressive."[46]

Vétheuil

After several difficult months following the death of Camille, Monet began to create some of his best paintings of the 19th century. During the early 1880s, Monet painted several groups of landscapes and seascapes in what he considered to be campaigns to document the French countryside. These began to evolve into series of pictures in which he documented the same scene many times in order to capture the changing of light and the passing of the seasons.

Monet's friend Ernest Hoschedé became bankrupt, and left in 1878 for Belgium. After the death of Camille Monet in September 1879, and while Monet continued to live in the house in Vétheuil, Alice Hoschedé helped Monet to raise his two sons, Jean and Michel. She took them to Paris to live alongside her own six children,[47] Blanche (who married Jean Monet), Germaine, Suzanne, Marthe, Jean-Pierre, and Jacques. In the spring of 1880, Alice Hoschedé and all the children left Paris and rejoined Monet at Vétheuil.[48] In 1881, all of them moved to Poissy, which Monet hated. In April 1883, looking out the window of the little train between Vernon and Gasny, he discovered Giverny in Normandy.[47][49][50] Monet, Alice Hoschedé and the children moved to Vernon, then to the house in Giverny, where he planted a large garden and where he painted for much of the rest of his life. Following the death of her estranged husband, Monet married Alice Hoschedé in 1892.[13]

- Paintings 1873–1879

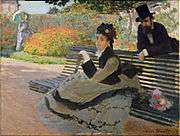

Camille Monet on a Garden Bench, 1873, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Camille Monet on a Garden Bench, 1873, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The Artist's house at Argenteuil, 1873, The Art Institute of Chicago

The Artist's house at Argenteuil, 1873, The Art Institute of Chicago Coquelicots, La promenade (Poppies), 1873, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Coquelicots, La promenade (Poppies), 1873, Musée d'Orsay, Paris Argenteuil, 1874, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Argenteuil, 1874, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. The Studio Boat, 1874, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

The Studio Boat, 1874, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

Flowers on the riverbank at Argenteuil, 1877, Pola Museum of Art, Japan

Flowers on the riverbank at Argenteuil, 1877, Pola Museum of Art, Japan Arrival of the Normandy Train, Gare Saint-Lazare, 1877, The Art Institute of Chicago

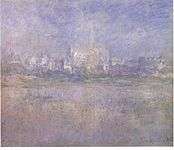

Arrival of the Normandy Train, Gare Saint-Lazare, 1877, The Art Institute of Chicago Vétheuil in the Fog, 1879, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Vétheuil in the Fog, 1879, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Giverny

Monet's house and garden

Monet rented and eventually purchased a house and gardens in Giverny. At the beginning of May 1883, Monet and his large family rented the home and 8,000 square metres (2.0 acres) from a local landowner. The house was situated near the main road between the towns of Vernon and Gasny at Giverny. There was a barn that doubled as a painting studio, orchards and a small garden. The house was close enough to the local schools for the children to attend, and the surrounding landscape offered many suitable motifs for Monet's work.

The family worked and built up the gardens, and Monet's fortunes began to change for the better as his dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, had increasing success in selling his paintings.[51] By November 1890, Monet was prosperous enough to buy the house, the surrounding buildings and the land for his gardens. During the 1890s, Monet built a greenhouse and a second studio, a spacious building well lit with skylights.

Monet wrote daily instructions to his gardener, precise designs and layouts for plantings, and invoices for his floral purchases and his collection of botany books. As Monet's wealth grew, his garden evolved. He remained its architect, even after he hired seven gardeners.[52]

Monet purchased additional land with a water meadow. In 1893 he began a vast landscaping project which included lily ponds that would become the subjects of his best-known works. White water lilies local to France were planted along with imported cultivars from South America and Egypt, resulting in a range of colours including yellow, blue and white lilies that turned pink with age.[53] In 1899 he began painting the water lilies, first in vertical views with a Japanese bridge as a central feature, and later in the series of large-scale paintings that was to occupy him continuously for the next 20 years of his life.[54] This scenery, with its alternating light and mirror-like reflections, became an integral part of his work. By the mid-1910s Monet had achieved:

"a completely new, fluid, and somewhat audacious style of painting in which the water-lily pond became the point of departure for an almost abstract art".

- Monet's garden

In the Garden, 1895, Collection E. G. Buehrle, Zürich

In the Garden, 1895, Collection E. G. Buehrle, Zürich- Agapanthus, between 1914 and 1926, Museum of Modern Art, New York

- Flowering Arches, Giverny, 1913, Phoenix Art Museum

-Monet.jpg) Water Lilies and the Japanese bridge, 1897–1899, Princeton University Art Museum

Water Lilies and the Japanese bridge, 1897–1899, Princeton University Art Museum Water Lilies, 1906, Art Institute of Chicago

Water Lilies, 1906, Art Institute of Chicago Water Lilies, Musée Marmottan Monet

Water Lilies, Musée Marmottan Monet Water Lilies, c. 1915, Neue Pinakothek, Munich

Water Lilies, c. 1915, Neue Pinakothek, Munich Water Lilies, c. 1915, Musée Marmottan Monet

Water Lilies, c. 1915, Musée Marmottan Monet

Last years

Failing sight

Monet's second wife, Alice, died in 1911, and his oldest son Jean, who had married Alice's daughter Blanche, Monet's particular favourite, died in 1914.[13] After Alice died, Blanche looked after and cared for Monet. It was during this time that Monet began to develop the first signs of cataracts.[57]

During World War I, in which his younger son Michel served and his friend and admirer Georges Clemenceau led the French nation, Monet painted a series of weeping willow trees as homage to the French fallen soldiers. In 1923, he underwent two operations to remove his cataracts. The paintings done while the cataracts affected his vision have a general reddish tone, which is characteristic of the vision of cataract victims. It may also be that after surgery he was able to see certain ultraviolet wavelengths of light that are normally excluded by the lens of the eye; this may have had an effect on the colours he perceived. After his operations he even repainted some of these paintings, with bluer water lilies than before.[58]

Death

Monet died of lung cancer on 5 December 1926 at the age of 86 and is buried in the Giverny church cemetery.[49] Monet had insisted that the occasion be simple; thus only about fifty people attended the ceremony.[59] At his funeral, his long-time friend Georges Clemenceau removed the black cloth draped over the coffin, stating, "No black for Monet!" and replaced it with a flower-patterned cloth.[60] Monet did not leave a will and so his son Michel inherited his entire estate.

Monet's home, garden, and waterlily pond were bequeathed by Michel to the French Academy of Fine Arts (part of the Institut de France) in 1966. Through the Fondation Claude Monet, the house and gardens were opened for visits in 1980, following restoration.[61] In addition to souvenirs of Monet and other objects of his life, the house contains his collection of Japanese woodcut prints. The house and garden, along with the Museum of Impressionism, are major attractions in Giverny, which hosts tourists from all over the world.

- Monet's late paintings

Water Lilies and Reflections of a Willow (1916–1919), Musée Marmottan Monet

Water Lilies and Reflections of a Willow (1916–1919), Musée Marmottan Monet- Water-Lily Pond and Weeping Willow, 1916–1919, Sale Christie's New York, 1998

- Weeping Willow, 1918–19, Columbus Museum of Art

Weeping Willow, 1918–19, Kimball Art Museum, Fort Worth, Monet's Weeping Willow paintings were an homage to the fallen French soldiers of World War I

Weeping Willow, 1918–19, Kimball Art Museum, Fort Worth, Monet's Weeping Willow paintings were an homage to the fallen French soldiers of World War I House Among the Roses, between 1917 and 1919, Albertina, Vienna

House Among the Roses, between 1917 and 1919, Albertina, Vienna The Rose Walk, Giverny, 1920–1922, Musée Marmottan Monet

The Rose Walk, Giverny, 1920–1922, Musée Marmottan Monet- The Japanese Footbridge, 1920–1922, Museum of Modern Art

The Garden at Giverny

The Garden at Giverny

Monet's methods

Monet has been described as "the driving force behind Impressionism".[62] Crucial to the art of the Impressionist painters was the understanding of the effects of light on the local colour of objects, and the effects of the juxtaposition of colours with each other.[63] Monet's long career as a painter was spent in the pursuit of this aim.

In 1856, his chance meeting with Eugene Boudin, a painter of small beach scenes, opened his eyes to the possibility of plein-air painting. From that time, with a short interruption for military service, he dedicated himself to searching for new and improved methods of painterly expression. To this end, as a young man, he visited the Paris Salon and familiarised himself with the works of older painters, and made friends with other young artists.[62] The five years that he spent at Argenteuil, spending much time on the River Seine in a little floating studio, were formative in his study of the effects of light and reflections. He began to think in terms of colours and shapes rather than scenes and objects. He used bright colours in dabs and dashes and squiggles of paint. Having rejected the academic teachings of Gleyre's studio, he freed himself from theory, saying "I like to paint as a bird sings."[64]

In 1877 a series of paintings at St-Lazare Station had Monet looking at smoke and steam and the way that they affected colour and visibility, being sometimes opaque and sometimes translucent. He was to further use this study in the painting of the effects of mist and rain on the landscape.[65] The study of the effects of atmosphere was to evolve into a number of series of paintings in which Monet repeatedly painted the same subject (such as his water lilies series)[66] in different lights, at different hours of the day, and through the changes of weather and season. This process began in the 1880s and continued until the end of his life in 1926.

His first series exhibited as such was of Haystacks, painted from different points of view and at different times of the day. Fifteen of the paintings were exhibited at the Galerie Durand-Ruel in 1891. In 1892 he produced what is probably his best-known series, twenty-six views of Rouen Cathedral.[63] In these paintings Monet broke with painterly traditions by cropping the subject so that only a portion of the façade is seen on the canvas. The paintings do not focus on the grand Medieval building, but on the play of light and shade across its surface, transforming the solid masonry.[67]

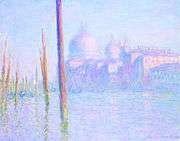

Other series include Poplars, Mornings on the Seine, and the Water Lilies that were painted on his property at Giverny. Between 1883 and 1908, Monet traveled to the Mediterranean, where he painted landmarks, landscapes, and seascapes, including a series of paintings in Venice. In London he painted four series: the Houses of Parliament, London, Charing Cross Bridge, Waterloo Bridge, and Views of Westminster Bridge. Helen Gardner writes:

Monet, with a scientific precision, has given us an unparalleled and unexcelled record of the passing of time as seen in the movement of light over identical forms.[68]

- Series of paintings

La Gare Saint-Lazare, 1877, Musée d'Orsay

La Gare Saint-Lazare, 1877, Musée d'Orsay Arrival of the Normandy Train, Gare Saint-Lazare, 1877, The Art Institute of Chicago[69]

Arrival of the Normandy Train, Gare Saint-Lazare, 1877, The Art Institute of Chicago[69] The Cliffs at Etretat, 1885, Clark Institute, Williamstown

The Cliffs at Etretat, 1885, Clark Institute, Williamstown Sailboats behind the needle at Etretat, 1885

Sailboats behind the needle at Etretat, 1885 Two paintings from a series of grainstacks, 1890–91: Grainstacks in the Sunlight, Morning Effect,

Two paintings from a series of grainstacks, 1890–91: Grainstacks in the Sunlight, Morning Effect, Grainstacks, end of day, Autumn, 1890–1891, Art Institute of Chicago

Grainstacks, end of day, Autumn, 1890–1891, Art Institute of Chicago Poplars (Autumn), 1891, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Poplars (Autumn), 1891, Philadelphia Museum of Art Poplars at the River Epte, 1891 Tate

Poplars at the River Epte, 1891 Tate- The Seine Near Giverny, 1897, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Morning on the Seine, 1898, National Museum of Western Art

Morning on the Seine, 1898, National Museum of Western Art Charing Cross Bridge, 1899, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum Madrid

Charing Cross Bridge, 1899, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum Madrid.jpg) Charing Cross Bridge, London, 1899–1901, Saint Louis Art Museum

Charing Cross Bridge, London, 1899–1901, Saint Louis Art Museum Two paintings from a series of The Houses of Parliament, London, 1900–01, Art Institute of Chicago

Two paintings from a series of The Houses of Parliament, London, 1900–01, Art Institute of Chicago London, Houses of Parliament. The Sun Shining through the Fog, 1904, Musée d'Orsay

London, Houses of Parliament. The Sun Shining through the Fog, 1904, Musée d'Orsay Grand Canal, Venice, 1908, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Grand Canal, Venice, 1908, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Grand Canal, Venice, 1908, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Grand Canal, Venice, 1908, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Fame

In 2004, London, the Parliament, Effects of Sun in the Fog (Londres, le Parlement, trouée de soleil dans le brouillard; 1904), sold for US$20.1 million.[70] In 2006, the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society published a paper providing evidence that these were painted in situ at St Thomas' Hospital over the river Thames.[71]

Falaises près de Dieppe (Cliffs Near Dieppe) has been stolen on two separate occasions: once in 1998 (in which the museum's curator was convicted of the theft and jailed for five years and two months along with two accomplices) and most recently in August 2007.[72] It was recovered in June 2008.[73]

Monet's Le Pont du chemin de fer à Argenteuil, an 1873 painting of a railway bridge spanning the Seine near Paris, was bought by an anonymous telephone bidder for a record $41.4 million at Christie's auction in New York on 6 May 2008. The previous record for his painting stood at $36.5 million.[74] A few weeks later, Le bassin aux nymphéas (from the water lilies series) sold at Christie's 24 June 2008 auction in London[75] for £40,921,250 ($80,451,178), nearly doubling the record for the artist.[76]

This purchase represented one of the top 20 highest prices paid for a painting at the time.

In October 2013, Monet's paintings, L'Eglise de Vetheuil and Le Bassin aux Nympheas, became subjects of a legal case in New York against NY-based Vilma Bautista, one-time aide to Imelda Marcos, wife of dictator Ferdinand Marcos,[77] after she sold Le Bassin aux Nympheas for $32 million to a Swiss buyer. The said Monet paintings, along with two others, were acquired by Imelda during her husband's presidency and allegedly bought using the nation's funds. Bautista's lawyer claimed that the aide sold the painting for Imelda but did not have a chance to give her the money. The Philippine government seeks the return of the painting.[77] Le Bassin aux Nympheas, also known as Japanese Footbridge over the Water-Lily Pond at Giverny, is part of Monet's famed Water Lilies series.

- Series of water lilies in different lights

Le Bassin Aux Nymphéas, 1919. Monet's late series of Waterlily paintings are among his best-known works.

Le Bassin Aux Nymphéas, 1919. Monet's late series of Waterlily paintings are among his best-known works. Water Lilies, 1919, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Water Lilies, 1919, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York- Water Lilies, 1917–1919, Honolulu Museum of Art

Water lilies (Yellow Nirwana), 1920, The National Gallery, London, London

Water lilies (Yellow Nirwana), 1920, The National Gallery, London, London Water Lilies, c. 1915–1926, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Water Lilies, c. 1915–1926, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art The Water Lily Pond, c. 1917–1919, Albertina, Vienna

The Water Lily Pond, c. 1917–1919, Albertina, Vienna

References

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- House, John, et al.: Monet in the 20th century, page 2, Yale University Press, 1998.

- "Claude MONET biography". Giverny.org. 2 December 2009. Archived from the original on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- "Impressionism – Styles & Movements". artinthepicture.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- "Style And Vision Of Claude Monet Impressionist Paintings – Art & Culture". 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- P. Tucker Claude Monet: Life and Art, p. 5

- Patin, Sylvie, Monet : « un œil... mais, bon Dieu, quel œil ! », collection "Découvertes Gallimard" (nº 131), série Arts. p. 14.

- Steven Z. Levine (1994). "6". Monet, Narcissus, and Self-Reflection: The Modernist Myth of the Self (2 ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-226-47543-1.

Much closer to Monet's own atheism and pessimism is Schopenhauer, already introduced to the impressionist circle in the criticism of Theodore Duret in the 1870s and whose influence in France was at its peak in 1886, the year of The World as Will and Idea.

- Ruth Butler (2008). Hidden in the Shadow of the Master: the Model-wives of Cézanne, Monet, and Rodin. Yale University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-300-14953-1.

Then Monet took the end of his brush and drew some long straight strokes in the wet pigment across her chest. It's not clear, and probably not consciously intended by the atheist Claude Monet, but somehow the suggestion of a Cross lies there on her body.

- The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1 January 1974. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-85229-290-7.

- "Claude Monet Biography". biography.com. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- Biography for Claude Monet Archived 20 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine Guggenheim Collection. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- Tinterow, Gary (1994). Origins of Impressionism. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-717-4.

- Jeffrey Meyers, "Monet in Algeria", pp 19–24 "History Today" April 2015

- Musée d'Orsay, Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, Notice de l'œuvre, Iconographie

- Charles F. Stuckey, pp. 11–16

- "Metropolitan Museum of Art". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- Charles Stuckey "Monet, a Retrospective", Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, 195

- Haine, Scott (2000). The History of France (1st ed.). Greenwood Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-313-30328-9.

- From John Rewald, The History of Impressionism

- Distel, Anne; Hoog, Michel; Moffett, Charles S.; N.Y.), Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York (11 April 1974). Impressionism: A Centenary Exhibition, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, December 12, 1974–February 10, 1975. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-097-7 – via Google Books.

- Impressionism – Overview Archived 2 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine ARTinthePICTURE.com. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- Monet, Claude Nicolas Pioch, www.ibiblio.org, 19 September 2002. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- The texts of seven police reports, written on 2 June – 9 October 1871 are included in Monet in Holland, the catalog of an exhibition in the Amsterdam Van Gogh Museum (1986).

- Wattenmaker, Richard J.; Distel, Anne, et al. (1993). Great French Paintings from the Barnes Foundation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 98. ISBN 0-679-40963-7

- His paintings are shown and discussed here "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 May 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- Bernard Denvir, The Chronicle of Impressionism: A Timeline History of Impressionist Art, Bulfinch Press Book, 1993

- Bernard Denvir, The chronicle of impressionism: an intimate diary of the lives and world of the great artists, Thames & Hudson, Limited, 1993

- "The First Impressionist Exhibition, 1874 – Notes". artchive.com.

- "Das Städel Museum – Kunstmuseum in Frankfurt". Städel Museum.

- Nathalia Brodskaya, Claude Monet, Parkstone International, Jul 1, 2011

- Nathalia Brodskaïa, Impressionism, Parkstone International, 2010

- "Search the Collection » Norton Simon Museum". nortonsimon.org.

- "Musée d'Orsay: Claude Monet Women in the Garden". musee-orsay.fr.

- "Claude Monet – Garden at Sainte-Adresse". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum.

- "Das Städel Museum – Kunstmuseum in Frankfurt". Städel Museum.

- "Claude Monet – La Grenouillère". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum.

- "Artwork". szepmuveszeti.hu. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- London, The National Gallery. "Claude Monet - The Beach at Trouville - NG3951 - National Gallery, London". nationalgallery.org.uk.

- Jiminez, Jill Berk (2013). Dictionary of Artists' Models. Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 1-135-95914-5.

- Rose-Marie Hagen; Rainer Hagen (2003). What Great Paintings Say. Taschen. p. 391. ISBN 978-3-8228-1372-0.

- "Monet and Camille, Biography". Intermonet.com. 12 November 2006. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "La Japonaise". artelino. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- "AIM". members.aol.com. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Berger, John (1985). The Eyes of Claude Monet from Sense of Sight. New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0-679-73722-3.

- "Biography of Oscar-Claude Monet, The Life and Work of Claude Monet". Monetalia.com. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- Charles Merrill Mount, Monet a biography, Simon & Schuster publisher, copyright 1966, pp. 309–322.

- "Monet's Village". Giverny. 24 February 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- Charles Merrill Mount, Monet a biography, Simon & Schuster publisher, copyright 1966, p. 326.

- Mary Mathews Gedo, Monet and His Muse: Camille Monet in the Artist's Life, University of Chicago Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-226-28480-4

- Garrett, Robert (20 May 2007). "Monet's gardens a draw to Giverny and to his art". Globe Correspondents. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- Art Gallery of Victoria, Monet's Garden Archived 16 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, (retrieved 16 December 2013)

- "Water Lilies 1919". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Water Lilies, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

- Gary Tinterow, Modern Europe, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), Jan 1, 1987

- Forge, Andrew, and Gordon, Robert, Monet, page 224. Harry N. Abrams, 1989.

- Let the light shine in Guardian News, 30 May 2002. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- P. Tucker Claude Monet: Life and Art, p. 224

- McAuliffe, Mary (2011). Dawn of the Belle Epoque: The Paris of Monet, Zola, Bernhardt, Eiffel, Debussy, Clemenceau, and Their Friends (Paperback). Canberra: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 338. ISBN 978-1-4422-0928-2.

- "Historical record". Fondation-monet.fr. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- Jennings, Guy (1986). Impressionist Painters. Octopus Books. ISBN 978-0-7064-2660-1.

- Gardner, Helen (1995). Art through the Ages (10th Reiss ed.). Harcourt College Pub. p. 669. ISBN 978-0-15-501141-0.

- Jennings, p. 130

- Jennings, p. 132

- "Claude Monet". Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Jennings p. 137

- Helen Gardner, Art through the Ages, p. 669

- "Arrival of the Normandy Train, Gare Saint-Lazare – The Art Institute of Chicago". artic.edu.

- "Monet's masterpiece reaches record high bid" Archived 17 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine newsfromrussia.com, 5 November 2004. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- "Virtual Monet Thumbnails Pg 1 | Special reports". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- "Monet and Others Stolen in Museum Heist in Nice". artforum.com. 8 August 2007. Retrieved 8 August 2007.

- "French police recover stolen Monet painting". artforum.com. 1 October 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- "Record Price for Monet at Auction". New York Times. 6 May 2008. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- "Le Bassin Aux Nymphéas". Christies of London. 24 June 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- "Monet work auctioned for £40.9m". BBC News. 24 June 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- Ex-Imelda Marcos aide on trial in NYC for selling Monet work. Associated Press. 17 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

Further reading

- Howard, Michael, The Treasures of Monet. (Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, 2007).

- Kendall, Richard, Monet by Himself, (Macdonald & Co 1989, updated Time Warner Books 2004), ISBN 0-316-72801-2

- Monet's years at Giverny: Beyond Impressionism. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1978. ISBN 978-0-8109-1336-3. (full text PDF available)

- Stuckey, Charles F., Monet, a retrospective, Bay Books, (1985) ISBN 0-85835-905-7

- Tucker, Paul Hayes, Monet in the '90s. (Museum of Fine Arts in association with Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1989).

- Tucker, Paul Hayes, Claude Monet: Life and Art Amilcare Pizzi, Italy 1995 ISBN 0-300-06298-2

- Tucker, Paul Hayes, Monet in the 20th century. (Royal Academy of Arts, London, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and Yale University press. 1998).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Claude Monet |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Claude Monet. |

- 48 paintings by or after Claude Monet at the Art UK site

- Claude Monet at the Museum of Modern Art

- Works by or about Claude Monet at Internet Archive

- Claude Monet, Ministère de la culture et de la communication

- Claude Monet, Joconde, Portail des collections des musées de France

- Monet at Giverny

- Union List of Artist Names, Getty Vocabularies

- Claude Monet at The Guggenheim

- Monet at Norton Simon Museum

- Impressionism: a centenary exhibition, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Monet (p. 131–167)

- Monet: The Late Years exhibition at Kimbell Art Museum

- Jennifer A. Thompson, “Railroad Bridge, Argenteuil by Claude Monet (cat. 1050),” in The John G. Johnson Collection: A History and Selected Works, a Philadelphia Museum of Art free digital publication.