CD31

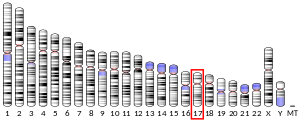

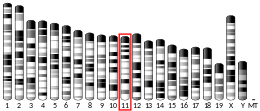

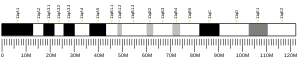

Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM-1) also known as cluster of differentiation 31 (CD31) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the PECAM1 gene found on chromosome17q23.3.[5][6][7][8] PECAM-1 plays a key role in removing aged neutrophils from the body.

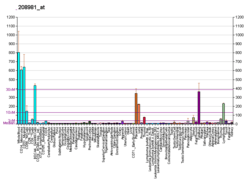

Tissue distribution

CD31 is normally found on endothelial cells, platelets, macrophages and Kupffer cells, granulocytes, lymphocytes (T cells, B cells, and NK cells), megakaryocytes, and osteoclasts.

CD31 is also expressed in certain tumors, including epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma, other vascular tumors, histiocytic malignancies, and plasmacytomas. It is rarely found in some sarcomas, such as Kaposi's sarcoma,[9][10] and carcinomas.

Immunohistochemistry

In immunohistochemistry, CD31 is used primarily to demonstrate the presence of endothelial cells in histological tissue sections. This can help to evaluate the degree of tumor angiogenesis, which can imply a rapidly growing tumor. Malignant endothelial cells also commonly retain the antigen, so that CD31 immunohistochemistry can also be used to demonstrate both angiomas and angiosarcomas. It can also be demonstrated in small lymphocytic and lymphoblastic lymphomas, although more specific markers are available for these conditions.[11]

Function

PECAM-1 is found on the surface of platelets, monocytes, neutrophils, and some types of T-cells, and makes up a large portion of endothelial cell intercellular junctions. The encoded protein is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily and is likely involved in leukocyte transmigration, angiogenesis, and integrin activation.[5] CD31 on endothelial cells binds to the CD38 receptor on natural killer cells for those cells to attach to the endothelium.[12][13]

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000261371 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000020717 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Entrez Gene: platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule".

- Newman PJ, Berndt MC, Gorski J, White GC, Lyman S, Paddock C, Muller WA (March 1990). "PECAM-1 (CD31) cloning and relation to adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily". Science. 247 (4947): 1219–22. doi:10.1126/science.1690453. PMID 1690453.

- Gumina RJ, Kirschbaum NE, Rao PN, vanTuinen P, Newman PJ (June 1996). "The human PECAM1 gene maps to 17q23". Genomics. 34 (2): 229–32. doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0272. PMID 8661055.

- Xie Y, Muller WA (October 1996). "Fluorescence in situ hybridization mapping of the mouse platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM1) to mouse chromosome 6, region F3-G1". Genomics. 37 (2): 226–8. doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0546. PMID 8921400.

- Ganjei-Azar, Parvin (2007). Color Atlas of Immunocytochemistry in Diagnostic Cytology. [New York]: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. p. 47. ISBN 978-0387-32121-9.

- Paolo Gattuso, ed. (2010). Differential diagnosis in surgical pathology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-4160-4580-9.

- Leong, Anthony S-Y; Cooper, Kumarason; Leong, F Joel W-M (2003). Manual of Diagnostic Cytology (2 ed.). Greenwich Medical Media, Ltd. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-84110-100-2.

- Zambello R, Barilà G, Sabrina Manni S (2020). "NK cells and CD38: Implication for (Immuno)Therapy in Plasma Cell Dyscrasias". CELLS. 9 (3): 768. doi:10.3390/cells9030768. PMC 7140687. PMID 32245149.

- Glaría E, Valledor AF (2020). "Roles of CD38 in the Immune Response to Infection". CELLS. 9 (1): 228. doi:10.3390/cells9010228. PMC 7017097. PMID 31963337.

Further reading

- Jackson DE (2003). "The unfolding tale of PECAM-1". FEBS Lett. 540 (1–3): 7–14. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00224-2. PMID 12681475.

- Newman PJ, Newman DK (2004). "Signal transduction pathways mediated by PECAM-1: new roles for an old molecule in platelet and vascular cell biology". Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23 (6): 953–64. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000071347.69358.D9. PMID 12689916.

- Ilan N, Madri JA (2004). "PECAM-1: old friend, new partners". Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15 (5): 515–24. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00100-5. PMID 14519385.

- Wong MX, Jackson DE (2004). "Regulation of B cell activation by PECAM-1: implications for the development of autoimmune disorders". Curr. Pharm. Des. 10 (2): 155–61. doi:10.2174/1381612043453504. PMID 14754395.

- Kalinowska A, Losy J (2007). "PECAM-1, a key player in neuroinflammation". Eur. J. Neurol. 13 (12): 1284–90. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01640.x. PMID 17116209.

- Stockinger H, Gadd SJ, Eher R, Majdic O, Schreiber W, Kasinrerk W, Strass B, Schnabl E, Knapp W (1991). "Molecular characterization and functional analysis of the leukocyte surface protein CD31". J. Immunol. 145 (11): 3889–97. PMID 1700999.

- Albelda SM, Muller WA, Buck CA, Newman PJ (1991). "Molecular and cellular properties of PECAM-1 (endoCAM/CD31): a novel vascular cell-cell adhesion molecule". J. Cell Biol. 114 (5): 1059–68. doi:10.1083/jcb.114.5.1059. PMC 2289123. PMID 1874786.

- Simmons DL, Walker C, Power C, Pigott R (1990). "Molecular cloning of CD31, a putative intercellular adhesion molecule closely related to carcinoembryonic antigen". J. Exp. Med. 171 (6): 2147–52. doi:10.1084/jem.171.6.2147. PMC 2187965. PMID 2351935.

- Kirschbaum NE, Gumina RJ, Newman PJ (1995). "Organization of the gene for human platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 shows alternatively spliced isoforms and a functionally complex cytoplasmic domain". Blood. 84 (12): 4028–37. PMID 7994021.

- Tang DG, Chen YQ, Newman PJ, Shi L, Gao X, Diglio CA, Honn KV (1993). "Identification of PECAM-1 in solid tumor cells and its potential involvement in tumor cell adhesion to endothelium". J. Biol. Chem. 268 (30): 22883–94. PMID 8226797.

- Behar E, Chao NJ, Hiraki DD, Krishnaswamy S, Brown BW, Zehnder JL, Grumet FC (1996). "Polymorphism of adhesion molecule CD31 and its role in acute graft-versus-host disease". N. Engl. J. Med. 334 (5): 286–91. doi:10.1056/NEJM199602013340502. PMID 8532023.

- Lu TT, Yan LG, Madri JA (1996). "Integrin engagement mediates tyrosine dephosphorylation on platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (21): 11808–13. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.21.11808. PMC 38140. PMID 8876219.

- Almendro N, Bellón T, Rius C, Lastres P, Langa C, Corbí A, Bernabéu C (1997). "Cloning of the human platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 promoter and its tissue-specific expression. Structural and functional characterization". J. Immunol. 157 (12): 5411–21. PMID 8955189.

- Jackson DE, Ward CM, Wang R, Newman PJ (1997). "The protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 binds platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) and forms a distinct signaling complex during platelet aggregation. Evidence for a mechanistic link between PECAM-1- and integrin-mediated cellular signaling". J. Biol. Chem. 272 (11): 6986–93. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.11.6986. PMID 9054388.

- Famiglietti J, Sun J, DeLisser HM, Albelda SM (1997). "Tyrosine residue in exon 14 of the cytoplasmic domain of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1/CD31) regulates ligand binding specificity". J. Cell Biol. 138 (6): 1425–35. doi:10.1083/jcb.138.6.1425. PMC 2132561. PMID 9298995.

- Deaglio S, Morra M, Mallone R, Ausiello CM, Prager E, Garbarino G, Dianzani U, Stockinger H, Malavasi F (1998). "Human CD38 (ADP-ribosyl cyclase) is a counter-receptor of CD31, an Ig superfamily member". J. Immunol. 160 (1): 395–402. PMID 9551996.

- Coukos G, Makrigiannakis A, Amin K, Albelda SM, Coutifaris C (1999). "Platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 is expressed by a subpopulation of human trophoblasts: a possible mechanism for trophoblast-endothelial interaction during haemochorial placentation". Mol. Hum. Reprod. 4 (4): 357–67. doi:10.1093/molehr/4.4.357. PMID 9620836.

- Cao MY, Huber M, Beauchemin N, Famiglietti J, Albelda SM, Veillette A (1998). "Regulation of mouse PECAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation by the Src and Csk families of protein-tyrosine kinases". J. Biol. Chem. 273 (25): 15765–72. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.25.15765. PMID 9624175.

- Ma L, Mauro C, Cornish GH, Chai JG, Coe D, Fu H, Patton D, Okkenhaug K, Franzoso G, Dyson J, Nourshargh S, Marelli-Berg FM (2010). "Ig gene-like molecule CD31 plays a nonredundant role in the regulation of T-cell immunity and tolerance". PNAS. 107 (45): 19461–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011748107. PMC 2984185. PMID 20978210.

External links

- Human CD Antigen Chart (eBioscience)

- Mouse CD Antigen Chart (eBioscience)

- Human PECAM1 genome location and PECAM1 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P16284 (Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule) at the PDBe-KB.