Max Ernst

Max Ernst (2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976) was a German (naturalised American in 1948 and French in 1958) painter, sculptor, graphic artist, and poet. A prolific artist, Ernst was a primary pioneer of the Dada movement and surrealism. He had no formal artistic training, but his experimental attitude toward the making of art resulted in his invention of frottage—a technique that uses pencil rubbings of objects as a source of images—and grattage, an analogous technique in which paint is scraped across canvas to reveal the imprints of the objects placed beneath. He is also noted for his novels consisting of collages.

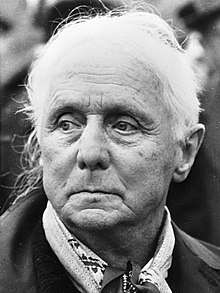

Max Ernst | |

|---|---|

Max Ernst in 1968 | |

| Born | 2 April 1891 Brühl, German Empire |

| Died | 1 April 1976 (aged 84) Paris, France |

| Nationality | German-American-French |

| Known for | painting, sculpture, poetry |

Notable work | A Week of Kindness (1934) |

| Movement | Dada, Surrealism |

| Spouse(s) | Luise Straus

( m. 1918–1927)Marie-Berthe Aurenche ( m. 1927–1942) |

Biography

Early life

Max Ernst was born in Brühl, near Cologne, the third of nine children of a middle-class Catholic family. His father Philipp was a teacher of the deaf and an amateur painter, a devout Christian and a strict disciplinarian. He inspired in Max a penchant for defying authority, while his interest in painting and sketching in nature influenced Max to take up painting.[1] In 1909 Ernst enrolled in the University of Bonn to read philosophy, art history, literature, psychology and psychiatry. He visited asylums and became fascinated with the art work of the mentally ill patients; he also started painting that year, producing sketches in the garden of the Brühl castle, and portraits of his sister and himself. In 1911 Ernst befriended August Macke and joined his Die Rheinischen Expressionisten group of artists, deciding to become an artist.

In 1912 he visited the Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne, where works by Pablo Picasso and post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin profoundly influenced him. His work was exhibited that year together with that of the Das Junge Rheinland group, at Galerie Feldman in Cologne, and then in several group exhibitions in 1913.[1] In his paintings of this period, Ernst adopted an ironic style that juxtaposed grotesque elements alongside Cubist and Expressionist motifs.[2]

In 1914 Ernst met Hans Arp in Cologne. The two became friends and their relationship lasted for fifty years. After Ernst completed his studies in the summer, his life was interrupted by World War I. Ernst was drafted and served both on the Western Front and the Eastern Fronts. The effect of the war on Ernst was devastating; in his autobiography, he wrote of his time in the army thus: "On the first of August 1914 M[ax].E[rnst]. died. He was resurrected on the eleventh of November 1918".[3] For a brief period on the Western Front, Ernst was assigned to chart maps, which allowed him to continue painting.[1] Several German Expressionist painters died in action during the war, among them August Macke and Franz Marc.

Dada and surrealism

In 1918, Ernst was demobilised and returned to Cologne. He soon married art history student Luise Straus, whom he had met in 1914. In 1919, Ernst visited Paul Klee in Munich and studied paintings by Giorgio de Chirico. The same year, inspired by de Chirico and mail-order catalogues, teaching-aide manuals and similar sources, he produced his first collages (notably Fiat modes, a portfolio of lithographs), a technique which would dominate his artistic pursuits. Also in 1919 Ernst, social activist Johannes Theodor Baargeld and several colleagues founded the Cologne Dada group. In 1919–20 Ernst and Baargeld published various short-lived magazines such as Der Strom, die Schammade and organised Dada exhibitions.[1]

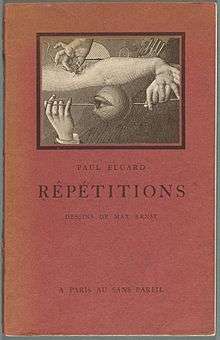

Ernst and Luise's son Ulrich 'Jimmy' Ernst was born on 24 June 1920; he also became a painter.[1] Ernst's marriage to Luise was short-lived. In 1921 he met Paul Éluard, who became a lifelong friend. Éluard bought two of Ernst's paintings (Celebes and Oedipus Rex) and selected six collages to illustrate his poetry collection Répétitions. A year later the two collaborated on Les malheurs des immortels and then with André Breton, whom Ernst met in 1921, on the magazine Littérature. In 1922, unable to secure the necessary papers, Ernst entered France illegally and settled into a ménage à trois with Éluard and his wife Gala in Paris suburb Saint-Brice, leaving behind his wife and son.[1] During his first two years in Paris, Ernst took various odd jobs to make a living and continued to paint. In 1923 the Éluards moved to a new home in Eaubonne, near Paris, where Ernst painted numerous murals. The same year his works were exhibited at Salon des Indépendants.[1]

Although apparently accepting the ménage à trois, Éluard eventually became more concerned about the affair. In 1924 he abruptly left, first for Monaco and then for Saigon.[4] He soon asked his wife and Max Ernst to join him; both had to sell paintings to finance the trip. Ernst went to Düsseldorf and sold a large number of his works to a long-time friend, Johanna Ey, owner of gallery Das Junge Rheinland.[1] After a brief time together in Saigon, the trio decided that Gala would remain with Paul. The Éluards returned to Eaubonne in early September, while Ernst followed them some months later, after exploring more of South-East Asia. He returned to Paris in late 1924 and soon signed a contract with Jacques Viot that allowed him to paint full-time. In 1925 Ernst established a studio at 22, rue Tourlaque.[1]

In 1925, Ernst invented a graphic art technique called frottage (see Surrealist techniques), which uses pencil rubbings of objects as a source of images.[5] He also created the 'grattage' technique, in which paint is scraped across canvas to reveal the imprints of the objects placed beneath. He used this technique in his famous painting Forest and Dove (as shown at the Tate Modern). The next year he collaborated with Joan Miró on designs for Sergei Diaghilev. With Miró's help, Ernst developed grattage, in which he trowelled pigment from his canvases. He also explored with the technique of decalcomania, which involves pressing paint between two surfaces.[6] Earst was also active, along with fellow Surrealists, at the Atelier 17.[7]

Ernst developed a fascination with birds that was prevalent in his work. His alter ego in paintings, which he called Loplop, was a bird. He suggested that this alter-ego was an extension of himself stemming from an early confusion of birds and humans.[8] He said that one night when he was young, he woke up and found that his beloved bird had died; a few minutes later, his father announced that his sister was born. Loplop often appeared in collages of other artists' work, such as Loplop presents André Breton. Ernst drew a great deal of controversy with his 1926 painting The Virgin Chastises the infant Jesus before Three Witnesses: André Breton, Paul Éluard, and the Painter.[9] In 1927, Ernst married Marie-Berthe Aurenche and it is thought his relationship with her may have inspired the erotic subject matter of The Kiss and other works of that year.[10] Ernst appeared in the 1930 film L'Âge d'Or, directed by the Surrealist Luis Buñuel. Ernst began to sculpt in 1934 and spent time with Alberto Giacometti. In 1938, the American heiress and artistic patron Peggy Guggenheim acquired a number of Max Ernst's works, which she displayed in her new gallery in London. Ernst and Peggy Guggenheim were married from 1942 to 1946.

World War II and later life

In September 1939, the outbreak of World War II caused Ernst to be interned as an "undesirable foreigner" in Camp des Milles, near Aix-en-Provence, along with fellow surrealist, Hans Bellmer, who had recently emigrated to Paris. He had been living with his lover and fellow surrealist painter, Leonora Carrington who, not knowing whether he would return, saw no option but to sell their house to repay their debts and leave for Spain. Thanks to the intercession of Paul Éluard and other friends, including the journalist Varian Fry, he was released a few weeks later. Soon after the German occupation of France, he was arrested again, this time by the Gestapo but managed to escape and flee to America with the help of Peggy Guggenheim and Fry.[11] Ernst and Peggy Guggenheim arrived in the United States in 1941 and were married at the end of the year.[12] Along with other artists and friends (Marcel Duchamp and Marc Chagall) who had fled from the war and lived in New York City, Ernst helped inspire the development of Abstract expressionism.

His marriage to Guggenheim did not last and in Beverly Hills, California in October 1946, in a double ceremony with Man Ray and Juliet P. Browner, he married Dorothea Tanning.[13] The couple made their home in Sedona, Arizona from 1946 to 1953, where the high desert landscapes inspired them and recalled Ernst's earlier imagery.[14] Despite the fact that Sedona was remote and populated by fewer than 400 ranchers, orchard workers, merchants and small Native American communities, their presence helped begin what would become an American artists' colony. Among the monumental red rocks, Ernst built a small cottage by hand on Brewer Road and he and Tanning hosted intellectuals and European artists such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Yves Tanguy. Sedona proved an inspiration for the artists and for Ernst, who compiled his book Beyond Painting and completed his sculptural masterpiece Capricorn while living there. As a result of the book and its publicity, Ernst began to achieve financial success. From the 1950s he lived mainly in France. In 1954 he was awarded the Grand Prize for painting at the Venice Biennale.[15] He died at the age of 84 on 1 April 1976 in Paris and was interred at Père Lachaise Cemetery.[11]

Selected works

Paintings

Early works

- Aquis Submersus (1919)

- Trophy, Hypertrophied (1919)

- Little Machine Constructed by Minimax Dadamax in Person (1919–1920)

- Murdering Airplane (1920)

- The Hat Makes the Man (1920)

- Celebes (1921)

- Oedipus Rex (1922)

First French period

- Pietà or Revolution by Night (1923)

- Saint Cecilia (1923)

- The Wavering Woman (1923)

- Ubu Imperator (1923)

- Of This Men Shall Know Nothing (1923)

- Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale (1924)

- Woman, Old Man and Flower (1924)

- Paris Dream (1924–25)

- The Blessed Virgin Chastises the Infant Jesus Before Three Witnesses: A.B., P.E. and the Artist (1926)

- Forest series, e.g. Forest and Dove (1927), The Wood (1927)

- Rendezvous of Friends – The Friends Become Flowers (1928)

- Loplop series, e.g. Loplop Introduces Loplop (1930), Loplop Introduces a Young Girl (1930)

- City series, e.g. Petrified City (1933), Entire City (1935–36, two versions)

- Garden Aeroplane Trap series (1935–36)

- The Joy of Living (1936)

- The Nymph Echo (1936)

- The Fireside Angel (1937)

- The Barbarians (1937)

- The Fascinating Cypress (1940)

- The Robing of the Bride (1940)

American period

- Totem and Taboo (1941)

- Marlene (1941)

- Napoleon in the Wilderness (1941)

- Day and Night (1941–42)

- The Antipope (1942)

- Europe After the Rain II (1940–42)

- Surrealism and Painting (1942)

- Vox Angelica (1943)

- Everyone Here Speaks Latin (1943)

- Painting for Young People (1943)

- The Eye of Silence (1944)

- Dream and Revolution (1945)

- The Temptation of Saint Anthony (1945)

- The Phases of the Night (1946)

- Design in Nature (1947)

- A beautiful day (1948), featured in the Painting toward architecture exhibition (1947-52)[16]

- Inspired Hill (1950)

- Colorado of Medusa, Color-Raft of Medusa (1953)

Second French period

- Mundus est fabula (1959)

- The Garden of France (1962)

- The Sky Marries the Earth (1964)

- The World of the Naive (1965)

- Ubu, Father and Son (1966)

- Birth of a Galaxy (1969)

- "La dernière forêt" (The last forest) (1960–1970)

Collages, lithographs, drawings, illustrations, etc.

- Fiat modes (1919, portfolio of lithographs)

- Illustrations for books by Paul Éluard: Répétitions (1922), Les malheurs des immortels (1922), Au défaut du silence (1925)

- Histoire Naturelle (1926, frottage drawings)

- La femme 100 têtes (1929, graphic novel)

- Rêve d'une petite fille qui voulut entrer au carmel (1930, graphic novel)

- Une Semaine de Bonté (1934, graphic novel)

- Paramythes (1949, collages with poems)

- Illustrations for editions of works by Lewis Carroll: Symbolic Logic (1966, under the title Logique sans peine), The Hunting of the Snark (1968), and Lewis Carrols Wunderhorn (1970, an anthology of texts)

- Deux Oiseaux (1970, lithograph in colours)

- Aux petits agneaux (1971, lithographs)

- Paysage marin avec capucin (1972, illustrated book with essays by various authors)

- Maximiliana: the illegal practice of astronomy : hommage à Dorothea Tanning (1974, art book)

- Oiseaux en peril (1975, etchings with aquatint in colours; published posthumously)

Sculptures

- Bird (c. 1924)

- Habakuk (1934)

- Oedipus (1934, two versions)

- Moonmad (1944)

- An Anxious Friend (1944)

- Capricorn (1948)

- The King Playing with the Queen (1954)

- Two and Two Make One (1956)

- Immortel (1966–67)

- The Assistant, The Frog and The Tortoise (1967)

Ernst in modern culture

- Many of Ernst's works from Une Semaine de Bonté are used in albums by American rock group The Mars Volta. Also, Barefoot in the Head, a collaboration between guitarist Thurston Moore and saxophonists Jim Sauter and Don Dietrich of Borbetomagus, features a collage from this same book.

- American rock group Mission of Burma titled two songs after the artist: "Max Ernst" was the b-side of their first 1980 single (now included on the CD of Signals, Calls and Marches), mentioning two of Ernst's paintings (The Blessed Virgin Chastises the Infant Jesus and Garden Airplane-Trap) and ending with the words "Dada dada dada ..." repeated many times and distorted via tape loop; their 2002 album OnOffOn features "Max Ernst's Dream".

- Writer J. G. Ballard makes numerous references to the art works of Max Ernst in his breakthrough novel The Drowned World (1962) and the experimental collection of short stories The Atrocity Exhibition (1970).

- Europe After the Rain was used by musician John Foxx as the title for the opening track of his 1981 album The Garden.

- Max Ernst himself, and some of his work, is mentioned in William Gibson's novel Count Zero (1986), the second novel of the Sprawl trilogy, an influential set of books which established the cyberpunk subgenre of science-fiction

- (The) Eye of Silence was used by musician Cavestar (Kevin Crosslin) as the title of a track from his 1997 album Cavestar.

- The first edition of the Penguin paperback edition of James Blish's A Case of Conscience uses details from The Eye of Silence as cover art.

- Ernst's alter-ego Loplop appears in China Miéville's 1998 debut novel King Rat, the Garden Aeroplane Trap also (literally) appears in Mievielle's "The Last Days of New Paris" .

- German experimental electronic musician Thomas Brinkmann has made numerous references to Max Ernst and Loplop in his productions and record labels.

Legacy

Max Ernst's life and career are examined in Peter Schamoni's 1991 documentary Max Ernst. Dedicated to the art historian Werner Spies, it was assembled from interviews with Ernst, stills of his paintings and sculptures, and the memoirs of his wife Dorothea Tanning and son Jimmy. The 101-minute German film was released on DVD with English subtitles by Image Entertainment.

In 2005, "Max Ernst: A Retrospective" opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and included works such as Celebes (1921), Ubu Imperator (1923), and Fireside Angel (1937), which is one of the few definitively political pieces and is sub-titled The Triumph of Surrealism depicting a raging bird-like creature that symbolises the wave of fascism that enveloped Europe. The exhibition also includes Ernst's works that experiment with free association writing and the techniques of frottage, created from a rubbing from a textured surface; grattage, involving scratching at the surface of a painting; and decalcomania, which involves altering a wet painting by pressing a second surface against it and taking it away.[17]

Ernst's son Jimmy, a well-known German/American abstract expressionist painter, who lived on the south shore of Long Island, died in 1984. His memoirs, A Not-So-Still Life, were published shortly before his death. Max Ernst's grandson Eric and his granddaughter Amy are both artists and writers.

See also

Notes

- Spies, Rewald 2005, 285–286.

- Spies et al. 1991, p. 56.

- Spies, Rewald 2005, xiv.

- Warlick, M.E. 2001. Max Ernst and Alchemy: a Magician in Search of Myth, p. 83. ISBN 978-0-292-79136-7

- Spies et al. 1991, p. 128.

- Max Ernst working in decalcomania is shown in the 1978 documentary on the Dada and Surrealist art movement, Europe After the Rain.

- "Atelier 17: Europe and the Early Years". Swann Galleries News. 10 October 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Spies et al. 1991, p. 285.

- Image: The Blessed Virgin Chastises the Infant Jesus Before Three Witnesses: A.B., P.E. and the Artist

- Flint, Lucy, Guggenheim Collection. "The Kiss (Le Baiser)". Archived from the original on 6 July 2015.

- Olga's Gallery. "Max Ernst biography".

- Iyengar, Rishi (6 April 2015). "New Google Doodle Honors Surrealist Painter Leonora Carrington". Time. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Flint, Peter B. (21 January 1991). "Juliet Man Ray, 79, The Artist's Model And Muse, Is Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- Waldman, Diane (1975). Max Ernst : A Retrospective. New York, NY: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

- "Max Ernst 1891–1976". Tate Etc.

- (March 15, 2019). Max Ernst. A beautiful day, (1948). artdesigncafe.com. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- "A Max Ernst Retrospective Opens Today in NY". Art+Auction. 7 April 2005. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

References

- Spies, Werner, Karin von Maur, Sigrid Metken, Uwe M. Schneede, Sarah Wilson, and Max Ernst. 1991. Max Ernst: A Retrospective. Munchen: Prestel. ISBN 1854370693

- Werner Spies & Sabine Rewald (eds.), Max Ernst: A Retrospective. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art / New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005. Catalogue of exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York: Max Ernst: a retrospective

- John Russell. Max Ernst: life and work (New York, H.N. Abrams, 1967) OCLC 2034599

- Bodley Gallery (New York, N.Y.) Max Ernst : paintings, collages, drawings, sculpture : October 30 – November 25, 1961 : Bodley Gallery, 223 East 60, New York (exhibition catalogue and commentary; published by the gallery, 1961) OCLC 54157692

- Max Ernst Books and Graphic Works. Institut fur Auslandsbeziehungen, 1977.

- Elizabeth Legge. Max Ernst: The Psychoanalytic Sources (UMI, 1989).

- David Hopkins. Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst: The Bride Shared (Oxford, 1998).

- William Camfield. Max Ernst Dada and the Dawn of Surrealism (MoMA, 1993).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Max Ernst. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Max Ernst |

- Max Ernst at the Museum of Modern Art

- Max Ernst on Wikiart.org

- Max Ernst, A Retrospective, The Metropolitain Museum of Art

- Paintings in Museums and Public Art Galleries Worldwide, Artcyclopedia

- Works in the National Galleries of Scotland

- Max Ernst gallery

- Artfacts.Net, Max Ernst facts

- Max Ernst in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website