David Hockney

David Hockney, OM, CH, RA (born 9 July 1937) is an English painter, draftsman, printmaker, stage designer, and photographer. As an important contributor to the pop art movement of the 1960s, he is considered one of the most influential British artists of the 20th century.[2][3]

David Hockney OM CH RA | |

|---|---|

| Born | 9 July 1937 Bradford, West Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Bradford School of Art (1953–1958) Royal College of Art (1959–1962) |

| Known for | Painting, printmaking, photography, set design |

Notable work | A Bigger Splash Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) Peter Getting Out of Nick's Pool American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman) Bigger Trees Near Warter A Bigger Grand Canyon Garrowby Hill A Bigger Interior with Blue Terrace and Garden 2017 |

| Movement | Pop art |

| Awards | John Moores Painting Prize (1967) Companion of Honour (1997) Royal Academician Order of Merit 2012; Honorary Doctorate, Otis College of Art and Design, 1985[1] |

Hockney has owned a home and studio in Bridlington and London, and two residences in California, where he has lived on and off since 1964: one in the Hollywood Hills, one in Malibu, and an office and archives on Santa Monica Boulevard[4] in West Hollywood, California.[5][6][7]

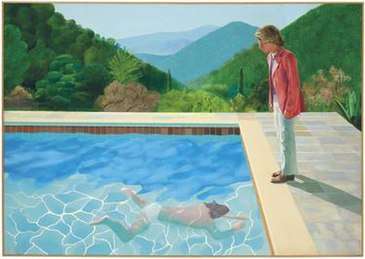

On 15 November 2018, Hockney's 1972 work Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) sold at Christie's auction house in New York City for $90 million (£70 million), becoming the most expensive painting by a living artist sold at auction.[8][9][10] This broke the previous record, set by the 2013 sale of Jeff Koons' Balloon Dog (Orange) for $58.4 million.[11] Hockney held this record until 15 May 2019, Jeff Koons reclaimed the honour when his Rabbit sold for more than $91 million at Christie's in New York.[12]

Biography

Hockney was born in Bradford, West Riding of Yorkshire, England, to Laura and Kenneth Hockney (a conscientious objector in the Second World War), the fourth of five children.[13][14] He was educated at Wellington Primary School, Bradford Grammar School, Bradford College of Art (where his teachers included Frank Lisle[15] and his fellow students included Derek Boshier, Pauline Boty, Norman Stevens, David Oxtoby and John Loker[16][17][18]) and the Royal College of Art in London, where he met R. B. Kitaj.[13] While there, Hockney said he felt at home and took pride in his work.

At the Royal College of Art, Hockney featured in the exhibition Young Contemporaries – alongside Peter Blake – that announced the arrival of British Pop art. He was associated with the movement, but his early works display expressionist elements, similar to some works by Francis Bacon. When the RCA said it would not let him graduate if he did not complete an assignment of a life drawing of a female model in 1962, Hockney painted Life Painting for a Diploma in protest. He had refused to write an essay required for the final examination, saying he should be assessed solely on his artworks. Recognising his talent and growing reputation, the RCA changed its regulations and awarded the diploma. After leaving the RCA, he taught at Maidstone College of Art for a short time.[19]

Hockney moved to Los Angeles in 1964, where he was inspired to make a series of paintings of swimming pools in the comparatively new acrylic medium using vibrant colours. The artist lived back and forth among Los Angeles, London, and Paris in the late 1960s to 1970s. In 1974 he began a decade-long personal relationship with Gregory Evans who moved with him to the US in 1976 and as of 2019 remains a business partner.[20] In 1978 he rented a house in the Hollywood Hills, and later bought and expanded it to include his studio.[21] He also owned a 1,643-square-foot beach house at 21039 Pacific Coast Highway in Malibu, which he sold in 1999 for around $1.5 million.[22]

Work

Hockney has experimented with painting, drawing, printmaking, watercolours, photography, and many other media including a fax machine, paper pulp, and computer and iPad drawing programs.[23] The subject matter of interest ranges from still lifes to landscapes, portraits of friends, his dogs, and stage designs for the Royal Court Theatre, Glyndebourne, and the Metropolitan Opera in New York City.

Portraits

Hockney has always returned to painting portraits throughout his career. From 1968, and for the next few years, he painted portraits and double portraits of friends, lovers, and relatives just under life-size in a realistic style that adroitly captured the likenesses of his subjects.[24] Hockney has repeatedly been drawn to the same subjects – his family, employees, artists Mo McDermott and Maurice Payne, various writers he has known, fashion designers Celia Birtwell and Ossie Clark (Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy, 1970–71), curator Henry Geldzahler, art dealer Nicholas Wilder,[25] George Lawson and his ballet dancer lover, Wayne Sleep, and also his romantic interests throughout the years including Peter Schlesinger and Gregory Evans.[26] Perhaps more than all of these, Hockney has turned to his own figure year after year, creating over 300 self-portraits.[27]

From 1999 to 2001 Hockney used a camera lucida for his research into art history as well as his own work in the studio.[28][29] He created over 200 drawings of friends, family, and himself using this antique lens-based device.

In 2016, the Royal Academy exhibited Hockney's series entitled 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life which traveled to Ca' Pesaro in Venice, Italy, and the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, in 2017 and to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2018. Hockney calls the paintings started in 2013 "twenty-hour exposures" because each sitting took six to seven hours on three consecutive days.[30]

Printmaking

Hockney experimented with printmaking as early as a lithograph Self-Portrait in 1954 and worked in etchings during his time at RCA.[31] In 1965, the print workshop Gemini G.E.L. approached him to create a series of lithographs with a Los Angeles theme. Hockney responded by creating The Hollywood Collection, a series of lithographs recreating the art collection of a Hollywood star, each piece depicting an imagined work of art within a frame. Hockney went on to produce many other portfolios with Gemini G.E.L. including Friends, The Weather Series, and Some New Prints.[32] During the 1960s he produced several series of prints he thought of as 'graphic tales', including A Rake’s Progress (1961–63)[33] after Hogarth, Illustrations for Fourteen Poems from C.P. Cavafy (1966)[34] and Illustrations for Six Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm (1969).[35][31]

In 1973 Hockney began a fruitful collaboration with Aldo Crommelynck, Picasso's preferred printer. In his atelier, he adopted Crommelynck's trademark sugar lift, as well as a system of the master's own devising of imposing a wooden frame onto the plate to ensure color separation. Their early work together included Artist and Model (1973–74) and Contrejour in the French Style (1974).[31] In 1976 Hockney created a portfolio of 20 etchings at Crommelynck's atelier, The Blue Guitar: Etchings By David Hockney Who Was Inspired By Wallace Stevens Who Was Inspired By Pablo Picasso.[36] The etchings refer to themes in a poem by Wallace Stevens, "The Man with the Blue Guitar". It was published by Petersburg Press in October 1977. That year, Petersburg also published a book, in which the images were accompanied by the poem's text.[37]

In the summer of 1978, David Hockney stayed 6 weeks with his friend the printer Ken Tyler. Tyler invited Hockney to try a new technique with liquid paper. The process is painting with the paper itself, so the artist had to do it himself by hand. Each image becomes a unique work between printmaking and painting. In 6 weeks, Hockney created a total of 29 artworks with a series of 17 sunflowers and swimming pools.[38]

Some of Hockney's other print portfolios include Home Made Prints (1986),[39] Recent Etchings (1998) and Moving Focus (1984–1986),[40] which contains lithographs related to A Walk Around the Hotel Courtyard, Acatlan. A retrospective of his prints, including 'computer drawings' printed on fax machines and inkjet printers, was exhibited at Dulwich Picture Gallery in London 5 February – 11 May 2014 and Bowes Museum, County Durham 7 June – 28 September 2014, with an accompanying publication Hockney, Printmaker by Richard Lloyd.[31]

Photocollages

In the early 1980s, Hockney began to produce photo collages—which in his early explorations within his personal photo albums he referred to as "joiners"[41]—first using Polaroid prints and subsequently 35mm, commercially processed colour prints. Using Polaroid snaps or photolab-prints of a single subject, Hockney arranged a patchwork to make a composite image.[42] Because the photographs are taken from different perspectives and at slightly different times, the result is work that has an affinity with Cubism, one of Hockney's major aims—discussing the way human vision works. Some pieces are landscapes, such as Pearblossom Highway #2,[2][43] others portraits, such as Kasmin 1982,[44] and My Mother, Bolton Abbey, 1982.[45]

Creation of the "joiners" occurred accidentally. He noticed in the late sixties that photographers were using cameras with wide-angle lenses. He did not like these photographs because they looked somewhat distorted. While working on a painting of a living room and terrace in Los Angeles, he took Polaroid shots of the living room and glued them together, not intending for them to be a composition on their own. On looking at the final composition, he realised it created a narrative, as if the viewer moved through the room. He began to work more with photography after this discovery and stopped painting for a while to exclusively pursue this new technique. Frustrated with the limitations of photography and its 'one-eyed' approach, however,[46] he returned to painting.

Other technology

In December 1985 Hockney used the Quantel Paintbox, a computer program that allowed the artist to sketch directly onto the screen. The resulting work was featured in a BBC series that profiled several artists.

Since 2009, Hockney has painted hundreds of portraits, still lifes and landscapes using the Brushes iPhone[47] and iPad[48] application, often sending them to his friends.[48] In 2010 and 2011, Hockney visited Yosemite National Park to draw its landscape on his iPad.[49] He used an iPad in designing a stained glass window at Westminster Abbey which celebrated the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. Unveiled in September 2018, the Queen's Window is located in the north transept of the Abbey and features a hawthorn blossom scene which is set in Yorkshire.[50]

From 2010 to 2014, Hockney created multi-camera movies using three to eighteen cameras to record a single scene. He filmed the landscape of Yorkshire in various seasons, jugglers and dancers, and his own exhibitions within the de Young Museum and the Royal Academy of Arts.[51]

Hockney's earlier photocollages influenced his shift to another medium, digital photography. He combined hundreds of photographs to create multi-viewpoint "photographic drawings" of groups of his friends in 2014.[52] Hockney picked the process back up in 2017, this time using the more advanced Agisoft PhotoScan photogrammetric software which allowed him to stitch together and rearrange thousands of photos. The resulting images were printed out as massive photomurals and were exhibited at Pace Gallery and LACMA in 2018.[53]

Plein air landscapes

Hockney returned more frequently to Yorkshire in the 1990s, usually every three months, to visit his mother[54] who died in 1999. He rarely stayed for more than two weeks until 1997,[54] when his friend Jonathan Silver who was terminally ill encouraged him to capture the local surroundings. He did this at first with paintings based on memory, some from his boyhood. In 1998, he completed the painting of the Yorkshire landmark, Garrowby Hill.[55] Hockney returned to Yorkshire for longer and longer stays, and by 2003 was painting the countryside en plein air in both oils and watercolor.[54] He set up residence and studio in a converted bed and breakfast, in the seaside town of Bridlington, about 75 miles from where he was born.[56] The oil paintings he produced after 2005 were influenced by his intensive studies in watercolour, a series titled Midsummer: East Yorkshire (2003–2004).[57] He created paintings made of multiple smaller canvases—two to fifty—placed together. To help him visualize work at that scale, he used digital photographic reproductions to study the day's work.[54]

In June 2007, Hockney's largest painting, Bigger Trees Near Warter or/ou Peinture sur le Motif pour le Nouvel Age Post-Photographique, which measures 15 feet by 40 feet, was hung in the Royal Academy's largest gallery in its annual Summer Exhibition.[58] This work "is a monumental-scale view of a coppice in Hockney's native Yorkshire, between Bridlington and York. It was painted on 50 individual canvases, mostly working in situ, over five weeks last winter."[59] In 2008, he donated it to Tate in London, saying: "I thought if I'm going to give something to the Tate I want to give them something really good. It's going to be here for a while. I don't want to give things I'm not too proud of ... I thought this was a good painting because it's of England ... it seems like a good thing to do."[60] The painting was the subject of a BBC1 Imagine film documentary by Bruno Wollheim called David Hockney: A Bigger Picture (2009) which followed Hockney as he worked outdoors over the preceding two years.[61]

Theatre works

Hockney's first stage designs were for Ubu Roi at London's Royal Court Theatre in 1966,[62] Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress at the Glyndebourne Festival Opera in England in 1975, and The Magic Flute for Glyndebourne in 1978.[63] In 1980, he agreed to design sets and costumes for a 20th-century French triple bill at the Metropolitan Opera House with the title Parade. The works were Parade, a ballet with music by Erik Satie; Les mamelles de Tirésias, an opera with libretto by Guillaume Apollinaire and music by Francis Poulenc, and L'enfant et les sortilèges, an opera with libretto by Colette and music by Maurice Ravel.[64] The reimagined set of L'enfant et les sortilèges from the 1983 exhibition Hockney Paints the Stage is a permanent installation at the Spalding House branch of the Honolulu Museum of Art. He designed sets for another triple bill of Stravinsky's Le sacre du printemps, Le rossignol, and Oedipus Rex for the Metropolitan Opera in 1981[65] as well as Richard Wagner's Tristan und Isolde for the Los Angeles Music Center Opera in 1987,[66] Puccini's Turandot in 1991 at the Chicago Lyric Opera, and Richard Strauss's Die Frau ohne Schatten in 1992 at the Royal Opera House in London.[63] In 1994, he designed costumes and scenery for twelve opera arias for the TV broadcast of Plácido Domingo's Operalia in Mexico City. Technical advances allowed him to become increasingly complex in model-making. At his studio he had a proscenium opening 6 feet (1.8 m) by 4 feet (1.2 m) in which he built sets in 1:8 scale. He also used a computerised setup that let him punch in and program lighting cues at will and synchronise them to a soundtrack of the music.[63]

In 2017, Hockney was awarded the San Francisco Opera Medal on the occasion of the revival and restoration of his production for Turandot.[67]

The majority of Hockney's theater works and stage design studies are found in the collection of The David Hockney Foundation.[68]

Exhibitions

David Hockney has been featured in over 400 solo exhibitions and over 500 group exhibitions.[69] He had his first one-man show at Kasmin Limited when he was 26 in 1963, and by 1970 the Whitechapel Gallery in London had organised the first of several major retrospectives, which subsequently travelled to three European institutions.[70] LACMA also hosted a retrospective exhibition in 1988 which travelled to The Met, New York, and Tate, London. In 2004, he was included in the cross-generational Whitney Biennial, where his portraits appeared in a gallery with those of a younger artist he had inspired, Elizabeth Peyton.[5]

In October 2006, the National Portrait Gallery in London organised one of the largest ever displays of Hockney's portraiture work, including 150 paintings, drawings, prints, sketchbooks, and photocollages from over five decades. The collection ranged from his earliest self-portraits to work he completed in 2005. Hockney assisted in displaying the works and the exhibition, which ran until January 2007, was one of the gallery's most successful. In 2009, "David Hockney: Just Nature" attracted some 100,000 visitors at the Kunsthalle Würth in Schwäbisch Hall, Germany.[54]

From 21 January 2012 to 9 April 2012, the Royal Academy presented A Bigger Picture,[71] which included more than 150 works, many of which take entire walls in the gallery's brightly lit rooms. The exhibition is dedicated to landscapes, especially trees and tree tunnels of his native Yorkshire.[72] Works included oil paintings, watercolours, and drawings created on an iPad[73] and printed on paper. Hockney said, in a 2012 interview, "It's about big things. You can make paintings bigger. We're also making photographs bigger, videos bigger, all to do with drawing."[74] The exhibition drew more than 600,000 visitors in under 3 months.[75] The exhibition moved to the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain from 15 May to 30 September, and from there to the Ludwig Museum in Cologne, Germany, between 27 October 2012 and 3 February 2013.[76]

From 26 October 2013 to 30 January 2014 David Hockney: A Bigger Exhibition was presented at the de Young Museum, one of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.[77] The largest solo exhibition Hockney has had, with 397 works of art in more than 18,000 square feet, was curated by Gregory Evans and included the only public showing of The Great Wall, developed during research for Secret Knowledge, and works from 1999 to 2013 in a variety of media from camera lucida drawings to watercolors, oil paintings, and digital works.

From 9 February to 29 May 2017 David Hockney was presented at the Tate Britain, becoming the gallery's most visited exhibition ever.[78] The exhibition marked Hockney's 80th year and gathered together "an extensive selection of David Hockney’s most famous works celebrating his achievements in painting, drawing, print, photography and video across six decades". The show then traveled to Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and The Metropolitan Museum of Art.[79][80][81] The wildly popular retrospective landed among the top ten ticketed exhibitions in London and Paris for 2017 with over 4,000 visitors per day at the Tate and over 5,000 visitors per day in Paris.[82]

After the blockbuster exhibitions in 2017 of the works of decades past, Hockney moved right along to show his newest paintings on hexagonal canvases and mural-size 3D photographic drawings at Pace Gallery in 2018.[83] He revisited paintings of Garrowby Hill, the Grand Canyon, and Nichols Canyon Road, this time painting them on hexagonal canvases to enhance aspects of reverse perspective.[84] In 2019, his early work featured in his native Yorkshire at The Hepworth Wakefield.[85]

Personal life

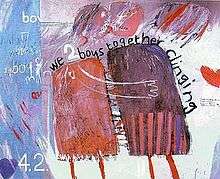

Hockney is gay[86] and has explored the nature of gay love in his portraiture. Sometimes, as in We Two Boys Together Clinging (1961), named after a poem by Walt Whitman, the works refer to his love for men. In 1963, he painted two men together in the painting Domestic Scene, Los Angeles, one showering while the other washes his back.[26] In summer 1966, while teaching at UCLA he met Peter Schlesinger, an art student who posed for paintings and drawings, and with whom he became romantically involved.[87]

On the morning of 18 March 2013, Hockney's 23-year-old assistant, Dominic Elliott, died as a result of drinking drain cleaner at Hockney's Bridlington studio; he had also earlier drunk alcohol and taken cocaine, ecstasy and temazepam. Elliott was a first- and second-team player for Bridlington Rugby Club. It was reported that Hockney's partner drove Elliott to Scarborough General Hospital where he later died. The inquest returned a verdict of death by misadventure and Hockney was never implicated.[88][89][90] In November 2015 Hockney sold his house in Bridlington, a five-bedroomed former guest house, for £625,000, cutting all his remaining ties with the town.[91][92]

He holds a California Medical Marijuana Verification Card, which enables him to buy cannabis for medical purposes. He has used hearing aids since 1979, but realised he was going deaf long before that.[93] He keeps fit by spending half an hour in the swimming pool each morning,[94] and can stand for six hours at the easel.[90]

Hockney has synaesthetic associations between sound, colour and shape.[95]

Collections

Many of Hockney's works are housed in Salts Mill, in Saltaire, near his hometown of Bradford. Another large group of works are held by The David Hockney Foundation. His work is in numerous public and private collections worldwide, including:

- Honolulu Museum of Art

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

- Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark

- Art Institute of Chicago

- National Portrait Gallery, London

- Tate, U.K.

- J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Museum of Modern Art, New York

- Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

- Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo

- Aboa Vetus & Ars Nova, Turku, Finland

- Mumok, Ludwig Foundation, Vienna

- Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

- Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.[57]

- Muscarelle Museum of Art, Williamsburg, VA[96]

Recognition

In 1967, Hockney's painting, Peter Getting Out of Nick's Pool, won the John Moores Painting Prize at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. Hockney was offered a knighthood in 1990 but declined, before accepting an Order of Merit in January 2012.[97][98] He was awarded The Royal Photographic Society's Progress medal in 1988[99] and the Special 150th Anniversary Medal and Honorary Fellowship in recognition of a sustained, significant contribution to the art of photography in 2003.[100][101] He was made a Companion of Honour in 1997[102] and awarded The Cultural Award from the German Society for Photography (DGPh).[103] He is a Royal Academician.[104] In 2012, Queen Elizabeth II appointed him to the Order of Merit, an honour restricted to 24 members at any one time for their contributions to the arts and sciences.[56]

He was a Distinguished Honoree of the National Arts Association, Los Angeles, in 1991 and received the First Annual Award of Achievement from the Archives of American Art, Los Angeles, in 1993. He was appointed to the Board of Trustees of the American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, New York in 1992 and was given a Foreign Honorary Membership to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1997. In 2003, Hockney was awarded the Lorenzo de' Medici Lifetime Career Award of the Florence Biennale, Italy.[105]

Commissioned by The Other Art Fair, a November 2011 poll of 1,000 British painters and sculptors declared him Britain's most influential artist of all time.[106] In 2012, Hockney was among the British cultural icons selected by artist Sir Peter Blake to appear in a new version of his most famous artwork – the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover – to celebrate the British cultural figures of his life that he most admires.[107][108]

Art market

In 1963, Hockney was first represented by art dealer John Kasmin. He is, as of 2018, represented by Annely Juda Fine Art, London; Pace Gallery, New York; L.A. Louver, Venice, CA;[109] and Galerie Lelong, Paris. On 21 June 2006, Hockney's painting, The Splash sold for £2.6 million.[110] It was offered for auction again on 11 February 2020, with an estimate of £20-30 million[111] and sold, to an unknown buyer, for £23.1 million.[112]

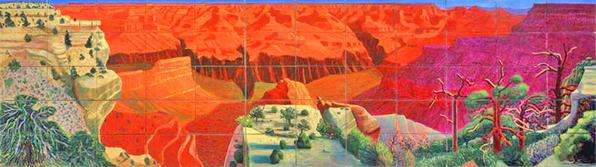

His A Bigger Grand Canyon, a series of 60 canvases that combined to produce one enormous picture, was bought by the National Gallery of Australia for $4.6 million.

Beverly Hills Housewife (1966–67), a 12-foot-long acrylic that depicts the collector Betty Freeman standing by her pool in a long hot-pink dress, sold for $7.9 million at Christie's in New York in 2008, the top lot of the sale and a record price for a Hockney.[5] This was topped in 2016 when his Woldgate Woods landscape made £9.4 million at auction.[113]

The record was broken again in 2018 with the sale of Piscine de Medianoche (Paper Pool 30) for $11.74 million and then doubled in the same Sotheby's auction when Pacific Coast Highway and Santa Monica sold for $28.5 million.[114]

On 15 November 2018, David Hockney's 1972 painting Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) sold at Christie's for $90.3 million with fees, surpassing the previous auction record for a living artist of $58.4 million, held by Jeff Koons for one of his Balloon Dog sculptures.[115] He had originally sold this painting for $20,000 in 1972.[9]

The Hockney–Falco thesis

In the 2001 television programme and book, Secret Knowledge, Hockney posited that the Old Masters used camera obscura as well as camera lucida and lens techniques that projected the image of the subject onto the surface of the painting. Hockney argues that this technique migrated gradually from Northern Europe to Italy, and is the reason for the photographic style of painting we see in the Renaissance and later periods of art. He published his conclusions in the 2001 book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, which was revised in 2006.[5]

Public life

Like his father, Hockney was a conscientious objector, and worked as a medical orderly in hospitals during his National Service, 1957–1959.[116]

Hockney was a founder of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in 1979.[21] He serves on the advisory board of the political magazine Standpoint,[117] and contributed original sketches for its launch edition, in June 2008.[118]

He is a staunch pro-tobacco campaigner and was invited to guest-edit BBC Radio's Today programme on 29 December 2009 to air his views on the subject.[119]

In October 2010, he and a hundred other artists signed an open letter to the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, Jeremy Hunt, protesting against cutbacks in the arts.[120]

In popular culture

In 1966, while working on a series of etchings based on love poems by the Greek poet Constantine P. Cavafy, Hockney starred in a documentary by filmmaker James Scott, entitled Love's Presentation.[122] He was the subject of Jack Hazan's 1974 biopic, A Bigger Splash, named after Hockney's 1967 pool painting of the same name. Hockney was also the inspiration of artist Billy Pappas in the documentary film Waiting for Hockney (2008), which debuted at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2008.[123]

Hockney was inducted into Vanity Fair's International Best-Dressed Hall of Fame in 1986.[124] In 2005 Burberry creative director Christopher Bailey centred his entire spring/summer menswear collection around the artist and in 2012 fashion designer Vivienne Westwood, a close friend, named a checked jacket after Hockney.[125] In 2011 British GQ named him one of the 50 Most Stylish Men in Britain and in March 2013 he was listed as one of the Fifty Best-dressed Over-50s by The Guardian.[126]

Hockney was commissioned to design the cover and pages for the December 1985 issue of the French edition of Vogue. Consistent with his interest in cubism and admiration for Pablo Picasso, Hockney chose to paint Celia Birtwell (who appears in several of his works) from different views for the cover, as if the eye had scanned her face diagonally.

David Hockney: A Rake's Progress (2012) is a biography of Hockney covering the years 1937–1975, by writer/photographer Christopher Simon Sykes.[127]

In 2012, Hockney featured in BBC Radio 4's list of The New Elizabethans to mark the diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II. A panel of seven academics, journalists and historians named Hockney among the group of people in the UK "whose actions during the reign of Elizabeth II have had a significant impact on lives in these islands and given the age its character".[128]

The 2015 Luca Guadagnino's film A Bigger Splash was named after Hockney's painting.[129]

In Peter Hyams' 1990 movie thriller Narrow Margin the villain tells a man who stole money from him, "If you have to sell your David Hockneys [to pay me back], then you will do that."

David Hockney Foundation

The David Hockney Foundation—both the U.K. registered charity 1127262 and the U.S.A. 501(c)(3) private operating foundation—was created by the artist in 2008. In 2012, Hockney, worth an estimated $55.2 million (approx. £36.1 m), transferred paintings valued at $124.2 million (approx. £81.5 m) to the David Hockney Foundation, and gave an additional $1.2 million (approx. £0.79 m) in cash to help fund the foundation's operations.[130]

The Foundation's mission is to advance appreciation and understanding of visual art and culture through the exhibition, preservation, and publication of David Hockney's work. Richard Benefield, who organized David Hockney: A Bigger Exhibition in 2013–2014 at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, became the first executive director in January 2017.[131]

The Foundation owns over 8,000 works comprising paintings, drawings, watercolors, complete editioned prints, stage design, multi-camera movies, and other media. They also hold 203 sketchbooks and Hockney's personal photo albums from 1961 to 1990. The Foundation manages various loans to museums and exhibitions around the world, including Happy Birthday, Mr. Hockney! at the Getty celebrating his 80th birthday, and the retrospective exhibitions of 2017–2018 at the Metropolitan Museum, Centre Georges Pompidou, and Tate Britain.

Books by Hockney

- 72 Drawings (1971), Jonathan Cape, London, ISBN 0-224-00655-X

- David Hockney (1976), Thames & Hudson, London, ISBN 0-500-09108-0

- Blue Guitar: Etchings by David Hockney Who Was Inspired by Wallace Stevens Who Was Inspired by Pablo Picasso (1977), Petersburg Press, New York, ISBN 0-902825-03-8

- Travels with Pen, Pencil and Ink (1978), Petersburg Press, New York, ISBN 0-902825-07-0

- Pictures by David Hockney (ed. Nikos Stangos) (1979), Thames & Hudson, London, ISBN 0-500-27163-1

- Travels with Pen, Pencil and Ink (1980), Tate Gallery, London ISBN 0-905005-58-9

- Looking at Pictures in a Book at the National Gallery (The artist's eye) (1981), London: National Gallery

- Photographs (1982), Petersburg Press, New York, ISBN 0-902825-15-1

- Hockney's Photographs (1983), Arts Council of Great Britain, London, ISBN 0-7287-0382-3

- Martha's Vineyard and other places: My Third Sketchbook from the Summer of 1982 (with Nikos Stangos), (1985), Thames and Hudson, London, ISBN 0-500-23446-9

- David Hockney: Faces 1966–1984 (1987), Thames & Hudson, London, ISBN 0-500-27464-9

- That's the Way I See It (with Nikos Stangos) (1989), Thames & Hudson, London, ISBN 0-500-28085-1

- Hockney's Alphabet (with Stephen Spender) (1991) Random House, London, ISBN 0-679-41066-X

- David Hockney: Some Very New Paintings (Intro by William Hardie) (1993), William Hardie Gallery, Glasgow, ISBN 1-872878-03-2

- Off the Wall: A Collection of David Hockney's Posters 1987–94 (with Brian Baggott) (1994), Pavilion Books, ISBN 1-85793-421-0

- David Hockney: Poster Art (1995), Chronicle Books, ISBN 0-8118-0915-3

- Picasso (1999), Galerie Lelong ISBN 2-86882-026-3

- Une éducation artistique (1999), Galerie Lelong ISBN 2-86882-028-X

- Hockney's Pictures (2001), Thames & Hudson, London, ISBN 0-500-28671-X

- Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the lost techniques of the Old Masters (Thames & Hudson; Viking Studio, 2001; Expanded Edition 2006)

- Hockney on Art: Conversations with Paul Joyce (2008), Little, Brown and Company, New York, ISBN 1-4087-0157-X

- David Hockney's Dog Days (2011), Thames & Hudson, London, ISBN 0-500-28627-2

- A Yorkshire Sketchbook (2011), Royal Academy of Arts, London, ISBN 1-907533-23-0

- David Hockney: A Bigger Picture (2012), Thames & Hudson, London, ISBN 978-0-500-09366-5

- David Hockney: A Bigger Exhibition (2013), Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and DelMonico with Prestel, ISBN 978-3-7913-5334-0

- A History of Pictures (with Martin Gayford) (2016), Thames & Hudson, London, ISBN 978-0-500-23949-0

- In October 2016, Taschen published a new book, David Hockney: A Bigger Book, costing £1,750 (£3,500 with an added loose print). The artist curated the selection of more than 60 years of his work reproduced within 498 pages. The book, weighing 78 lbs, had gone through 19 proof stages.[90] He unveiled the book at the Frankfurt Book Fair where he was the keynote speaker at the opening press conference.[132] ISBN 978-3-8365-0787-5

See also

References

- "Commencement speakers and / or honorary degrees" (PDF). Otis College of Art and Design. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- J. Paul Getty Museum. David Hockney. Archived 13 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- "David Hockney A Bigger Picture". Royal Academy of Arts. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- David Hockney, Mulholland Drive (1980) LACMA. Retrieved 1 May 2013

- Kino, Carol (15 October 2009). "David Hockney's Long Road Home". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- Vogel, Carol (11 October 2012). "Hockney's Wide Vistas". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Gabriel, Trip (1993). "At Home with/David Hockney: Acquainted with Light". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "David Hockney painting smashes record for living artist as artwork fetches $90 million at auction". The Telegraph. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- "David Hockney painting poised to smash auction records". CNN. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- "Perspective | How record-setting art auctions are ruining the old neighborhood". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "David Hockney's Famed Pool Scene Sells for $90.3 M. at Christie's, New Record for Work by Living Artist at Auction". Art News. 16 November 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- Holland, Oscar (16 May 2019). "Jeff Koons' $91M 'Rabbit' sculpture sets new auction record". CNN. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- Gayford, Martin (2016). A Bigger Message: Conversations with David Hockney. p. 236. ISBN 9780500238875.

- Sykes, Christopher Simon (2011). Hockney: The Biography, Volume 1. London: Century. p. 13. ISBN 9781846057090.

- "The Royal Hall Harrogate 1 – Series 38". Antiques Roadshow. Series 38. Episode 1. 27 March 2016. BBC. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- "John Loker". Bradford College. 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "David Oxtoby". Redfern Gallery. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- Rosenberg, Karen (20 November 2019). "Overlooked No More: Pauline Boty, Rebellious Pop Artist". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Ward, Ossian. "David Hockney interview". Time Out. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "When David met Gregory: The man behind Hockney's career". Barnebys. 3 July 2017. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- Weinraub, Bernard (15 August 2001). "Enticed by Bright Light; From David Hockney, a Show of Photocollages in Los Angeles". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- "Artist David Hockney sells the 1,908-square-foot house in Los Angeles' Hollywood Hills to his former lover and now working partner and friend Gregory Evans for $600K". BergProperties.com. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "In Conversation: David Hockney with William Corwin". The Brooklyn Rail. 1 February 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- White, Edmund (8 September 2006). "Sunlight, beaches, and boys". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Nicholas Wilder, 51, Artist and Art Dealer The New York Times, 16 May 1989.

- White, Edmund (8 September 2006). "Sunlight, beaches and boys". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- "The David Hockney Foundation: Self Portraits". Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Weschler, Lawrence (24 January 2000). "The Looking Glass". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Andrew Marr (6 October 2001). "What the eye didn't see..." The Guardian. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Cumming, Laura (3 July 2016). "David Hockney RA: 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life review – are you sitting colourfully?". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Beaumont-Jones, Julia. "The Rake's Progress," Art in Print, Vol. 4 No. 4 (November–December 2014).

- David Hockney, A Hollywood Collection (S.A.C. 41–46; Tokyo 41–46) (1965) Christie's, Hockney on Paper, 17 February 2012, London.

- Tate. "'A Rake's Progress', David Hockney, 1961–3 | Tate". Tate Etc. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "The David Hockney Foundation: Illustrations for Fourteen Poems from C.P. Cavafy". Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "The David Hockney Foundation: Illustrations for Six Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm". Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Hockney, Davis (1976–1977). "The Old Guitarist' From The Blue Guitar". British Council; Visual Arts. Petersburg Press. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- Hockney, David; Stevens, Wallace (1 January 1977). The Blue Guitar: Etchings By David Hockney Who Was Inspired By Wallace Stevens Who Was Inspired By Pablo Picasso. Petersburg Ltd. ISBN 978-0-902825-03-1.

- "David Hockney| Sunflower| Paper Pools series| ARCHEUS / POST-MODERN". www.archeus.com. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "The David Hockney Foundation: Home Made Prints". Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "The David Hockney Foundation: Moving Focus". Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Hockney on Photography: Conversations with Paul Joyce (1988) ISBN 0-224-02484-1

- Walker, John. (1992) "Joiners". Glossary of Art, Architecture & Design since 1945, 3rd. ed.

- "Image of Pearblossom Highway". Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- "Image of Kasmin 1982". Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- "Image of photocollage My Mother, Bolton Abbey, 1982". Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Hockney on Art – Paul Joyce ISBN 1-4087-0157-X

- Lawrence Weschler,"David Hockney's iPhone Passion", The New York Review of Books, 22 October 2009

- Gayford, Martin. "David Hockney's IPad Doodles Resemble High-Tech Stained Glass" Bloomberg, 26 April 2010.

- Jackie Wullschlager (13 January 2012), "Blue-sky painting" Financial Times.

- “Westminster Abbey Queen's Window by David Hockney revealed“. BBC News. Retrieved 15 November 2018

- Gayford, Martin. "The Mind's Eye". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "David Hockney Plays with Perspective in an L.A. Exhibition | Architectural Digest". Architectural Digest. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Hockney, David (2018). David Hockney : something new in painting (and photography) [and even printing]. Weschler, Lawrence,, Pace Gallery. New York. ISBN 9781948701037. OCLC 1030918605.

- Isenberg, Barbara (6 December 2009). "The worlds of David Hockney". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- Thompson, Jessie (7 February 2017). "David Hockney at Tate Britain: Five Hockney paintings to bring you joy". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Chu, Henry (12 February 2012). "David Hockney brings color back home". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- David Hockney: Paintings 2006–2009, 29 October – 24 December 2009 Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine Pace Gallery, New York.

- "Bigger Trees near Warter as seen in the Royal Academy, June 2007". Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- Higgins, Charlotte (8 April 2008). "Hockney's big gift to the Tate: a 40ft landscape of Yorkshire's winter trees". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- Simon Crerar "David Hockney donates Bigger Trees Near Warter to Tate", The Times, 7 April 2008.

- Wollheim, Bruno. "A Bigger Picture". Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- The Editors of ARTnews (22 December 2017). "From the Archives: John Russell on Works by David Hockney for a Production of 'Ubu Roi,' in 1966". ARTnews. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Rockwell, John (10 January 1991). "David Hockney Is Back in Opera, With a Few Ifs, Ands and Buts". The New York Times.

- Russell, John (20 February 1981). "David Hockney's Designs For Met Opera's 'Parade'". The New York Times.

- Jr., Theodore W. Libbey. "Dexter and Hockney Team for Stravinsky Triple Bill". Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Times, John Russell and Special To the New York. "Art: Hockney's Design for 'Tristan und Isolde' in Los Angeles". Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "San Francisco Opera Presents Opera Medal to David Hockney". sfopera.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "The David Hockney Foundation: The Foundation". Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "Pace Gallery - David Hockney - Documents". Pace Gallery. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- David Hockney Pace Gallery, New York.

- "Royal Academy". Archived from the original on 19 April 2012.

- Nairn, Olivia (29 February 2012). "David Hockney RA: A Bigger Picture". Creatures of Culture. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Stuff-Review, "Why we love tech: David Hockney's 'A Bigger Picture' is contemporary art done on an iPad"

- "David Hockney with William Corwin". The Brooklyn Rail. February 2012.

- "Hockney topples Hirst as Tate's most popular living artist". theartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "David Hockney. A Bigger Picture". Museum Ludiwg. 2013. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- "MuseumZero: David Hockney- Big vs Small Screen". museumzero.blogspot.com.

- Tate. "HOCKNEY IS TATE BRITAIN'S MOST VISITED EXHIBITION EVER – Press Release | Tate". Tate Etc. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "David Hockney at the Tate Britain". 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- "Iconic Works by David Hockney to Celebrate His 80th Birthday | artnet News". artnet News. 9 July 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- "ArtPremium – David Hockney: The Versatile Hand". ArtPremium. 3 October 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "Ranked: the top ten most popular shows in their categories from around the world". theartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Budick, Ariella (13 April 2018). "David Hockney: the master illusionist". Financial Times. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "Pace Gallery's upcoming David Hockney exhibition includes 18 new artworks". It’s Nice That. 21 March 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Searle, Adrian (18 October 2019). "Copulation at its fruitiest – David Hockney, Alan Davie, Christina Quarles review". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Reynolds, Emma (27 March 2009). "Your chance to own an 'exceptional' Hockney". Islington Tribune. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- Solomon, Deborah (17 August 2012). "California Dreams". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- "Artist David Hockney's assistant dies". Reuters via ABC News Online. 19 March 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- "Dominic Elliott died from drinking acid". BBC News. 29 August 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- Lynn Barber (2016), "When I'm painting I feel 30. It's only when I stop that I know I'm not", Sunday Times Magazine, 11 September 2016, pp.10–15

- "Hockney due to sell his home in Bridlington". Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Ward, Audrey (11 September 2016). "Off the market: Hockney's former Yorkshire home". The Sunday Times. ISSN 0956-1382. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Sonnenstrahl, Deborah M. (2002). Deaf Artists in America, Colonial to Contemporary. San Diego: Dawnsign. pp. 241–248.

- "Ten ½ things you didn't know about David Hockney". Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- Cytowic, Richard E. (2002). Synesthesia: A Union of the Senses. ISBN 9780262032964.

- "Homage to Michelangelo, (Color etching, soft ground etching and aquatint)". Curators at Work III. Muscarelle Museum of Art. 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- "David Hockney appointed to Order of Merit". BBC Magazine. BBC News. 1 January 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- Appointments to the Order of Merit, 1 January 2012– the official website of The British Monarchy Archived 7 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Progress Medal – The Royal Photographic Society". Rps.org. Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Royal Photographic Society's Centenary Award Archived 1 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine/ Retrieved 13 August 2012

- "Centenary Medal – The Royal Photographic Society". Rps.org. Archived from the original on 1 December 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "The Cultural Award of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Photographie (DGPh)". Deutsche Gesellschaft für Photographie e.V.. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- "David Hockney RA – Painters – Royal Academicians – Royal Academy of Arts". royalacademy.org.uk. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- David Hockney: Paintings 2006–2009, 2 October – 24 December 2009 Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine Pace Gallery, New York.

- Dalya Alberge (23 November 2011), Hockney named Britain's most influential artist The Independent.

- "New faces on Sgt Pepper album cover for artist Peter Blake's 80th birthday". The Guardian. 10 November 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- "Sir Peter Blake's new Beatles' Sgt Pepper's album cover". BBC. 9 November 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- "David Hockney 1990-1999". 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 2 June 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "Entertainment – Hockney painting sells for £2.6m". BBC News. 22 June 2006. Retrieved 22 June 2006.

- "David Hockney - The Splash". sothebys.com. 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "Hockney's The Splash fetches £23.1m at auction". BBC News. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- "David Hockney's Woldgate Woods sells for £9.4m at auction". BBC News. 18 November 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- "Hockney record broken twice in a night". BBC News. 17 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "David Hockney Painting Sells for $90 Million, Smashing Record for Living Artist". The New York Times. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- "Search". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. 24 October 2011.

- "Standpoint Advisory Board". Standpoint. 2009. Archived from the original on 1 June 2008.

- "David Hockney – Exclusive sketches for his new Tate masterpiece". Standpoint. 2008. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- BBC press office (2009). "Radio 4's Today announces this year's guest editors". BBC.

- Peter Walker, "Turner prize winners lead protest against arts cutbacks," The Guardian, 1 October 2010.

- "David Hockney". Front Row. 7 September 2011. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- "Love's Presentation (1966)". BFI. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- IMDB, "Waiting for Hockney (2008)"

- Fair, Vanity. "The International Best-Dressed Hall of Fame 2015". Vanities. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Ellie Pithers (25 January 2012), David Hockney: back on the fashion map The Daily Telegraph

- Cartner-Morley, Jess; Mirren, Helen; Huffington, Arianna; Amos, Valerie (28 March 2013). "The 50 best-dressed over 50s". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- Simon, Christopher (17 April 2012). "David Hockney: A Rake's Progress". New York Journal of Books. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Naughtie, James. "David Hockney". The New Elizabethans. BBC Radio Four.

- "Luca Guadagnino, Tilda Swinton & Dakota Johnson". Vogue Italia. 1 September 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- Boehm, Mike (1 May 2012). "David Hockney art gifts win him top rank in British philanthropy". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "S.F. museum veteran Richard Benefield to lead David Hockney Foundation". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "David Hockney Unveils "A Bigger Book," a Massive 500-page Visual Autobiography". Swankism. 25 October 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

Further reading

- Weschler, L. Cameraworks (with David Hockney – photographer) (1984) Alfred A. Knopf, (portions of the essay by Weschler appeared in the New Yorker in a slightly different form), ISBN 0-394-53733-5

- Geldzahler, H., Knight, C., Kitaj, R. B., Schiff, G., Hoy, A., Silver, K. E. and Weschler, L. David Hockney: A Retrospective (Painters & sculptors) (1988), Thames and Hudson, London, ISBN 0-500-23514-7

- Shanes, E. Hockney Posters (with David Hockney), (1988), Crown Publishing Group, ISBN 0-517-56584-6

- Luckhardt, U. and Melia, P. David Hockney: A Drawing Retrospective (1995), Thames and Hudson, London, ISBN 0-500-09255-9

- Livingstone, M. David Hockney: Space and Line (1999), Annely Juda Fine Art, London, ISBN 1-870280-74-1

- Livingstone, M. David Hockney: Painting on Paper (2002), Annely Juda Fine Art, London, ISBN 1-870280-95-4

- Livingstone, M. David Hockney: Egyptian Journeys (2002), American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, ISBN 977-424-737-X

- Frémon, J David Hockney, Close and far (2001) ISBN 978-2868820532

- Howgate, S. David Hockney Portraits (2006), National Portrait Gallery, ISBN 1-85514-362-3

- Melia, P. and Luckhardt, U. David Hockney: Paintings (2007), Prestel, Munich, ISBN 3-7913-3718-1

- Becker, C. and Livingstone, M. David Hockney (2009), Swiridoff Verlag, Künzelsau, ISBN 3-89929-154-9

- Sykes, C. S. Hockney: The Biography (2011), Century, ISBN 1-84605-708-6

- Seckiner, S. South (Güney), published July 2013, consists of 12 article and essays. One of them, American Collectors, re-focus on David Hockney's importance in the philosophy of art. ISBN 978-605-4579-45-7.

- Dagen, P. David Hockney, The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate (2015) ISBN 9782868821188

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to David Hockney. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: David Hockney |