Nowruz

Nowruz (Persian: نوروز, pronounced [nowˈɾuːz]; lit. ' "new day"') is the Iranian New Year,[19][20] also known as the Persian New Year,[21][22] which is celebrated worldwide by various ethno-linguistic groups.

| Nowruz نوروز | |

|---|---|

Top to bottom:

| |

| Observed by |

|

| Type | National, ethnic, international |

| Significance | New Year holiday |

| Date | March 19, 20, 21 |

| Frequency | annual |

| Norooz, Nawrouz, Newroz, Novruz, Nowrouz, Nawrouz, Nauryz, Nooruz, Nowruz, Navruz, Nevruz, Nowruz, Navruz | |

|---|---|

| Country | Iran, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, India, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan |

| Reference | [UNESCO.org/culture/ich/en/RL/01161 1161] |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2016 (4th session) |

Nowruz has Iranian and Zoroastrian origins; however, it has been celebrated by diverse communities for over 7,000 years in Western Asia, Central Asia, the Caucasus, the Black Sea Basin, the Balkans, and South Asia.[23][24][25][26] It is a secular holiday for most celebrants that is enjoyed by people of several different faiths, but remains a holy day for Zoroastrians,[27] Bahais,[28] and some Muslim communities.[29][30]

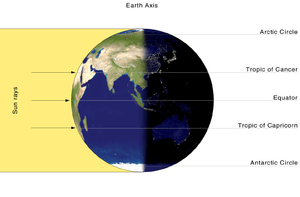

Nowruz is the day of the vernal equinox, and marks the beginning of spring in the Northern Hemisphere. It marks the first day of the first month (Farvardin) of the Iranian calendars.[31] It usually occurs on March 21 or the previous or following day, depending on where it is observed. The moment the Sun crosses the celestial equator and equalizes night and day is calculated exactly every year, and families gather together to observe the rituals.

While Nowruz has been celebrated since the reform of the Iranian Calendar in the 11th century CE to mark the new year, the United Nations officially recognized the "International Day of Nowruz" with the adoption of UN resolution 64/253 in 2010.[32]

Nowruz

The first day of the Iranian calendar falls on the March equinox, the first day of spring, around March 21. In the 11th century CE the Iranian calendar was reformed in order to fix the beginning of the calendar year, i.e. Nowruz, at the vernal equinox. Accordingly, the definition of Nowruz given by the Iranian scientist Tusi was the following: "the first day of the official New Year [Nowruz] was always the day on which the sun entered Aries before noon."[33] Nowruz is the first day of Farvardin, the first month of the Iranian solar calendar.

The word Nowruz is a combination of Persian words نو now—meaning "new"—and روز ruz—meaning "day". Pronunciation varies among Persian dialects, with Eastern dialects using the pronunciation [nawˈɾoːz] (as in Dari and Classical Persian, whereas in Tajik, it is written as "Наврӯз" Navröz), western dialects [nowˈɾuːz], and Tehranis [noːˈɾuːz]. A variety of spelling variations for the word nowruz exist in English-language usage, including novruz, nowruz, nauruz and newroz.[34][35][36]

Timing accuracy

Nowruz's timing in Iran is based on Solar Hijri algorithmic calendar, which is based on precise astronomical observations, and moreover use of sophisticated intercalation system, which makes it more accurate than its European counterpart, the Gregorian calendar.[37]

Each 2820 year great grand cycle contains 2137 normal years of 365 days and 683 leap years of 366 days, with the average year length over the great grand cycle of 365.24219852. This average is just 0.00000026 (2.6×10−7) of a day shorter than Newcomb's value for the mean tropical year of 365.24219878 days, but differs considerably more from the mean vernal equinox year of 365.242362 days, which means that the new year, intended to fall on the vernal equinox, would drift by half a day over the course of a cycle.[37]

Charshanbe Suri

Charshanbe Suri (Persian: چهارشنبهسوری, romanized: čahâr-šanbeh sūrī (lit. "Festive Wednesday") is a prelude to the New Year.[38] In Iran, it is celebrated on the eve of the last Wednesday before Nowruz. It is usually celebrated in the evening by performing rituals such as jumping over bonfires and lighting off firecrackers and fireworks.[39][40]

In Azerbaijan, where the preparation for Novruz usually begins a month earlier, the festival is held every Tuesday during four weeks before the holiday of Novruz. Each Tuesday, people celebrate the day of one of the four elements – water, fire, earth and wind.[41] On the holiday eve, the graves of relatives are visited and tended.[42]

Iranians sing the poetic line "my yellow is yours, your red is mine", which means:((my weakness to you and your strength to me)) (Persian: سرخی تو از من، زردی من از تو, romanized: zardi ye man az to, sorkhi ye to az man) to the fire during the festival, asking the fire to take away ill-health and problems and replace them with warmth, health, and energy. Trail mix and berries are also served during the celebration.

Spoon banging (قاشق زنی) is a tradition observed on the eve of Charshanbe Suri, similar to the Halloween custom of trick-or-treating. In Iran, people wear disguises and go door-to-door banging spoons against plates or bowls and receive packaged snacks. In Azerbaijan, children slip around to their neighbors' homes and apartments on the last Tuesday prior to Novruz, knock at the doors, and leave their caps or little basket on the thresholds, hiding nearby to wait for candies, pastries and nuts.[41]

The ritual of jumping over fire has continued in Armenia in the feast of Trndez, which is a feast of purification in the Armenian Apostolic Church and the Armenian Catholic Church, celebrated forty days after Jesus's birth.[43]

Sizdah bedar

In Iran, the Nowruz holidays last thirteen days. On the thirteenth day of the New Year, Iranians leave their houses to enjoy nature and picnic outdoors, as part of the Sizdebedar ceremony. The greenery grown for the Haft-sin setting is thrown away, particularly into a running water. It is also customary for young single people, especially young girls, to tie the leaves of the greenery before discarding it, expressing a wish to find a partner. Another custom associated with Sizdah Bedar is the playing of jokes and pranks, similar to April Fools' Day[44]

History and origin

Ancient roots

There exist various foundation myths for Nowruz in Iranian mythology.

The Shahnameh credits the foundation of Nowruz to the mythical Iranian King Jamshid, who saves mankind from a winter destined to kill every living creature.[45] To defeat the killer winter, Jamshid constructed a throne studded with gems. He had demons raise him above the earth into the heavens; there he sat, shining like the Sun. The world's creatures gathered and scattered jewels around him and proclaimed that this was the New Day (Now Ruz). This was the first day of Farvardin, which is the first month of the Iranian calendar.[46]

Although it is not clear whether Proto-Indo-Iranians celebrated a feast as the first day of the calendar, there are indications that Iranians may have observed the beginning of both autumn and spring, respectively related to the harvest and the sowing of seeds, for the celebration of the New Year.[47] Mary Boyce and Frantz Grenet explain the traditions for seasonal festivals and comment: "It is possible that the splendor of the Babylonian festivities at this season led the Iranians to develop their own spring festival into an established New Year feast, with the name Navasarda "New Year" (a name which, though first attested through Middle Persian derivatives, is attributed to the Achaemenian period)." Since the communal observations of the ancient Iranians appear in general to have been seasonal ones and related to agriculture, "it is probable that they traditionally held festivals in both autumn and spring, to mark the major turning points of the natural year."[47]

Nowruz is partly rooted in the tradition of Iranian religions, such as Mithraism and Zoroastrianism. In Mithraism, festivals had a deep linkage with the Sun's light. The Iranian festivals such as Mehrgan (autumnal equinox), Tirgan, and the eve of Chelle ye Zemestan (winter solstice) also had an origin in the Sun god (Surya). Among other ideas, Zoroastrianism is the first monotheistic religion that emphasizes broad concepts such as the corresponding work of good and evil in the world, and the connection of humans to nature. Zoroastrian practices were dominant for much of the history of ancient Iran. In Zoroastrianism, the seven most important Zoroastrian festivals are the six Gahambar festivals and Nowruz, which occurs at the spring equinox. According to Mary Boyce,[48] "It seems a reasonable surmise that Nowruz, the holiest of them all, with deep doctrinal significance, was founded by Zoroaster himself"; although there is no clear date of origin.[49] Between sunset on the day of the sixth Gahambar and sunrise of Nowruz, Hamaspathmaedaya (later known, in its extended form, as Frawardinegan; and today is known as Farvardigan) was celebrated. This and the Gahambars are the only festivals named in the surviving text of the Avesta.

The 10th-century scholar Biruni, in his work Kitab al-Tafhim li Awa'il Sina'at al-Tanjim, provides a description of the calendars of various nations. Besides the Iranian calendar, various festivals of Greeks, Jews, Arabs, Sabians, and other nations are mentioned in the book. In the section on the Iranian calendar, he mentions Nowruz, Sadeh, Tirgan, Mehrgan, the six Gahambars, Farvardigan, Bahmanja, Esfand Armaz and several other festivals. According to him, "It is the belief of the Iranians that Nowruz marks the first day when the universe started its motion."[50] The Persian historian Gardizi, in his work titled Zayn al-Akhbār, under the section of the Zoroastrians festivals, mentions Nowruz (among other festivals) and specifically points out that Zoroaster highly emphasized the celebration of Nowruz and Mehrgan.[51][52]

Achaemenid period

Although the word Nowruz is not recorded in Achaemenid inscriptions,[53] there is a detailed account by Xenophon of a Nowruz celebration taking place in Persepolis and the continuity of this festival in the Achaemenid tradition.[54] Nowruz was an important day during the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BCE). Kings of the different Achaemenid nations would bring gifts to the King of Kings. The significance of the ceremony was such that King Cambyses II's appointment as the king of Babylon was legitimized only after his participation in the referred annual Achaemenid festival.[55]

It has been suggested that the famous Persepolis complex, or at least the palace of Apadana and the Hundred Columns Hall, were built for the specific purpose of celebrating a feast related to Nowruz.

In 539 BCE, the Jews came under Iranian rule, thus exposing both groups to each other's customs. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, the story of Purim as told in the Book of Esther is adapted from an Iranian novella about the shrewdness of harem queens, suggesting that Purim may be an adoption of Iranian New Year.[56] A specific novella is not identified and Encyclopædia Britannica itself notes that "no Jewish texts of this genre from the Persian period are extant, so these new elements can be recognized only inferentially". Purim is celebrated within a few weeks of Nowruz as the date of Purim is based on a lunar calendar, while Nowruz occurs at the spring equinox. It is possible that the Jews and Iranians of the time may have shared or adopted similar customs for these holidays.[57]

Arsacid and Sassanid periods

Nowruz was the holiday of Arsacid dynastic empires who ruled Iran (248 BCE–224 CE) and the other areas ruled by the Arsacid dynasties outside of Parthia (such as the Arsacid dynasties of Armenia and Iberia). There are specific references to the celebration of Nowruz during the reign of Vologases I (51–78 CE), but these include no details.[53] Before Sassanids established their power in Western Asia around 300 CE, Parthians celebrated Nowruz in autumn, and the first of Farvardin began at the autumn equinox. During the reign of the Parthian dynasty, the spring festival was Mehrgan, a Zoroastrian and Iranian festival celebrated in honor of Mithra.[58]

Extensive records on the celebration of Nowruz appear following the accession of Ardashir I, the founder of the Sasanian Empire (224–651 CE). Under the Sassanid emperors, Nowruz was celebrated as the most important day of the year. Most royal traditions of Nowruz, such as royal audiences with the public, cash gifts, and the pardoning of prisoners, were established during the Sassanid era and persisted unchanged until modern times.

After the Muslim conquest

Nowruz, along with the mid-winter celebration Sadeh, survived the Muslim conquest of Persia of 650 CE. Other celebrations such as the Gahambars and Mehrgan were eventually side-lined or only observed by Zoroastrians. Nowruz became the main royal holiday during the Abbasid period. Much like their predecessors in the Sasanian period, Dehqans would offer gifts to the caliphs and local rulers at the Nowruz and Mehragan festivals.[59]

Following the demise of the caliphate and the subsequent re-emergence of Iranian dynasties such as the Samanids and Buyids, Nowruz became an even more important event. The Buyids revived the ancient traditions of Sassanian times and restored many smaller celebrations that had been eliminated by the caliphate. The Iranian Buyid ruler 'Adud al-Dawla (r. 949–983) customarily welcomed Nowruz in a majestic hall, decked with gold and silver plates and vases full of fruit and colorful flowers.[60] The King would sit on the royal throne, and the court astronomer would come forward, kiss the ground, and congratulate him on the arrival of the New Year.[60] The king would then summon musicians and singers, and invited his friends to gather and enjoy a great festive occasion.[60]

Later Turkic and Mongol invaders did not attempt to abolish Nowruz.

Contemporary era

Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Iran was the only country that officially observed the ceremonies of Nowruz. When the Caucasian and Central Asian countries gained independence from the Soviets, they also declared Nowruz as a national holiday.

Nowruz was added to the UNESCO List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010.[61][62][63][64][65] To commemorate the UN recognition, Iran unveiled a commemorative postage stamp during the first International Nowruz Celebrations in Tehran on Saturday, March 27, 2010.[66]

Holiday customs

House cleaning and shopping

House cleaning, or shaking the house (Persian: خانه تکانی, romanized: xāne tekāni) is commonly done before the arrival of Nowruz. People start preparing for Nowruz with a major spring cleaning of their homes and by buying new clothes to wear for the New Year, as well as the purchase of flowers. The hyacinth and the tulip are popular and conspicuous.[67]

Visiting family and friends

During the Nowruz holidays, people are expected to make short visits to the homes of family, friends and neighbors. Typically, young people will visit their elders first, and the elders return their visit later. Visitors are offered tea and pastries, cookies, fresh and dried fruits and mixed nuts or other snacks. Many Iranians throw large Nowruz parties in as a way of dealing with the long distances between groups of friends and family.[68]

Haft-sin

Typically, before the arrival of Nowruz, family members gather around the Haft-sin table and await the exact moment of the March equinox to celebrate the New Year.[69][70] Traditionally, the Haft-sin (Persian: هفتسین, seven things beginning with the letter sin (س)) are:

- Sabze (Persian: سبزه) – wheat, barley, mung bean, or lentil sprouts grown in a dish.

- Samanu (Persian: سمنو) – sweet pudding made from wheat germ

- Persian olive (Persian: سنجد, romanized: senjed)

- Vinegar (Persian: سرکه, romanized: serke)

- Apple (Persian: سیب, romanized: sib)

- Garlic (Persian: سیر, romanized: sir)

- Sumac (Persian: سماق, romanized: somāq)

The Haft-sin table may also include a mirror, candles, painted eggs, a bowl of water, goldfish, coins, hyacinth, and traditional confectioneries. A "book of wisdom" such as the Quran, Bible, Avesta, the Šāhnāme of Ferdowsi, or the divān of Hafez may also be included.[69] Haft-sin's origins are not clear. The practice is believed to have been popularized over the past 100 years.[71]

Haft Mēwa

In Afghanistan, people prepare Haft Mēwa (Dari: هفت میوه, English: seven fruits) for Nauruz, a mixture of seven different dried fruits and nuts (such as raisins, Persian olives, pistachios, hazelnuts, prunes, walnut, and almonds) served in syrup. [72]

Khoncha

Khoncha (Azerbaijani: Xonça) is the traditional display of Novruz in the Republic of Azerbaijan. It consists of a big silver or copper tray, with a tray of green, sprouting wheat (samani) in the middle and a dyed egg for each member of the family arranged around it. The table should be with at least seven dishes.[41]

Amu Nowruz and Haji Firuz

In Iran, the traditional heralds of the festival of Nowruz are Amu Nowruz and Haji Firuz, who appear in the streets to celebrate the New Year.

Amu Nowruz brings children gifts, much like his counterpart Santa Claus.[73] He is the husband of Nane Sarma, with whom he shares a traditional love story in which they can meet each other only once a year.[74][75] He is depicted as an elderly silver-haired man with a long beard carrying a walking stick, wearing a felt hat, a long cloak of blue canvas, a sash, giveh, and linen trousers.[76]

Haji Firuz, a character with his face and hands covered in soot, clad in bright red clothes and a felt hat, is the companion of Amu Nowruz. He dances through the streets while singing and playing the tambourine. In the traditional songs, he introduces himself as a serf trying to cheer people whom he refers to as his lords.[77]

Kampirak

In the folklore of Afghanistan, Kampirak and his retinue pass village by village distributing gathered charities among people. He is an old bearded man wearing colorful clothes with a long hat and rosary who symbolizes beneficence and the power of nature yielding the forces of winter. The tradition is observed in central provinces, specially Bamyan and Daykundi.[78]

Poetic Compositions

In his composition describing his encounter with Imam Shah Khalil Allah on the day of Nawruz, Sayyid Fath ‘Ali Shah Shamsi uses the physical meeting to explain a spiritual experience. He describes the Imam as a “lord of the resurrection,” which is a symbolic description for Nawruz being associated with the revival of souls at the end of time. The entirety of his composition includes immense symbolic references, such as being dyed in the master’s eternal colour, his life-breath blossoming like a flower, and caskets being filled with pearls. This description of caskets being filled with pearls is a symbol of “supreme knowledge in the Indian poetic imagination.” Sayyid Fath ‘Ali Shah Shamsi writes about his desire to see the lord, which is fulfilled when He appears (eternally) in the form of pure light.[79]

Locality

The festival of Nowruz is celebrated by many groups of people in the Black Sea basin, the Balkans, the Caucasus, Western Asia, central and southern Asia, and by Iranians worldwide.[80]

Places where Nowruz is a public holiday include:

The Parliament of Canada, on March 30, 2009, by unanimous consent, passed a bill to add Nowruz to the national calendar of Canada.[93][94]

Nowruz is celebrated by Kurdish people in Iraq[7][95] and Turkey,[96] as well as by the Iranis, Shias and Parsis in the Indian subcontinent and diaspora.

Nowruz is also celebrated by Iranian communities the Americas and in Europe, including Los Angeles, Phoenix, Toronto, Cologne and London.[97] In Phoenix, Arizona, Nowruz is celebrated at the Persian New Year Festival.[98] But because Los Angeles is prone to devastating fires, there are very strict fire codes in the city. Usually, Iranians living in Southern California go to the beaches to celebrate the event where it is permissible to build fires.[99] On March 15, 2010, the House of Representatives of the United States passed the Nowruz Resolution (H.Res. 267), by a 384–2 vote,[100] "Recognizing the cultural and historical significance of Nowruz, ... ."[101]

Afghanistan

Nowruz marks Afghanistan's New Year's Day with the Solar Hijri Calendar as their official calendar. In Afghanistan, the festival of Gul-i-Surkh (Dari: گل سرخ, English: red flower) is the principal festival for Nauruz. It is celebrated in Mazar-i-Sharif during the first 40 days of the year, when red tulips grow in the green plains and over the hills surrounding the city. People from all over the country travel to Mazar-i-Sharif to attend the Nauruz festivals. Buzkashi tournaments are held during the Gul-i-Surkh festival in Mazar-i-Sharif, Kabul and other northern Afghan cities.

Jahenda Bala (Dari: جهنده بالا English: raising) is celebrated on the first day of the New Year.[102] It is a religious ceremony performed at the Blue Mosque of Mazar-i-Sharif by raising a special banner resembling the Derafsh Kaviani royal standard. It is attended by high-ranking government officials such as the Vice-President, Ministers, and Provincial Governors and is the biggest recorded Nawroz gathering, with up to 200,000 people from all over Afghanistan attending.

In the festival of Dehqān (Dari: دهقان English: farmer), also celebrated on the first day of the New Year, farmers walk in the cities as a sign of encouragement for the agricultural production. In recent years, this activity only happens in Kabul and other major cities where the mayor and other government officials attend.

During the first two weeks of the New Year, the citizens of Kabul hold family picnics in Istalif, Charikar and other green places where redbuds grow.

During the Taliban regime of 1996–2001, Nauruz was banned as "an ancient pagan holiday centered on fire worship".[103]

Armenia

Since the extinction during the 19th century, Nowruz is not celebrated by Armenians and is not a public holiday in Armenia. However, it is celebrated in Armenia by tens of thousands of Iranian tourists who visit Armenia with relative ease.[104] The influx of tourists from Iran accelerated since around 2010–11.[105][106] In 2010 alone, around 27,600 Iranians spent Nowruz in capital Yerevan.[107]

In 2015, President Serzh Sargsyan sent a letter of congratulations to Kurds living in Armenia and to the Iranian political leadership on the occasion of Nowruz.[108]

Azerbaijan

In Azerbaijan, Novruz celebrations go on for several days and included festive public dancingfolk music, and sporting competitions. In rural areas, crop holidays are also marked.[109]

Communities of the Azeri diaspora also celebrate Nowruz in the US, Canada,[110] and Israel.[111]

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, Shia Muslims in Dhaka, Chittagong, Rajshahi and Khulna continue to celebrate it regularly. However, tradition goes back to historical East Bengal's link to the Mughal Empire; the empire celebrated the festival for 19 days with pomp and gaiety.[112][113] Shia Muslims in Bangladesh have been seen spraying water around their home and drinking that water to keep themselves protected from diseases. A congregation to seek divine blessing is also arranged. Members of the Nawab family of Dhaka used to celebrate it amid pomp and grounder. In the evening, they used to float thousands of candle lights in nearby ponds and water bodies. Bengali poet Kazi Nazrul Islam portrayed a vivid sketch of the festival highlighting its various aspects. In his poem, he described it as a platform of exposing a youth's physical and mental beauty to another opposite one for conquering his or her heart.[114]

Central Asia

Nawruz widely celebrated on a vast territory of Central Asia and ritual practice acquired its special features. [115]

China

Traditionally, Nowruz is celebrated mainly in China's Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region by the Uyghurs, Chinese Tajik, Salar, and Kazakh ethnicities.[4]

Georgia

Nowruz is not celebrated by Georgians, but it is widely celebrated by the country's large Azerbaijani minority (~7% of the total population)[116] as well as by Iranians living in Georgia.[116][117] Every year, large festivities are held in the capital Tbilisi, as well as in areas with a significant number of Azerbaijanis, such as the Kvemo Kartli, Kakheti, Shida Kartli, and Mtskheta-Mtianeti regions.[116] Georgian politicians have attended the festivities in the capital over the years, and have congratulated the Nowruz-observing ethnic groups and nationals in Georgia on the day of Nowruz.[118][119]

India

The Parsi community of India observe the new year using the Shahenshahi calendar which does not account for leap years, meaning this holiday has now moved by 200 days from its original day of the vernal equinox. In India the Parsi New Year is celebrated around 16-17 August.

Tradition of Nowruz in Northern India dates back to the Mughal Empire; the festival was celebrated for 19 days with pomp and gaiety in the realm.[112][113] However, it further goes back to the Parsi Zoroastrian community in Western India, who migrated to the Indian subcontinent from Persia during the Muslim conquest of Persia of 636–651 CE. In the Princely State of Hyderabad, Nowruz (Nauroz) was one of the four holidays where the Nizam would hold a public Darbar, along with the two official Islamic holidays and the sovereign's birthday.[120] Prior to Asaf Jahi rule in Hyderabad, the Qutb Shahi dynasty celebrated Nowruz with a ritual called Panjeri, and the festival was celebrated by all with great grandeur.[121] Kazi Nazrul Islam, during the Bengal renaissance, portrayed the festival with vivid sketch and poems, highlighting its various aspects.[114]

Iran

Nowruz is two-week celebration that marks the beginning of the New Year in Iran's official Solar Hejri calendar.[122][123] The celebration includes four public holidays from the first to the fourth day of Farvardin, the first month of the Iranian calendar, usually beginning on March 21.[124] On the Eve of Nowruz, the fire festival Chaharshanbe Suri is celebrated.[125]

Following the 1979 Revolution, some radical elements from the Islamic government attempted to suppress Nowruz,[126] considering it a pagan holiday and a distraction from Islamic holidays. Nowruz has been politicized, with political leaders making annual Nowruz speeches.[127]

Kurds

Newroz is largely considered as a potent symbol of Kurdish identity in Turkey, even if there are some Turks (including Turkmens) celebrating the festival. The Kurds of Turkey celebrate this feast between 18th till March 21. Kurds gather into fairgrounds mostly outside the cities to welcome spring. Women wear colored dresses and spangled head scarves and young men wave flags of green, yellow and red, the historic colors of Kurdish people. They hold this festival by lighting fire and dancing around it.[128] Newroz has seen many bans in Turkey and can only be celebrated legally since 1992 after the ban on the Kurdish language was lifted. But also afterwards Newroz celebrations could be banned and lead to confrontations with the Turkish authority. In Cizre, Nusyabin and Şırnak celebrations turned violent as Turkish police forces fired in the celebrating crowds.[129] Newroz celebrations are usually organized by Kurdish cultural associations and pro-Kurdish political parties. Thus, the Democratic Society Party was a leading force in the organisation of the 2006 Newroz events throughout Turkey. In recent years, the Newroz celebration gathers around 1 million participants in Diyarbakır, the biggest city of the Kurdish dominated Southeastern Turkey. As the Kurdish Newroz celebrations in Turkey often are theater for political messages, the events are frequently criticized for being political rallies rather than cultural celebrations.

Until 2005, the Kurdish population of Turkey could not celebrate their New Year openly.[130] "Thousands of people have been detained in Turkey, as the authorities take action against suspected supporters of the Kurdish rebel movement, the PKK.[131] The holiday is now official in Turkey after international pressure on the Turkish government to lift culture bans. Turkish government renamed the holiday Nevroz in 1995.[132] In the recent years, limitations on expressions of Kurdish national identity, including the usage of Kurdish in the public sphere, have been considerably relaxed.

On March 21, 2013, PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan called for a ceasefire through a message that was released in Diyarbakır during the Newroz celebrations.[133]

In Syria, the Kurds dress up in their national dress and celebrate the New Year.[134] According to Human Rights Watch, the Kurds have had to struggle to celebrate Newroz, and in the past the celebration has led to violent oppression, leading to several deaths and mass arrests.[135] The Syrian Arab Ba'athist government stated in 2004 that the Newroz celebrations will be tolerated as long as they do not become political demonstrations.[136] During the Newroz celebrations in 2008, three Kurds were shot dead by Syrian security forces.[137][138] In March 2010, an attack by Syrian police left 2 or 3 people killed, one of them a 15-year-old girl, and more than 50 people wounded.[139] The Rojava revolution of 2012 and the subsequent establishment of the de facto Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria saw Kurdish civil rights greatly expand, and Newroz is now celebrated freely in most Kurdish areas of Syria except for Efrin, where the ritual is no longer allowed since the 2018 occupation by Turkish-backed rebel groups.[140]

Kurds in the diaspora also celebrate the New Year; for example, Kurds in Australia celebrate Newroz, not only as the beginning of the new year, but also as the Kurdish National Day. The Kurds in Finland celebrate the new year as a way of demonstrating their support for the Kurdish cause.[141] Also in London, organizers estimated that 25,000 people celebrated Newroz during March 2006.[142]

Pakistan

In Pakistan, Nowruz is typically celebrated in parts of Gilgit-Baltistan,[143] Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, especially near the border with Afghanistan, and across Baluchistan, with a large celebration in the capital of Quetta.[144] Recently, the government of Iran has become involved in hosting celebrations in Islamabad to commemorate the holiday.[144] Like in India, the Parsi and Ismaili communities has also historically celebrated the holiday.[145]

Theology

Followers of the Zoroastrian faith include Nowruz in their religious calendar, as do followers of other faiths.[146] Shia literature refers to the merits of the day of Nowruz; the Day of Ghadir took place on Nowruz; and the fatwas of major Shia scholars[147] recommend fasting. Nowruz is also a holy day for Sufis, Bektashis, Ismailis, Alawites,[148] Alevis, Babis and adherents of the Bahá'í Faith.[149]

Bahá'í Faith

Naw-Rúz is one of nine holy days for adherents of the Bahá'í Faith worldwide. It is the first day of the Bahá'í calendar, occurring on the vernal equinox around March 21.[150] The Bahá'í calendar is composed of 19 months, each of 19 days,[151] and each of the months is named after an attribute of God; similarly each of the nineteen days in the month also are named after an attribute of God.[151] The first day and the first month were given the attribute of Bahá, an Arabic word meaning splendour or glory, and thus the first day of the year was the day of Bahá in the month of Bahá.[150][152] Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, explained that Naw-Rúz was associated with the Most Great Name of God,[150][152] and was instituted as a festival for those who observed the Nineteen day fast.[153][154]

The day is also used to symbolize the renewal of time in each religious dispensation.[155] `Abdu'l-Bahá, Bahá'u'lláh's son and successor, explained that significance of Naw-Rúz in terms of spring and the new life it brings.[150] He explained that the equinox is a symbol of the messengers of God and the message that they proclaim is like a spiritual springtime, and that Naw-Rúz is used to commemorate it.[156]

As with all Bahá'í holy days, there are few fixed rules for observing Naw-Rúz, and Bahá'ís all over the world celebrate it as a festive day, according to local custom.[150] Persian Bahá'ís still observe many of the Iranian customs associated with Nowruz such as the Haft-sin, but American Bahá'í communities, for example, may have a potluck dinner, along with prayers and readings from Bahá'í scripture.

Twelver and Ismaili Shia

Along with Ismailis,[157][158] Alawites and Alevis, the Twelver Shia also hold the day of Nowruz in high regard.

It has been said that Musa al-Kadhim, the seventh Twelver Shia imam, has explained Nowruz and said: "In Nowruz God made a covenant with His servants to worship Him and not to allow any partner for Him. To welcome His messengers and obey their rulings. This day is the first day that the fertile wind blow and the flowers on the earth appeared. The archangel Gabriel appeared to the Prophet, and it is the day that Abraham broke the idols. The day Prophet Muhammad held Ali on his shoulders to destroy the Quraishie's idols in the house of God, the Kaaba."[159]

The day upon which Nowruz falls has been recommended as a day of fasting for Twelver Shia Muslims by Shia scholars, including Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei, Ruhollah Khomeini[160] and Ali al-Sistani.[161] The day also assumes special significance for Shias as it has been said that it was on 16 March 632 AD that the first Shia Imam, Ali, assumed the office of caliphate. The Shia Imami Ismaili muslims around the globe celebrate the Nawruz as a religious festival. Special prayers and Majalis are arranged in Jamatkhanas. Special foods are cooked and people share best wishes and prayers with each other. In Gilgit Baltistan Nawruz is being celebrated officially.

See also

- New Year's Day

- Dumuzid

- Assyrian New Year

- Pohela Boishakh

- Sham el-Nessim

- Akitu

- Seharane

- Aroos-Gooleh

- Vernal Equinox Day, one of the two Kōreisai Japanese holidays

- Ostara

Notes

- Eternal combat between the bull representing the Moon, and the lion representing the Sun and spring.

References

- "The World Headquarters of the Bektashi Order – Tirana, Albania". komunitetibektashi.org. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- "Albania 2010 Bank Holidays". Bank-holidays.com. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Nowruz conveys message of secularism, says Gowher Rizvi". United News of Bangladesh. April 6, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- "Xinjiang Uygurs celebrate Nowruz festival to welcome spring". Xinhuanet. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- "Nowruz Declared as National Holiday in Georgia". civil.ge. March 21, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- "Nowruz observed in Indian subcontinent". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- "20 March 2012 United Nations Marking the Day of Nawroz". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Iraq). Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- "Celebrating Nowruz in Central Asia". fravahr.org. Archived from the original on May 23, 2007. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- "Farsnews". Fars News. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- "Россия празднует Навруз [Russia celebrates Nowruz]". Golos Rossii (in Russian). March 21, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- "Arabs, Kurds to Celebrate Nowruz as National Day". Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- For Kurds, a day of bonfires, legends, and independence. Dan Murphy. March 23, 2004.

- "Tajikistan 2010 Bank Holidays". Bank-holidays.com. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ANADOLU’DA NEVRUZ KUTLAMALARI ve EMİRDAĞ-KARACALAR ÖRNEĞİ Anadolu'da Nevruz Kutlamalari

- Emma Sinclair-Webb, Human Rights Watch, "Turkey, Closing ranks against accountability", Human Rights Watch, 2008. "The traditional Nowrouz/Nowrooz celebrations, mainly celebrated by the Kurdish population in the Kurdistan Region in Iraq, and other parts of Kurdistan in Turkey, Iran, Syria and Armenia and taking place around March 21"

- "General Information of Turkmenistan". sitara.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- Nowruz celebrations in the North Cyprus

- Nevruz kutlamaları Lefkoşa'da gerçekleştirildi.

- "Culture of Iran: No-Rooz, The Iranian New Year at Present Times". www.iranchamber.com. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

- Stausberg, Michael; Sohrab-Dinshaw Vevaina, Yuhan (2015). "The Iranian festivals: Nowruz and Mehregan". The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 494–495. ISBN 978-1118786277.

- "NOWRUZ". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

Nowruz, "New Day", is a traditional ancient festival which celebrates the starts of the Persian New Year.

- Melton, J. Gordon (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 620. ISBN 978-1598842067.

Nowruz, an ancient spring festival of Persian origin (and the Zoroastrian New Year's day)...

- "General Assembly Recognizes 21 March as International Day of Nowruz, Also Changes to 23–24 March Dialogue on Financing for Development – Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". UN. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Kenneth Katzman (2010). Iran: U. S. Concerns and Policy Responses. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 9781437918816. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- General Assembly Fifty-fifth session 94th plenary meeting Friday, 9 March 2001, 10 a.m. New York. United Nations General Assembly. March 9, 2001. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- J. Gordon Melton (September 13, 2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842067. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- Azoulay, Vincent (July 1, 1999). Xenophon and His World: Papers from a Conference Held in Liverpool in July 1999. ISBN 9783515083928. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- "Welcome to the Baha'i New Year, Naw-Ruz!". BahaiTeachings.org. March 21, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- Isgandarova, Nazila (September 3, 2018). Muslim Women, Domestic Violence, and Psychotherapy: Theological and Clinical Issues. Routledge. ISBN 9780429891557.

- "Navroz". the.Ismaili. March 21, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- "What Is Norooz? Greetings, History And Traditions To Celebrate The Persian New Year". International Business Times. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

- "International Day of Nowruz". United Nations. February 18, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- R. Abdollahy, Calendars ii. Islamic period, in Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. 4, London & New York, 1990.

- Random House dictionary (unabridged), 2006 (according to Dictionary.reference.com).

- Elien, Shadi, "Is the Persian New Year spelled Norouz, Nowruz, or Nauruz?", The Georgia Straight, March 17, 2010.

- "Nowruz as Parsi New Year" 16-8-2020

- "Iranian Calendar". aramis.obspm.fr. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- Lezgee, Hoda (March 20, 2015). "The Celebration of Spring in Iran".

Nevertheless, the most important curtain-raiser to Norouz is Chaharshanbe Soori which is a fire festival held on the eve of the last Wednesday of the calendar year. This festival is full of special customs and rituals, especially jumping over fire.

- "Call for Safe Yearend Celebration". Financial Tribune. March 12, 2017.

The ancient tradition has transformed over time from a simple bonfire to the use of firecrackers...

- "Light It Up! Iranians Celebrate Festival of Fire". NBC News. March 19, 2014.

- "International Day of Nowruz- 21 March". Azerembassy-kuwait.org. March 17, 2010. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Azerbaijani traditions". Everyculture.com. May 28, 1918. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- Marshall, Bonnie C.: Tashjian, Virginia A, The Flower of Paradise and Other Armenian Tales Libraries Unlimited 2007 p. xxii

- "April Fools' Day 2016: how did the tradition originate and what are the best pranks?". Emily Allen and Juliet Eysenck. Telegraph. 17 March 2016.

- Moazami, M. "The Legend of the Flood in Zoroastrian Tradition." Persica 18: 55–74, (2002) Document Details

- Firdawsī (2006). Shahnameh:a new translation by Dick Davis, Viking Adult, 2006. p. 7. ISBN 978-0670034857.

- A History of Zoroastrianism: Under the Achaemenians By Mary Boyce, Frantz Grenet. Brill, 1982 ISBN 90-04-06506-7, 978-90-04-06506-2, pp. 3–4

- Encyclopædia Iranica, "Festivals: Zoroastrian" Boyce, Mary Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Boyce, M. "Festivals. i. Zoroastrian". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- برگرفته از: "گنجينهي سخن"، تأليف دكتر ذبيح الله صفا، انتشارات اميركبير، 1370، جلد يكم، ص 292

- Gardīzī, Abu Saʿīd ʿAbd-al-Ḥayy b. Żaḥḥāk b. Maḥmūd in Encyclopedia Iranica by C. Edmund Bosworth Iranica on line

- Tārīkh-i Gardīzī / taʾlīf, Abū Saʻīd ʻAbd al-Ḥayy ibn Zahāk ibn Maḥmūd Gardīzī ; bih taṣḥīḥ va taḥshiyah va taʻlīq, ʻAbd al-Ḥayy Ḥabībī. Tihrān : Dunyā-yi Kitāb, 1363 [1984 or 1985]. excerpt from p. 520: مهرگان بزرگ باشد، و بعضی از مغان چنین گویند: که این فیروزی فریدون بر بیوراسپ، رام روز بودست از مهرماه، و زردشت که مغان او را به پیغمبری دارند، ایشان را فرموده است بزرگ داشتن این روز، و روز نوروز را.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad. "Nowruz in History". Archived from the original on April 11, 2004. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- Christopher Tuplin; Vincent Azoulay, Xenophon and His World: Papers from a Conference Held in Liverpool in July 1999, Published by Franz Steiner Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-515-08392-8, p. 148.

- Trotter, James M. (2001). Reading Hosea in Achaemenid Yehud. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-84127-197-2.

- The Judaic tradition " Jewish myth and legend " Sources and development " Myth and legend in the Persian period. "Encyclopædia Britannica". Retrieved March 21, 2009.

- Hastings, James; Selbie, John Alexander; Gray, Louis Herbert, eds. (1919). "Purim". Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. 10. p. 506.

- John R. Hinnells, "Mithraic studies: proceedings", Edition: illustrated, Published by Manchester University Press ND, 1975, ISBN 0-7190-0536-1, 978-0-7190-0536-7, p. 307

- DEHQĀN iranicaonline.org

- "A. Shapur Shahbazi, "Nowruz: In the Islamic period"". Iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- Novruz, Nowrouz, Nooruz, Navruz, Nauroz, Nevruz: Inscribed in 2009 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, UNESCO.

- Noruz and Iranian radifs registered on UNESCO list, Tehran Times, October 1, 2009, TehranTimes.com.

- International Nowruz Day 21 March un.org

- Persian music, Nowruz make it into UN heritage list, Press TV, October 1, 2009, PressTV.ir

- Nowruz became international, in Persian, BBC Persian, Wednesday, September 30, 2009, BBC.co.uk

- Iran issues stamp celebrating Int'l Day of Nowruz, PRESS TV, March 28, 2010

- "صفای ظاهر و باطن در رسم دیرین خانه تكانی". irna.

- "ديد و بازديد نوروزي، آييني نيكو و ديرينه پابرجا". IRNA.

- Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009). "Navruz". Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. pp. 524–525. ISBN 9781438126968.

- "Noruz, manifestation of culture of peace, friendship among societies". Tehran Times. April 7, 2018.

- "Nowruz: Persian New Year's Table Celebrates Spring Deliciously". NPR. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- "از هفت سین تا هفت میوه".

- "Haji Firooz & Amoo Norooz – The Persian Troubadour & Santa Claus". Persian Mirror. November 15, 2004. Archived from the original on February 25, 2010. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- Thus Speaks Mother Simorq, p. 151

- Iranica: Pir-e Zan

- Amu Nowruz Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Fazlollah Mohtadi, Shiraz University Centre for Children's Literature Studies

- Faces around the World: A Cultural Encyclopedia of the Human Face By Margo DeMello – Black Face, p. 28

- Arvin, Ayub. "نوروز و چالشهای سیاسی و مذهبی در افغانستان". London: BBC Persian. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- Virani, Shafique. "The Festival of Nawruz in the Ginans". The Ismailis: An Illustrated History.

- Rostami, Hoda (March 17, 2007). "Yek Jahan Noruz". Saman (Publication of Iranian National Tax Administration) (23).

- Lt. j.g. Keith Goodsell (March 7, 2011). "Key Afghan, US leadership plant trees for Farmer's Day". United States Central Command. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- "BBCPersian.com". BBC. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Azerbaijan 2010 Bank Holidays". Bank-holidays.com. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Nowruz Declared as National Holiday in Georgia". Civil.Ge. July 1, 2001. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Iran (Islamic Republic of) 2010 Bank Holidays". Bank-holidays.com. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Iraq 2010 Bank Holidays". Bank-holidays.com. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Norouz in Kyrgyzstan". Payvand.com. March 26, 2006. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Kyrgyzstan 2010 Bank Holidays". Bank-holidays.com. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Discover Bayan-Olgii".

- "Turkmen President Urges Youth To Read 'Rukhnama'". RFERL. March 20, 2006. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Turkmenistan 2010 Bank Holidays". Bank-holidays.com. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Uzbekistan 2010 Bank Holidays". Bank-holidays.com. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Canada parliament recognizes 'Nowruz Day'". Press TV. April 3, 2009. Archived from the original on January 11, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- "Bill c-342". House of Commons of Canada. Retrieved April 4, 2009.

- "In pictures: Norouz – New Year festival". BBC News. March 21, 2006. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Clashes erupt at Turkey's Dita e Verës. spring festival". Daily Star. March 22, 2006. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "BBCPersian.com". BBC. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Event - Second Annual Persian New Year Festival". AZFoothills.com. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- "Novruz... Celebration That Would Not Die". Azer.com. March 13, 1990. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- House Passes Historic Norooz (sic) Resolution, National Iranian American Council, March 15, 2010.

- Legislative Digest, GOP.gov, H.Res. 267. Archived March 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Malthe Conrad Bruun, Universal geography, or A description of all the parts of the world, Vol. II., London 1822, p. 282

- "Bush Sends Nowruz Greetings to Afghans". American Embassy Press Section. March 20, 2002. Archived from the original on February 2, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- Katrandjian, Olivia (May 16, 2010). "Booze and relative freedom lure Iranians to Christian enclave to the north". Los Angeles Times.

- Smbatian, Hasmik (March 23, 2011). "Iranians Flock To Armenia On Norouz Holiday". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- Mkrtchyan, Gayane (March 22, 2011). "Nowruz in Armenia: Many Iranians again prefer Yerevan for spending their New Year holiday". ArmeniaNow.

- Katrandjian, Olivia (May 16, 2010). "Postcard from Armenia". PBS.

- "President Sargsyan: Happy Nowruz to Armenia's Kurds and Iran". Hetq Online. March 21, 2015.

- "Studentsoftheworld – Azeri Traditions". Students of the World. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Nowruz Holiday". Azeri America. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- "Open air celebrations at Nowruz Bayram in Israel". Vestnik Kavkaza. Archived from the original on December 25, 2015. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- Koch, Ebba (2011), Duindam, Jeroen; Artan, Tülay; Kunt, Metin (eds.), "THE MUGHAL AUDIENCE HALL:: A SOLOMONIC REVIVAL OF PERSEPOLIS IN THE FORM OF A MOSQUE", Royal Courts in Dynastic States and Empires, A Global Perspective, Brill: 313–338, doi:10.1163/j.ctt1w8h2rh.19, JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h2rh.19

- "Nauroz Then and Now". Rana Safvi. March 20, 2015. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- Rofique, Rafiqul Islam. Banglapedia - National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- The celebration of Nawruz in Bukhara and Samarkand in ritual practice and social discourse (the second half of the 19th - the beginning of the 20th century) in Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia. volume 48. issue 2., 2020, pp.124-131.

- "Spring is in the air: Novruz in Tbilisi". Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- "Iranians in Georgia celebrate Nowruz". Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- "Nowruz Byram to be Celebrated in Tbilisi today". Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- "Public Defender congratulates Georgian citizens of Azeri Origin with Nowruz Bairam". Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- Pandey, Alpana (2015). Medieval Andhra: A Socio-Historical Perspective. Partridge Publishing. ISBN 978-1482850178.

- Pandey, Alpana (August 11, 2015). Medieval Andhra: A Socio-Historical Perspective. Partridge Publishing. ISBN 9781482850178.

- "Calendars" [The solar Hejrī (Š. = Šamsī) and Šāhanšāhī calendars]. Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- "Iran's festive drink and drugs binge". BBC World News. March 27, 2009.

- "Iran Public Holidays 2017". Mystery of Iran. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- "Divided views on Iran's new year". BBC World News. March 20, 2009.

- Michael Slackman (March 20, 2006). "Ayatollahs Aside, Iranians Jump for Joy at Spring". The New York Times.

- Jason Rezaian (March 21, 2013). "The politicization of Nowruz, Iran's new year". The Washington Post.

- "Kurdistan turco". Marcocavallini.it. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- Richter, Fabian (2016). Identität, Ethnizität und Nationalismus in Kurdistan (in German). LIT Verlag Münster. p. 55. ISBN 978-3643132345.

- Zaki Chehab, Inside the resistance: the Iraqi insurgency and the future of the Middle East, Published by Nation Books, 2005, ISBN 1-56025-746-6, p. 198

- "Turkish police arrest thousands". BBC News. March 22, 1999. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- Marianne Heiberg, Brendan O'Leary, John Tirman. Terror, Insurgency, and the State: Ending Protracted Conflicts, p. 337.

- "Turkey Kurds: PKK chief Ocalan calls for ceasefire". BBC News. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan Sperl (1991). The Kurds. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-07265-6.

- Amnesty International (March 16, 2004). "Syria: Mass arrests of Syrian Kurds and fear of torture and other ill-treatment". Archived from the original on November 19, 2006. Retrieved March 10, 2007.

- Yildiz, Kerim; Fryer, Georgina (2004). The Kurds: Culture and Language Rights. Kurdish Human Rights Project. ISBN 978-1-900175-74-6.

- "Three Kurds killed in Syria shooting, human rights group says – Middle East". Monsters And Critics. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- "Police kill three Kurds in northeast Syria – group". Reuters. March 21, 2008.

- Arab, The New. "Turkey bans Newroz celebrations for Syrian Kurds in Afrin". alaraby. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- Wahlbeck, Osten (1999). Kurdish Diasporas: A Comparative Study of Kurdish Refugee Communities. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-22067-9.

- "London celebrates Newroz: The Kurdish New Year". The Londoner. March 2006. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved March 10, 2007.

- Digest, Persia (April 1, 2018). "Nowruz in Pakistan – The kite festival". en. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- 10 (March 25, 2019). "Nowruz celebrated in Pakistan with Iran's active participation". IRNA English. Retrieved July 8, 2020.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Navroz". the.Ismaili. March 20, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- Mogul, Priyanka Mogul (March 18, 2016). "Nowruz 2016: Who are Persia's Zoroastrians and why is their festival being celebrated in India?". International Business Times. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- "Nowruz in the Twelver Shi'a faith". Rafed.net. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- "But they also celebrate some of the same festivals as the Christians, like Christmas and Epiphany, as well as Nauruz, which originally is the Zoroastrian New Year". I-cias.com. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "The Baha'i Calendar". Archived from the original on September 28, 2006. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- Walbridge, John (July 11, 2004). "Naw-Ruz: The Bahá'í New Year". Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- Esslemont, J.E. (1980). Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era (5th ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, US: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-0-87743-160-2.

- Lehman, Dale E. (March 18, 2000). "A New Year Begins". Planet Bahá'í. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- Bahá'u'lláh (1991). Bahá'í Prayers. Wilmitte, IL: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 261.

- Bahá'u'lláh (1992) [1873]. The Kitáb-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book. Wilmette, Illinois, US: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-85398-999-8.

- MacEoin, Dennis (1989). "Bahai Calendar and Festivals". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- `Abdu'l-Bahá (March 21, 1913). "Star of the West". 4 (1): 4. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) republished in Effendi, Shoghi; The Universal House of Justice (1983). Hornby, Helen (ed.). Lights of Guidance: A Bahá'í Reference File. Bahá'í Publishing Trust, New Delhi, India. ISBN 978-81-85091-46-4. - "Nowruz Persian New Year – Eid Mubarak! | Ismaili Web Amaana". Ismaili Web Amaana. March 15, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- "Navroz". The Ismaili. March 18, 2010. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- Mireskandari, Anousheh (March 2012). "Nowruz in Islam". Islamic Centre of England. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- Tahrir al Wasila, by Ayatollah Khomeini, Vol. 1, pp. 302–303

- Islamic Laws, by Ali al-Sistani, under the section; "Mustahab Fasts"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nowruz. |

.jpg)