Ljudevit Gaj

Ljudevit Gaj (Croatian pronunciation: [ʎûdeʋit ɡâːj]; born Ludwig Gay;[1] 8 August 1809 – 20 April 1872) was a Croatian linguist, politician, journalist and writer. He was one of the central figures of the pan-Slavist Illyrian Movement.

Ljudevit Gaj | |

|---|---|

.png) | |

| Born | Ludwig Gay 8 August 1809 |

| Died | 20 April 1872 (aged 62) |

| Resting place | Mirogoj Cemetery, Zagreb, Croatia |

| Occupation | Linguist, politician, journalist, writer |

| Known for | Gaj's Latin alphabet |

| Movement | Illyrian movement |

| Spouse(s) | Paulina Krizmanić ( m. 1842) |

| Children | 5 |

Biography

Origin

He was born in Krapina (then in the Varaždin County, Kingdom of Croatia, Austrian Empire), on August 8, 1809. His father Johann Gay was a German immigrant from Hungarian Slovakia, and his mother was Juliana née Schmidt, the daughter of a German immigrant arriving in the 1770s.[2][3]

The Gays were originally of Burgundian Huguenot origin. They arrived to Batizovce in present-day Slovakia in 16th or 17th century. Thence they became serfs of Mariassy de Markusfalva and Batizfalva families in 18th century. As there was a lot of ethnic Germans in that area, the Gays were soon Germanised. Ljudevit's father originates from a branch that moved to the village of Markušovce.[4]

Orthography and other work

Gaj started publishing very early; his 36-page booklet on stately manors in his native district, written in his native German, appeared already in 1826 as Die Schlösser bei Krapina.[5][6]

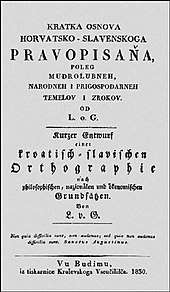

In Buda in 1830 Gaj's Latin alphabet was published [7][8] ("Concise Basis for a Croatian-Slavonic Orthography"), which was the first common Croatian orthography book (after the works of Ignjat Đurđević and Pavao Ritter Vitezović). The book was printed bilingually, in Croatian and German. The Croatians used the Latin alphabet, but some of the specific sounds were not uniformly represented. Gaj followed the example of Pavao Ritter Vitezović and the Czech orthography, using one letter of the Latin script for each sound in the language. He used diacritics and the digraphs lj and nj.

The book helped Gaj achieve nationwide fame. In 1834 he succeeded where fifteen years before Đuro Matija Šporer had failed, i.e. obtaining an agreement from the royal government of the Habsburg Monarchy to publish a Croatian daily newspaper. He was known as an intellectual leader thereafter. On 6 January 1835, Novine Horvatske ("The Croatian News") appeared, and on 10 January the literary supplement Danicza horvatzka, slavonzka y dalmatinzka ("The Croatian, Slavonian, and Dalmatian Daystar"). The "Novine Horvatske" were printed in Kajkavian dialect until the end of that year, while "Danic[z]a" was printed in Shtokavian dialect along with Kajkavian.

In early 1836 the publications' names were changed to Ilirske narodne novine ("The Illyrian People's News") and Danica ilirska ("The Illyrian Morning Star") respectively. This was because historians at the time hypothesised Illyrians had been Slavic and were the direct forefathers of the present-day South Slavs.

In addition to his intellectual work, Gaj was also a poet. His most popular poem was "Još Hrvatska ni propala" ("Croatia is not in ruin yet"), which was written in 1833.

Death

Gaj died in Zagreb, Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, Austria-Hungary, in 1872 at the age of 62.

Linguistic legacy

The Latin alphabet used in the Serbo-Croatian language is credited to Gaj's Kratka osnova Hrvatskog pravopisa. The Cyrillic counterpart is called vukovica, after contemporary linguist Vuk Karadžić. The Slovenian alphabet, introduced in the mid-1840s, is also a variation of Gaj's Latin alphabet, from which it differs by the lack of the letters ć and đ.

Personal

He married 26-year-old Paulina Krizmanić, niece of an abbott, in 1842 at Marija Bistrica. They had five children: daughter Ljuboslava, and sons Velimir, Svetoslav, Milivoje, and Bogdan.[9]

Legacy

In 2008, a total of 211 streets in Croatia were named after Ljudevit Gaj, making him the fourth most common person eponym of streets in the country.[10]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ljudevit Gaj. |

- Ognjenović, Gorana; Jozelić, Jasna (2014). Politicization of Religion, the Power of State, Nation, and Faith: The Case of Former Yugoslavia and its Successor States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 81.

- Traian Stoianovich (1994). Balkan Worlds: The First and Last Europe. M.E. Sharpe. p. 282. ISBN 9780765638519.

- Discourses of collective identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945), Vol. 2, by Balázs Trencsényi and Michal Kopeček

- Horvat, Josip. Politička povijest Hrvatske 1. August Cesarec, Zagreb, p. 49

- "Die Schloesser bei Krapina". Koha Online Catalog: ISBD View. Library of the Faculty of Philosophy, Zagreb. UDC: 94(497.5)-2. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- Đuro Šurmin (1904). Hrvatski Preporod. p. 121. ISBN 9781113014542. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- Kratka osnova horvatsko-slavenskoga pravopisanja, poleg mudroljubneh, narodneh i prigospodarneh temeljov i zrokov

- Kratka osnova horvatsko-slavenskoga pravopisaňa

- "Krapinski Vjesnik". Godina VI. Broj 58. Studeni 2009. ISSN 1334-9317

- Letica, Slaven (29 November 2008). Bach, Nenad (ed.). "If Streets Could Talk. Kad bi ulice imale dar govora". Croatian World Network. ISSN 1847-3911. Retrieved 2014-12-31.