Booth Tarkington

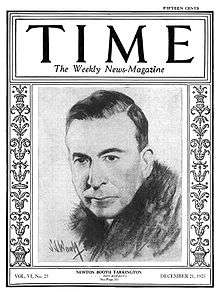

Newton Booth Tarkington (July 29, 1869 – May 19, 1946) was an American novelist and dramatist best known for his novels The Magnificent Ambersons and Alice Adams. He is one of only four novelists to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction more than once, along with William Faulkner, John Updike, and Colson Whitehead. Although he is nearly forgotten today (2020), in the 1910s and 1920s he was considered America's greatest living author.[1] Several of his stories were adapted to film. During the first quarter of the 20th century, Tarkington, along with Meredith Nicholson, George Ade, and James Whitcomb Riley helped to create a Golden Age of literature in Indiana.

Booth Tarkington | |

|---|---|

Booth Tarkington (1922) | |

| Born | Newton Booth Tarkington July 29, 1869 Indianapolis, Indiana, United States |

| Died | May 19, 1946 (aged 76) Indianapolis, Indiana, United States |

| Occupation | Novelist and dramatist |

| Years active | 1899–1946 |

Booth Tarkington served one term in the Indiana House of Representatives, was critical of the advent of automobiles, and set many of his stories in the Midwest. He eventually removed to Kennebunkport, Maine, where he continued his life work even as he suffered a loss of vision.

Biography

Booth Tarkington was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, the son of John S. Tarkington and Elizabeth Booth Tarkington. He was named after his maternal uncle Newton Booth, then the governor of California. He was also related to Chicago Mayor James Hutchinson Woodworth through Woodworth's wife Almyra Booth Woodworth.

Tarkington attended Shortridge High School in Indianapolis, and completed his secondary education at Phillips Exeter Academy, a boarding school on the East Coast.[2] He attended Purdue University for two years, where he was a member of the Sigma Chi Fraternity and the university's Morley Eating Club. He later made substantial donations to Purdue for building an all-men's residence hall, which the university named Tarkington Hall in his honor. Purdue awarded him an honorary doctorate.[3]

College years

Some of his family's wealth returned after the Panic of 1873, and his mother transferred Booth from Purdue to Princeton University. At Princeton, Tarkington is said to have been known as "Tark" among the members of the Ivy Club, the first of Princeton's historic Eating Clubs.[4] He had also been in a short-lived eating club called "Ye Plug and Ulster," which became Colonial Club.[5][6] He was active as an actor and served as president of Princeton's Dramatic Association, which later became the Triangle Club, of which he was a founding member. According to Triangle's official history,[7]

Tarkington made his first acting appearance in the club's Shakespearean spoof Katherine, one of the first three productions in the Triangle's history written and produced by students. Tarkington established the Triangle tradition, still alive today, of producing students' plays.[8] Tarkington returned to the Triangle stage as Cassius in the 1893 production of a play he co-authored, The Honorable Julius Caesar. He edited Princeton's Nassau Literary Magazine, known more recently as The Nassau Lit.[9] While an undergraduate, he socialized with Woodrow Wilson, an associate graduate member of the Ivy Club. Wilson returned to Princeton as a member of the political science faculty shortly before Tarkington departed; they maintained contact throughout Wilson's life. Tarkington failed to earn his undergraduate A.B. because of missing a single course in the classics. Nevertheless, his place within campus society was already determined, and he was voted "most popular" by the class of 1893.

Awards and recognition

In his adult life, he was twice asked to return to Princeton for the conferral of honorary degrees, an A.M. in 1899 and a Litt.D. in 1918. The conferral of more than one honorary degree on an alumnus(a) of Princeton University remains a university record.

While Tarkington never earned a college degree, he was accorded many awards recognizing and honoring his skills and accomplishments as an author. He won the Pulitzer Prize in fiction twice, in 1919 and 1922, for his novels The Magnificent Ambersons and Alice Adams. In 1921 booksellers rated him "the most significant contemporary American author" in a poll conducted by Publishers' Weekly. He won the O. Henry Memorial Award in 1931 for his short story "Cider of Normandy". His works appeared frequently on best sellers lists throughout his life. In addition to his honorary doctorate from Purdue, and his honorary masters and doctorate from Princeton, Tarkington was awarded an honorary doctorate from Columbia University, the administrator of the Pulitzer Prize, and several other universities.

Many aspects of Tarkington's Princeton years and adult life were paralleled by the later life of another writer, fellow Princetonian F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Tarkington as "The Midwesterner"

Tarkington was an unabashed Midwestern regionalist and set much of his fiction in his native Indiana. In 1902, he served one term in the Indiana House of Representatives as a Republican. Tarkington saw such public service as a responsibility of gentlemen in his socio-economic class, and consistent with his family's extensive record of public service. This experience provided the foundation for his book In the Arena: Stories of Political Life. While his service as an Indiana legislator was his only official public service position, he remained politically conservative his entire life. He supported Prohibition, opposed FDR, and worked against FDR's New Deal.

Tarkington was one of the more popular American novelists of his time. His The Two Vanrevels and Mary's Neck appeared on the annual best-seller lists a total of nine times. The Penrod novels depict a typical upper-middle class American boy of 1910 vintage, revealing a fine, bookish sense of American humor. At one time, his Penrod series was as well known as Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain. Much of Tarkington's work consists of satirical and closely observed studies of the American class system and its foibles. He himself came from a patrician Midwestern family that lost much of its wealth after the Panic of 1873. Today, he is best known for his novel The Magnificent Ambersons, which Orson Welles filmed in 1942. It is included in the Modern Library's list of top-100 novels. The second volume in Tarkington's Growth trilogy, it contrasted the decline of the "old money" Amberson dynasty with the rise of "new money" industrial tycoons in the years between the American Civil War and World War I.

Tarkington dramatized several of his novels; some were eventually filmed including Monsieur Beaucaire, Presenting Lily Mars, and The Adventures and Emotions of Edgar Pomeroy, made into a serialized film in 1920 and 1921. He also collaborated with Harry Leon Wilson to write three plays. In 1928, he published a book of reminiscences, The World Does Move. He illustrated the books of others, including a 1933 reprint of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, as well as his own. He took a close interest in fine art and collectibles, and was a trustee of the John Herron Art Institute.

Tarkington was married to Louisa Fletcher from 1902 until their divorce in 1911. Their only child, Laurel, was born in 1906 and died in 1923. He married Susanah Keifer Robinson in 1912. They had no children.[10]

Tarkington began losing his eyesight in the 1920s and was blind in his later years. He continued producing his works by dictating to a secretary. Despite his failing eyesight, between 1928 and 1940 he edited several historical novels by his Kennebunkport, Maine, neighbor Kenneth Roberts, who described Tarkington as a "co-author" of his later books and dedicated three of them (Rabble in Arms, Northwest Passage, and Oliver Wiswell) to him.

Tarkington maintained a home in his native Indiana at 4270 North Meridian in Indianapolis. From 1923 until his death,[2] Tarkington spent summers and then much of his later life in Kennebunkport at his much loved home, Seawood. In Kennebunkport he was well known as a sailor, and his schooner, the Regina, survived him. Regina was moored next to Tarkington's boathouse, The Floats which he also used as his studio. His extensively renovated studio is now the Kennebunkport Maritime Museum.[11] It was from his home in Maine that he and his wife Susannah established their relation with nearby Colby College.

Tarkington made a gift of some his papers to Princeton University, his alma mater, and his wife Susannah, who survived him by over 20 years, made a separate gift of his remaining papers to Colby College after his death. Purdue University's library holds many of his works in its Special Collection's Indiana Collection. Indianapolis commemorates his impact on literature and the theatre, and his contributions as a Midwesterner and "son of Indiana" in its Booth Tarkington Civic Theatre. He is buried in Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

Legacy

In the 1910s and 1920s, Tarkington was regarded as the great American novelist, as important as Mark Twain. His works were reprinted many times, were often on best-seller lists, won many prizes, and were adapted into other media. Penrod and its two sequels were regular birthday presents for bookish boys. By the later twentieth century, however, he was ignored in academia: no congresses, no society, no journal of Tarkington Studies. In 1985 he was cited as an example of the great discrepancy possible between an author's fame when alive and oblivion later. According to this view, if an author succeeds at pleasing his or her contemporaries — and Tarkington's works have not a whiff of social criticism — he or she is not going to please later readers of inevitably different values and concerns.[12]

In an essay titled "Hoosiers: The Lost World of Booth Tarkington", appearing in the May 2004 issue of The Atlantic, Thomas Mallon wrote of Tarkington that "only general ignorance of his work has kept him from being pressed into contemporary service as a literary environmentalist — not just a 'conservationist,' in the TR mode, but an emerald-Green decrier of internal combustion":

The automobile, whose production was centered in Indianapolis before World War I, became the snorting, belching villain that, along with soft coal, laid waste to Tarkington's Edens. His objections to the auto were aesthetic—in The Midlander (1923) automobiles sweep away the more beautifully named "phaetons" and "surreys"—but also something far beyond that. Dreiser, his exact Indiana contemporary, might look at the Model T and see wage slaves in need of unions and sit-down strikes; Tarkington saw pollution, and a filthy tampering with human nature itself. "No one could have dreamed that our town was to be utterly destroyed," he wrote in The World Does Move. His important novels are all marked by the soul-killing effects of smoke and asphalt and speed, and even in Seventeen, Willie Baxter fantasizes about winning Miss Pratt by the rescue of precious little Flopit from an automobile's rushing wheels.[13]

In June 2019, the Library of America published Booth Tarkington: Novels & Stories, collecting The Magnificent Ambersons, Alice Adams, and In the Arena: Stories of Political Life.

Bibliography

Trilogies

Penrod

- 1914: Penrod

- 1916: Penrod and Sam

- 1929: Penrod Jashber

Growth

- 1915: The Turmoil

- 1918: The Magnificent Ambersons

Winner of the 1919 Pulitzer Prize

Adapted for a 1942 film by Orson Welles and a 2002 made-for-television movie - 1923: The Midlander (re-titled National Avenue in 1927)

Novels

- 1899: The Gentleman from Indiana

- 1900: Monsieur Beaucaire

Later adapted as a play, an operetta and two films: 1924 and 1946 - 1901: Old Grey Eagle

- 1903: Cherry

Serialized in Harper's Magazine, January and February 1901 - 1902: The Two Vanrevels (1902)

- 1905: The Beautiful Lady

- 1905: The Conquest of Canaan

- 1907: The Guest of Quesnay

- 1907: His Own People

- 1909: Beasley's Christmas Party

- 1912: Beauty and the Jacobin, an Interlude of the French Revolution

- 1913: The Flirt, adapted for The Flirt (1922 film)

- 1916: Seventeen

- 1916: The Spring Concert

- 1917: The Rich Man's War

- 1919: Ramsey Milholland

- 1921: Alice Adams

Winner of the 1922 Pulitzer Prize

Adapted for film in 1923 and 1935 - 1922: Gentle Julia

Filmed in 1923 and 1936 - 1925: Women

- 1927: The Plutocrat

- 1928: Claire Ambler

- 1928: The World Does Move

- 1930: Mirthful Haven

- 1932: Mary's Neck

- 1933: Presenting Lily Mars

Adapted for film in 1943 - 1934: Rumbin Galleries (romantic novel)

- 1934: Little Orvie

- 1936: Horse and Buggy Days

Appeared in Cosmopolitan, September 1936 - 1941: The Fighting Littles

- 1941: The Heritage of Hatcher Ide

- 1943: Kate Fennigate

- 1945: Image of Josephine

- 1947: The Show Piece (posthumously published)

Short Stories

- 1919: War Stories (one of Tarkington's stories was included in this anthology)

- Miss Rennsdale Accepts )19__)

Collections

- 1904: Poe's Run: and other poems … to which is appended the book of the chronicles of the Elis (co-author, with M'Cready Sykes)

- 1921: Harlequin and Columbine

- 1923: The Fascinating Stranger and Other Stories

Non-Fiction

What the Victory Or Defeat of Germany Means to Every American (1917)

- 1905: In the Arena: Stories of Political Life

- 1926: Looking Forward, and Others

Contains "Looking Forward to the Great Adventure", "Nipskillions", "The Hopeful Pessimist", "Stars in the Dust-heap", "The Golden Age" and "Happiness Now" - The Collector's Whatnot (1923)

- Just Princeton (1924)

- The World Does Move (1929)

- 1939: Some Old Portraits (essays on 17th century artworks)

- What We've Got to Do (1942)

- Booth Tarkington On Dogs (1944)

- Your Amiable Uncle (1949)

- On Plays, Playwrights, and Playgoers (1959)

Plays

- 1908: The Man from Home (stage play co-written with Harry Leon Wilson)

- 1910: Your Humble Servant (stage play co-written with Harry Leon Wilson)

- 1919: The Gibson Upright (stage play co-written with Harry Leon Wilson)

- 1919: Clarence: A Comedy in Four Acts (stage play)[14]

- 1921: The Country Cousins: A Comedy in Four Acts (stage play)

- 1921: The Intimate Strangers: A Comedy in Three Acts (stage play)

- 1922: The Wren: A Comedy in Three Acts (stage play)

- 1922: The Ghost Story (stage play)

- 1923: The Trysting Place (stage play)

- 1926: Bimbo the Pirate (stage play)

- 1927: Station YYYY (stage play)

- 1927: The Travellers (stage play)

- 1930: 'How's Your Health? A Comedy in Three Acts (stage play)

- 1935: 'Mister Antonio: A Play in Four Acts (stage play)

References

- Gottlieb, Robert (11 November 2019). "The Rise and Fall of Booth Tarkington". The New Yorker. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Price, Nelson (2004). Indianapolis Then & Now. San Diego, California: Thunder Bay Press. p. 122. ISBN 1-59223-208-6.

- "Tarkington Hall". Purdue University. 2009-04-15. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- Rothenberg, Randall (May 4, 1991). "An Old Club Breaks Bread, and a Tradition Crumbles". The New York Times.

- Ringler, William (June 1, 1932). "Princeton Authors at the Turn of the Century". Nassau Literary Review.

- Bric a Brac Yearbook, Princeton University, 1892, listed as "N. B. Tarkington."

- "The Triangle Club, Princeton University". Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- "Triangleshow". Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- "Nassau Lit, The". Etcweb.princeton.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-04-18. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- "Booth Tarkington - Biography and Works. Search Texts, Read Online. Discuss". Online-literature.com. 2007-01-26. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- "Kennebunkport Maritime Museum/Gallery Kennebunkport Maine". Ohwy.com. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- Eisenberg, Daniel (1985). A Study of "Don Quixote". Juan de la Cuesta. p. 178. ISBN 0936388315.

- Mallon, Thomas (May 2004). "Hoosiers: The Lost World of Booth Tarkington". The Atlantic. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- "Clarence". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Booth Tarkington |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Booth Tarkington. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Booth Tarkington |

- Booth Tarkington on IMDb

- Booth Tarkington at the Internet Broadway Database

- Booth Tarkington at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Booth Tarkington at Find a Grave

- PoliticalGraveyard.com entry

- Biography from Colby College collection of his papers

- Booth Tarkington at Fantastic Fiction

- The Judy Room "Presenting Lily Mars" Section.

- Booth Tarkington Civic Theatre

- Booth Tarkington at Library of Congress Authorities, with 216 catalog records

- Finding aid to Booth Tarkington papers at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Online editions

- Works by Booth Tarkington at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Booth Tarkington at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Booth Tarkington at Internet Archive

- Works by Booth Tarkington at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)