Origin hypotheses of the Croats

The origin of the Croats before the great migration of the Slavs is uncertain. The modern Croats are considered a Slavic people, which support anthropological and genetical studies, but the archaeological and other historic evidence on the migration of the Slavic settlers, the character of the native population on the present-day territory of Croatia, and their mutual relationship show diverse historical and cultural influences.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Croatia |

|

|

Early history

|

|

Middle Ages

|

|

Modernity |

|

Contemporary Croatia |

| Timeline |

|

|

Croatian ethnogenesis

The definition of Croatian ethnogenesis begins with the definition of ethnicity,[1] according to which an ethnic group is a socially defined category of people who identify with each other based on common ancestral, social, cultural or other experience, and which shows a certain durability over the long period term of time.[2] In the Croatian case, there is no doubt that in the Early Middle Ages a certain group identified themselves by ethnonym Hrvati (Croats), and was identified as such by the others.[3] It also had a political connotation, it continued to expand, and since the Late Middle Ages explicitly identified with the nation, although not in the exact meaning as of the contemporary modern nation.[3]

In the case of the present-day Croatian nation it could be said that several components or phases influenced its ethnogenesis:

- the indigenous prehistoric component which dates from Stone Age, before 40,000 years, and the younger Neolithic culture like Danilo dated 4700-3900 BC, and Eneolithic culture like Vučedol dated 3000 and 2200 BC.[4]

- the protohistoric component, which includes ancient people like Illyrians (including the Dalmatae and Liburnians in coastal Croatia, and the Pannonii in continental Croatia); Celtic or mixed Celtic-Illyrian people, such as the Iapydes, Taurisci and Scordisci also existed for a time in continental Croatia.[4] In the 4th century BCE there also existed a few Greek colonies on the Adriatic islands and coast.[4]

- the classical antiquity component caused by the Roman conquest, which included a mixture of ancient Illyrian people and Rome's colonists and legionaries;[5] there was also a temporary presence of Iranian-speaking Iazyges on the border of Roman Dalmatia at this time.[6]

- the Late Antiquity-Early Middle Ages component from the Migration Period, started by the Huns, and which in Croatia included in the first phase Visigoths and Suebi, who didn't stay for a long period of time, and Ostrogoths, Gepids and Langobards, who formed the brief Ostrogothic Kingdom (493-553 AD).[7] In the second phase occurred the great Slav migration, often associated with the Avars' activity.[7] A large part of the agricultural population of Dalmatia at the time was descended from Vlachs or Morlachs, a formerly Latin-speaking population.[8]

- the final Middle Ages-Modern Age component, which included the presence of Magyars/Hungarians, Italians/Venetians, and Germans/Saxons.[7] After the 14th century, because of the black death, and the late 15th century, because of Ottoman invasion, the Croatian ethnonym expanded from the historic Croatian lands to Western Slavonia, which caused Zagreb to become capital city of the Croatian Kingdom, and to become incorporated with the population ethnogenesis of that territory.[7] The Ottoman invasion caused many migrations of the people in the Balkans and in Croatia, like those of the Serbs and Vlachs,[9] but the upcoming world wars and social events also influenced the Croatian ethnogenesis.[9]

Old historical sources

The mention of the Croatian ethnonym Hrvat for a specific tribe before the 9th century is not yet completely confirmed. According to Constantine VII's work De Administrando Imperio (10th century), a group of Croats separated from the White Croats who lived in White Croatia and arrived by their own will, or were called by the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (610-641), to Dalmatia where they fought and defeated the Avars, and eventually organized their own principality.[10] According to the legend preserved in the work, they were led by five brothers Κλουκας (Kloukas), Λόβελος (Lobelos), Κοσέντζης (Kosentzis), Μουχλώ (Mouchlo), Χρωβάτος (Chrobatos), and two sisters Τουγά (Touga) and Βουγά (Bouga),[10][11] and their archon at the time was father of Porga, and they were baptized during the rule of Porga in the 7th century.[12]

The old historical sources do not give an exact indication of the ethnogenesis of these early Croats. Constantine VII does not identify Croats with Slavs, nor does he point to differences between them.[13] John Skylitzes in his work Madrid Skylitzes identified Croats and Serbs as Scythians. Nestor the Chronicler in his Primary Chronicle identified White Croats with West Slavs along Vistula river, with other Croats included in the East Slavic tribal union. The Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja identifies Croats with the Goths who remained after king Totila occupied the province of Dalmatia.[14] Similarly, Thomas the Archdeacon in his work Historia Salonitana mentions that seven or eight tribes of nobles, which he called "Lingones", arrived from present-day Poland and settled in Croatia under Totila's leadership.[14]

Research history

The Croatian ethnonym Hrvat, as well of those five brothers and sisters and the early ruler Porga, are not considered to be of Slavic origin, yet again, are quite original to be a pure fabrication of Constantine VII.[15][16] As such, the origin of the early Croats before and at the time of arrival to the present day Croatia, as well their ethnonym, were an eternal topic of historiography, linguistics and archeology.[15] However, the theories were often elaborated in non-scientific terms, supported by specific ideological intentions, and often by political and cultural intentions of the time.[17] This kind of interpretations caused a lot of damage to certain theories and actual scientific community.[17] It should be taken into serious consideration whether the origin of the early Croatian tribes can be regarded also as the origin of Croatian nation, and can only be asserted that the Croats as are known today as a nation became only when Croatian tribes arrived in the territory of present-day Croatia.[18]

Slavic theory

The Slavic, also known as Pan-Slavic and Autochthonous-Slavic theory, dates back to the Croatian Renaissance, when was supported by Vinko Pribojević and Juraj Šižgorić.[14] There's no doubt that Croatian language belongs to the Slavic languages, but they considered that Slavs were autochthonous in Illyricum and their ancestors were old Illyrians.[14] It developed among the Dalmatian humanists,[19] and was also considered by early modern writers, like Matija Petar Katančić, Mavro Orbini and Pavao Ritter Vitezović.[19] This cultural and romanticist idea was especially promoted by the national Illyrian Movement and their leader Ljudevit Gaj in the 19th century.[19]

With the development of Croatian historiography, since the 17th century, the Slavic theory was elaborated in more realistic terms, and considered Croats as one of the Slavic groups which settled in their modern-day homeland during the migration period.[14] Constantine the VII's work was particularly researched by the 17th century historian Ivan Lučić,[14][20] who concluded that the Croats came from White Croatia on the other side of the Carpathian mountains, in "Sarmatia" (Poland), with which historians today agree upon.[14] The autochthonous idea, that the Slavs came to Illyricum from Poland is of even older origin (12th century).[19]

In the late 19th century, the most significant impact on the future historiography had Franjo Rački, and the intellectual and political circle around Josip Juraj Strossmayer.[20] Rački's view of the unified arrival of the Croats and Serbs to the "partially empty house",[21] fit the ideological Yugoslavism and Pan-Slavism.[21] The ideas by Rački were furtherly developed by historian Ferdo Šišić in his seminal work History of the Croats in the Age of the Croat Rulers (1925).[22] The work is considered as the foundation stone for later historiography.[22] However, in the first and second Yugoslavia, the Pan-Slavic (pure-Slavic) theory was particularly emphasized because of the political context and was the only officially accepted theory by the regime,[23][24][25] while others which attributed non-Slavic origin and components were ignored and not accepted,[24][25] and even their supporters, because of also political reasons, were persecuted (Milan Šufflay, Kerubin Šegvić, Ivo Pilar and Mihovil Lovrić).[26][25] The official theory also ignored some historical sources, like the account of Constantine VII, and considered that the Croats and Serbs were the same Slavic people who arrived in one and the same migration, and unwilling to consider foreign elements in those separate societies.[27] There were Yugoslavian scholars like Ferdo Šišić and Nada Klaić who allowed limited non-Slavic origin of certain elements in Croatian ethnogenesis, and they were usually connected with the Avars and Bulgars.[24][28] One of the main difficulties with the Pan-Slavic theory was the Croatian (and Serbian) ethnonym which could not be derived from the Slavic language.[14]

According to the autochthonous model, the Slavs homeland was in the area of former Yugoslavia, and they spread northwards and westwards rather than the other way round.[29] A revision of the theory, developed by Ivan Mužić, argues that Slavic migration from the north did happen, but the actual number of Slavic settlers was small and that the autochthonous ethnic substratum was prevalent in the formation of the Croats, but that contradicts and doesn't answer the presence of predominant Slavic language.[29][19] The social and linguistical situation that made the pre-Slavic population is hard to reconstruct, especially if one accepts the theory that the autochthonous population was dominant at the time of the arrival of the Slavs yet accepted the language and culture of Slavic newcomers who were in the minority.[30] This scenario can only be explained with the possible distortion of the cultural and ethnic identity of the native Romanized population that happened after the fall of West Roman Empire, and that the new Slavic language and culture was seen as a prestigious idiom they had to, or wanted to accept.[30] The assumptions that the Illyrians were an ethnolinguistic homogeneous entity were rejected in the 20th century, and according to the scholars who support the Danube basin hypothesis of the Slavic homeland, it is considered that some proto-Slavic tribes existed even before the Slavic migration in the Balkans.[31]

Gothic theory

The Gothic theory, which dates back to the late 12th and 13th century work by Priest of Duklja and Thomas the Archdeacon,[28][32] without excluding that some Gothic segments could survive the collapse of Gothic Kingdom and were included in Croatian ethnogenesis, is based on almost none concrete evidence to identify Croats with the Goths.[28][32] In 1102, Croatian Kingdom entered a personal union with Kingdom of Hungary. It is considered that this identification of Croats with Goths is based on a local Croatian Trpimirović dynastic myth from the 11th century, paralleling Hungarian Árpád dynasty's myth of originating from the Hunnic leader Attila.[28][33]

Some scholars like Nada Klaić considered that Thomas the Archdeacon despised Slavs/Croats and that wanted to depreciate them as barbarians with Goths identification, however, until the time of Renaissance the Goths were seen as noble barbarians compared to Huns, Avars, Vandals, Langobards, Magyars and Slavs, and as such he would not identify them with the Goths.[34][35] Also, in the Thomas the Archdeacon's work the starting emphasis is on the decadence of people from Salona, and as such scholars consider the emergence of newcomers Goths/Croats was actually seen as a kind of God's scourge for sinful Romans.[36][35]

Scholars like Ludwig Gumplowicz and Kerubin Šegvić literally read the medieval works and considered Croats as Goths who were eventually Slavicized, and that the ruling caste was formed from the foreign warrior element.[24][37] The idea was argued with the Gothic suffix mære (mer, famous) found among the names of Croatian dukes on stone and written inscriptions, as well Slavic suffix slav (famous), and that mer eventually was changed with mir (peace) because the Slavs twisted the interpretation of the names according their language.[38] The ethnonym Hrvat was derived from the Germanic-Gothic Hrôthgutans, the hrōþ (victory, glory) and gutans (common historical name for the Goths).[39] The Gothic theory, as well as Pan-Slavic during Yugoslavia, was the only supported theory by the regime of NDH.[24][32]

Avar theory

Avar, also known as Avar-Bulgarian, Bulgarian or Turkic theory, dates to the late 19th and early 20th century when John Bagnell Bury noted the similarity between Croatian legend of five brothers (and two sisters) with Bulgarian legend of Kubrat's five sons.[14] He considered that the White Croats' Chrobatos and Bulgars' Kubrat were the same person from the Bulgars ethnic group, as well derived the Croatian title Ban from the personal name of Avar khagan Bayan I and Kubrat's son Batbayan.[14] Similarly Henry Hoyle Howorth asserted that the White Croats were a Bulgar warrior caste to whom was given land in the Western Balkans due to expulsion of the Pannonian Avars following the revolt of Kubrat against the Avar Khaganate.[40]

The theory was later developed by Otto Kronsteiner in 1978.[24][41] He tried to prove that early Croats were an upper caste of Avar origin, which blended with Slavic nobility during the 7th and 8th century and abandoned their Avar language.[42] As arguments for his thesis he considered the Tatar-Bashkir derivation of Croatian ethnonym;[42] that Croats and Avars are almost always mentioned together;[42] distribution of Avarian type of settlements where the Croatian ethnonym was as toponym, pagus Crouuati in Carinthia and Kraubath in Styria;[42] this settlements had Avarian names with suffix *-iki (-itji);[42] the commander of those settlements was Avarian Ban which name is located in the center of those settlements, Faning/Baniče < Baniki in Carinthia, and Fahnsdorf < Bansdorf in Styria;[42] the Avarian officers titles, besides Mong.-Turk. Khagan, the Kosezes/Kasazes, Ban and Župan.[42] Previously, by some Yugoslavian historians the toponym Obrov(ac) was also considered of Avar origin,[43] and according to Kronsteiner's claims, which many Nada Klaić accepted, Klaić moved the ancient homeland of White Croats to Carantania.[42]

However, according to Peter Štih and modern scholars, Kronsteiner arguments were plain assumptions which historians can not objectively accept as evidence.[44] Actually, the etymology derivation is one of many, and is not generally accepted;[45][46] the Croats are mentioned along the Avars only in the Constantine VII's work, but always as enemies of the Avars, who destroyed and expelled their authority from Dalmatia;[47] those settlements had widespread Slavic suffix ići, the settlements do not have the semicircular Avar type arrangement, and the Ban's settlements could not be his seat as are very small and are not found on any important crossroad or geographical location;[48] the titles origin and derivation are unsolved, and they are not found among Avars and Avar language;[48][49] toponyms with root Obrov derive from South Slavic verb "obrovati" (to dig a trench) and are mostly of later date (from the 14th century).[43]

The theory was further developed by Walter Pohl.[50] He noted the difference between infantry-agricultural (Slavic) and cavalry-nomadic (Avar) tradition, but did not negate that sometimes the situation was exactly the opposite, and often sources did not differentiate Slavs and Avars.[51][52] He initially shared the Bury's opinion on the Kubrat's and Chrobatos' name and legends, and the mention of two sisters interpreted as additional elements which joined the alliance "by the maternal line", and noted that the symbolism of the number seven is often encountered in the steppe peoples.[53] Pohl noted that the Kronsteiner's merit was that, instead of the previously usual "ethnic" ethnogenesis, he proposed a "social" one.[53] As such, Croatian name would not be an ethnonym, but a social designation for a group of elite warriors of diverse origin which ruled over the conquered Slavic population on the Avar Khaganate's boundary,[53][50] the designation eventually becoming an ethnonym[53] imposed to the Slavic groups.[54] The assertion about the boundary is only partly true because although the Croats were mentioned on the line of Khaganate they were mostly outside and not inside the boundaries.[55] He did not support Kronstenier's derivation, nor consider the etymology important as it is impossible to establish the ethnic origin of "original Croats", i.e. the social categories which carried the title of "Hrvat".[53]

Historians and archaeologists until now concluded that Avars never lived in Dalmatia proper (including Lika) yet somewhere in Pannonia,[56][57] there is lack of authentic early Avar archaeological findings within Croatia, and that Turkic ethnic component was negligible.[58] Lately, a more pro-Turkic (as White Oghurs) thesis was given by Osman Karatay.[59] This theory is not taken into consideration as it frequently disregarded existing historiographical scholarship.[60] It also considered the Turkic origin of Bosnian polity, which is viewed as an attempt of popularisation of links between Bosnian Muslims with Turkey.[60]

Iranian theory

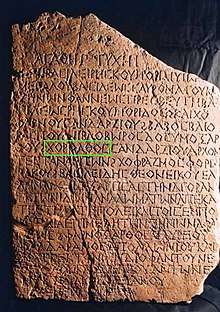

The Iranian, also known as Iranian-Caucasian theory, dates to the 1797 and the doctoral dissertation by Josip Mikoczy-Blumenthal who, as the dissertation mysteriously disappeared in 1918 and was preserved only a short review, considered that Croats originated from Sarmatians who were descending from Medes in North-Western Iran.[61] In 1853 were discovered the two Tanais Tablets.[62] They are written in Greek, and were founded in the Greek colony of Tanais in the late 2nd and early 3rd century AD, at the time when the colony was surrounded by Sarmatians.[63][64] On the larger inscription is written the father of the devotional assembly Horouathon and the son of Horoathu, while on the smaller inscription Horoathos, the son of Sandarz, the archons of the Tanaisians,[62] which resembles the usual variation of Croatian ethnonym Hrvat - Horvat.[62] Some scholars use these tablets only to explain the etymology, and not necessarily the ethnogenesis.[34]

The Iranian theory entered the historical science from three, initially independent ways, from historical-philological, art history, and religion history, in the first half of the 20th century.[65] The last two were supported by art historian scholars (Luka Jelić, Josef Strzygowski, Ugo Monneret de Villard),[66] and religion historian scholars (Johann Peisker, Milan Šufflay, Ivo Pilar).[67] The Slavic-Iranian cultural interrelation was pointed out by modern ethnologists, like Marijana Gušić who in the ritual Ljelje noticed the influence from Pontic-Caucasian-Iranian sphere,[68][69] Branimir Gušić,[69] and archeologists Zdenko Vinski and Ksenija Vinski-Gasparini.[70] However, the cultural and artistic indicators of Iranian origin, including indications in the religious sphere, is somehow difficult to determine.[64] It is mostly Sassanian (224-651 AD) influences that were felt in the steppe regions.[64]

The first scholar who connected the tablets names with Croatian ethnonym was A. L. Pogodin in 1902.[71][64] First who considered such a thesis and Iranian origin was Konstantin Josef Jireček in 1911.[65] Ten years later, Al. I. Sobolevski gave the first systematic theory about the Iranian origin which until today did not change in basic lines.[65] In the same year, independently Fran Ramovš, with reference to the Iranian interpretation of the name Horoathos by Max Vasmer, concluded that the early Croats were one of the Sarmatian tribes which during the great migration advanced along the outer edge of Carpathians (Galicia) to the Vistula and Elbe rivers.[65] The almost final, and more in detail picture was given by Slovenian academic Ljudmil Hauptmann in 1935.[65] He considered that Iranian Croats, after the Huns invasion around 370 when the Huns crossed the Volga river and attacked the Iranian Alans at the Don river, abandoned their initial Sarmatian lands and arrived among the Slavs at the waste lands north of Carpathians, where they gradually Slavicized.[72] There they belonged to the Antes tribal polity until the Antes were attacked by the Avars in 560, and the polity was finally destroyed 602 by the same Avars.[72] The thesis was subsequently supported by Francis Dvornik, George Vernadsky, Roman Jakobson, Tadeusz Sulimirski, and Oleg Trubachyov.[73] In 1985, Omeljan Pritsak considered early Croats a clan of Alan-Iranian origin which during the "Avarian pax" had frontiersman-merchant social role.[74]

The personal names on the Tanais Tablets are considered as a prototype of a certain ethnonym of a Sarmatian tribe those persons did descend from,[63][45] and as well today is generally accepted that the Croatian name is of Iranian origin and that can be traced to the Tanais Tablets.[45][46] However, the etymology itself is not enough strong evidence.[63] The theory is further explained with the Avar's destruction of Antes tribal polity in 602, and that the early Croats migration and subsequent war with Avars in Dalmatia (during the reign of Heraclius 610-641) can be seen as a continuation of the war between Antes and Avars.[71] That the early Croats marked the cardinal directions with colors, hence White Croats and White Croatia (Western) and Red Croatia (Southern),[71] but the cardinal color designation, in general, indicates remnants of the widespread steppe peoples tradition.[75] The heterogeneous composition of the Croatian legend in which are unusually mentioned two women leaders Touga and Bouga, which indicates to what the actual archaeological findings confirmed - the existence of "warrior women" known as Amazons among the Sarmatians and Scythians.[71] As such, Trubachyov tried to explain the original proto-type of the ethnonym from adjectives *xar-va(n)t (feminine, rich in women), which derives from the etymology of Sarmatians, the Indo-Aryan *sar-ma(n)t (feminine), in both Indo-Iran adjective suffix -ma(n)t/wa(n)t, and Indo-Aryan and Indo-Iranian word *sar- (woman), which in Iranian gives *har.[45]

Another interpretation was given by the scholar Jevgenij Paščenko; he considered that the Croats were a heterogeneous group of people belonging to the Chernyakhov culture, a poly-ethnic cultural mélange of mostly Slavs and Sarmatians, but also Goths, Getae and Dacians.[76] There was happening an interrelation between Slavic and Iranian language and culture, seen for example in the toponymy.[76] As such, under the ethnonym Hrvati should not be necessary seen a specific or even homogeneous tribe, yet archaic religion and mythology of a heterogeneous group of people of Iranian origin or influence who worshiped the solar deity Hors, from which possibly originates the Croatian ethnonym.[77]

The another known more radical thesis of the Iranian theory was by Stjepan Krizin Sakač, who although gave insights on some issues, tried to follow the Croatian ethnonym as far the region Arachosia (Harahvaiti, Harauvatiš) and its people (Harahuvatiya) of the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE).[78][71][79] However, although the suggestive similarity, it is etymologically incorrect.[80] There were many supporters of the thesis and further tried to develop it, but the actual arguments are considered far-fetched and unscientific.[71][67][81]

Anthropological and genetic studies

Anthropology

Anthropologically, the craniometrical measurements made on the contemporary Croatian population of the city of Zagreb showed it predominantly has "dolichocephalic head type and the mesoprosopic face type", more specifically mesocephalia and leptoprosopia prevail in South Dalmatia, and brachycephaly and euryprosopy in Central Croatia.[82] According to the 1998-2004 craniometric study of medieval Central European archaeological sites, four Dalmatian and two Bosnian sites clustered with Polish sites, two Continental Croatia (Avaro-Slav) sites were classified into the cluster of Hungarian sites west of the Danube, while the two sites from the Bijelo Brdo culture were into the cluster of Slav sites from Austria, the Czech Republic, and Slovenia. Comparison to the Scythian-Sarmatian sites did not reveal significant similarity in cranial morphology, nor was supported the idea of the Avar frontiersmen. The results indicate that the nucleus of the early Croat state in Dalmatia was of Slavic ancestry, which arrived from the area somewhere in Poland probably along the direct route Nitra (Slovakia)-Zalaszabar (Hungary)-Nin, Croatia, and gradually expanded into the continental hinterland of Bosnia and Herzegovina by the 10th century, however, by the end of the 11th century did not in Eastern Slavonia.[83][84][85] The 2015 study of medieval skeletal remains in Šopot (14th-15th century) and Ostrovica (9th century) found out they cluster with other Dalmatian sites as well Polish sites, concluding that "PCA showed that all Eastern Adriatic coast sites were closely related in cranial morphology, and thus, most likely had similar biological makeup".[86]

Population genetics

Genetically, on the Y chromosome line, a majority (>85%) of male Croats from Croatia belong to one of the three major European Y-DNA haplogroups - I (38%[87][88][89]-44%[90]), R1a (27%[90]-34%[87][88][89]) and R1b (12.4%[90]-15%[87][88][89]), while a minority (>15%) mostly belongs to haplogroup E (9%[90]), and others to haplgroups J (4.4%[90]), N (2%[90]), and G (1%[90]). The distribution, variance and frequency of the I and R1a subclades (>65%) among Croats is related to the medieval Slavic expansion, most probably from the territory of present day Ukraine and Southeastern Poland.[91][92][93][94][95] Genetically, on the maternal X chromosome line, a majority (>65%) of female Croats from Croatia (mainland and coast) belong to three of the eleven major European mtDNA haplogroups - H (45%), U (17.8-20.8%), J (3-11%), while a large minority (>35%) belongs to many other smaller haplogroups.[96] Based on autosomal IBD survey the speakers of Serbo-Croatian language share a very high number of common ancestors dated to the migration period approximately 1,500 years ago with Poland and Romania-Bulgaria clusters among others in Eastern Europe. It was caused by the Slavic expansion, a small population which expanded into regions of "low population density beginning in the sixth century" and that it is "highly coincident with the modern distribution of Slavic languages".[97]

The region of modern-day Croatia may have served as a refugium for the northern populations during the last glacial maximum (LGM).[90] The eastern Adriatic coast was much further south.[88] The northern and the western parts of that sea were steppes and plains, while the modern Croatian islands (rich in Paleolithic archeological sites) were hills and mountains.[88][90] The region had a specific role in the structuring of European, and particularly among Slavic, paternal genetic heritage, characterized by the predominance of R1a and I, and scarcity of E lineages.[89] Genetical results can not be used as the evidence for a specific ethnic component, but they indicate the main role of the Slavs in the Croatian ethnogenesis.[98]

Notes

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 251.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 251-252.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 252.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 253.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 253-254.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 256.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 254.

- Stanko Guldescu, The Croatian-Slavonian Kingdom: 1526-1792, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 1970, p.70, ISBN 9783110881622

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 254-255.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 258.

- Živković 2012, p. 113.

- Živković 2012, p. 54-56, 140.

- Goldstein, Ivo (1995). Hrvatski rani srednji vijek [Croatian Early Middle Age] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Novi Liber. p. 23. ISBN 953-6045-02-8.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 259.

- Heršak, Lazanin 1999, p. 20.

- Živković 2012, p. 54-55, 114-115.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 260-262.

- Katičić 1999, p. 15-16.

- Džino 2010, p. 17.

- Džino 2010, p. 18.

- Džino 2010, p. 18–19.

- Džino 2010, p. 19.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 259, 261.

- Heršak, Lazanin 1999, p. 27.

- Bartulin 2013, p. 224.

- Stagličić, Ivan (23 November 2010). "Gdje su Hrvati disali prije "stoljeća sedmog"?" [Where did Croats breath before "seventh century"?]. Zadarski list (in Croatian). Zadar. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- John Van Antwerp Fine (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. pp. 53, 56–57. ISBN 9780472081493.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 261.

- Katičić, Radoslav (1991), "Ivan Mužić o podrijetlu Hrvata" [Ivan Mužić about origin of Croats], Starohrvatska Prosvjeta (in Croatian), III (19): 250, 255–259

- Matasović 2008, p. 46.

- Szabo 2002, p. 7–36.

- Džino 2010, p. 20.

- Heršak, Lazanin 1999, p. 22.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 260.

- Heršak, Lazanin 1999, p. 21-22.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 260-261.

- Bartulin 2013, p. 117–118.

- Tafra 2003, p. 16-18.

- Bartulin 2013, p. 118.

- Howorth, H.H. (1882). "The Spread of the Slaves - Part IV". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 11: 224.

- Džino 2010, p. 21.

- Heršak, Lazanin 1999, p. 28.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 257.

- Štih 1995, p. 127.

- Gluhak, Alemko (1990), Podrijetlo imena Hrvat [The origin of the ethnonym Hrvat] (in Croatian), Zagreb: Jezik (Croatian Philological Society), pp. 131–133

- Matasović, Ranko (2008), Poredbenopovijesna gramatika hrvatskoga jezika [A Comparative and Historical Grammar of Croatian] (in Croatian), Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, p. 44, ISBN 978-953-150-840-7

- Štih 1995, p. 128.

- Štih 1995, p. 130.

- Živković 2012, p. 144, 145.

- Džino 2010, p. 20–21, 47.

- Heršak, Lazanin 1999, p. 28-29.

- Pohl 1995, p. 88-90.

- Heršak, Lazanin 1999, p. 29.

- Džino 2010, p. 21, 47.

- Budak 2018, pp. 101.

- Živković 2012, p. 51, 117-118.

- Sokol, Vladimir (2008), "Starohrvatska ostruga iz Brušana u Lic: Neki rani povijesni aspekti prostora Like – problem banata" [An early Croatian spur from Brušani in Lika: Some early historical aspects of the Lika region - the “banat” problem], "Arheološka istraživanja u Lici" i "Arheologija peći i krša" Gospić, 16.-19. listopada 2007., 23, Zagreb-Gospić: Izdanja Hrvatskog arheološkog društva, pp. 185–187, ISBN 978-953-7637-02-6

- Sedov 2012, p. 447.

- Heršak, Silić 2002, p. 213.

- Džino 2010, p. 22.

- Stagličić, Ivan (27 November 2008). "Ideja o iranskom podrijetlu traje preko dvjesto godina" [Idea about Iranian theory lasts over two hundred years]. Zadarski list (in Croatian). Zadar. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Škegro, Ante (2005), Two Public Inscriptions from the Greek Colony of Tanais at the Mouth of the Don River on the Sea of Azov, I, Review of Croatian History, pp. 9, 15, 21–22, 24

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 262.

- Heršak, Lazanin 1999, p. 26.

- Košćak 1995, p. 110.

- Košćak 1995, p. 111-112.

- Košćak 1995, p. 112.

- Lozica, Ivan (2000), Kraljice u Akademiji [Kraljice [Queens] in Academy], 37, Narodna umjetnost: Croatian Journal of Ethnology and Folklore Research, p. 69

- Košćak 1995, p. 114.

- Košćak 1995, p. 114-115.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 263.

- Košćak 1995, p. 111.

- Košćak 1995, p. 112-113.

- Košćak 1995, p. 113.

- Katičić 1999, p. 8-16.

- Paščenko 2006, p. 46-48.

- Paščenko 2006, p. 67-82, 109-111.

- Budak 2018, pp. 98–99.

- Katičić 1999, p. 11-12.

- Katičić 1999, p. 12.

- Katičić 1999, p. 15.

- Đ. Grbeša; et al. (2007), "Craniofacial Characteristics of Croatian and Syrian Populations", Collegium Antropologicum, 31 (4): 1121–1125

- M. Šlaus (1998), "Craniometric relationships of medieval Central European populations: Implications for Croat ethnogenesis", Starohrvatska Prosvjeta, 3 (25): 81–107

- M. Šlaus (2000), "Kraniometrijska analiza srednjovjekovnih nalazišta središnje Europe: Novi dokazi o ekspanziji hrvatskih populacija tijekom 10. do 13. stoljeća", Opuscula Archaeologica: Papers of the Department of Archaeology, 23–24 (1): 273–284

- M. Šlaus; et al. (2004), "Craniometric relationships among medieval Central European populations: implications for Croat migration and expansion.", Croatian Medical Journal, 45 (4): 434–444, PMID 15311416

- Bašić et al. 2015.

- Barać et al. 2003.

- Rootsi et al. 2004.

- Peričić et al. 2005.

- Battaglia et al. 2008.

- A. Zupan; et al. (2013). "The paternal perspective of the Slovenian population and its relationship with other populations". Annals of Human Biology. 40 (6): 515–526. doi:10.3109/03014460.2013.813584. PMID 23879710.

- O.M. Utevska (2017). Генофонд українців за різними системами генетичних маркерів: походження і місце на європейському генетичному просторі [The gene pool of Ukrainians revealed by different systems of genetic markers: the origin and statement in Europe] (PhD) (in Ukrainian). National Research Center for Radiation Medicine of National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. pp. 219–226, 302.

- Fóthi, E.; Gonzalez, A.; Fehér, T.; et al. (2020), "Genetic analysis of male Hungarian Conquerors: European and Asian paternal lineages of the conquering Hungarian tribes", Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 12 (1), doi:10.1007/s12520-019-00996-0

- Underhill, Peter A. (2015), "The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a", European Journal of Human Genetics, 23 (1): 124–131, doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.50, PMC 4266736, PMID 24667786

- J. Šarac; et al. (2016). "Genetic heritage of Croatians in the Southeastern European gene pool—Y chromosome analysis of the Croatian continental and Island population". AJHB. 28: 837–845. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22876. PMID 27279290.

- Cvjetan et al. 2004.

- P. Ralph; et al. (2013). "The Geography of Recent Genetic Ancestry across Europe". PLOS Biology. 11 (5): e105090. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001555. PMC 3646727. PMID 23667324.

- Heršak, Nikšić 2007, p. 264.

References

- Štih, Peter (1995), "Novi pokušaji rješavanja problematike Hrvata u Karantaniji" [New attempts to resolve the problems of Croats in Karantania], in Budak, Neven (ed.), Etnogeneza Hrvata [Ethnogenesis of Croats] (in Croatian), Matica hrvatska, ISBN 953-6014-45-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pohl, Walter (1995), "Osnove Hrvatske etnogeneze: Avari i Slaveni" [Basics of Croatian ethnogenesis: Avars and Slavs], in Budak, Neven (ed.), Etnogeneza Hrvata [Ethnogenesis of Croats] (in Croatian), Matica hrvatska, ISBN 953-6014-45-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vladimir, Košćak (1995), "Iranska teorija o podrijetlu Hrvata" [Iranian theory on the origin of Croats], in Budak, Neven (ed.), Etnogeneza Hrvata [Ethnogenesis of Croats] (in Croatian), Matica hrvatska, ISBN 953-6014-45-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heršak, Emil; Lazanin, Sanja (1999), "Veze srednjoazijskih prostora s hrvatskim srednjovjekovljem" [Connections between Central Asia and Medieval Croatia], Migration and Ethnic Themes (in Croatian), 15 (1–2)

- Katičić, Radoslav (1999), Na kroatističkim raskrižjima [At Croatist intersections] (in Croatian), Zagreb: Hrvatski studiji, ISBN 953-6682-06-0

- Heršak, Emil; Silić, Ana (2002), "Avari: osvrt na njihovu etnogenezu i povijest" [The Avars: A Review of Their Ethnogenesis and History], Migration and Ethnic Themes (in Croatian), 18 (2–3)

- Szabo, Gjuro (2002), Ivan Mužić (ed.), Starosjeditelji i Hrvati [Natives and Croats] (in Croatian), Split: Laus, ISBN 953-190-118-X

- Paščenko, Jevgenij (2006), Nosić, Milan (ed.), Podrijetlo Hrvata i Ukrajina [The origin of Croats and Ukraine] (in Croatian), Maveda, ISBN 953-7029-03-4

- Heršak, Emil; Nikšić, Boris (2007), "Hrvatska etnogeneza: pregled komponentnih etapa i interpretacija (s naglaskom na euroazijske/nomadske sadržaje)" [Croatian Ethnogenesis: A Review of Component Stages and Interpretations (with Emphasis on Eurasian/Nomadic Elements)], Migration and Ethnic Themes (in Croatian), 23 (3)

- Džino, Danijel (2010), Becoming Slav, Becoming Croat: Identity Transformations in Post-Roman and Early Medieval Dalmatia, Brill, ISBN 9789004186460

- Živković, Tibor (2012). De conversione Croatorum et Serborum: A Lost Source. Belgrade: The Institute of History.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bartulin, Nevenko (2013), The Racial Idea in the Independent State of Croatia: Origins and Theory, Brill, ISBN 9789004262829

- Budak, Neven (2018), Hrvatska povijest od 550. do 1100. [Croatian history from 550 until 1100], Leykam international, pp. 86–118, ISBN 978-953-340-061-7CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- L. Barać; et al. (2003). "Y chromosomal heritage of Croatian population and its island isolates" (PDF). European Journal of Human Genetics. 11 (7): 535–542. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200992. PMID 12825075.

- S. Rootsi; et al. (2004). "Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow in Europe" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (1): 128–137. doi:10.1086/422196. PMC 1181996. PMID 15162323.

- M. Peričić; et al. (2005). "High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of southeastern Europe traces major episodes of paternal gene flow among Slavic populations". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (10): 1964–75. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185. PMID 15944443.

- V. Battaglia; et al. (2008). "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in southeast Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 820–830. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249. PMC 2947100. PMID 19107149.

- S. Cvjetan; et al. (2004). "Frequencies of mtDNA Haplogroups in Southeastern Europe-Croatians, Bosnians and Herzegovinians, Serbians, Macedonians and Macedonian Romani". Collegium Antropologicum. 28 (1).

- P. Ralph; et al. (2013). "The Geography of Recent Genetic Ancestry across Europe". PLOS Biology. 11 (5): e105090. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001555. PMC 3646727. PMID 23667324.

- Ž. Bašić; et al. (2015). "Cultural inter-population differences do not reflect biological distances: an example of interdisciplinary analysis of populations from Eastern Adriatic coast". Croatian Medical Journal. 56 (3): 230–238. doi:10.3325/cmj.2015.56.230. PMC 4500963. PMID 26088847.

Further reading

- Pohl, Walter (1988), Die Awaren: Ein Steppenvolk in Mitteleuropa, 567–822 N. Chr. (in German), Munchen: C.H. Beck, ISBN 978-3-406-48969-3

- Tomičić, Zlatko; Lovrić, Andrija-Željko, eds. (1999), Staroiransko podrijetlo Hrvata: Zbornik simpozija Zagreb, 24. Lipnja 1998 [The Old-Iranian origin of Croats: Symposium proceedings Zagreb, 24 June 1998] (in Croatian and English), Zagreb: Cultural centre at the Embassy of I. R. Iran in Zagreb, ISBN 953-6301-07-5

- Mužić, Ivan (2001), Hrvati i autohtonost [Croats and autochthony] (in Croatian), Split: Knjigo Tisak, ISBN 953-213-034-9

- Tafra, Robert (2003), Hrvati i Goti [Croats and Goths] (in Croatian), Split: Marjan Tisak, ISBN 953-214-037-9

- Karatay, Osman (2003), In Search of the Lost Tribe: The Origins and Making of the Croation Nation, Munchen: Ayse Demiral, ISBN 975-6467-07-X

- Majorov, Aleksandr Vjačeslavovič (2012), Velika Hrvatska: etnogeneza i rana povijest Slavena prikarpatskoga područja [Great Croatia: ethnogenesis and early history of Slavs in the Carpathian area] (in Croatian), Zagreb, Samobor: Brethren of the Croatian Dragon, Meridijani, ISBN 978-953-6928-26-2