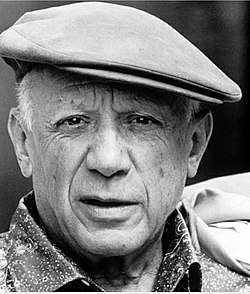

Picasso's poetry

Picasso's poetry and other written works created by Pablo Picasso, are often overlooked in discussion of his long and varied career. Despite being immersed in the literary sphere for many years, Picasso did not produce any writing himself until the age of 53. In 1935 he ceased painting, drawing and sculpting, and committed himself to the art of poetry; which in turn was briefly abandoned to focus upon singing. Although he soon resumed work in his previous fields, Picasso continued in his literary endeavours and wrote hundreds of poems, concluding with The Burial of the Count of Orgaz in 1959.[1][2]

Involvement with literature

Arriving in Paris at the dawn of the 20th century, Picasso soon met and associated with a variety of modernist writers. Poet and artist Max Jacob was one of the first friends Picasso made in Paris, and it was Jacob who helped the young artist learn French.[3] Jacob let a poverty-stricken Picasso share his room (and bed) for a period before Picasso moved to Le Bateau-Lavoir.[4][5][lower-alpha 1] Through Max Jacob, Picasso met one of the most popular members of the Parisian artistic community; writer, poet, novelist, and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, who encouraged the new-wave of artists to "innovate violently!"[6] Picasso was the focus of Apollinaire's first important works of art criticism—his 1905 pieces on Picasso also provided the artist with his earliest major coverage in the French press[7]—and Picasso highly treasured Apollinaire's gift of the original manuscript of his outrageous pornographic novel Les Onze Mille Verges, published in 1907.[8]

American art collector and writer of experimental novels, poetry and plays, Gertrude Stein was the artist's first patron.[9] Picasso attended gatherings at Stein's Paris home, with regular guests including high-profile writers such as James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald.[10]

André Salmon was another poet, art critic and writer associated with Picasso. Salmon organized the 1916 exhibition where Les Demoiselles d'Avignon was first shown.[11] The artist also collaborated with poet Pierre Reverdy,[12] with whom he later produced a book of poems Le Chant des Morts (The Song of the Dead), a response to the barbarity of war;[13] novelist and poet Blaise Cendrars;[12][lower-alpha 2] and Jean Cocteau, who wrote the scenario of the Parade ballet for which Picasso designed sets and costumes.

Photographer Brassaï, who was well acquainted with Picasso, said that no one ever witnessed the artist with a book in his hand.[15] Some who knew him said that the artist read after dark, though critic and author John Golding speculates it is more likely that Picasso "absorbed information listening to the conversation of his writer friends and other intellectuals."[16] Picasso was heavily involved with the production of literary works; over the course of his career, he illustrated around fifty books and provided maybe a hundred more with dust jackets, frontispieces and vignettes.[17]

Works 1935–1959

Early works

In 1935 Picasso's wife Olga Khokhlova left him. In the autumn he left Paris for the relative isolation of le Château de Boisgeloup in Gisors.[18] According to friend and biographer Roland Penrose, at first, Picasso did not divulge what he was jotting down in the little note-books which he hid when anyone entered the room.[19]

Some of Picasso's first poetical explorations involved the application of coloured blobs to represent objects.[19] He soon gave up this approach and focused upon words; his early attempts feature a strong use of visual images and used an idiosyncratic system of dashes of differing lengths to break the text.[19] Picasso quickly abandoned punctuation altogether, explaining to Braque:

"Punctuation is a cache-sexe which hides the private parts of literature."[20]

In a 1935 letter to her son, Picasso's mother said: "They tell me that you write. I can believe anything of you. If one day they tell me that you say mass, I shall believe it just the same."[21] That same year André Breton wrote about Picasso's poetry for the French artistic and literary journal Cahiers d'Art, wherein Breton exclaimed that: "Whole pages appear in bright variegated hues like a parrots' feathers."[22] Penrose describes how "..words have been applied as a painter uses colour from his brush."[23]

listen in your childhood to the hour that white in the blue memory borders white in her very blue eyes and piece of indigo of sky of silver the white white traverse cobalt the white paper that the blue ink tears out blueish its ultramarine descends that white enjoys blue repose agitated in the dark green wall green that writes its pleasure pale green rain that swims yellow green...[22]

-Excerpt from early Picasso poem

Over a six-week period in the spring of 1936, Picasso sent a series of letters to his "closest confidant and devoted friend",[24] poet and artist Jaime Sabartés. Penrose notes that "such frequent letter-writing was so unusual as to be disquieting, and a certain sign of restlessness."[25] On 23 April Picasso wrote to Sabartés, announcing that "from this evening, I am giving up painting, sculpture, engraving, and poetry so as to consecrate myself entirely to singing."[26] Four days later, however, Picasso wrote "I continue to work in spite of singing and all."[26]

As with his paintings, Picasso's poetry can be read and interpreted in numerous ways. The majority of his poems are untitled, and apart from the occasional mention of time and place, solely the dates are given.[27] Sabartés recalled how: "Speaking about his writings, he always tells me that what he wants is not to tell stories or to describe sensations, but to produce them with the sound of the words; not to use them as a means of expression but to let them speak for themselves as he does sometimes with colours.."[28]

Dream and Lie of Franco

The Dream and Lie of Franco is presented in a format similar to the popular Spanish strip cartoons of the period known as aleluyas. It has been called a "unique fusion of words and visual imagery".[17] Art historian Patricia Failing notes that Picasso, who had until this point never made any overtly political work, produced a work "specifically for propagandistic and fundraising purposes."[29] The Dream and Lie of Franco was intended to be sold as a series of postcards to raise funds for the Spanish Republican cause.[29][30] One of the panels portrays Franco as a "jackbooted phallus",[31] waving a sword and a flag; another depicts the dictator eating a dead horse. Other images conjured by the prose and etchings prefigure the artist's iconic Guernica – of the final four scenes in the print, three are directly linked to Picasso's Guernica studies[32] – the work concluding with animals, people, and possessions in absolute disarray.[27]

silver bells & cockle shells & guts braided in a row

a pinky in erection not a grape & not a fig..

casket on shoulders crammed with sausages & mouths

rage that contorts the drawing of a shadow that lashes teeth

nailed into sand the horse ripped open top to bottom in the sun..

cries of children cries of women cries of birds cries of flowers cries of wood and stone cries of bricks

cries of furniture of beds of chairs of curtains of casseroles of cats and papers cries of smells that claw themselves

of smoke that gnaws the neck of cries that boil in cauldron

and the rain of birds that floods the sea that eats into the bone and breaks the teeth biting

the cotton that the sun wipes on its plate that bourse and bank hide in the footprint left imbedded in the rock.

<small>Excerpts from Dream and Lie of Franco (1937)</small>

Golding suggests that: "perhaps more than any other work by Picasso, The Dream and Lie of Franco breaks down, as the Surrealists so passionately longed to, distinctions between thought, writing and visual imagery."[33] However, in his review of the etchings for The Spectator in October 1937, art historian Anthony Blunt complained that the work could not "reach more than the limited coterie of aesthetes."[34]

Plays

Picasso wrote two "surrealist" plays, Desire Caught by the Tail in the winter of 1941, followed by Les Quatre Petites Filles (The Four Little Girls) which was published in 1949. In 1952 Picasso wrote a second version of The Four Little Girls using the same title.[35] The works employ a stream of consciousness narrative style, and some critics believe that Picasso never meant for the plays to be staged, only read.[36] Desire Caught by the Tail was first performed as a reading. Jean-Paul Sartre, Valentine Hugo and Simone de Beauvoir starred alongside Picasso, while Albert Camus directed.[37] It was restaged in 1984 (with David Hockney acting) by the Guggenheim Museum.[37]

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz

Named after a painting by El Greco, and originally published in a run of 263 copies,[38] Picasso worked on El Entierro del Condo de Orgaz or The Burial of the Count of Orgaz from January 1957 to August 1959.[38] Like most of Picasso's literary output, the work defies easy categorization. The text (written in coloured chalk or pencil) does not describe the scenes depicted in the engravings.[39] Poet and friend Raphael Alberti wrote the preface for the book, stating that, "here is the inventor.. ..of great entangled poetry – Pablo plants a sketch on the surface of a page and it grows into a whole population."[40] The Burial of the Count of Orgaz is the result of the Picasso's reminiscences and reflections on his homeland of Andalusia. Earthy characters appear throughout, with names like "Don Rat" and "Don Bloodsausage".

there did finally arrive the card announcing the festivities on monday night and next

morning at dawn there were fires and worms up every ass hole and sugar palms appeared in every window

-Excerpt from The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1959)[41]

The work has been described as "among the finest expressions of unpunctuated prose that have evolved from the literary avant garde."[42]

Picasso's thoughts

- my grandmother's big balls

- are shining midst the thistles

- and where the young girls roam

- the grindstones whet their whistles

- —23 February 1955, for Don Jaime Sabartés on his saint's day[43]

- ..but what silence is louder than death says the cunt to the cunt

- while scratching the front of his anus in an elegant manner

- —Excerpt from poem of 13 October XXXVI[44]

Besides evocations of colour, sound, smell and taste; Picasso's literary works display a certain amount of fascination with sexual and scatological behaviour. Bizarre sentences appear regularly throughout, for instance: "the smell of bread crusts marinating in urine",[45] "stripped of his pants eating his bag of fries of turd"[46] "the cardinal of cock and the archbishop of gash"[43] In his study of unconscious factors in the creative process, James W. Hamilton states that some of Picasso's prose reveals "concerns with oral deprivation and immense cannibalistic rage towards the breast.."[47]

Prominent dealer and art gallery owner Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler was one of the first supporters of Pablo Picasso and the early cubists.[48] In 1959 he recalled how: "Picasso, after reading from a sketchbook containing poems in Spanish, says to me: 'Poetry – but everything you find in these poems one can also find in my paintings. So many painters today have forgotten poetry in their paintings – and it's the most important thing: poetry.'"[49]

"Poems? There are stacks of poems lying here. When I began to write them I wanted to prepare myself a palette of words, as if I were dealing with colours. All these words were weighted, filtered and appraised. I don't put much stock in spontaneous expressions of the unconscious.."[50] The artist reportedly said "that long after his death his writing would gain recognition and encyclopedias would say: 'Picasso, Pablo Ruiz – Spanish poet who dabbled in painting, drawing and sculpture.'"[51]

Criticism

In a 1935 letter to a friend Stein stated: "He writes poetry, very beautiful poetry, the sonnets of Michelangelo."[52][53] Later, however, upon meeting with the artist at a gallery, Stein's attitude had apparently changed: "..ah I said catching him by the lapels of his coat and shaking him.. ..'it is all right you are doing this to get rid of everything that has been too much for you all right all right go on doing it but don't go on trying to make me tell you it is poetry' and I shook him again."[54] Stein's partner, Alice B. Toklas wrote in May 1949: "The trouble with Picasso was that he allowed himself to be flattered into believing he was a poet too."[14]

Writer Michel Leiris compared the artist's literary output to Joyce's Finnegans Wake, stating that Picasso was: "..an insatiable player with words. [Both Joyce and Picasso] displayed an equal capacity to promote language as a real thing.. ..and to use it with as much dazzling liberty."[49]

Influence

California Poet Laureate[55] Juan Felipe Herrera was inspired to write about his youth by Picasso's Trozo de Piel or Hunk of Skin (written in Cannes on 9 January 1959),[56] the resulting work appearing in Herrera's 1998 collection of English and Spanish poems Laughing Out Loud, I Fly.[57]

Published works

- Picasso, Pablo (1968). Hunk of Skin. City Lights Books.

- Picasso, Pablo; Rothenberg, Jerome and Pierre Joris (2004). The Burial of the Count of Orgaz and Other Poems. ISBN 1878972367.

References

- Picasso, Pablo; Waldman, Anne (2004). The Burial of the Count of Orgaz and Other Poems. p. 322. ISBN 1878972367.

- Rothenberg, Jerome (1999). A Paradise of Poets: New Poems & Translations. p. 119. ISBN 0811214273.

- McNeese, Tim (2006). Pablo Picasso. p. 33. ISBN 1438106874.

- Penrose 1958, pp. 86, 87

- Jacob, Max (1991). Green, Maria (ed.). Hesitant fire: selected prose of Max Jacob. p. xvi. ISBN 0803225741.

- "Special Exhibit Examines Dynamic Relationship Between the Art of Pablo Picasso and Writing" (PDF). Yale University Art Gallery. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Golding, John (1994). Visions of the Modern. p. 11. ISBN 0520087925.

- Golding, John (1994). Visions of the Modern. p. 109. ISBN 0520087925.

- Giroud, Vincent (2006). Picasso and Gertrude Stein. p. 45. ISBN 1588392104.

- Carl Van Vechten. "Extravagant Crowd: Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas". Yale University. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Golding, John (1994). Visions of the Modern. p. 103. ISBN 0520087925.

- Penrose 1958, p. 193

- Shattuck, Kathryn (5 February 2009). "Picasso, Who Let His Imagination Run From Art to Language". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (2006). "Picasso and Hemingway: A Dud Poem and a Live Grenade". Michigan Quarterly Review. University of Michigan Library. XLV (3).

- Brassaï (1967). Picasso and Co. London, Thames and Hudson. p. 128.

- Golding, John (1994). Visions of the Modern. p. 202. ISBN 0520087925.

- Golding, John (21 November 1985). "Picasso & Poetry". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Penrose, Roland (1958). Picasso: His Life and Work. Gollancz. p. 249.

- Penrose, Roland (1958). Picasso: His Life and Work. Gollancz. p. 250.

- Sabartès (1947). Picasso: Portraits et Souvenirs. p. 125.

- Sabartès (1947). Picasso: Portraits et Souvenirs. p. 19.

- Breton, André (1935). Translated by P. S. Falla. "Picasso Poète". Cahiers d'Art. 10 (7–10): 186.

- Penrose, Roland (1958). Picasso: His Life and Work. Gollancz. p. 252.

- Penrose, Roland (1958). Picasso: His Life and Work. Gollancz. p. 253.

- Penrose, Roland (1958). Picasso: His Life and Work. Gollancz. p. 258.

- Sabartès (1947). Picasso: Portraits et Souvenirs. p. 135.

- Rothenberg, Jerome; Joris, Pierre (2004). "Pre-faces to Picasso: the Burial of the Count of Orgaz & Other Poems". Cipher Journal.

- Wynne, Frank (11 February 2013). "The Parchment Notebooks: Selected Writings by Pablo Picasso". Archived from the original on 24 April 2013.

- "Picasso's commitment to the cause". PBS.

- National Gallery of Victoria (2006). "An Introduction to Guernica". Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- O'Brian, Patrick (2012). Picasso: A Biography. p. 318. ISBN 0007466382.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Dream and Lie of Franco, 1937

- Golding, John (1994). Visions of the Modern. p. 244. ISBN 0520087925.

- Steiner, George (1987). "The Cleric of Treason". George Steiner: a reader. p. 179. ISBN 0195050681.

- Picasso, P., Rubin, W. S., & Fluegel, J. (1980). Pablo Picasso, a retrospective. New York: Museum of Modern Art. ISBN 0-87070-528-8. P. 384.

- Gates, Anita (17 October 2001). "From Picasso, Playwright: Hues of Innocence and War". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Trueman, Matt (3 October 2012). "Picasso's surreal play comes to New York". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- Fundación Picasso. "Spanish themes found in eight books illustrated by Picasso" (PDF). Translated by Meredith Hand and Jed Steiner. Revised by Laura Stratone. Documentation Center of Picasso Foundation and Birthplace Museum. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Penrose, Roland (1981). Picasso, His Life and Work. p. 462. ISBN 0520042077.

- Penrose, Roland (1981). Picasso, His Life and Work. p. 461. ISBN 0520042077.

- Rothenberg, Jerome; Picasso, Pablo (2004). The burial of the Count of Orgaz & other poems. p. 38. ISBN 1878972367.

- David Detrich. "The Burial of the Count of Orgaz". Innovative Fiction Magazine. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Rothenberg, Jerome; Picasso, Pablo (2004). The burial of the Count of Orgaz & other poems. p. 36. ISBN 1878972367.

- Rothenberg, Jerome; Picasso, Pablo (2004). The burial of the Count of Orgaz & other poems. p. 25. ISBN 1878972367.

- Rothenberg, Jerome; Picasso, Pablo (2004). The burial of the Count of Orgaz & other poems. p. 28. ISBN 1878972367.

- Rothenberg, Jerome; Picasso, Pablo (2004). The burial of the Count of Orgaz & other poems. p. 29. ISBN 1878972367.

- W. Hamilton, James (2012). A Psychoanalytic Approach to Visual Artists. p. 81. ISBN 1780490143.

- Richardson, John (1991). A Life of Picasso, The Cubist Rebel, 1907–1916. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-307-26665-1.

- "The Art in Poetry & The Poetry in Art". Getty Museum Panel. 25 April 2002. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- W. Hamilton, James (2012). A Psychoanalytic Approach to Visual Artists. pp. 81–82. ISBN 1780490143.

- Acoca, Miguel (25 October 1971). "Picasso Turns a Busy 90 Today". International Herald Tribune.

- Giroud, Vincent (2006). Picasso and Gertrude Stein. p. 44. ISBN 1588392104.

- Stein, Gertrude; van Vechten, Carl (1986). Burns, Edward (ed.). The Letters of Gertrude Stein and Carl VanVechten: 1913–1946, Volume 1. Columbia University Press. p. 449. ISBN 978-0-231-06308-1.

- Mellow, James R. (1 December 1968). "The Stein Salon Was The First Museum of Modern Art". The New York Times.

- "A totally Californian poet laureate". Los Angeles Times. 20 May 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Picasso, Pablo (1968). Hunk of Skin. City Lights Books. p. 3.

- Rose Zertuche Trevino (2006). The Pura Belpré Awards: Celebrating Latino Authors and Illustrators. p. 11. ISBN 0838935621.

Sources

Penrose, Roland (1958). Picasso: His Life and Work. Gollancz.

Notes

- Jacob was later depicted by Picasso as one of the Three Musicians

- Hemingway said of Cendrars: "When he was lying, he was more interesting than many men telling a story truly"[14]

Further reading

- Arts Council of Great Britain, Ed. Marilyn McCully (1981). A Picasso Anthology: Documents, Criticism, Reminiscences. ISBN 0728702932.

- Penrose, Roland (1981). Picasso, His Life and Work. ISBN 0520042077.

- Stein, Gertrude (1938). Picasso. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0486247155.