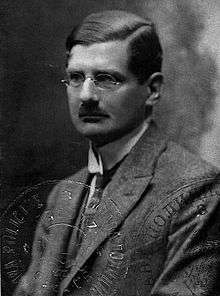

Ivo Pilar

Ivo Pilar (19 June 1874 – 3 September 1933) was a Croatian historian, politician and lawyer. His book The South Slav Question is a work on the South Slav geopolitical issues.

Ivo Pilar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 19 June 1874 |

| Died | 3 September 1933 (aged 59) |

| Resting place | Mirogoj cemetery, Zagreb, Croatia |

| Nationality | Croat |

| Alma mater | University of ViennaParis Law Faculty |

| Known for | Father of Croatian geopolitics;founder of the Croat People's Union |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | History, geopolitics, law |

Early career

Pilar was born in Zagreb, where he graduated from high school. He completed the studies in law in Vienna and attended lectures at the prestigious Ecole de Droit in Paris. He was one of the ideologues of the Croatian modernism and belonged to the group of the Croatian writers led by Silvije Strahimir Kranjčević after 1900.

He went from Paris back to Vienna, where he worked as a secretary in an ironworks corporation. Then he left for Sarajevo, where he was the secretary of the National Bank. He published essays and articles in Kranjčević's Nada and literary magazines in Zagreb, where he was employed at the Royal Court Table. In 1905 he went to Tuzla and opened his own legal practice. He stayed in Tuzla till 1920 and developed strong legal and Croatian patriotic activities. As he studied the conditions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, especially the position of the Croatian people, he actively engaged in politics, believing that Croats should be more forceful in defending their interests in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

He published the brochure Josip Štadler and the Croat People's Union (Sarajevo, 1908), which was opposed by the clergy and provoked a political rift between him and the Archbishop of Vrhbosna. In his brochure, Pilar concluded that the Catholic faith had undoubtedly an exceptional role in preserving the national identity of Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but he believed there were certain differences between the interests of the people and the Church as an organisation. In 1910 he founded the Croat People's Union, trying to politically awaken impassive Croatian Catholics and prepare them for the incoming portentous events. When World War I started, he was still in Tuzla.

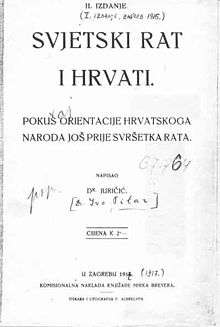

While many Croats eagerly awaited the dissolution of the hated Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Pilar warned that it was the only guarantee for a Croatian identity and that the country had to be reformed, but not destroyed. He published the essay World War and the Croats. An Attempt to Orient the Croatian People Even Before the War Ends in Zagreb in 1915, under the pseudonym dr. Jurčić. He was convinced that the Croatian political elite was lost in the contemporary events and that it was letting the Serbs take the initiative, instead of clearly formulating the goals and the program of the fight of the Croatian people in the world war. The essay was recognized by well-informed readership, so there was a second edition in 1917.

The developments in the Transleithanian part of the Monarchy were going against Pilar's wishes and beliefs, so he published a booklet of 32 pages in Sarajevo in 1918. It was called Political Geography of the Croatian Lands. A Geopolitical Study and it was the founding stone of Croatian geopolitics. Pilar was aware of its historical significance, since he said: We do not have any knowledge of any work on political geography of this kind in Croatian literature. (...) Therefore, this essay is the first of its kind in this area of our literature. In the essay, Pilar pointed out that the Croatian lands since 1908, i.e. since the Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, were incorporated in a single strong state, which guaranteed Croatian survival and where "today's Croatian lands flourish like never before".

The South Slav Question

Both essays were just a preparation for Pilar's magnum opus, best known under the title The South Slav Question. Pilar wrote it under the pseudonym of L. v. Südland. The full original title of the work in German language was: L. v. Südland, Die südslawische Frage und der Weltkrieg. Übersichtliche Darstellung des Gesamt–Problems (The South Slav Question and the World War. The Presentation of the Entire Problem). It was published in Vienna in 1918.

The second edition (also published in Vienna), as stated by Pucek (see below) in his introduction to the Croatian translation, was heavily censored, since such honest but formally mild criticism of the Austrian policy in the Croatian lands in the 19th century was not allowed by the Austrian government of the time. Pilar wrote the book in German because he intended it for the German linguistic area, especially the Austrian readers, but also the military and political circles of the embattled Monarchy.

In The South Slav Question Pilar placed great emphasis on racial determinism arguing that Croats had been defined by the so-called "Nordic-Aryan" racial and cultural heritage, while Serbs had "interbred" with the "Balkan-Romanic Vlachs." [1]

Book's reception

The interest for the book was below expectations, however. Still, for prevention's sake, as Pucek said, it was being confiscated. The Croatian politicians and intellectuals showed even less interest, since they were intent on the future union with the Serbs. At first, the book could not promote the mission of its author.

But this work in the area of South Slav issues was immediately recognized by Serbs and other promoters of a South Slavic Union, since the book warned Croats not to enter into states that would cause their ruin. They were buying its copies in Vienna and other cities of the Monarchy to destroy them. For this reason, it became a bibliographic rarity soon after its publication.

Croatian translation

When the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was created, any book's new edition became a problem. The first two parts of Pucek's Croatian translation were published in the youth magazine Hrvatska mladica, edited by Mile Starčević and Rikard Flogel, in 1928, but as the translator said, "the dictatorship of 6 January terminated Hrvatska mladica and this translation".

The third German edition of the book was printed in Zagreb in 1944, with all the faults of the censored second edition. It was finally translated to Croatian in 1943, a year before the third German edition, also with all the mentioned faults. It was translated, arranged and commented by the industrious South Slav expert Fedor Pucek and published by Matica hrvatska. Two years later, in 1945, Pucek was summarily executed by the communist regime. The second Croatian edition (1990) is just a reprint of the first.

Quotations

Hrvatima oteše današnju zapadnu Srbiju, nekadašnju Duklju, a jedna od glavnih sila koja je dovela do današnjeg rata (Prvi svjetski rat - S.T.), jest zagriženo nastojanje Srba, da Hrvatima konačno otmu i Bosnu i Hercegovinu

[The Serbs] took from the Croats modern-day western Serbia, that is ancient Doclea, and one the main forces that brought to today's war [First World War] , is the continuous seeking of the Serbs, to finally snatch away both Bosnia and Herzegovina too from the Croats.

Later years and death

Pilar moved to Zagreb in 1920. He was not actively engaged in politics any more. While working as a lawyer, he continued writing. In 1921, he was tried together with Milan Šufflay and other members of the Party of Rights in a fake political trial for high treason, for their alleged contacts with the Croatian Committee, a Croatian nationalist organization that was based in Hungary at the time.[2] He was brought to court, and despite the lack of evidence of wrongdoing, Pilar was given a two-month prison sentence and a one year of probation.[2]

He published expert and scientific works about philosophy and history (e.g. about the Bogumils). In 1933, he published the essay Serbia Again and Again in German, under the pseudonym of Florian Lichttrager, since he feared for his life.

Soon after that essay was published, Pilar was found killed in his apartment. The press in Belgrade claimed it was a suicide, but the open window of his apartment and the fact that Pilar never owned a weapon make his death suspicious. Even today, there are two theories about his death: the first, that Pilar was so depressed by the Yugoslav dictatorship that he killed himself; the second, that he was killed by Serbian secret agents like other Croatian patriots such as Milan Šufflay in 1931.

Pilar is buried in Mirogoj Cemetery.[3]

The Institute for Social Sciences in Zagreb was named after him in 1997.[4]

Works

- Nadbiskup Štadler i Hrvatska narodna zajednica (Archbishop Štadler and the Croatian National Community), Sarajevo, 1908

- Svjetski rat i Hrvati. Pokus orijentacije hrvatskoga naroda još prije svršetka rata (World War and the Croats. An Attempt to Orient the Croatian People Even Before the War Ends), Zagreb, 1915 (as dr. Jurčić)

- Politički zemljopis hrvatskih zemalja. Geopolitička studija (Political Geography of the Croatian Lands. A Geopolitical Study), Sarajevo, 1918

- Die südslavische Frage und der Weltkrieg. Übersichtliche Darstellung des Gesamt–Problems (The South Slav Question and the World War. The Presentation of the Entire Problem), Vienna, 1918 (as L. v. Südland); Croatian translation in 1943 and 1990 (reprint).

- Immer wieder Serbien (Serbia Again and Again), Zagreb, 1933 (as Florian Lichtträger); Croatian translation in 1994.

References

- Bartulin, Nevenko. The Racial Idea in the Independent State of Croatia. Brill, 2013, p.57

- Janjatović, Bosiljka (2002). "Dr. Ivo Pilar pred Sudbenim stolom u Zagrebu 1921. godine" [Dr. Ivo Pilar on Trial at the Zagreb's District Court in 1921]. Prinosi za proučavanje života i djela dra Ive Pilara (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: Institute of Social Sciences Ivo Pilar. 2: 121–139. ISSN 1333-4387.

- Ivo Pilar at Gradska Groblja Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "Povijest Instituta Ivo Pilar" (in Croatian). Retrieved 2019-04-04.

Sources

- Ivo Pilar Institute of Social Sciences

- (in Croatian) Prinosi za proučavanje života i djela dra. Ive Pilara

- (in Croatian) Umjesto vijenca Ivi Pilaru by Dubravko Jelčić