Victor Horta

Victor Pierre Horta (French: [ɔʁta]; Victor, Baron Horta after 1932; 6 January 1861 – 8 September 1947) was a Belgian architect and designer, and one of the founders of the Art Nouveau movement.[1] His Hôtel Tassel in Brussels built in 1892–1893, is often considered the first Art Nouveau house, and, along with three of his other early houses, is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The curving stylized vegetal forms that Horta used influenced many others, including architect Hector Guimard, who used it in the first house he designed in Paris and in the entrances he designed for the Paris Metro.[2][3] He is also considered a precursor of modern architecture for his open floor plans and his innovative use of iron, steel and glass.[4]

Victor Horta | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Born | 6 January 1861 |

| Died | 8 September 1947 (aged 86) Brussels, Province of Brabant, Belgium |

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards |

|

| Buildings |

|

| Projects | Brussels-Central railway station |

| Signature | |

His later work moved away from Art Nouveau, and became more geometric and formal, with classical touches, such as columns. He made a highly original use of steel frames and skylights to bring light into the structures, open floor plans, and finely-designed decorative details. His later major works included the Maison du Peuple/Volkshuis in Brussels, (1895–1899); the Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels (1923–1929); and Brussels Central Station (1913–1952).

In 1932, King Albert I of Belgium conferred on Horta the title of Baron for his services to the field of architecture. Four of the buildings he designed have been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Life and early work

Victor Horta was born in Ghent, Belgium, on 6 January 1861. His father was a master shoemaker, who, as Horta recalled, considered craftsmanship a high form of art. The young Horta began by studying music at the Ghent Conservatory. He was expelled for misbehaviour and went instead to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent. At the Ghent Conservatory an aula is named after him now.[5] When he was seventeen he moved to Paris and found work with architect and designer Jules Debuysson.

Horta's father died in 1880, and Horta returned to Belgium. He moved to Brussels and married his first wife, with whom he later fathered two daughters. He began to study architecture at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts. He became friends with Paul Hankar, another early pioneer of Art Nouveau architecture. Horta did well in his studies and was taken on as an assistant by his professor Alphonse Balat, architect to Leopold II of Belgium. Horta worked with Balet on the construction of the Greenhouses of Laeken, Horta's first work to utilise glass and iron.[5] In 1884, Horta won the first Prix Godecharle to be awarded for Architecture for a proposed new building for the Belgian Parliament. On his graduation from the Royal Academy, he was awarded the Grand Prize in architecture.[5]

In the years that followed joined the Central Society of Belgian Architecture, and designed and completed three houses in a traditional style and took part in several competitions. In 1892, he was named head of the department of graphic design for Architecture at the Free University of Brussels, and promoted to Professor in 1893.[5][6]

At this time, through lectures and exhibitions organised by the artists' association Les Vingt, Horta became familiar with the British Arts and Crafts Movement , and the developments in book design, and especially textiles and wallpaper, which influenced his own later work.[7]

In 1893, he built a town house, the Autrique House for his friend Eugène Autrique. The interior had a traditional floor plan, due to a limited budget, but the facade previewed some of the elements he developed into the full Art Nouveau style, including iron columns, and ceramic floral designs.[8]

In 1894, Horta was elected President of the Central Society of Belgian Architecture, although he resigned the following year following a dispute caused when he was awarded the commission for a kindergarten on Rue Saint-Ghislain/Sint-Gissleinsstraatt without a public competition.[5]

The Town Houses and the beginning of Art Nouveau

Hôtel Tassel (1892–1893)

The major breakthrough for Horta came in 1892, when he was commissioned to design a home for the Belgian Professor and scientist Emile Tassel. The Hôtel Tassel was completed in 1893. The stone facade, designed to harmonize with the neighboring buildings, was fairly traditional, but the interior was strikingly new. Horta used the technologies of glass and iron, which he had practiced on the royal greenhouses at Laeken, to create an interior filled with light and space. The house was built around an open central stairway. The decoration of the interior featured curling lines, modeled after vines and flowers, which were repeated in the ironwork railings of the stairway, in the tiles of the floor, in the glass of the doors and skylights, and painted on the walls. The building is widely recognized as the first appearance of Art Nouveau in architecture.[9][10] In 2000, it was designated, along with three other townhouses designed soon afterwards, as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In designating these cites, UNESCO explained: "The stylistic revolution represented by these works is characterised by their open plan, the diffusion of light, and the brilliant joining of the curved lines of decoration with the structure of the building."[11]

- Facade of the Hôtel Tassel, Brussels (1893)

- Stairway of the Hôtel Tassel

- Floor of the Hôtel Tassel, with the characteristic curling vegetal design

Hôtel Solvay (1898–1900)

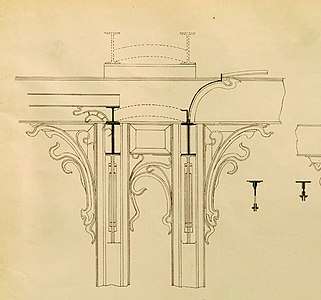

The Hôtel Solvay, on Avenue Louise/Louizalaan in Brussels, was constructed for Armand Solvay, the son of the Belgian chemist and industrialist Ernest Solvay. Horta had a virtually unlimited budget, and used the most exotic materials in unusual combinations, such as marble, bronze and rare tropical woods in the stairway decoration. The stairway walls were decorated by the Belgian pointillist painter Théo van Rysselberghe. Horta designed every detail including the bronze doorbell and the house number, to match the overall style:[12]

Entrance of the Hôtel Solvay, Brussels (1898–1900)

Entrance of the Hôtel Solvay, Brussels (1898–1900).jpg) Facade of the Hôtel Solvay

Facade of the Hôtel Solvay Design of Hôtel Solvay interior decoration by Horta

Design of Hôtel Solvay interior decoration by Horta.jpg) Doorbell of the Hôtel Solvay

Doorbell of the Hôtel Solvay

Hôtel Van Eetvelde (1898–1900)

The Hôtel van Eetvelde is considered one of Horta's most accomplished and innovative buildings, because of highly original Winter Garden interior and the imaginative details throughout. The open floor plan of the Hôtel Van Eetvelde was particularly original, and offered an abundance of light, both horizontally and vertically, and a great sensation of space. A central court went up the height of the building, bringing light from the skylight above. On the main floor, the oval-shaped salons were open to the courtyard, and also received light from large bay windows. It was possible to look from one side of the building to other from any of the salons on the main floor.[13]

Facade of the Hôtel van Eetvelde, Brussels (1898–1900)

Facade of the Hôtel van Eetvelde, Brussels (1898–1900) Detail of the Winter Garden of the Hôtel van Eetvelde

Detail of the Winter Garden of the Hôtel van Eetvelde.jpg) The Winter Garden of the Hôtel van Eetvelde

The Winter Garden of the Hôtel van Eetvelde Doorway with stained glass

Doorway with stained glass Detail of the facade of the Hôtel van Eetvelde

Detail of the facade of the Hôtel van Eetvelde

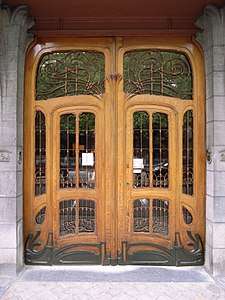

Horta House and Studio (1898–1901)

The Horta House and Studio, now the Horta Museum, was Horta's residence and office, and was certainly more modest than the other houses, but it had its own original features and equally fine craftsmanship and mastery of details. He made unusual combinations of materials, such as wood, iron and marble in the staircase decoration.[14]

The novel element in Horta's houses and then his larger buildings was his search for maximum transparency and light, something often difficult to achieve with the narrow building sites in Brussels. He achieved this by use of large windows, skylights, mirrors, and especially by his open floor plans, which brought in light from all sides and from above.[15]

Detail of the door of the Horta Museum, Brussels (1898–1901)

Detail of the door of the Horta Museum, Brussels (1898–1901) The Horta Museum, composed of Horta's residence and workshop side-by-side

The Horta Museum, composed of Horta's residence and workshop side-by-side Stairway and skylight and stairway of the Horta Museum

Stairway and skylight and stairway of the Horta Museum- Balcony of the Horta Museum

Hôtel Aubecq (1899–1902)

The Hôtel Aubecq in Brussels was one of his late houses, made for the industrialist Octave Aubecq. As with his other houses, it featured a skylight over the central staircase, filling the house with light. Its peculiarity was the octagonal shape of the rooms, and the three facades with windows, designed to give maximum light. The owner originally wished to keep his original family furniture, but because of the odd shape of the rooms, Horta was commissioned to create new furniture.

By 1948, Art Nouveau was out of style, the house was sold to a new owner, who wished to demolish it. A movement began to preserve the house, but in the end only the facade and the furnishings were saved by the City of Brussels. The facade was disassembled and put into storage, and many proposals were made for its reconstruction, but none were carried out. Some of the furnishings are now on display at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.[16]

_in_the_H%C3%B4tel_Aubecq_(building_destroyed%2C_Brussels).jpg) Upper part of the hall in the Hôtel Aubecq, Brussels (1899–1902)

Upper part of the hall in the Hôtel Aubecq, Brussels (1899–1902)- Furnishings of the Hôtel Aubecq on display at the Musée d'Orsay, Paris

.jpg) Salon of the Hôtel Aubecq

Salon of the Hôtel Aubecq

Maison du Peuple (1895–1899)

While Horta was building luxurious town houses for the wealthy, he also applied his ideas to more functional buildings. From 1895 to 1899, he designed and built the Maison du Peuple/Volkshuis ("House of the People"), the headquarters for the Belgian Workers' Party. This was a large structure including offices, meeting rooms, a café and a conference and concert hall seating over 2,000 people. It was a purely functional building, constructed of steel columns with curtain walls. Unlike his houses, there was virtually no decoration. The only recognizable Art Nouveau feature was a slight curving of the steel pillars supporting the roof. As with his houses, the building was designed to make a maximum use of light, with large skylights over the main meeting room. It was demolished in 1965, despite an international petition of protest by over 700 architects. The materials of the building were saved for possible reconstruction, but were eventually scattered around Brussels. Some parts were used for the construction of the Brussels Metro system.[17]

_(destroyed%2C_Brussels)%2C_exterior_2.jpg) Facade of the Maison du Peuple, Brussels (1895–1899)

Facade of the Maison du Peuple, Brussels (1895–1899)_(destroyed%2C_Brussels)%2C_theatre_hall.jpg) Theatre and Meeting Hall of the Maison du Peuple

Theatre and Meeting Hall of the Maison du Peuple_(destroyed%2C_Brussels)%2C_dining_hall.jpg) Restaurant of the Maison du Peuple

Restaurant of the Maison du Peuple

Beginning in about 1900, Horta's buildings gradually became more simplified in form, but always made with great attention to functionality and to craftsmanship. Beginning in 1903, he constructed the Grand Bazar Anspach, a large department store, with his characteristic use of large windows, open floors, and wrought iron decoration.

In 1907, a Horta designed the Museum for Fine Arts in Tournai, although it did not open until 1928 due to the war.

Magasins Waucquez (1905)

The Magasins Waucquez (now the Belgian Comic Strip Center) was originally a department store specializing in textiles. In its design, Horta used all his skill with steel and glass to create dramatic open spaces and to give them an abundance of light from above. The steel and glass skylight is combined with decorative touches, such as neoclassical columns. The store closed in 1970, and, because of its connection to Horta, was declared a protected historical site. Now a museum of a particular Belgian speciality, the comic strip, it also has a room devoted to Horta.

Facade of the former Magasins Waucquez, now the Belgian Comic Strip Center, Brussels (1905)

Facade of the former Magasins Waucquez, now the Belgian Comic Strip Center, Brussels (1905) Entrance hall of the former Magasins Waucquez, now the Belgian Comic Strip Center

Entrance hall of the former Magasins Waucquez, now the Belgian Comic Strip Center Upper floor of the Belgian Comic Strip Center

Upper floor of the Belgian Comic Strip Center

Brugmann University Hospital (1906)

In 1906, Horta accepted the commission for the new Brugmann University Hospital (now the Victor Horta Site of the Brugmann University Hospital). Developed to take into account the views of the clinicians and hospital managers, Horta's design separated the functions of the hospital into a number of low-rise pavilions spread over the 18 hectares (44 acres) park based campus, and work began in 1911. Although used during World War I, the official opening was delayed until 1923. Its unusual design and layout attracted great interest from the European medical community, and his buildings continue in use to this day.[18]

The First World War – travel to the United States

In February 1915, as World War I was underway and Belgium was occupied, Horta moved to London[5][19] and attended the Town Planning Conference on the Reconstruction of Belgium, organised by the International Garden Cities and Town Planning Association.[20] Unable to return to Belgium, at the end of 1915, he traveled to the United States, where he gave a series of lectures at American universities, including Cornell, Harvard, MIT, Smith College, Wellesley College and Yale. In 1917, he was named Charles Eliot Norton Memorial Lecturer and Professor of Architecture at George Washington University.[5]

Later Projects – debut of modernism (1919–1939)

On Horta's return to Brussels in January 1919, he sold his home and workshop on Rue Américaine/Amerikaansestraat,[6] and also became a full member of the Belgian Royal Academy.[5]

The post-war austerity meant that Art Nouveau was no longer affordable or fashionable. From this point on Horta, who had gradually been simplifying his style over the previous decade, no longer used organic forms, and instead based his designs on the geometrical. He continued to use rational floor plans, and to apply the latest developments in building technology and building services engineering. The Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels, a multi-purpose cultural centre designed in a more geometric style similar to Art Deco.[5]

Centre for Fine Arts (1923–1929)

Horta developed the plans for the Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels beginning in 1919, with construction starting in 1923. It was completed in 1929. It was originally intended to be built of stone, but Horta made a new plan of reinforced concrete with a steel frame. He had intended the concrete to be left exposed in the interior, but the final appearance did not meet his expectations, and he had it covered. The concert hall itself is in an unusual ovoid, or egg shape, and is accompanied by art galleries, meeting rooms, and other functional rooms. The building is placed on a complex hillside site, and occupies eight levels, much of it underground. It also had to be designed to avoid blocking the view from the Royal Palace, on the hill just above it.[21]

In 1927, Horta became the Director of the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, a post he held for four years until 1931. In recognition of his work, Horta was awarded the title of Baron by Albert I of Belgium in 1932.[6]

Exhibition hall of the Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels (1923)

Exhibition hall of the Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels (1923).jpg) The Centre for Fine Arts shortly after its completion

The Centre for Fine Arts shortly after its completion Concert Hall at the Centre for Fine Arts

Concert Hall at the Centre for Fine Arts.jpg) Window of the Centre for Fine Arts

Window of the Centre for Fine Arts

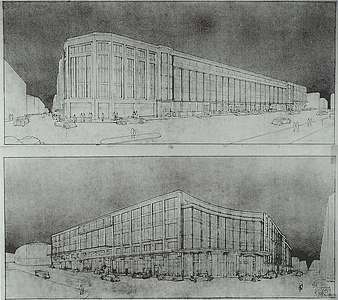

Brussels Central Station (1913–1952)

In 1910, Horta began working on drawings on his most ambitious and longest running project: Brussels-Central railway station. He was formally commissioned as the architect in 1913, but work did not actually begin until after World War II, in 1952.[5] It was originally planned that the station would just part of a much larger redevelopment project, which Horta had conceived in the 1920s, but this was never realized.[5]

The start of construction was seriously delayed due to the lengthy process of purchasing and demolishing over thousand buildings along the route of the new railway between the main Brussels stations, and then the First World War. Construction finally began in 1937 as part of the plans to boost the economy during the Great Depression, before being delayed again by the outbreak of World War II.[22] Horta was still working on the station when he died in 1947. The building the station was finally completed, to his plans, by his colleagues led by Maxime Brunfaut. It opened on 4 October 1952.[23][24]

Draft of Brussels-Central railway station by Victor Horta (1913–1952)

Draft of Brussels-Central railway station by Victor Horta (1913–1952) Main hall of Brussels-Central railway station

Main hall of Brussels-Central railway station Ceiling of Brussels-Central railway station

Ceiling of Brussels-Central railway station Stairway with exposed steel beams, Brussels-Central railway station

Stairway with exposed steel beams, Brussels-Central railway station

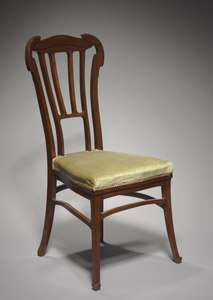

Furniture

Horta typically designed not only the building, but also the furniture, to match his particular style. His furniture became as well known as his houses; a displays of his furniture were shown at the 1900 Universal Exposition, in Paris, and the 1902 Turin Exposition of Modern Decorative Arts. It was typically hand-made, and the furniture for each house was different. In many cases the furniture lasted longer than the house. Its drawback was that, since it matched the house, it could not be changed to any other style, without disrupting the harmony of the room.

Dining room by Victor Horta displayed at the 1902 Turin International Exposition

Dining room by Victor Horta displayed at the 1902 Turin International Exposition Table designed by Horta for the 1902 Turin Exposition

Table designed by Horta for the 1902 Turin Exposition- Dining room furniture and wall panel from the Hôtel Aubecq (1902–1904)

Peacock Chair from either Hôtel Tassel or Castle of La Hulpe

Peacock Chair from either Hôtel Tassel or Castle of La Hulpe Mahogany chair (1900) (Cleveland Museum of Art)

Mahogany chair (1900) (Cleveland Museum of Art) Chair from the Hotel Aubecq (1902–04), now in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Chair from the Hotel Aubecq (1902–04), now in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Later work and personal life

In 1925, he was an architect of honor for the Belgian Pavilion at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, the exposition which gave its name to Art Deco.[25] In the same year, he became director of the section of fine arts of the Belgian Royal Academy of Fine Arts.

Horta and his first wife divorced in 1906. He married his second wife, Julia Carlsson, in 1908.[6]

In 1937, he completed the design of his final work, Brussels Central Station. In 1939, he began editing his memoirs.[25] Victor Horta died on 8 September 1947 and was interred in the Ixelles Cemetery in Brussels.

Heritage

After Art Nouveau lost favor, many of Horta's buildings were destroyed, most notably the Maison du Peuple/Volkshuis, demolished in 1965, as mentioned above. However, several of Horta's buildings are still standing in Brussels up to this day and some are available to tour. Most notable are the Magasins Waucquez, formerly a department store, now the Belgian Comic Strip Center and four of his private houses (hôtels), which were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site:

- Hôtel Tassel, designed and built for Prof. Émile Tassel in 1892–1893

- Hôtel Solvay, designed and built 1895–1900

- Hôtel van Eetvelde, designed and built 1895–1898

- Maison and Atelier Horta, designed in 1898, now the Horta Museum, dedicated to his work

Honours

- 1919

Coat of arms of the Baron Horta

Coat of arms of the Baron Horta- Officer of the Order of the Crown.[26]

- Member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium[27]

- 1920: Officer of the Order of Leopold[28]

- 1925: Director of the Classe of Beaux-Arts of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium[27]

- 1932: Created Baron Horta by Royal Decree and given a coat of arms

On 6 January 2015, Google Doodle commemorated his 154th birthday[29]

List of works

- 1885 : 3 houses, Twaalfkameren 49, 51, 53 in Ghent (design)

- 1889 : Temple of Human Passions, Cinquantenaire Park in Brussels (protected monument since 1976)

- 1890 : Maison Matyn, rue de Bordeauxstraat 50, 1060 Saint-Gilles

- 1890 : Renovations and interior decoration to the Brussels residence of Henri van Cutsem, Kunstlaan / Avenue des Arts 16, Saint-Josse-ten-Noode (Today Charlier Museum).

- 1892-1893 : Hôtel Tassel, rue Paul-Emile Jansonstraat 6 in Brussels

- 1893 : Maison Autrique, Haachtsesteenweg/Chaussée de Haecht 266 in Schaerbeek

- 1894 : Hôtel Winssinger, Munthofstraat / rue de l'Hôtel de la Monnaie 66 in Saint-Gilles

- 1894 : Hôtel Frison, rue Lebeaustraat 37 in Brussels

- 1894 : Atelier for Godefroid Devreese, Vleugelstraat / rue de l'aile 71 in Schaerbeek (modified)

- 1894 : Hôtel Solvay, Avenue Louise 224 in Brussels.

- 1895 : Interior decoration of the house of Anna Boch, Boulevard de la Toison d'Or / Guldenvlieslaan 78 in Saint-Gilles (demolished)

- 1895-1898 : Hôtel van Eetvelde, Avenue Palmerstonlaan 2/6 in Brussels

- 1896-1898 : Maison du Peuple / Volkshuis, place Vanderveldeplein in Brussels (demolished in 1965)

- 1897-1899 : Kindergarten, rue Sainte-Ghislaine / Sint-Gisleinstraat 40 in Brussels

- 1898-1900 : House and Studio of Victor Horta, rue Américaine / Amerikaansestraat 23–25 in Saint-Gilles (today the Horta Museum ).

- 1899 : Maison Frison "Les Épinglettes", avenue Circulaire / Ringlaan 70 in Uccle

- 1899 : Hôtel Aubecq, Avenue Louise 520 in Brussels (demolished in 1950)

- 1899-1903: Villa Carpentier (Les Platanes), Doorniksesteenweg 9–11 in Ronse

- 1900 : Extension of the Maison Furnémont, rue Gatti de Gamondstraat 149 in Uccle

- 1900 : Department store: A l'Innovation, rue Neuve 111 in Brussels (destroyed by fire in 1967)

- 1901 : House and Studio for the sculptor Fernant Dubois, Avenue Brugmannlaan 80 in Forest, Belgium

- 1901 : House and Studio for the sculptor Pieter-Jan Braecke, rue de l'Abdication / Troonafstandstraat 51 in Brussels

- 1902 : Hôtel Max Hallet, Avenue Louise 346 in Brussels.

- 1903 : Funeral monument for the composer Johannes Brahms on the "Zentralfriedhof" in Vienna (in collaboration with the Austrian sculptor Ilse Twardowski-Conrat)

- 1903 : Magasins Waucquez, rue du Sable / Zandstraat 20 in Brussels (since 1989 Belgian Centre for Comic Strip Art.

- 1903 : House for the art critic Sander Pierron, rue de l'Acqueduc / Waterleidingsstraat 157 in Ixelles

- 1903 : Grand Bazar Anspach, Bisschopsstraat / rue de l'Evêque 66 in Brussels (demolished)

- 1903 : Maison Emile Vinck, rue de Washingtonstraat 85, Ixelles (converted in 1927 by architect A.Blomme).

- 1903 : Department store: A l'Innovation, Chausée d'Ixelles / Elsenesteenweg 63–65 in Ixelles (converted)

- 1904 : Gym for the boarding school "Les Peupliers" in Vilvoorde.

- 1905 : Villa Fernand Dubois, rue Maredretstraat, Sosoye.

- 1906 : Brugmann Hospital, Place A. Van Gehuchtenplein in Jette; (First design; opened in 1923)

- 1907 : Magasins Hicklet, Nieuwstraat / rue Neuve 20 in Brussels (converted)

- 1909 : Wolfers Jewellers Shop, rue d'Arenberg / Arenbergstraat 11–13 in Brussels.

- 1910 : House for dr. Terwagne, Van Rijkswijcklaan 62, Antwerp.

- 1911 : Magasins Absalon, rue Saint-Christophe / Sint-Kristoffelstraat 41 in Brussels

- 1911 : Maison Wiener, Sterrekundelaan / avenue de l'Astronomie in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode (demolished)

- 1912 : Brussels-Central railway station (first designs; completed by Maxime Brunfaut and inaugurated in 1952).

- 1920 : Centre for Fine Arts, rue Ravensteinstraat in Brussels (first design; opened in 1928).

- 1925 : Belgian pavilion at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris in 1925.

- 1928 : Musée des Beaux-Arts Tournai in Tournai.

Gallery

- Brahms' grave on the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna designed by Horta

Notes

- Oudin, Bernard, Dictionnaire des Architectes, pg. 237

- Fahr-Becker, Gabriele, L'Art Nouveau, pg. 398

- Bridge, Adrian (3 October 2011). "Brussels: revisiting the magic of Victor Horta". The Telegraph. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- Oudin, Bernard, Dictionnaire des Architectes (1994), pg. 237

- Horta: Art Nouveau to Modernism, Harry N Abrams, ISBN 0-8109-6333-7

- Victor Horta – Biographie, Horta Museum, in French or Victor Horta – Biographie in Dutch

- Fahr-Becker 2015, p. 137.

- "La Maison Autrique, Bruxelles (Belgium)". Europa Nostra. 2005. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- Sembach, L'Art Nouveau- L'Utopie de la Réconciliation (2013) pg. 47

- Space Time and Architecture, Sigfreid Giedion, 1941

- UNESCO Word Heritage List entry

- Sembach (2013) p. 60

- Sembach 2013, p. 62.

- Fahr-Becker 2015, p. 143.

- Sembach 2013, p. 48.

- Pas de "faux" hôtel Aubecq, Guy Duplat, La Libre Belgique (in French), 1 July 2011

- Art Nouveau Architecture Picture Tour: Maison du Peuple

- CHU Brugmann, Notre histoire (in French)

- "Art Nouveau et plus particulièrement Victor Horta". Archived from the original on 7 May 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- The garden city education of Belgian planners around the First World War, Pieter Uyttenhove, Planning Perspectives, Volume 5, Issue 3 September 1990, pp. 271–283

- Wonderful Concert Halls in Europe Echo, Neils Le Large

- La jonction Nord-Midi

- belrail.be, Bruxelles-Central

- La rénovation de la gare de Bruxelles-Central – Passion-Trains

- "Biography of Horta on site of Horta Museum".

- Royal Decree of H.M. King Albert I on 14.11.1919

- http://www.academieroyale.be/fr/details-690/relations/victor-pierre-horta/secorig593/

- Royal Decree of H.M. King Albert I on 22.02.1920

- "Victor Horta's 154th Birthday". 6 January 2015.

References

- Aubry, Françoise; Vandenbreeden, Jos (1996). Horta — Art Nouveau to Modernism. Ghent: Ludion Press. ISBN 0-8109-6333-7.

- Cuito, Aurora (2003). Victor Horta. New York: Te Neues Publishing Company. ISBN 3-8238-5542-5.

- Dernie, David (1995). Victor Horta. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 1-85490-418-3.

- Fahr-Becker, Gabriele (2015). L'Art Nouveau (in French). H.F. Ullmann. ISBN 978-3-8480-0857-5.

- Oudin, Bernard (1994), Dictionnaire des Architects (in French), Paris: Seghers, ISBN 2-232-10398-6

- Sembach, Klaus-Jürgen (2013). L'Art Nouveau- L'Utopie de la Réconciliation (in French). Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-3005-5.

- Bogaert C., Lanclus K. & Verbeeck M. met medewerking van Linters A. 1979: Inventaris van het cultuurbezit in België, Architectuur, Stad Gent, Bouwen door de eeuwen heen in Vlaanderen 4NB Z-W, Brussel – Gent

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Victor Horta. |