List of communist ideologies

Communist ideologies notable enough in the history of communism include philosophical, social, political and economic ideologies and movements whose ultimate goal is the establishment of a communist society, a socioeconomic order structured upon the ideas of common ownership of the means of production and the absence of social classes, money[1][2] and the state.[3][4]

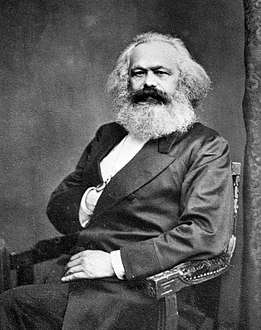

Self-identified communists hold a variety of views, including libertarian communism (anarcho-communism and council communism), Marxist communism (left communism, Leninism, libertarian Marxism, Maoism, Marxism–Leninism and Trotskyism) and pre- or non-Marxist, religious communism (Christian communism, Islamic communism and Jewish communism). While it originates from the works of 19th-century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Marxist communism has developed into many different branches and schools of thought, with the result that there is now no single definitive Marxist theory.[5]

Different communist schools of thought place a greater emphasis on certain aspects of classical Marxism while rejecting or modifying other aspects. Many communist schools of thought have sought to combine Marxian concepts and non-Marxian concepts which has then led to contradictory conclusions.[6] However, there is a movement toward the recognition that historical materialism and dialectical materialism remains the fundamental aspect of all Marxist communist schools of thought.[7] The offshoots of Marxism–Leninism are the most well-known of these and have been a driving force in international relations during most of the 20th century.[8]

Marxist communism

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that views class relations and social conflict using a materialist interpretation of historical development and takes a dialectical view of social transformation. It originates from the works of 19th-century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Classical Marxism is the economic, philosophical and sociological theories expounded by Marx and Engels as contrasted with later developments in Marxism, especially Leninism and Marxism–Leninism.[9]

Orthodox Marxism is the body of Marxism thought that emerged after the death of Marx and which became the official philosophy of the socialist movement as represented in the Second International until World War I in 1914. Orthodox Marxism aims to simplify, codify and systematize Marxist method and theory by clarifying the perceived ambiguities and contradictions of classical Marxism. The philosophy of orthodox Marxism includes the understanding that material development (advances in technology in the productive forces) is the primary agent of change in the structure of society and of human social relations and that social systems and their relations (e.g. feudalism, capitalism and so on) become contradictory and inefficient as the productive forces develop, which results in some form of social revolution arising in response to the mounting contradictions. This revolutionary change is the vehicle for fundamental society-wide changes and ultimately leads to the emergence of new economic systems.[10]

As a term, orthodox Marxism refers to the methods of historical materialism and of dialectical materialism and not the normative aspects inherent to classical Marxism, without implying dogmatic adherence to the results of Marx's investigations.[11]

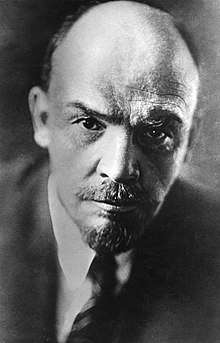

Leninism

Leninism is a political theory for the organisation of a revolutionary vanguard party and the achievement of a dictatorship of the proletariat as political prelude to the establishment of socialism. Developed by and named for the Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, Leninism comprises political and economic theories developed from orthodox Marxism and Lenin's interpretations of Marxist theories, including his original theoretical contributions such as his analysis of imperialism, principles of party organization and the implementation of socialism through revolution and reform thereafter, for practical application to the socio-political conditions of the Russian Empire of the early 20th century.

Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a political ideology developed by Joseph Stalin in the late 1920s. Based on Stalin's understanding and synthesis of both Marxism and Leninism, it was the official state ideology of the Soviet Union and the parties of the Communist International after Bolshevisation. After the death of Lenin in 1924, Stalin established universal ideologic orthodoxy among the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), the Soviet Union and the Communist International to establish universal Marxist–Leninist praxis. In the late 1930s, Stalin's official textbook The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) (1938), made the term Marxism–Leninism common political-science usage among communists and non-communists.

The purpose of Marxism–Leninism is the revolutionary transformation of a capitalist state into a socialist state by way of two-stage revolution led by a vanguard party of professional revolutionaries, drawn from the proletariat. To realise the two-stage transformation of the state, the vanguard party establishes the dictatorship of the proletariat and determines policy through democratic centralism. The Marxist–Leninist communist party is the vanguard for the political, economic and social transformation of a capitalist society into a socialist society which is the lower stage of socio-economic development and progress towards the upper-stage communist society which is stateless and classless, yet it features public ownership of the means of production, accelerated industrialisation, pro-active development of society's productive forces (research and development) and nationalized natural resources.

As the official ideology of the Soviet Union, Marxism–Leninism was adopted by communist parties worldwide with variation in local application. Parties with a Marxist–Leninist understanding of the historical development of socialism advocate for the nationalisation of natural resources and monopolist industries of capitalism and for their internal democratization as part of the transition to workers' control. The economy under such a government is primarily coordinated through a universal economic plan with varying degrees of market distribution. Since the fall of the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries, many communist parties of the world today continue to use Marxism–Leninism as their method of understanding the conditions of their respective countries.

Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and related policies implemented from 1927 to 1953 by Stalin. Stalinist policies and ideas that were developed in the Soviet Union included rapid industrialization, the theory of socialism in one country, collectivization of agriculture and subordination of the interests of foreign communist parties to those of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), deemed by Stalinism to be the leading vanguard party of communist revolution at the time.

As a political term, it has a variety of uses, but most commonly it is used as a pejorative shorthand for Marxism–Leninism by a variety of competing political tendencies such as capitalism and Trotskyism. Although Stalin himself repudiated any qualitatively original contribution to Marxism, the communist movement usually credits him with systematizing and expanding the ideas of Lenin into the ideology of Marxism–Leninism as a distinct body of work. In this sense, Stalinism can be thought of as being roughly equivalent to Marxism–Leninism, although this is not universally agreed upon. At other times, the term is used as a general umbrella term—again pejoratively—to describe a wide variety of political systems and governments, including the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc and Warsaw Pact countries of Europe, Mongolia, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Ethiopia and others. In this sense, it can be seen as being roughly equivalent to actually existing socialism, although sometimes it is used to describe totalitarian governments that are not socialist.

At any rate, some of the contributions to communist theory that Stalin is particularly known for are the following:

- The theoretical work concerning nationalities as seen in Marxism and the National Question.[12]

- The notion of socialism in one country.

- Marxist theory of linguistics.

- The theory of aggravation of class struggle under socialism, a theoretical base supporting the repression of political opponents as necessary.

Trotskyism

Leon Trotsky and his supporters organized into the Left Opposition and their platform became known as Trotskyism. Stalin eventually succeeded in gaining control of the Soviet regime and Trotskyist attempts to remove Stalin from power resulted in Trotsky's exile from the Soviet Union in 1929. During Trotsky's exile, mainstream communism fractured into two distinct branches, i.e. Trotskyism and Stalinism.[8] Trotskyism supports the theory of permanent revolution and world revolution instead of the two stage theory and socialism in one country. It supported proletarian internationalism and another communist revolution in the Soviet Union which Trotsky claimed had become a degenerated worker's state under the leadership of Stalin in which class relations had re-emerged in a new form, rather than the dictatorship of the proletariat. In 1938, Trotsky founded the Fourth International, a Trotskyist rival to the Stalinist Communist International.

Trotskyist ideas have found echo among political movements in some countries in Asia and Latin America, especially in Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia and Sri Lanka. Many Trotskyist organizations are also active in more stable, developed countries in North America and Western Europe. Trotsky's politics differed sharply from those of Stalin and Mao, most importantly in declaring the need for an international proletarian revolution (rather than socialism in one country) and unwavering support for a true dictatorship of the proletariat based on democratic principles. As a whole, Trotsky's theories and attitudes were never accepted in Marxist–Leninist circles after Trotsky's expulsion, either within or outside of the Soviet Bloc. This remained the case even after the "Secret Speech" and subsequent events critics claim exposed the fallibility of Stalin.

Trotsky's followers claim to be the heirs of Lenin in the same way that mainstream Marxist–Leninists do. There are several distinguishing characteristics of this school of thought—foremost is the theory of permanent revolution, contrasted to the theory of socialism in one country. This stated that in less-developed countries the bourgeoisie were too weak to lead their own bourgeois-democratic revolutions. Due to this weakness, it fell to the proletariat to carry out the bourgeois revolution. With power in its hands, the proletariat would then continue this revolution permanently, transforming it from a national bourgeois revolution to a socialist international revolution.[13] Another shared characteristic between Trotskyists is a variety of theoretical justifications for their negative appraisal of the post-Lenin Soviet Union after Trotsky was expelled by a majority vote from the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)[14] and subsequently from the Soviet Union. As a consequence, Trotsky defined the Soviet Union under Stalin as a planned economy ruled over by a bureaucratic caste. Trotsky advocated overthrowing the government of the Soviet Union after he was expelled from it.[15]

Maoism

Maoism is the Marxist–Leninist trend of communism associated with Mao Zedong and was mostly practised within the People's Republic of China. Khrushchev's reforms heightened ideological differences between the China and the Soviet Union, which became increasingly apparent in the 1960s. As the Sino-Soviet split in the international communist movement turned toward open hostility, China portrayed itself as a leader of the underdeveloped world against the two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union.

Parties and groups that supported the Communist Party of China in their criticism against the new Soviet leadership proclaimed themselves as anti-revisionist and denounced the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the parties aligned with it as revisionist "capitalist roaders". The Sino-Soviet split resulted in divisions amongst communist parties around the world. Notably, the Party of Labour of Albania sided with the People's Republic of China. Effectively, the communist party under Mao Zedong's leadership became the rallying forces of a parallel international communist tendency. The ideology of the Chinese communist party, Marxism–Leninism–Mao Zedong Thought (generally referred to as Maoism), was adopted by many of these groups.

After Mao's death and his replacement by Deng Xiaoping, the international Maoist movement diverged. One sector accepted the new leadership in China whereas a second renounced the new leadership and reaffirmed their commitment to Mao's legacy and a third renounced Maoism altogether and aligned with Albania.

Dengism

Dengism is a political and economic ideology first developed by Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping. The theory does not claim to reject Marxism–Leninism or Mao Zedong Thought, but instead it seeks to adapt them to the existing socio-economic conditions of China. Deng also stressed opening China to the outside world, the implementation of one country, two systems and through the phrase "seek truth from facts" an advocation of political and economic pragmatism.

As reformist communism and a branch of Maoism, Dengism is often criticized by traditional Maoists. Dengists believe that isolated in our current international order and with an extremely underdeveloped economy it is first and foremost necessary to bridge the gap between China and Western capitalism as quickly as possible in order for socialism to be successful (see the theory of primary stage of socialism). In order to encourage and promote the advancement of the productivity by creating competition and innovation, Dengist thought promotes the idea that the PRC needs to introduce a certain market element in a socialist country. Dengists still believe that China needs public ownership of land, banks, raw materials and strategic central industries so a democratically elected government can make decisions on how to use them for the benefit of the country as a whole instead of the land owners, but at the same time private ownership is allowed and encouraged in industries of finished goods and services.[16][17][18] According to the Dengist theory, private owners in those industries are not a bourgeoisie. Because in accordance with Marxist theory, bourgeois owns land and raw materials. In Dengist theory, private company owners are called civil run enterprises. China was the first country that adopted this belief. It boosted its economy and achieved the Chinese economic miracle. It has increased the Chinese GDP growth rate to over 8% per year for thirty years and China now has the second highest GDP in the world. Due to the influence of Dengism, Vietnam and Laos have also adopted this belief, allowing Laos to increase its real GDP growth rate to 8.3%.[19] Cuba is also starting to embrace this idea.

Dengists take a very strong position against any form of personality cults which appeared in the Soviet Union during Stalin's rule and the current North Korea.[20][21]

Marxism–Leninism–Maoism

Marxism–Leninism–Maoism is a political philosophy that builds upon Marxism–Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought. It was first formalised by the Peruvian communist party Shining Path in 1988.

The synthesis of Marxism–Leninism–Maoism did not occur during the life of Mao. From the 1960s, groups that called themselves Maoist, or which upheld Marxism–Leninism–Mao Zedong Thought, were not unified around a common understanding of Maoism and had instead their own particular interpretations of the political, philosophical, economical and military works of Mao. Maoism as a unified, coherent stage of Marxism was not synthesized until the late 1980s through the experience of the people's war waged by the Shining Path. This led the Shining Path to posit Maoism as the newest development of Marxism in 1988.

Since then, it has grown and developed significantly and has served as an animating force of revolutionary movements in countries such as Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, India, Nepal and the Philippines and has also led to efforts being undertaken towards the constitution or reconstitution of communist parties in countries such as Austria, France, Germany, Sweden and the United States.

Prachanda Path

Marxism–Leninism–Maoism–Prachanda Path is the ideological line of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist). It is considered to be a further development of Marxism–Leninism and Maoism. It is named after the leader of the CPN(M), Pushpa Kamal Dahal, commonly known as Prachanda. Prachanda Path was proclaimed in 2001 and its formulation was partially inspired by the Shining Path which refers to its ideological line as Marxism–Leninism–Maoism–Gonzalo Thought. Prachanda Path does not make an ideological break with Marxism–Leninism or Maoism, but rather it is an extension of these ideologies based on the political situation of Nepal. The doctrine came into existence after it was realized that the ideology of Marxism–Leninism and Maoism could not be practiced as done in the past, therefore Prachanda Path based on the circumstances of Nepalese politics was adopted by the party.

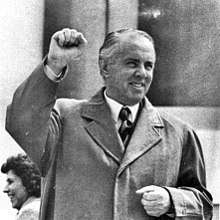

Hoxhaism

Hoxhaism is an anti-revisionist Marxist-Leninist variant that appeared after the ideological row between the Communist Party of China and the Party of Labour of Albania in 1978. The Albanians rallied a new separate international tendency. This tendency would demarcate itself by a strict defense of the legacy of Stalin and fierce criticism of virtually all other communist groupings as revisionist.

Critical of the United States, Soviet Union and China, Enver Hoxha declared the latter two to be social-imperialist and condemned the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia by withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact in response. Hoxha declared Albania to be the world's only state legitimately adhering to Marxism–Leninism after 1978. The Albanians were able to win over a large share of the Maoists, mainly in Latin America such as the Popular Liberation Army and the Marxist–Leninist Communist Party of Ecuador, but it also had a significant international following in general. This tendency has occasionally been labeled as Hoxhaism after him.

After the fall of the communist government in Albania, the pro-Albanian parties are grouped around an international conference and the publication Unity and Struggle.

Titoism

Titoism is described as the post-World War II policies and practices associated with Josip Broz Tito during the Cold War, characterized by an opposition to the Soviet Union.

Elements of Titoism are characterized by policies and practices based on the principle that in each country, the means of attaining ultimate communist goals must be dictated by the conditions of that particular country rather than by a pattern set in another country. During Josip Broz Tito's era, this specifically meant that the communist goal should be pursued independently of and often in opposition to the policies of the Soviet Union. The term was originally meant as a pejorative and was labeled by Moscow as a heresy during the period of tensions between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia known as the Informbiro period from 1948 to 1955.

Unlike the rest of Eastern Bloc which fell under Stalin's influence post-World War II, Yugoslavia remained independent from Moscow due to the strong leadership of Marshal Tito and the fact that the Yugoslav Partisans liberated Yugoslavia with only limited help from the Red Army. It became the only country in the Balkans to resist pressure from Moscow to join the Warsaw Pact and remained "socialist, but independent" right up until the collapse of Soviet socialism in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Throughout his time in office, Joseph Broz Tito prided himself on Yugoslavia's independence from the Soviet Bloc, with Yugoslavia never accepting full membership of the Comecon and his open rejection of many aspects of Stalinism as the most obvious manifestations of this.

Although himself not a communist, Muammar Gaddafi's Third International Theory was heavily influenced by Titoism.[22]

Eurocommunism

Eurocommunism was a revisionist trend in the 1970s and 1980s within various Western European communist parties which said they had developed a theory and practice of social transformation more relevant for Western Europe. During the Cold War, they sought to undermine the influence of the Soviet Union and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It was especially prominent in France, Italy and Spain.

Since the early 1970s, the term Eurocommunism was used to refer to the ideology of moderate, reformist communist parties in Western Europe. These parties did not support the Soviet Union and denounced its policies. Such parties were politically active and electorally significant in France, Italy and Spain.[23]

Luxemburgism

Luxemburgism is a specific revolutionary theory within Marxism and communism based on the writings of Rosa Luxemburg.

Council communism

Council communism is a movement originating from Germany and the Netherlands in the 1920s. The Communist Workers Party of Germany (KAPD) was the primary organization that espoused council communism. Council communism continues today as a theoretical and activist position within both Marxism and libertarian socialism. As such, it is referred to as anti-authoritarian and anti-Leninist Marxism.

In contrast to reformist social democracy and to Leninism, the central argument of council communism is that democratic workers councils arising in factories and municipalities are the natural form of working class organisation and governmental power. This view is also opposed to the social democratic and Marxist–Leninist ideologies, with their stress on parliaments and institutional government (i.e. by applying social reforms) on the one hand and vanguard parties and participative democratic centralism on the other.

The core principle of council communism is that the government and the economy should be managed by workers' councils composed of delegates elected at workplaces and recallable at any moment. As such, council communists oppose authoritarian socialism. They also oppose the idea of a revolutionary party since council communists believe that a party-led revolution will necessarily produce a party dictatorship. Council communists support a worker's democracy which they want to produce through a federation of workers' councils. Council communism and other types of libertarian Marxism such as autonomism are often viewed as being similar to anarchism because they criticize Leninist ideologies for being authoritarian and reject the idea of a vanguard party.

De Leonism

De Leonism is a form of Marxism developed by the American activist Daniel De Leon. De Leon was an early leader of the first socialist political party in the United States, the Socialist Labor Party of America. De Leon combined the rising theories of syndicalism in his time with orthodox Marxism.

Non-Marxist communism

The most widely held forms of communist theory are derived from Marxism, but non-Marxist versions of communism also exist and are growing in importance since the fall of the Soviet Union.

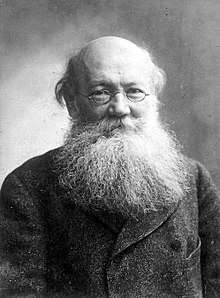

Anarcho-communism

Some of Marx's contemporaries espoused similar ideas, but differed in their views of how to reach to a classless society. Following the split between those associated with Marx and Mikhail Bakunin at the First International, the anarchists formed the International Workers Association.[24] Anarchists argued that capitalism and the state were inseparable and that one could not be abolished without the other. Anarcho-communists such as Peter Kropotkin theorized an immediate transition to one society with no classes. Anarcho-syndicalism became one of the dominant forms of anarchist organization, arguing that labor unions are the organizations that can change society as opposed to communist parties. Consequently, many anarchists have been in opposition to Marxist communism to this day.

Religious communism

Religious communism is a form of communism that incorporates religious principles. Scholars have used the term to describe a variety of social or religious movements throughout history that have favored the common ownership of property.

Christian communism

Christian communism is a form of religious communism centered on Christianity. It is a theological and political theory based upon the view that the teachings of Jesus Christ urge Christians to support communism as the ideal social system. Christian communists trace the origins of their practice to teachings in the New Testament, such as this one from Acts of the Apostles at chapter 2 and verses 42, 44 and 45:

42. And they continued steadfastly in the apostles' doctrine and in fellowship [...] 44. And all that believed were together, and had all things in common; 45. And sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need. (King James Version)

Christian communism can be seen as a radical form of Christian socialism and because many Christian communists have formed independent stateless communes in the past, there is also a link between Christian communism and Christian anarchism. Christian communists may or may not agree with various parts of Marxism.

Christian communists also share some of the political goals of Marxists, for example replacing capitalism with socialism, which should in turn be followed by communism at a later point in the future. However, Christian communists sometimes disagree with Marxists (and particularly with Leninists) on the way a socialist or communist society should be organized.

21st-century communist theorists

According to the political theorist Alan Johnson, there has been a revival of serious interest in communism in the 21st century led by Slavoj Zizek and Alain Badiou. Other leading theorists are Michael Hardt, Toni Negri, Gianni Vattimo, Alessandro Russo and Judith Balso as well as Alberto Toscano, translator of Alain Badiou, Terry Eagleton and Bruno Bosteels. In 2009, many of these advocates contributed to the three-day conference "The Idea of Communism" in London that drew a substantial paying audience. Theoretical publications, some published by Verso Books, include The Idea of Communism, edited by Costas Douzinas and Zizek; Badiou's The Communist Hypothesis; and Bosteels's The Actuality of Communism. The defining common ground is the contention that "the crises of contemporary liberal capitalist societies—ecological degradation, financial turmoil, the loss of trust in the political class, exploding inequality—are systemic, interlinked, not amenable to legislative reform, and require "revolutionary" solutions".[25]

References

Notes

- Engels, Friedrich (1847). Principles of Communism. Section 18. "Finally, when all capital, all production, all exchange have been brought together in the hands of the nation, private property will disappear of its own accord, money will become superfluous, and production will so expand and man so change that society will be able to slough off whatever of its old economic habits may remain".

- Bukharin, Nikolai (1920). The ABC of Communism. Section 20.

- Bukharin, Nikolai (1920). The ABC of Communism. Section 21.

- Kurian, George Thomas, ed. (2011). "Withering Away of the State". The Encyclopedia of Political Science. CQ Press. doi:10.4135/9781608712434. ISBN 978-1-933116-44-0. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- Wolff and Resnick, Richard and Stephen (August 1987). Economics: Marxian versus Neoclassical. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-8018-3480-6.

The German Marxists extended the theory to groups and issues Marx had barely touched. Marxian analyses of the legal system, of the social role of women, of foreign trade, of international rivalries among capitalist nations, and the role of parliamentary democracy in the transition to socialism drew animated debates. [...] Marxian theory (singular) gave way to Marxian theories (plural).

- O'Hara, Phillip (September 2003). Encyclopedia of Political Economy, Volume 2. Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-415-24187-8.

Marxist political economists differ over their definitions of capitalism, socialism and communism. These differences are so fundamental, the arguments among differently persuaded Marxist political economists have sometimes been as intense as their oppositions to political economies that celebrate capitalism.

- Ermak, Gennady (2019). Communism: The Great Misunderstanding. ISBN 978-1797957388.

- "Communism". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). 2007.

- Gluckstein, Donny (26 June 2014). "Classical Marxism and the question of reformism". International Socialism. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Rees, John (July 1998). The Algebra of Revolution: The Dialectic and the Classical Marxist Tradition. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415198776.

- Lukács, Georg. What is Orthodox Marxism?. Marxism Internet Archive (1919): "What is Orthodox Marxism?". "Orthodox Marxism, therefore, does not imply the uncritical acceptance of the results of Marx's investigations. It is not the 'belief' in this or that thesis, nor the exegesis of a 'sacred' book. On the contrary, orthodoxy refers exclusively to method."

- "Marxism and the National Question". www.marxists.org.

- Trotsky, Leon (1931). The Permanent Revolution.

The Permanent Revolution is Not a ‘Leap’ by the Proletariat, but the Reconstruction of the Nation under the Leadership of the Proletariat.

- Rubenstein, Joshua (2011). Leon Trotsky: A Revolutionary's Life. Hartford, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 155–202. ISBN 9780300137248.

- Getty, J. Arch (January 1986). "Trotsky in Exile: The Founding of the Fourth International". Soviet Studies. Oxford, England: Taylor & Francis. 38 (1): 24–35. doi:10.1080/09668138608411620.

- http://english.cpc.people.com.cn/mediafile/200607/05/F2006070515295500635.swf

- http://english.cpc.people.com.cn/mediafile/200607/05/F2006070515261400629.swf

- http://english.cpc.people.com.cn/mediafile/200607/05/F2006070515274900631.swf

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "(五)邓小平对个人崇拜的批判--读书--人民网". book.people.com.cn.

- "邓小平八大发言:坚持民主集中制 反对个人崇拜-历史频道-手机搜狐". m.sohu.com.

- http://www.h-alter.org/vijesti/libijska-dzamahirija-zmedju-proslosti-i-sadasnjosti-1-dio

- Colton, Timothy J. (2007). "Communism". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009.

- Marshall, Peter (1993). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Fontana Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1.

- Johnson, Alan (May–June 2012). "The New Communism: Resurrecting the Utopian Delusion". World Affairs.

A specter is haunting the academy—the specter of "new communism." A worldview recently the source of immense suffering and misery, and responsible for more deaths than fascism and Nazism, is mounting a comeback; a new form of left-wing totalitarianism that enjoys intellectual celebrity but aspires to political power.

External links

- In Defense of Marxism

- Comprehensive list of the leftist parties of the world

- Anarchy Archives

- RevoltLib

- Libertarian Communist Library

- Marxists Internet Archive

- Marxist.net

- The Mu Particle in "Communism", a short etymological essay by Wu Ming

- Open Society Archives, one of the biggest history of communism and Cold War archives in the world

- The Anarchist Library

.jpg)

.jpg)