Chaharshanbe Suri

Chaharshanbe Suri (Persian: چهارشنبهسوری, romanized: Čahār-šanba(-e)-sūrī;[1][2][3] lit. 'The Scarlet Wednesday', usually pronounced Čāršambe-sūrī)[1] is an Iranian festival celebrated on the eve of the last Wednesday before Nowruz (the Iranian New Year).[4][5]

| Chaharshanbe Suri | |

|---|---|

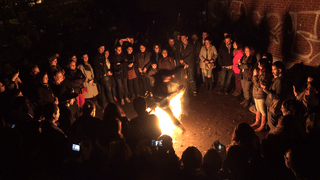

Charshanbe Suri in Tehran, March 2018. | |

| Observed by | |

| Type | National, ethnic, cultural |

| Date | The last Wednesday eve before the vernal equinox |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Nowruz, Sizdebedar |

Etymology

The Persian name of the festival consists of čahāršanbe (چهارشنبه), the name of Wednesday in the Iranian calendars, and suri (سوری), which has two meanings; it may mean "festive" [1] and it may also mean "scarlet" (in traditional persian and some current local dialects in Iran), which stems from the reddish theme of fire. In specific, since the fire has a basic role in this event, the latter meaning (i.e. the scarlet) makes more sense. Local varieties of the name of the festival include Azerbaijani Gūl Čāršamba (in Ardabil), Kurdish Kola Čowāršamba and Čowāršama Koli (in Kurdistan), and Isfahani Persian Čāršambe Sorxi (in Isfahan).[1] To the Yezidi Kurds, it is known as Çarşema Sor.[6]

Observances

Jumping over the fire

Before the start of the festival, people gather brushwood in an open, free exterior space. At sunset, after making one or more bonfires, they jump over the flames, singing sorxi-ye to az man, zardi-ye man az to, literally meaning "[let] your redness [be] mine, my paleness yours", or a local equivalent of it. This is considered a purification practice.[1]

Spoon-banging

Charshanbe Suri includes a custom similar to trick-or-treating that is called qāšoq-zani (قاشقزنی),[7] literally translated as "spoon-banging". It is observed by people wearing disguises and going door-to-door to hit spoons against plates or bowls and receive packaged snacks.

Historical background

Ancient Origin

The festival has its origin in ancient Iranian rituals. The ancient Iranians celebrated the festival of Hamaspathmaedaya (Hamaspaθmaēdaya), the last five days of the year in honor of the spirits of the dead, which is today referred to as Farvardinegan. They believed that the spirits of the dead would come for reunion. The seven holy immortals (Aməša Spənta) were honored, and were bidden a formal ritual farewell at the dawn of the New Year. The festival also coincided with festivals celebrating the creation of fire and humans. By the time of the Sasanian Empire, the festival was divided into two distinct pentads, known as the lesser and the greater panje. The belief had gradually developed that the "lesser panje" belonged to the souls of children and those who died without sin, while the "greater panje" was for all souls.

Qajar Empire

A custom once in vogue in Tehran was to seek the intercession of the so-called "Pearl Cannon" (Tup-e Morvārid) on the occasion of Charshanbe Suri. This heavy gun, which was cast by the foundry-man Ismāil Isfahāni in 1800, under the reign of Fath-Ali Shah of the Qajar dynasty, became the focus of many popular myths. Until the 1920s, it stood in Arg Square (میدان ارگ, Meydān-e Arg), to which the people of Tehran used to flock on the occasion of Charshanbe Suri. Spinsters and childless or unhappy wives climbed up and sat on the barrel or crawled under it, and mothers even made ill-behaved and troublesome children pass under it in the belief that doing so would cure their naughtiness. These customs died out in the 1920s, when the Pearl Cannon was moved to the Army's Officers' Club. There was also another Pearl Cannon in Tabriz. Girls and women used to fasten their dakhils (pieces of a paper or cloth inscribed with wishes and prayers) to its barrel on the occasion of Charshanbe Suri.[1] In times, the cannon had been used as a sanctuary for political or non-political fugitives to be immune to arrest or to protest from family problems.[8]

Sadegh Hedayat, an Iranian writer of prose fiction and short stories, has a book with the name of this cannon, Tup-e Morvārid, that criticize the old beliefs in Iranian folklore. The book also mentions the origin of the Pearl Cannon.

Today, the Pearl Cannon is placed in the opening of the Building Number 7 of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at 30th Tir Avenue, and the Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran is still in argument with the ministry to displace the gun to a museum.[9][10]

Gallery

- Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran, jumping over the fire.

Charshanbe Suri in Vancouver, March 2008.

Charshanbe Suri in Vancouver, March 2008. Charshanbe Suri in Berkeley, California, March 2013.

Charshanbe Suri in Berkeley, California, March 2013. Charshanbe Suri in New York City, March 2016.

Charshanbe Suri in New York City, March 2016.

References

- Kasheff, Manouchehr; Saʿīdī Sīrjānī, ʿAlī-Akbar (December 15, 1990). "ČAHĀRŠANBA-SŪRĪ". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. 6. IV. New York City: Bibliotheca Persica Press. pp. 630–634. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- Moeen, Mohammad, ed. (2002) [1972]. "چهارشنبهسوری" [Č.-šanba(-e)-sūrī]. Moeen Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Persian) (One-volume edition based on 6-volumes ed.). Tehran: Moeen Publications. ISBN 9789647603072.

- Mosaheb, Gholamhossein, ed. (2002) [1966]. "چهارشنبهسوری" [Čahār.Šanbe suri]. The Persian Encyclopedia (in Persian). 1 (2nd ed.). Tehran: Amirkabir. p. 811. ISBN 964303044X.

- Fu, Alison (March 13, 2013). "Persian fire-jumping festival delights Berkeley residents". The Daily Californian.

- https://surfiran.com/event/chaharshanbe-suri/

- Rodziewicz, A. (2016). "And the Pearl Became an Egg: The Yezidi Red Wednesday and Its Cosmogonic Background". Iran and the Caucasus. 20: 347–367.

- American Folklife Center (1991). Folklife Center News. 13. Library of Congress. p. 6.

- "توپ مروارید". Encyclopaedia Islamica (in Persian). Archived from the original on March 16, 2014.

- "توپ مرواريد گرفتار غفلت چهارده ماهه وزارت خارجه". Iran's Cultural Heritage News Agency (in Persian). Archived from the original on May 24, 2008.

- "مكاتبه براي نجات توپ مرواريداز سر گرفته مي شود". Iran's Cultural Heritage News Agency (in Persian). Archived from the original on May 24, 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chaharshanbe Suri. |