Cookware and bakeware

Cookware and bakeware are types of food preparation containers, commonly found in a kitchen. Cookware comprises cooking vessels, such as saucepans and frying pans, intended for use on a stove or range cooktop. Bakeware comprises cooking vessels intended for use inside an oven. Some utensils are considered both cookware and bakeware.

.jpg)

Cookware and Bakeware are extremely broad and particular materials can widen this spectrum as it affects both the quality of the item as well as the food that comes out of it, particularly in terms of thermal conductivity and how much food sticks to the item when in use. Some choices of material also require special pre-preparation of the surface—known as seasoning—before they are used for food preparation.

Both the cooking pot and lid handles can be made of the same material but will mean that, when picking up or touching either of these parts, oven gloves will need to be worn. In order to avoid this, handles can be made of non-heat-conducting materials, for example bakelite, plastic or wood. It is best to avoid hollow handles because they are difficult to clean or to dry.

A good cooking pot design has an "overcook edge" which is what the lid lies on. The lid has a dripping edge that prevents condensation fluid from dripping off when handling the lid (taking it off and holding it 45°) or putting it down.

History

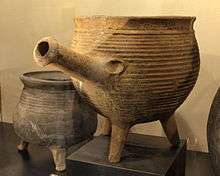

The history of cooking vessels before the development of pottery is minimal due to the limited archaeological evidence. The earliest pottery vessels, dating from 19,600±400 BP, were discovered in Xianrendong Cave, Jiangxi, China. The pottery may have been used as cookware, manufactured by hunter-gatherers.[1] Harvard University archaeologist Ofer Bar-Yosef reported that "When you look at the pots, you can see that they were in a fire."[2] It is also possible to extrapolate likely developments based on methods used by latter peoples. Among the first of the techniques believed to be used by Stone Age civilizations were improvements to basic roasting. In addition to exposing food to direct heat from either an open fire or hot embers it is possible to cover the food with clay or large leaves before roasting to preserve moisture in the cooked result. Examples of similar techniques are still in use in many modern cuisines.[3]

Of greater difficulty was finding a method to boil water. For people without access to natural heated water sources, such as hot springs, heated stones ("pot boilers") could be placed in a water-filled vessel to raise its temperature (for example, a leaf-lined pit or the stomach from animals killed by hunters).[4] In many locations the shells of turtles or large mollusks provided a source for waterproof cooking vessels. Bamboo tubes sealed at the end with clay provided a usable container in Asia, while the inhabitants of the Tehuacan Valley began carving large stone bowls that were permanently set into a hearth as early as 7,000 BC.

According to Frank Hamilton Cushing, Native American cooking baskets used by the Zuni (Zuñi) developed from mesh casings woven to stabilize gourd water vessels. He reported witnessing cooking basket use by Havasupai in 1881. Roasting baskets covered with clay would be filled with wood coals and the product to be roasted. When the thus-fired clay separated from the basket, it would become a usable clay roasting pan in itself. This indicates a steady progression from use of woven gourd casings to waterproof cooking baskets to pottery. Other than in many other cultures, Native Americans used and still use the heat source inside the cookware. Cooking baskets are filled with hot stones and roasting pans with wood coals.[5] Native Americans would form a basket from large leaves to boil water, according to historian and novelist Louis L'Amour. As long as the flames did not reach above the level of water in the basket, the leaves would not burn through.

The development of pottery allowed for the creation of fireproof cooking vessels in a variety of shapes and sizes. Coating the earthenware with some type of plant gum, and later glazes, converted the porous container into a waterproof vessel. The earthenware cookware could then be suspended over a fire through use of a tripod or other apparatus, or even be placed directly into a low fire or coal bed as in the case of the pipkin. Ceramics conduct heat poorly, however, so ceramic pots must cook over relatively low heats and over long periods of time. However, most ceramic pots will crack if used on the stovetop, and are only intended for the oven.

The development of bronze and iron metalworking skills allowed for cookware made from metal to be manufactured, although adoption of the new cookware was slow due to the much higher cost. After the development of metal cookware there was little new development in cookware, with the standard Medieval kitchen utilizing a cauldron and a shallow earthenware pan for most cooking tasks, with a spit employed for roasting.[6][7]

By the 17th century, it was common for a Western kitchen to contain a number of skillets, baking pans, a kettle and several pots, along with a variety of pot hooks and trivets. Brass or copper vessels were common in Asia and Europe, whilst iron pots were common in the American colonies. Improvements in metallurgy during the 19th and 20th centuries allowed for pots and pans from metals such as steel, stainless steel and aluminium to be economically produced.[7]

At the 1968 Miss America protest, protestors symbolically threw a number of feminine products into a "Freedom Trash Can", which included pots and pans.[8]

Cookware materials

Metal

Metal pots are made from a narrow range of metals because pots and pans need to conduct heat well, but also need to be chemically unreactive so that they do not alter the flavor of the food. Most materials that are conductive enough to heat evenly are too reactive to use in food preparation. In some cases (copper pots, for example), a pot may be made out of a more reactive metal, and then tinned or clad with another.

Aluminium

Aluminium is a lightweight metal with very good thermal conductivity. It is resistant to many forms of corrosion. Aluminium is commonly available in sheet, cast, or anodized forms,[9] and may be physically combined with other metals (see below).

Sheet aluminium is spun or stamped into form. Due to the softness of the metal, it may be alloyed with magnesium, copper, or bronze to increase its strength. Sheet aluminium is commonly used for baking sheets, pie plates, and cake or muffin pans. Deep or shallow pots may be formed from sheet aluminium.

Cast aluminium can produce a thicker product than sheet aluminium, and is appropriate for irregular shapes and thicknesses. Due to the microscopic pores caused by the casting process, cast aluminium has a lower thermal conductivity than sheet aluminium. It is also more expensive. Accordingly, cast aluminium cookware has become less common. It is used, for example, to make Dutch ovens lightweight and bundt pans heavy duty, and used in ladles and handles and woks to keep the sides at a lower temperature than the center.

Anodized aluminium has had the naturally occurring layer of aluminium oxide thickened by an electrolytic process to create a surface that is hard and non-reactive. It is used for sauté pans, stockpots, roasters, and Dutch ovens.[9]

Uncoated and un-anodized aluminium can react with acidic foods to change the taste of the food. Sauces containing egg yolks, or vegetables such as asparagus or artichokes may cause oxidation of non-anodized aluminium.

Aluminium exposure has been suggested as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease.[10][11][12] The Alzheimer's Association states that "studies have failed to confirm any role for aluminum in causing Alzheimer's."[13] The link remains controversial.[14]

Copper

Copper provides the highest thermal conductivity among non-noble metals and is therefore fast heating with unparalleled heat distribution (see: Copper in heat exchangers). Pots and pans are cold-formed from copper sheets of various thicknesses, with those in excess of 2.5 mm considered commercial (or extra-fort) grade. Between 1 mm and 2.5 mm wall thickness is considered utility (fort) grade, with thicknesses below 1.5 mm often requiring tube beading or edge rolling for reinforcement. Less than 1mm wall thickness is generally considered decorative, with exception made for the case of .75–1 mm planished copper, which is hardened by hammering and therefore expresses performance and strength characteristic of thicker material.

Copper thickness of less than .25 mm is, in the case of cookware, referred to as foil and must be formed to a more structurally rigid metal to produce a serviceable vessel. Such applications of copper are purely aesthetic and do not materially contribute to cookware performance.

Copper is reactive with acidic foods which can result in corrosion, the byproducts of which can foment copper toxicity. In certain circumstances, however, unlined copper is recommended and safe, for instance in the preparation of meringue, where copper ions prompt proteins to denature (unfold) and enable stronger protein bonds across the sulfur contained in egg whites. Unlined copper is also used in the making of preserves, jams and jellies. Copper does not store ("bank") heat, and so thermal flows reverse almost immediately upon removal from heat. This allows precise control of consistency and texture while cooking sugar and pectin-thickened preparations. Alone, fruit acid would be sufficient to cause leaching of copper byproducts, but naturally occurring fruit sugars and added preserving sugars buffer copper reactivity. Unlined pans have thereby been used safely in such applications for centuries.

Lining copper pots and pans prevents copper from contact with acidic foods. The most popular lining types are tin, stainless steel, nickel and silver.

The use of tin dates back many centuries and is the original lining for copper cookware. Although the patent for canning in sheet tin was secured in 1810 in England, legendary French chef Auguste Escoffier experimented with a solution for provisioning the French army while in the field by adapting the tin lining techniques used for his cookware to more robust steel containers (then only lately introduced for canning) which protected the cans from corrosion and soldiers from lead solder and botulism poisoning.

Tin linings sufficiently robust for cooking are wiped onto copper by hand, producing a .35–45-mm-thick lining.[15] Decorative copper cookware, i.e., a pot or pan less than 1 mm thick and therefore unsuited to cooking, will often be electroplate lined with tin. Should a wiped tin lining be damaged or wear out the cookware can be re-tinned, usually for much less cost than the purchase price of the pan. Tin presents a smooth crystalline structure and is therefore relatively non-stick in cooking applications. As a relatively soft metal abrasive cleansers or cleaning techniques can accelerate wear of tin linings. Wood, silicone or plastic implements are to preferred over harder stainless steel types.

For a period following the Second World War, pure nickel was electroplated as a lining to copper cookware. Nickel had the advantage of being harder and more thermally efficient than tin, with a higher melting point. Despite its hardness nickel's wear characteristics were similar to that of tin, as nickel would be plated only to a thickness of <20 microns, and often even less owing to nickel's tendency to plate somewhat irregularly, requiring milling to produce an even cooking surface, albeit sticky compared to tin and silver. Copper cookware with aged or damaged nickel linings is eligible for retinning, or possibly replating with nickel, although this service is difficult if not impossible to find in the US and Europe in the early 21st century. Nickel linings began to fall out of favor in the 1980s owing to the isolation of nickel as an allergen.

Silver is also applied to copper by means of electroplating, and provides an interior finish that is at once smooth, more durable than either tin or nickel, relatively non-stick and extremely thermally efficient. Copper and silver bond extremely well owing to their shared high electro-conductivity. Lining thickness varies widely by maker, but averages between 7 and 10 microns. The disadvantages of silver are expense and the tendency of sulfurous foods, especially brassicas, to discolor. Worn silver linings on copper cookware can be restored by stripping and re-electroplating.

Copper cookware lined with a thin layer of stainless steel is available from most modern European manufacturers. Stainless steel is 25 times less thermally conductive than copper, and is sometimes critiqued for compromising the efficacy of the copper with which it is bonded. Among the advantages of stainless steel are its durability and corrosion resistance, and although relatively sticky and subject to food residue adhesions, stainless steel is tolerant of most abrasive cleaning techniques and metal implements. Stainless steel forms a pan's structural element when bonded to copper and is irreparable in the event of wear or damage.

Using modern metal bonding techniques, such as cladding, copper is frequently incorporated into cookware constructed of primarily dissimilar metal, such as stainless steel, often as an enclosed diffusion layer (see coated and composite cookware below).

Cast iron

Cast-iron cookware is slow to heat, but once at temperature provides even heating. Cast iron can also withstand very high temperatures, making cast iron pans ideal for searing. Being a reactive material, cast iron can have chemical reactions with high acid foods such as wine or tomatoes. In addition, some foods (such as spinach) cooked on bare cast iron will turn black.

Cast iron is a porous material that rusts easily. As a result, it typically requires seasoning before use. Seasoning creates a thin layer of oxidized fat over the iron that coats and protects the surface, and prevents sticking.

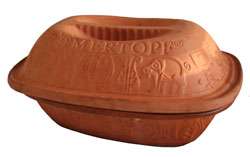

Enameled cast-iron cookware was developed in the 1920s. In 1934, the French company Cousances designed the enameled cast iron Doufeu to reduce excessive evaporation and scorching in cast iron Dutch ovens. Modeled on old braising pans in which glowing charcoal was heaped on the lids (to mimic two-fire ovens), the Doufeu has a deep recess in its lid which instead is filled with ice cubes. This keeps the lid at a lower temperature than the pot bottom. Further, little notches on the inside of the lid allow the moisture to collect and drop back into the food during the cooking. Although the Doufeu (literally, "gentlefire") can be used in an oven (without the ice, as a casserole pan), it is chiefly designed for stove top use.

Stainless steel

.jpg)

Stainless steel is an iron alloy containing a minimum of 11.5% chromium. Blends containing 18% chromium with either 8% nickel, called 18/8, or with 10% nickel, called 18/10, are commonly used for kitchen cookware. Stainless steel's virtues are resistance to corrosion, non-reactivity with either alkaline or acidic foods, and resistance to scratching and denting. Stainless steel's drawbacks for cooking use are that it is a relatively poor heat conductor and its non-magnetic property, although recent developments have allowed the production of magnetic 18/10 alloys, which thereby provides compatibility with induction cooktops, which require magnetic cookware. Since the material does not adequately spread the heat itself, stainless steel cookware is generally made as a cladding of stainless steel on both sides of an aluminum or copper core to conduct the heat across all sides, thereby reducing "hot spots", or with a disk of copper or aluminum on just the base to conduct the heat across the base, with possible "hot spots" at the sides. In so-called "tri-ply" cookware, the central aluminum layer is obviously non-magnetic, and the interior 18/10 layer need not be magnetic, but the exterior layer at the base must be magnetic to be compatible with induction cooktops. Stainless steel does not require seasoning to protect the surface from rust, but may be seasoned to provide a non-stick surface.

Carbon steel

.jpg)

Carbon-steel cookware can be rolled or hammered into relatively thin sheets of dense material, which provides robust strength and improved heat distribution. Carbon steel accommodates high, dry heat for such operations as dry searing. Carbon steel does not conduct heat efficiently, but this may be an advantage for larger vessels, such as woks and paella pans, where one portion of the pan is intentionally kept at a different temperature than the rest. Like cast iron, carbon steel must be seasoned before use, usually by rubbing a fat or oil on the cooking surface and heating the cookware on the stovetop or in the oven. With proper use and care, seasoning oils polymerize on carbon steel to form a low-tack surface, well-suited to browning, Maillard reactions and easy release of fried foods. Carbon steel will easily rust if not seasoned and should be stored seasoned to avoid rusting. Carbon steel is traditionally used for crêpe and fry pans, as well as woks.

Clad aluminium or copper

Cladding is a technique for fabricating pans with a layer of efficient heat conducting material, such as copper or aluminum, covered on the cooking surface by a non-reactive material such as stainless steel, and often covered on the exterior aspect of the pan ("dual-clad") as well. Some pans feature a copper or aluminum interface layer that extends over the entire pan rather than just a heat-distributing disk on the base. Generally, the thicker the interface layer, especially in the base of the pan, the more improved the heat distribution. Claims of thermal efficiency improvements are, however, controversial, owing in particular to the limiting and heat-banking effect of stainless steel on thermal flows.

Aluminum is typically clad on both the inside and the exterior pan surfaces, providing both a stainless cooking surface and a stainless surface to contact the cooktop. Copper of various thicknesses is often clad on its interior surface only, leaving the more attractive copper exposed on the outside of the pan (see Copper above).

Some cookware use a dual-clad process, with a thin stainless layer on the cooking surface, a thick core of aluminum to provide structure and improved heat diffusion, and a foil layer of copper on the exterior to provide the "look" of a copper pot at a lower price.[16]

Coating

Enamel

Enameled cast iron cooking vessels are made of cast iron covered with a porcelain surface. This creates a piece that has the heat distribution and retention properties of cast iron combined with a non-reactive, low-stick surface.

The enamel over steel technique creates a piece that has the heat distribution of carbon steel and a non-reactive, low-stick surface. Such pots are much lighter than most other pots of similar size, are cheaper to make than stainless steel pots, and do not have the rust and reactivity issues of cast iron or carbon steel. Enamel over steel is ideal for large stockpots and for other large pans used mostly for water-based cooking. Because of its light weight and easy cleanup, enamel over steel is also popular for cookware used while camping.

Seasoning

Seasoning is the process of treating the surface of a cooking vessel with a dry, hard, smooth, hydrophobic coating formed from polymerized fat or oil. When seasoned surfaces are used for cookery in conjunction with oil or fat a stick-resistant effect is produced.

Some form of post-manufacturing treatment or end-user seasoning is mandatory on cast-iron cookware, which rusts rapidly when heated in the presence of available oxygen, notably from water, even small quantities such as drippings from dry meat. Food tends to stick to unseasoned iron and carbon steel cookware, both of which are seasoned for this reason as well.

Other cookware surfaces such as stainless steel or cast aluminium do not require as much protection from corrosion but seasoning is still very often employed by professional chefs to avoid sticking.

Seasoning of other cookware surfaces is generally discouraged. Non-stick enamels often crack under heat stress, and non-stick polymers (such as Teflon) degrade at high heat so neither type of surface should be seasoned.

PTFE non-stick

Steel or aluminum cooking pans can be coated with a substance such as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, often referred to with the genericized trademark Teflon) in order to minimize food sticking to the pan surface. There are advantages and disadvantages to such a coating. Coated pans are easier to clean than most non-coated pans, and require little or no additional oil or fat to prevent sticking, a property that helps to produce lower fat food. On the other hand, some sticking is required to cause sucs to form, so a non-stick pan cannot be used where a pan sauce is desired. Non-stick coatings tend to degrade over time and are susceptible to damage. Using metal implements, harsh scouring pads, or chemical abrasives can damage or destroy cooking surface.

Non-stick pans must not be overheated. The coating is stable at normal cooking temperatures, even at the smoke point of most oils. However, if a non-stick pan is heated while empty its temperature may quickly exceed 260 °C (500 °F), above which the non-stick coating may begin to deteriorate, changing color and losing its non-stick properties.[17] Above 350 °C (662 °F), the non-stick coating will rapidly decompose and emit toxic fumes, which are especially dangerous to birds, and may cause polymer fume fever in human beings.[17][18]

Non-metallic cookware

Non-metallic cookware can be used in both conventional and microwave ovens. Non-metallic cookware typically can not be used on the stovetop, although Corningware and Pyroflam are some exceptions.

Pottery

Pottery has been used to make cookware from before dated history. Pots and pans made with this material are durable (some could last a lifetime or more) and are inert and non-reactive. Heat is also conducted evenly in this material. They can be used for both cooking in a fire pit surrounded with coals and for baking in the oven.

Ceramics

Glazed ceramics, such as porcelain, provide a nonstick cooking surface. Historically some glazes used on ceramic articles contained levels of lead, which can possess health risks; although this is not a concern with the vast majority of modern ware. Some pottery can be placed on fire directly.

Glass

Borosilicate glass is safe at oven temperatures. The clear glass also allows for the food to be seen during the cooking process. However, it cannot be used on a stovetop, as it cannot cope with stovetop temperatures.

Glass-ceramic

Glass ceramic is used to make products such as Corningware and Pyroflam, which have many of the best properties of both glass and ceramic cookware. While Pyrex can shatter if taken between extremes of temperature too rapidly, glass-ceramics can be taken directly from deep freeze to the stove top. Their very low coefficient of thermal expansion makes them less prone to thermal shock.

Stone

A natural stone can be used to diffuse heat for indirect grilling or baking, as in a baking stone or pizza stone, or the French pierrade.

Silicone

Silicone bakeware is light, flexible and able to withstand sustained temperatures of 360 °C (675 °F). It melts around 500 °C (930 °F), depending upon the fillers used. Its flexibility is advantageous in removing baked goods from the pan. This rubbery material should not to be confused with the silicone resin used to make hard, shatterproof children's dishware, which is not suitable for baking.

Types of cookware and bakeware

The size and shape of a cooking vessel is typically determined by how it will be used. Intention, application, technique and configuration also have a bearing on whether a cooking vessel is referred to as a pot or a pan. Generally within the classic batterie de cuisine a vessel designated "pot" is round, has "ear" handles in diagonal opposition, with a relatively high height to cooking surface ratio, and is intended for liquid cooking such as stewing, stocking, brewing or boiling. Vessels with a long handle or ear handles, a relatively low height to cooking surface ratio, used for frying, searing, reductions, braising and oven work take the designation "pan". Additionally, while pots are round, pans may be round, oval, squared, or irregularly shaped.

Cookware

- Braising pans and roasting pans (also known as "braisers", "roasters" or rondeau pans) are large, wide and shallow, to provide space to cook a roast (chicken, beef or pork). They typically have two loop or tab handles, and may have a cover. Roasters are usually made of heavy-gauge metal so that they may be used safely on a cooktop following roasting in an oven. Unlike most other cooking vessels, roasters are usually rectangular or oval. There is no sharp boundary between braisers and roasters – the same pan, with or without a cover, can be used for both functions. In Europe, clay roasters remain popular because they allows roasting without adding grease or liquids. This helps preserve flavor and nutrients. Having to soak the pot in water for 15 minutes before use is a notable drawback.

- Casserole pots (for making casseroles) resemble roasters and Dutch ovens, and many recipes can be used interchangeably between them. Depending on their material, casseroles can be used in ovens or on stovetops. Casseroles are often made of metal, but are popular in glazed ceramic or other vitreous material as well.

- Dilipots are long thin pots created to sanitize with boiling water.

- Dutch ovens are heavy, relatively deep pots with heavy lids, designed to re-create oven conditions on stovetops or campfires. They can be used for stews, braised meats, soups and a large variety of other dishes that benefit from low-heat, slow cooking. Dutch ovens are typically made from cast iron or natural clay and are sized by volume.

- A wonder pot, an Israeli invention, acts as a Dutch oven but is made of aluminium. It consists of three parts: an aluminium pot shaped like a Bundt pan, a hooded cover perforated with venting holes, and a thick, round, metal disc with a centre hole that is placed between the wonder pot and the flame to disperse heat.

- Frying pans, frypans or skillets provide a large flat heating surface and shallow, sloped sides, and are best for pan frying. Frypans with shallow, rolling slopes are sometimes called omelette pans. Grill pans are frypans that are ribbed, to let fat drain away from the food being cooked. Frypans and grill pans are generally sized by diameter (20–30 cm).

- Spiders are skillets with three thin legs to keep them above an open fire. Ordinary flat-bottomed skillets are also sometimes called spiders, though the term has fallen out of general use.[19]

- Griddles are flat plates of metal used for frying, grilling and making pan breads such as pancakes, injera, tortillas, chapatis and crepes. Traditional iron griddles are circular, with a semicircular hoop fixed to opposite edges of the plate and rising above it to form a central handle. Rectangular griddles that cover two stove burners are now also common, as are griddles that have a ribbed area that can be used like a grill pan. Some have multiple square metal grooves enabling the contents to have a defined pattern, similar to a waffle maker. Like frypans, round griddles are generally measured by diameter (20–30 cm).

- In Scotland, griddles are referred to as girdles. In some Spanish-speaking countries, a similar pan is referred to as a comal. Crepe pans are similar to griddles, but are usually smaller, and made of a thinner metal.

- Both griddles and frypans can be found in electric versions. These may be permanently attached to a heat source, similar to a hot plate.

| Look up saucepan in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Saucepans are round, vertical-walled vessels used for simmering or boiling. Saucepans generally have one long handle. Larger pans of similar shape with two ear handles are sometimes called "sauce-pots" or "soup pots" (3–12 litres). Saucepans and saucepots are denominated by volume (usually 1–8 l). While saucepots often resemble Dutch ovens in shape, they are generally lighter. Very small saucepans used for heating milk are referred to as "milk pans" - such saucepans usually have a lip for pouring heated milk.

- A variation on the saucepan with sloping sides is called a "Windsor", "evasee" or "fait-tout", and is used for evaporative reducing. Saucepans with rounded sides are called "sauciers" which also provide more efficient evaporation and generate a return wave when shaken. Both flared saucepan variations tend to dry or cake preparations on their walls, and are less suited to starch-thickened sauces than standard saucepans.

- Sauté pans, used for sautéing, have a large surface-area and relatively low sides to permit rapid evaporation and to allow the cook to toss the food. The word sauté comes from the French verb sauter, meaning "to jump". Sauté pans often have straight vertical sides, but may also have flared or rounded sides.

- Stockpots are large pots with sides at least as tall as their diameters. This allows stock to simmer for extended periods of time without major reducing. Stockpots are typically measured in volume (6-36 l). Stock pots come in a large variety of sizes to meet any need from cooking for a family to preparing food for a banquet. A specific type of stockpot exists for lobsters, and Hispanic cultures use an all-metal stockpot, usually called a caldero, to cook rice.[20]

- Woks are wide, roughly bowl-shaped vessels, with one or two handles at or near the rim. This shape allows a small pool of cooking oil in the centre of the wok to be heated to a high temperature using relatively little fuel, while the outer areas of the wok are used to keep food warm after it has been fried in the oil. In the Western world, woks are typically used only for stir-frying, but they can be used for anything from steaming to deep frying.

Bakeware

Bakeware is designed for use in the oven (for baking), and encompasses a variety of different styles of baking pans as cake pans, pie pans, and bread pans.

- Cake tins (or cake pans in the US) include square pans, round pans, and speciality pans such as angel food cake pans and springform pans often used for baking cheesecake. Another type of cake pan is a muffin tin, which can hold multiple smaller cakes.

- Sheet pans, cookie sheets, and Swiss roll tins are bakeware with large flat bottoms.

- Pie pans are flat-bottomed flare-sided tins specifically designed for baking pies.

A Pyrex chicken roaster

A Pyrex chicken roaster

A Passover brownie cake baked in a wonder pot

A Passover brownie cake baked in a wonder pot.jpg) Large and small skillets

Large and small skillets Electric griddle with temperature control

Electric griddle with temperature control A copper saucepot (stainless lined, with cast iron handles)

A copper saucepot (stainless lined, with cast iron handles)- Angel food cake pan

A springform pan with pizza

A springform pan with pizza

List of cookware and bakeware

- Comal (cookware)

- Cookie sheet

- Double boiler

- Doufeu

- Dutch oven

- Food processor

- Griddle (also called tava or tawa)

- Karahi

- Kazan

- Kettle

- Pans

- Baking pan

- Chip pan

- Crepe pan (also called a tava)

- Frying pan

- Roasting pan

- Saucepan (described in current article)

- Sauté pan

- Sheet pan

- Splayed Sauté pan

- Springform pan

- Tube pan [types include angel food cake pan and Bundt cake (Kugelhopf) pan]

- Pots

- Beanpot

- Cooking pot

- Stockpot

- Wonder Pot

- Pressure cooker

- Ramekin

- Roasting rack

- Saucier (described in current article)

- Soufflé dish

- Tajine

- Wok

See also

- Cauldron

- Food storage

- Gastronorm sizes (standard sizes of container)

- Kappabashi-dori

- Kitchenware

- Kitchenware brands

- List of cooking vessels

- List of food preparation utensils

- Marc Grégoire

- Multicooker

- Pot-holder

- Stoneware

- Surface chemistry of cooking

- Vacuum filler

References

- Wu, X.; Zhang, C.; Goldberg, P.; Cohen, D.; Pan, Y.; Arpin, T.; Bar-Yosef, O. (2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. PMID 22745428.

- Zielinski (6 February 2013). "Stone Age Stew? Soup Making May Be Older Than We'd Thought". NPR. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- Tannahill pg 13

- Tannahill p. 14–16

- Frank Hamilton Cushing (2005). "Online Reader - A Study of Pueblo Pottery as Illustrative of Zuñi Culture Growth. by Cushing". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Tannahill pg 16, 96

- Beard pg 174-175

- Greenfieldboyce, Nell (September 5, 2008). "Pageant Protest Sparked Bra-Burning Myth". NPR. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- Williams1986, pp. 8–9

- "Am I at risk of developing dementia?". Facts about dementia. Alzheimer's Society. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2005.

- Bondy, SC (January 2016). "Low levels of aluminum can lead to behavioral and morphological changes associated with Alzheimer's disease and age-related neurodegeneration". Neurotoxicology. 52: 222–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2015.12.002. PMID 26687397.

- Kandimalla, R; Vallamkondu, J; Corgiat, EB; Gill, KD (March 2016). "Understanding Aspects of Aluminum Exposure in Alzheimer's Disease Development". Brain Pathology (Zurich, Switzerland). 26 (2): 139–54. doi:10.1111/bpa.12333. PMID 26494454.

- "Myth 4: Drinking out of aluminum cans or cooking in aluminum pots and pans can lead to Alzheimer's disease". Alzheimer Myths. Alzheimer's Association. Retrieved June 19, 2010.

- Yegambaram, M; Manivannan, B; Beach, TG; Halden, RU (2015). "Role of environmental contaminants in the etiology of Alzheimer's disease: a review". Current Alzheimer Research. 12 (2): 116–46. doi:10.2174/1567205012666150204121719. PMC 4428475. PMID 25654508.

- Hoare, W.E. (1959). Hot Tinning (2nd ed.). Greenford, England: Tin Research Institute. p. 82.

- Williams1986, pp. 9–10

- Chemours, Key Safety Questions About Teflon™ Nonstick Coatings

- Houlihan, Thayer & Klien 2003 "...a generic non-stick frying pan preheated on a conventional, electric stovetop burner reached 736 °F in three minutes and 20 seconds..."

- Ross, Alice (20 January 2001). "Hearth to Hearth: There's History In Your Frying Pan". journalofantiques.com. The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Albala, Ken (2011). Food Cultures of the World Encyclopedia: (Four Volumes). Greenwood. ISBN 9780313376276. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

Bibliography

- Beard, James (1975). The Cooks' Catalogue. et al. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-011563-0.

- Williams, Chuck (1986). The Williams-Sonoma Cookbook and Guide to Kitchenware. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-54411-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Bridge, Fred; Tibbetts, Jean F. (1991). The Well-Tooled Kitchen. William Morrow and Company. ISBN 978-0-688-08135-5.

- Reay Tannahill (1988). Food in History. Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-517-57186-6.

.jpg)