Genetic studies on Turkish people

In population genetics, research has been conducted to study the genetic origins of the modern Turkish people (not to be confused with Turkic peoples) in Turkey. These studies sought to determine whether the modern Turks have a stronger genetic affinity with the Turkic peoples of Central Asia, from where the Seljuk Turks began migrating to Anatolia, after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, which led to the establishment of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate in the late 11th century, or whether modern Turks are instead largely descended from the indigenous peoples of Anatolia who were culturally assimilated during the Seljuk and the Ottoman periods.

The largest autosomal study of Turkish genetics (on 16 individuals) concluded that the Turkish population form a cluster with Southern European populations and that the East Asian (presumably Central Asian) legacy to the Turkish people is estimated to be 21.7%.[1] However, that is not an estimate of the number of migrants or migration rates since the original donor populations are unknown, and the exact kinship between current East Asians and the medieval Oghuz Turks is also uncertain.[2][3] Several studies have concluded that the genetic haplogroups indigenous to Western Asia form the largest part of the gene pool of the present-day Turkish population.[4][5][6][7][4][8][9][10] An admixture analysis determined that the Anatolian Turks share most of their genetic ancestry with non-Turkic populations resident in the region, and the 12th century is set as an admixture date.[11]

Central Asian and Uralic connection

The question to what extent a gene flow from Central Asia to Anatolia has contributed to the current gene pool of the Turkish people and the role of the 11th-century settlement by Oghuz Turks have been the subject of several studies. A factor that makes it difficult to give reliable estimates is the problem of distinguishing the effects of different migratory episodes. Thus, although the Turks settled in Anatolia (peacefully or by war) with cultural significance, including the introduction of the Turkish language and Islam, the genetic significance from Central Asia might have been slight, according to some studies.[6][12]

Some of the Turkic peoples originated from Central Asia and so are possibly related with the Xiongnu.[13] Most (89%) of the Xiongnu sequences can be classified as belonging to Asian haplogroups and nearly 11% belong to European haplogroups.[13] The findings indicate that the contacts between European and Asian populations were anterior to the Xiongnu culture,[13] and confirm results reported for two samples from an early 3rd century B.C. Scytho-Siberian population.[14]

According to another archaeological and genetic study in 2010, the DNA found in three skeletons in 2000-year-old elite Xiongnu cemetery in Northeast Asia belonged to C3, D4 and included R1a. The evidence of paternal R1a support the Kurgan expansion hypothesis for the Indo-European expansion from the Volga steppe region.[15] As the R1a was found in Xiongnu people[15] and the present-day people of Central Asia[16] Analysis of skeletal remains from sites attributed to the Xiongnu provides an identification of dolichocephalic Mongoloid, which is ethnically distinct from the neighbouring populations in present-day Mongolia.[17]

According to a different genetic research on 75 individuals from various parts of Turkey, Mergen et al. revealed that the "genetic structure of the mtDNAs in the Turkish population bears some similarities to Turkic Central Asian populations".[18]

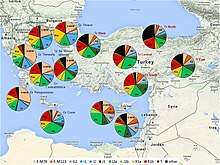

Haplogroup distributions

.png)

According to Cinnioğlu et al. (2004),[5] there are many Y-DNA haplogroups present in Turkey. Most haplogroups in Turkey are shared with their West Asian and Caucasian neighbours. The most common haplogroup in Turkey is J2 (24%), which is widespread among the Mediterranean, Caucasian and West Asian populations. Haplogroups that are common in Europe (R1b and I – 20%), South Asia (L, R2, H – 5.7%) and Africa (A, E3*, E3a – 1%) are also present. By contrast, Central Asian haplogroups are rarer (C, Q and O).

However, the figure may rise to 36% if K, R1a, R1b and L (which infrequently occur in Central Asia but are notable in many other Western Turkic groups) are also included. J2 is also frequently found in Central Asia, a notably high frequency (30.4%) being observed particularly among Uzbeks.[19]

Some of the percentages identified were:[5]

- J2=24% - J2 (M172)[5] Typical of North African, West Asian, Southern European, Caucasian, South Asian and Central Asian populations.[20]

- R1b=15.9%[5]

- G=10.9%[5]

- E3b-M35=10.7%[5] (E3b1-M78 and E3b3-M123 accounting for all E representatives in the sample, besides a single E3b2-M81 chromosome). E-M78 occurs commonly along a line from the Horn of Africa, via Egypt to the Balkans.[21] Haplogroup E-M123 is found in both Africa and Eurasia.

- J1=9%[5]

- R1a=6.9%[5]

- I=5.3%[5]

- K=4.5%[5]

- L=4.2%[5]

- N=3.8%[5]

- T=2.5%[5]

- Q=1.9%[5]

- C=1.3%[5]

- R2=0.96% [5]

Others markers than occurs in less than 1% are H, A, E3a , O , R1*.

Further research on Turkish Y-DNA groups

A study in Turkey by Gökçümen (2008)[22] took into account oral histories and historical records. They went to four settlements in Central Anatolia and did no a random selection from a group of university students, like in many other studies. Accordingly, here are the results:

1) In an Afshar village near Ankara where, according to oral tradition, the ancestors of the inhabitants came from Central Asia, the researchers found that 57% of the villagers had haplogroup L, 13% had haplogroup Q and 3% had haplogroup N. It was considered that examples of haplogroup L, which is most common in South Asia, might be a result of Central Asian migration even though the presence of haplogroup L in Central Asia itself was most likely a result of migration from South Asia. Therefore, Central Asian haplogroups potentially occurred in 73% of males in the village. Furthermore, 10% of the Afshars had haplogroups E3a and E3b, while only 13% had haplogroup J2a, the most common in Turkey.

2) The inhabitants of an older Turkish village that had little migration had about 25% of haplogroup N and 25% of J2a, with 3% of G and close to 30% of R1 variants (mostly R1b).

Whole genome sequencing

A study of Turkish genetics in 2014 used whole genome sequencing of individuals.[1] Led by Can Alkan at the University of Washington in Seattle, the study was published in the journal BMC Genomics. Its authors showed that the genetic variation of contemporary Turks clusters with South European populations, as expected, but it also shows signatures of relatively-recent contribution from ancestral East Asian populations. It estimated the weights for the migration events predicted to originate from the East Asian branch into Turkey at 21.7% (see Figure 2 by Alkan et al.).[1]

"(B) A population tree based on “Treemix” analysis. The populations included are as follows: Turkey (TUR); Tuscans in Italy (TSI); Iberian populations in Spain (IBS); British from England and Scotland (GBR); Finnish from Finland (FIN); Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry (CEU); Han Chinese in Beijing, China (CHB); Japanese in Tokyo, Japan (JPT); Han Chinese South (CHS); Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI); Luhya in Webuye, Kenya (LWK). Populations with high degree of admixture (Native American and African American populations) were not included to simplify the analysis. The Yoruban population was used to root the tree. In total four migration events were estimated. The weights for the migration events predicted to originate from the East Asian branch into current-day Turkey was 0.217 (21.7%), from the ancestral Eurasian branch into the Turkey-Tuscan clade was 0.048, from the African branch into Iberia was 0.026, from the Japanese branch into Finland was 0.079."[1]

Other studies

In 2001, Benedetto et al. revealed that Central Asian genetic contribution to the current Anatolian mtDNA gene pool was estimated as roughly 30% by comparing the populations of Mediterranean Europe and the Turkic-speaking people of Central Asia.[23] In 2004, Cinnioğlu et al. made a research of Y-DNA including the samples from eight regions of Turkey without classifying the ethnicity of the people, which indicated that high-resolution SNP analysis totally provides evidence of a detectable weak signal (<9%) of gene flow from Central Asia, which is an underestimate that summarizes only haplogroups C, Q and O.[5] It was later observed that the male contribution from Central Asia to Turkish population with reference to the Balkans was 13%. For all non-Turkic speaking populations, the Central Asian contribution was higher than in Turkey.[24] According to the study, "the contributions ranging between 13%–58% must be considered with a caution because they harbor uncertainties about the state of pre-nomadic invasion and further local movements." A 2006 study concluded that the Central Asian contribution to Anatolia for Y-DNA is 13%, mtDNA 22%, alu insertion (autosomal) 15%, autosomal 22%, with respect to Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uyghur, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan.[25].

In 2011 ,Aram Yardumian and Theodore G. Schurr published their study "Who Are the Anatolian Turks? A Reappraisal of the Anthropological Genetic Evidence." They revealed the impossibility of long-term and continuing genetic contacts between Anatolia and Siberia and confirmed the presence of significant mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome divergence between these regions, with minimal admixture. The research confirms also the lack of mass migration and suggested that it was irregular punctuated migration events that engendered large-scale shifts in language and culture among Anatolia's diverse autochthonous inhabitants.[9]

A study in 2015, however, found, "Previous genetic studies have generally used Turks as representatives of ancient Anatolians. Our results show that Turks are genetically shifted towards Central Asians, a pattern consistent with a history of mixture with populations from this region."[26]

According to a 2012 study of ethnic Turks, "Turkish population has a close genetic similarity to Middle Eastern and European populations and some degree of similarity to South Asian and Central Asian populations."[27] At K = 3 level, using individuals from the Middle East (Druze and Palestinian), Europe (French, Italian, Tuscan and Sardinian) to obtain a more representative database for Central Asia (Uygur, Hazara and Kyrgyz), clustering results indicated that the contributions were 45%, 40% and 15% for the Middle Eastern, European and Central Asian populations, respectively. For K = 4 level, results for paternal ancestry were 38% European, 35% Middle Eastern, 18% South Asian and 9% Central Asian. K= 7 results of paternal ancestry were 77% European, 12% South Asian, 4% Middle Eastern, 6% Central Asian. However, Hodoglugil et al. caution that results may indicate previous population movements (such as migration, admixture) or genetic drift.[27] The study indicated that the Turkish genetic structure is unique, and admixture of Turkish people reflects the population migration patterns.[27] Among all sampled groups, the Adygei population (Circassians) from the Caucasus was closest to the Turkish samples among sampled European (French, Italian), Middle Eastern (Druze, Palestinian), and Central (Kyrgyz, Hazara, Uygur), South (Pakistani), and East Asian (Mongolian, Han) populations.[27] A study involving mitochondrial analysis of a Byzantineera population, whose samples were gathered from excavations in the archaeological site of Sagalassos, found that the Byzantine population of Sagalassos may have left a genetic signature in the modern Turkish populations.[28] Modern samples from the nearby town of Ağlasun showed that lineages of East Eurasian descent assigned to macro-haplogroup M were found in the modern samples from Ağlasun. The haplogroup is significantly more frequent in Ağlasun (15%) than in Byzantine Sagalassos.[29]

Genetic history and Turkish identity

With the development of genetic researches of human history in the 21st century, criticism has arisen in Turkey by researchers traditionally concerned with the subject, such as anthropologists, archaeologists and historians. That kind of criticism is concerned with the formation of the biological construct of historical communities, which denies the 20th-century scholarly discourse by transforming the entities into purely-biological spheres. While the Central Asiatic origin of the Turkish people is a relatively new research topic in the history, which was developed in the late Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey, its clash with modern human genetics researches raises in a new light the questions: What was a "Turk(ic)" and who are the modern Turks?[30]

See also

- Demographics of Turkey

- History of the Turkish people

- Archaeogenetics of the Near East

- Genetic history of Europe

- Turkification

References and notes

- Alkan, Can; Kavak, Pinar; Somel, Mehmet; Gokcumen, Omer; Ugurlu, Serkan; Saygi, Ceren; Dal, Elif; Bugra, Kuyas; Güngör, Tunga; Sahinalp, S.; Özören, Nesrin; Bekpen, Cemalettin (2014). "Whole genome sequencing of Turkish genomes reveals functional private alleles and impact of genetic interactions with Europe, Asia and Africa". BMC Genomics. 15: 963. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-963. PMC 4236450. PMID 25376095.

- Irwin, Jodi A.; Ikramov, Abror; Saunier, Jessica; Bodner, Martin; Amory, Sylvain; Röck, Alexander; o'Callaghan, Jennifer; Nuritdinov, Abdurakhmon; Atakhodjaev, Sattar; Mukhamedov, Rustam; Parson, Walther; Parsons, Thomas J. (2010). "The mtDNA composition of Uzbekistan: A microcosm of Central Asian patterns". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 124 (3): 195–204. doi:10.1007/s00414-009-0406-z. PMID 20140442.

- See Figure in Di Cristofaro, Julie; Pennarun, Erwan; Mazières, Stéphane; Myres, Natalie M.; Lin, Alice A.; Temori, Shah Aga; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Witzel, Michael; King, Roy J.; Underhill, Peter A.; Villems, Richard; Chiaroni, Jacques (2013). "Afghan Hindu Kush: Where Eurasian Sub-Continent Gene Flows Converge". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e76748. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...876748D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076748. PMC 3799995. PMID 24204668.

- Arnaiz-Villena, A.; Karin, M.; Bendikuze, N.; Gomez-Casado, E.; Moscoso, J.; Silvera, C.; Oguz, F.S.; Sarper Diler, A.; De Pacho, A.; Allende, L.; Guillen, J.; Martinez Laso, J. (2001). "HLA alleles and haplotypes in the Turkish population: Relatedness to Kurds, Armenians and other Mediterraneans". Tissue Antigens. 57 (4): 308–17. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057004308.x. PMID 11380939.

- Cinnioglu, Cengiz; King, Roy; Kivisild, Toomas; Kalfoglu, Ersi; Atasoy, Sevil; Cavalleri, Gianpiero L.; Lillie, Anita S.; Roseman, Charles C.; Lin, Alice A.; Prince, Kristina; Oefner, Peter J.; Shen, Peidong; Semino, Ornella; Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca; Underhill, Peter A. (2004). "Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia". Human Genetics. 114 (2): 127–48. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1031-4. PMID 14586639.

- Rosser, Z; Zerjal, T; Hurles, M; Adojaan, M; Alavantic, D; Amorim, A; Amos, W; Armenteros, M; Arroyo, E; Barbujani, G (2000). "Y-Chromosomal Diversity in Europe is Clinal and Influenced Primarily by Geography, Rather than by Language". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (6): 1526–43. doi:10.1086/316890. PMC 1287948. PMID 11078479.

- Nasidze, I; Sarkisian, T; Kerimov, A; Stoneking, M (2003). "Testing hypotheses of language replacement in the Caucasus: Evidence from the Y-chromosome". Human Genetics. 112 (3): 255–61. doi:10.1007/s00439-002-0874-4. PMID 12596050.

- Wells, R. S.; Yuldasheva, N.; Ruzibakiev, R.; Underhill, P. A.; Evseeva, I.; Blue-Smith, J.; Jin, L.; Su, B.; Pitchappan, R.; Shanmugalakshmi, S.; Balakrishnan, K.; Read, M.; Pearson, N. M.; Zerjal, T.; Webster, M. T.; Zholoshvili, I.; Jamarjashvili, E.; Gambarov, S.; Nikbin, B.; Dostiev, A.; Aknazarov, O.; Zalloua, P.; Tsoy, I.; Kitaev, M.; Mirrakhimov, M.; Chariev, A.; Bodmer, W. F. (2001). "The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (18): 10244–9. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810244W. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098. JSTOR 3056514. PMC 56946. PMID 11526236.

- Schurr, Theodore G.; Yardumian, Aram (2011). "Who Are the Anatolian Turks?". Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia. 50 (1): 6–42. doi:10.2753/AAE1061-1959500101.

- Comas, D.; Schmid, H.; Braeuer, S.; Flaiz, C.; Busquets, A.; Calafell, F.; Bertranpetit, J.; Scheil, H.-G.; Huckenbeck, W.; Efremovska, L.; Schmidt, H. (2004). "Alu insertion polymorphisms in the Balkans and the origins of the Aromuns". Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (2): 120–7. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00080.x. PMID 15008791.

- Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg; Turdikulova, Shahlo (2015). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLoS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

- Arnaiz-Villena, A.; Gomez-Casado, E.; Martinez-Laso, J. (2002). "Population genetic relationships between Mediterranean populations determined by HLA allele distribution and a historic perspective". Tissue Antigens. 60 (2): 111–21. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.600201.x. PMID 12392505.

- Keyser-Tracqui, Christine; Crubézy, Eric; Ludes, Bertrand (2003). "Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Analysis of a 2,000-Year-Old Necropolis in the Egyin Gol Valley of Mongolia". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (2): 247–60. doi:10.1086/377005. PMC 1180365. PMID 12858290.

- Clisson, I; Keyser, C; Francfort, H. P.; Crubezy, E; Samashev, Z; Ludes, B (2002). "Genetic analysis of human remains from a double inhumation in a frozen kurgan in Kazakhstan (Berel site, Early 3rd Century BC)". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 116 (5): 304–8. doi:10.1007/s00414-002-0295-x. PMID 12376844.

- Kim, Kijeong; Brenner, Charles H.; Mair, Victor H.; Lee, Kwang-Ho; Kim, Jae-Hyun; Gelegdorj, Eregzen; Batbold, Natsag; Song, Yi-Chung; Yun, Hyeung-Won; Chang, Eun-Jeong; Lkhagvasuren, Gavaachimed; Bazarragchaa, Munkhtsetseg; Park, Ae-Ja; Lim, Inja; Hong, Yun-Pyo; Kim, Wonyong; Chung, Sang-In; Kim, Dae-Jin; Chung, Yoon-Hee; Kim, Sung-Su; Lee, Won-Bok; Kim, Kyung-Yong (2010). "A western Eurasian male is found in 2000-year-old elite Xiongnu cemetery in Northeast Mongolia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 142 (3): 429–40. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21242. PMID 20091844.

- Xue, Y.; Zerjal, T; Bao, W; Zhu, S; Shu, Q; Xu, J; Du, R; Fu, S; Li, P; Hurles, M. E.; Yang, H; Tyler-Smith, C (2005). "Male Demography in East Asia: A North-South Contrast in Human Population Expansion Times". Genetics. 172 (4): 2431–9. doi:10.1534/genetics.105.054270. PMC 1456369. PMID 16489223.

- Psarras, Sophia-Karin (2003). "Han and Xiongnu: A Reexamination of Cultural and Political Relations (I)". Monumenta Serica. 51: 55–236. doi:10.1080/02549948.2003.11731391. JSTOR 40727370.

- Mergen, Hatice; Öner, Reyhan; Öner, Cihan (2004). "Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in the Anatolian Peninsula (Turkey)" (PDF). Journal of Genetics. 83 (1): 39–47. doi:10.1007/bf02715828. PMID 15240908.

- Y-chromosome distributions among populations in Northwest China identify significant contribution from Central Asian pastoralists and lesser influence of western Eurasians Shou, Wei-Hua; Qiao, En-Fa; Wei, Chuan-Yu; Dong, Yong-Li; Tan, Si-Jie; Shi, Hong; Tang, Wen-Ru; Xiao, Chun-Jie (2010). "Y-chromosome distributions among populations in Northwest China identify significant contribution from Central Asian pastoralists and lesser influence of western Eurasians". Journal of Human Genetics. 55 (5): 314–322. doi:10.1038/jhg.2010.30. PMID 20414255.

- Shou, Wei-Hua; Qiao, En-Fa; Wei, Chuan-Yu; Dong, Yong-Li; Tan, Si-Jie; Shi, Hong; Tang, Wen-Ru; Xiao, Chun-Jie (2010). "Y-chromosome distributions among populations in Northwest China identify significant contribution from Central Asian pastoralists and lesser influence of western Eurasians". Journal of Human Genetics. 55 (5): 314–22. doi:10.1038/jhg.2010.30. PMID 20414255.

- Cruciani, Fulvio; La Fratta, Roberta; Torroni, Antonio; Underhill, Peter A.; Scozzari, Rosaria (2006). "Molecular dissection of the Y chromosome haplogroup E-M78 (E3b1a): A posteriori evaluation of a microsatellite-network-based approach through six new biallelic markers". Human Mutation. 27 (8): 831–2. doi:10.1002/humu.9445. PMID 16835895.

- Gokcumen, Omer (2008). Ethnohistorical and genetic survey of four Central Anatolian settlements (Thesis). pp. 1–189. OCLC 857236647.

- Di Benedetto, G; Ergüven, A; Stenico, M; Castrì, L; Bertorelle, G; Togan, I; Barbujani, G (2001). "DNA diversity and population admixture in Anatolia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 115 (2): 144–56. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.515.6508. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1064. PMID 11385601.

- Caner Berkman, Ceren; Togan, İnci (2009). "The Asian contribution to the Turkish population with respect to the Balkans: Y-chromosome perspective". Discrete Applied Mathematics. 157 (10): 2341–8. doi:10.1016/j.dam.2008.06.037.

- Berkman, Ceren (September 2006). Comparative Analyses for the Central Asian Contribution to Anatolian Gene Pool with Reference to Balkans (PDF) (PhD Thesis). Middle East Technical University. p. 98.

- Haber, Marc; Mezzavilla, Massimo; Xue, Yali; Comas, David; Gasparini, Paolo; Zalloua, Pierre; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2015). "Genetic evidence for an origin of the Armenians from Bronze Age mixing of multiple populations" (PDF). doi:10.1101/015396. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hodoğlugil, Uğur; Mahley, Robert W. (2012). "Turkish Population Structure and Genetic Ancestry Reveal Relatedness among Eurasian Populations". Annals of Human Genetics. 76 (2): 128–141. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x. PMC 4904778. PMID 22332727.

- Ottoni, C.; Ricaut, F. O. X.; Vanderheyden, N.; Brucato, N.; Waelkens, M.; Decorte, R. (2011). "Mitochondrial analysis of a Byzantine population reveals the differential impact of multiple historical events in South Anatolia". European Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (5): 571–576. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.230. PMC 3083616. PMID 21224890.

- Comparing maternal genetic variation across two millennia reveals the demographic history of an ancient human population in southwest Turkey Ottoni, Claudio; Rasteiro, Rita; Willet, Rinse; Claeys, Johan; Talloen, Peter; Van De Vijver, Katrien; Chikhi, Lounès; Poblome, Jeroen; Decorte, Ronny (2016). "Comparing maternal genetic variation across two millennia reveals the demographic history of an ancient human population in southwest Turkey". Royal Society Open Science. 3 (2): 150250. Bibcode:2016RSOS....350250O. doi:10.1098/rsos.150250. PMC 4785964. PMID 26998313.

- Celine Wawruschka, Genetic History and Identity: The Case of Turkey. Medieval worlds, No. 4, 2016, Institute for Medieval Research, Austrian Academy of Sciences, pp. 123-161.