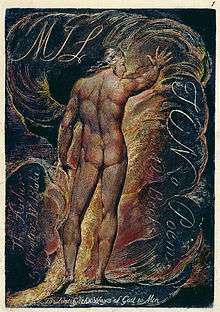

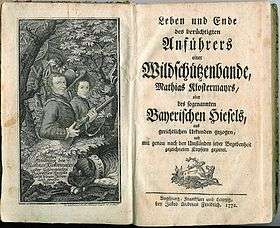

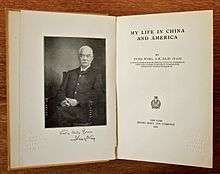

Book frontispiece

A frontispiece in books is a decorative or informative illustration facing a book's title page—on the left-hand, or verso, page opposite the right-hand, or recto, page.[1] In some ancient editions or in modern luxury editions the frontispiece features thematic or allegorical elements, in others is the author's portrait that appears as the frontispiece. In medieval illuminated manuscripts, a presentation miniature showing the book or text being presented (by whom and to whom varies) was often used as a frontispiece.

Origin

The word comes from the French frontispice, which derives from the late Latin frontispicium,[2] composed of the Latin frons ('forehead') and specere ('to look at'). It was synonymous with 'metoposcopy'. In English, it was originally used as an architectural term, referring to the decorative facade of a building. In the 17th century, in other languages as in Italian,[3] the term came to refer to the title page of a book, which at the time was often decorated with intricate engravings that borrowed stylistic elements from architecture, such as columns and pediments.

Over the course of the 17th century, the title page of a book came to be accompanied by an illustration on the facing page (known in Italian as antiporta), so that in English the term took on the meaning it retains today as early as 1682. By then, the English spelling had also morphed, by way of folk etymology, from 'frontispice' to 'frontispiece' ('front' + 'piece').[4]

See also

References

- Franklin H. Silverman, Self-Publishing Textbooks and Instructional Materials, Ch. 9, Atlantic Path Publishing, 2004.

- Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1855). "On False Etymologies". Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 68–69.

- Since 1619. Cf. Cortelazzo, Manlio; Zolli, Paolo (1980). Dizionario etimologico della lingua italiana (in Italian). II. Bologna: Zanichelli. p. 461.

- Michael Quinion, World Wide Words Entry

External links

| Look up frontispiece in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on book frontispieces