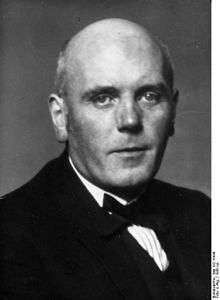

Paul Troost

Paul Ludwig Troost (17 August 1878 – 21 January 1934),[1][2] was a German architect. A favourite master builder of Adolf Hitler from 1930, his Neoclassical designs for the Führerbau and the Haus der Kunst in Munich influenced the style of Nazi architecture.

Life

Early career

Born in Elberfeld, Troost attended the Technical College of Darmstadt and, upon finishing his course, worked with Martin Dülfer in Munich. In about 1904, he opened his own architectural office and became a member of the modernist Deutscher Werkbund association. Troost designed several rooms of Cecilienhof Palace in Potsdam; he graduated from designing steamship décor for the Norddeutscher Lloyd shipping company before World War I, and the fittings for showy transatlantic liners like the SS Europa, to a style that combined Spartan traditionalism with elements of modernity.

An extremely tall, spare-looking, reserved Westphalian with a close-shaven head, Troost belonged to a school of architects like Peter Behrens and Walter Gropius who, even before 1914, reacted sharply against the highly ornamental Jugendstil movement and advocated a restrained, lean architectural approach, almost devoid of ornament.

Hitler

Troost and Hitler first met in 1930, through the agency of the Nazi publisher Hugo Bruckmann and his wife Elsa. Although, before 1933 he did not belong to the leading group of German architects, Troost became Hitler's foremost architect whose neo-classical style became for a time the official architecture of the Third Reich. His work filled Hitler with enthusiasm, and he planned and built state and municipal edifices throughout Germany.

In the autumn of 1933, he was commissioned to rebuild and refurnish Hitler's dwellings in the Reich Chancellery in Berlin.[3] Along with other architects like Ludwig Ruff, Troost planned and built State and municipal edifices throughout the country, including new administrative offices, social buildings for workers and bridges across the main highways. One of the many structures he planned before his death was the Haus der Kunst (House of German Art) in Munich,[4] modeled on Schinkel's Altes Museum in Berlin and intended to be a great temple for a "true, eternal art of the German people". It was a good example of the imitation of classical forms in monumental public buildings during the Third Reich, though subsequently Hitler moved away from the more restrained style of Troost, reverting to the more elaborate imperial grandeur that he had admired in the 19th century Vienna Ring Road (Ringstraße) boulevard of his youth.

Hitler's relationship to Troost was that of a pupil to an admired teacher. According to Albert Speer, who later became Hitler's favorite architect, the Führer would impatiently greet Troost with the words: "I can't wait, Herr Professor. Is there anything new? Let's see it!" Troost would then lay out his latest plans and sketches. Hitler frequently declared, according to Speer, that "he first learned what architecture was from Troost"'. The architect's death on 21 January 1934, after a severe illness, was a painful blow, but Hitler remained close to his widow Gerdy Troost, whose architectural taste frequently coincided with his own, which made her (in Speer's words) "a kind of arbiter of art in Munich." He was buried in the Munich Nordfriedhof (Northern Cemetery). The gravestone still survives although the family name has been removed.

Hitler posthumously awarded Troost the German National Prize for Art and Science in 1937.

See also

References

- Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich (Simon and Schuster, 1970) p49

- Sven Felix Kellerhoff, The Führer Bunker: Hitler's Last Refuge (Berlin Story Verlag, 2004) p38

- Seligmann, Matthew; Davison, John; and McDonald, John (2003). Daily Life in Hitler's Germany, p. 96. London: The Brown Reference Group plc. ISBN 0-312-32811-7.

- Zalampas, Sherree Owens (1990). Adolf Hitler: A Psychological Interpretation of His Views on Architecture, Art and Music, p. 76. Bowling Green State University Popular Press. ISBN 0-87972-488-9.