Christianity in Turkey

Christianity in Turkey has had a long history dating back to the 1st-century AD. In modern times the percentage of Christians in Turkey has declined from 20–25 percent in 1914 to 3–5.5 percent in 1927, to 0.3–0.4% today[1][2] roughly translating to 200,000–320,000 devotees.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| est. 200,000–320,000 | |

| Religions | |

| Christianity (Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch, Syriac Orthodox Church, Protestant) | |

| Languages | |

| Greek, Ecclesiastical Latin, Koine Greek, Turkish, Armenian, Syriac, Arabic, English |

Religion in Turkey  |

|---|

| Secularism in Turkey |

|

|

|

Minor religions

|

| Irreligion in Turkey |

| Christianity by country |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Oceania

|

|

South America

|

|

|

This was due to events which had a significant impact on the country's demographic structure, such as the First World War, the genocide of Syriacs, Assyrians, Greeks, Armenians, and Chaldeans the population exchange between Greece and Turkey,[3] and the emigration of Christians (such as Assyrians, Greeks, Armenians etc.) to foreign countries (mostly in Europe and the Americas) that actually began in the late 19th century and gained pace in the first quarter of the 20th century, especially during World War I.[4][5] Today there are more than 200,000–320,000 people of different Christian denominations, representing roughly 0.3–0.4 percent of Turkey's population,[1][2] including an estimated 80,000 Oriental Orthodox,[6] 35,000 Catholics,[7] 18,000 Antiochian Greeks,[8] 5,000 Greek Orthodox[6] and 8,000 Protestants. There is also a small group of ethnic Orthodox-Christian Turks (mostly living in Istanbul or Izmir) who follow the Greek Orthodox or Syriac Orthodox church and additionally Protestant Turks who still face difficulties regarding social acceptance and also historic claims to churches or property in the country because they are from recent converts from Muslim Turkish backgrounds (rather than ethnic minorities).[9] Ethnically Turkish Protestants number around 7,000–8,000[10][11]. In 2009 there were 236 churches open for worship in Turkey.[12] The Eastern Orthodox Church has been headquartered in Constantinople since the 4th century.[13][14][9]

Historical background

Early Christianity

.jpg)

Christianization of Syriacs and Armenians most likely began around the 1st century AD.[15] The spread of Christianity beyond Jerusalem is discussed in the Book of Acts.[16]

The Cappadocian Fathers produced some of the earliest hagiographies in the region. In addition to writings about feminine virtue by Gregory of Nyssa and Gregory of Nazianzos, later texts about Nicholas of Sion and Theodore of Sykeon described miracles and rural life.[17]

Edessa was an early center of Syriac Orthodox Church, which had accepted only the first three ecumenical councils: Nicaea (325), Constantinople (381) and Ephesus (431). They were strongly opposed to Chalcedonian Creed that had been established by the Council of Chalcedon in 451. In the 5th and 6th centuries, the Oriental Orthodox Church that originated in Antioch continued to fracture into multiple denominations.[18] Some Armenian miaphysite Christians sought to reunite with Rome in later centuries, but their efforts were unsuccessful.[16]

The Eastern Orthodox Church split from Rome during the Great Schism of 1054. With the arrival of the crusaders many Orthodox bishops, particularly in Antioch, were replaced by Latin prelates. After the Mongols defeated the Abbasid Caliphate in 1258, the Armenians and Nestorians had decent relations with the conquering Il-khans for a time, but by the end of the 14th-century many Syrian Orthodox and Nestorian churches were destroyed when the Turco-Mongolian ruler Temür raided West Asia.[16]

Two out of the five centers (Patriarchates) of the ancient Pentarchy are in Turkey: Constantinople (Istanbul) and Antioch (Antakya). Antioch was also the place where the followers of Jesus were called "Christians" for the first time in history, as well as being the site of one of the earliest and oldest surviving churches, established by Saint Peter himself. For a thousand years, the Hagia Sophia was the largest church in the world.

Turkey is also home to the Seven Churches of Asia, where the Revelation to John was sent. Apostle John is reputed to have taken Virgin Mary to Ephesus in western Turkey, where she spent the last days of her life in a small house, known as the House of the Virgin Mary, which still survives today and has been recognized as a holy site for pilgrimage by the Catholic and Orthodox churches, as well as being a Muslim shrine. The cave of the Seven Sleepers is also located in Ephesus.

The death of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste (modern day Sivas) is recorded as 320 AD during a persecution by Emperor Licinius. They are mentioned by Basil, Gregory of Nyssa, Ephrem the Syrian and John Chrysostom.[19]

Late Ottoman Empire

In accordance with the traditional custom at the time, Sultan Mehmed II allowed his troops and his entourage three full days of unbridled pillage and looting in the city shortly after it was captured. Once the three days passed, he would then claim its remaining contents for himself.[20][21] However, by the end of the first day, he proclaimed that the looting should cease as he felt profound sadness when he toured the looted and enslaved city.[22][20] Hagia Sophia was not exempted from the pillage and looting and specifically became its focal point as the invaders believed it to contain the greatest treasures and valuables of the city.[23] Shortly after the defence of the Walls of Constantinople collapsed and the Ottoman troops entered the city victoriously, the pillagers and looters made their way to the Hagia Sophia and battered down its doors before storming in.[24]

Throughout the period of the siege of Constantinople, the trapped worshippers of the city participated in the Divine Liturgy and the Prayer of the Hours at the Hagia Sophia and the church formed a safe-haven and a refuge for many of those who were unable to contribute to the city's defence, which comprised women, children, elderly, the sick and the wounded.[25][26] Being trapped in the church, the many congregants and yet more refugees inside became spoils-of-war to be divided amongst the triumphant invaders. The building was desecrated and looted, with the helpless occupants who sought shelter within the church being enslaved.[23] While most of the elderly and the infirm/wounded and sick were killed, and the remainder (mainly teenage males and young boys) were chained up and sold into slavery.[27]

Anglican, American Presbyterian and German Lutheran missionaries arrived in the Ottoman Empire in the 19th-century.[16]

In the 19th century, there were nationalistic campaigns against Assyrians which often had the assistance of Kurdish paramilitary support. In 1915, Turks and Kurds massacred tens of thousands Assyrians in Siirt. Assyrians were attacked in the Hakkari mountains by the Turkish army with the help of Kurdish tribes, and many Christians were deported and about a quarter million Assyrians were murdered or died due to persecution. This number doubles if the killings during the 1890s are included.[28] Kurds saw the Assyrians as dangerous foreigners and enforcers of the British colonizers, which made it justifiable to them to commit ethnic cleansing. The Kurds fought the Assyrians also due to fears that the Armenians, or European colonial powers backing them, would assume control in Anatolia.[29] Kurdish military plundered Armenian and other Christian villages.[29]

In the 1890s the Hamidiye (Kurdish paramilitary units) attacked Armenians in a series of clashes that culminated in the pogroms of 1894–1896 and the Adana massacre in 1909. It is estimated that between 80,000 and 300,000 Armenians were killed during these pre-War massacres.[15][30][31][32]

First World War

During the tumultuous period of the first world war, up to 3 million indigenous Christians are alleged to have been killed. Prior to this time, the Christian population stood at around 20% -25% of the total. According to professor Martin van Bruinessen, relations between Christians and Kurdish and other Muslim peoples were often bitter and during World War I "Christians of Tur Abdin (in Turkey) for instance have been subjected to brutal treatment by Kurdish tribes, who took their land and even their daughters".[33]

Kurdish-dominated Hamidiye slaughtered Christian Armenians in Tur Abdin region in 1915.[34] It is estimated that ten thousand Assyrians were killed, and reportedly "the skulls of small children were smashed with rocks, the bodies of girls and women who resisted rape were chopped into pieces live, men were mostly beheaded, and the clergy skinned or burnt alive...." [34] In 1915, Turks and Kurds plundered the Assyrian village of Mar-Zaya in Jelu and slaughtered the population, it is estimated that 7,000 Assyrians were slaughtered during this period. In September 1914 more than 30 Armenian and Assyrian villages were burnt by Kurdish and Turkish mobs in the Urmia region.[34] After the Russian army retreated, Turkish troops with Kurdish detachments organized mass slaughters of Assyrians, in the Assyrian village of Haftvan 750 men were beheaded and 5000 assyrian women were taken to kurdish harems.[34] Turks and Kurds also slaughtered Christians in Diarbekir. There was a policy during the Hamidian era to use Kurdish tribes as irregulars (Hamidiye units) against the Armenians.[34][35][36][37]

Treaty of Lausanne

The Greek forces who occupied Smyrna in the post-war period were defeated in the Turkish War of Independence which ended with the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne. Under the terms of the peace treaty, 1.3 million Christian residents of Turkey were relocated to Greece and around 400,000 Muslims were likewise moved from Greece to Turkey. When the Turkish state was founded in 1923 the remaining Greek population was estimated to be around 111,000; the Greek Orthodox communities in Istanbul, Gökçeada, and Bozcaada numbering 270,000 were exempted. Other terms of the treaty included various provisions to protect the rights of religious minorities and a concession by the Turks to allow the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate to remain in Istanbul.[38]

Modern Turkey

.jpg)

The BBC reported in 2014 that Turkey's Christian population had declined from 20% to 0.2% since 1914.[39]

The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) designated Turkey a "Country of Particular Concern" for religious freedom, noting “systematic limitations on the freedom of religion or belief” with respect to access to places of worship, religious education and right to train clergy. The report does note some areas of improvement such as better protection of the property rights of non-Muslims.[40]

In the pre-war period American missionaries had been actively involved in the Ottoman education system. Many of the schools were closed down and suffered under stringent regulations and burdensome taxes during the country's secularization. Historically, these schools had worked with the Ottoman Empire's Christian communities, and were regarded with suspicion by the fledgling state. One contemporary account noted that "If American opinion has been uninformed, misinformed and prejudiced, the missionaries are largely to blame. Interpreting history in terms of the advance of Christianity, they have given an inadequate, distorted, and occasionally grotesque picture of Moslems and Islam."[41]

A number of high-profile incidents targeting non-Muslims, including Christians, have occurred since the modern Turkish Republic was founded in 1923. During the Istanbul pogrom of 1955, non-Muslims (pejoratively called gayrimüslim) were attacked, harassed and killed by Turkish Muslims. In 2007, one German Protestant and two Turkish converts were tortured to death in Malatya by five men in the Zirve Publishing House murders. Turkish media called these killings the "missionary massacres".[42][43]

In 2001, Turkey's National Security Council reported that it considers Protestant missionaries the third largest threat to Turkey's national security, surpassed only by Islamic fundamentalism and the Kurdish separatist organization PKK. A 2004 report by the Turkish Armed Forces (TAF) similarly recommended implementing new laws to curb missionary activity. According to the Turkish Evangelical Churches movement, Turkish Protestant churches had only 3,000 members in 2009—about half of these were converts from Islam, while the others were Armenian and Syriac Christians.[44] Since Turkish nationality was often perceived exclusively as a Muslim identity after the Balkan Wars, the influence of Protestant missionaries on Turkey's Alevi population has been a concern since the era of Committee of Union and Progress rule.[44][45] In 2016 the Association of Protestant Churches in Turkey released a report warning of an increase in anti-Christian hate speech.[46]

Turkey's Christian community has been largely non-disruptive, with the notable exception of one convert, who hijacked Turkish Airlines Flight 1476 with the stated intent of flying it to the Vatican to meet the Pope and ask for his help to avoid serving in a "Muslim army".[47]

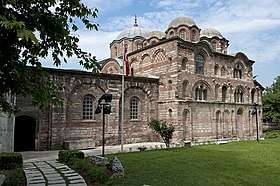

In 2013, the Washington Post reported that members of the ruling Ak Parti had expressed their desires to convert Hagia Sophia into a mosque. Hagia Sophia, which is called ayasofya in Turkish, is an ancient church dating to 360 AD that was converted into a mosque after Mehmed II conquered Constantinople in 1453. It has been a museum since 1935. Patriarch Bartholomew objected to the government's rhetoric, saying "If it is to reopen as a house of worship, then it should open as a Christian church.”[48] Also in 2013, the government announced that the 5th-century Monastery of Stoudios, located in Istanbul's Samatya neighborhood, would be converted into a mosque. The monastery, one of Byzantium's most important, was sacked during the Crusades and later served as a mosque for a time, until it was converted to a museum during the 20th-century.[49][50][51]

There is ethnic Turkish Protestant Christian community in Turkey which number about 7,000–8,000[11][10] adherents most of them came from Muslim Turkish background.[52][53][54]

Today the Christian population of Turkey is estimated at around 200,000- 320,000 Christians.[6][55] 35,000 Catholics of varying ethnicities, 25,000 ethnic Assyrians, (mostly followers of the Assyrian Church of the East, Syriac Orthodox Church and Chaldean Catholic Church),[56] up to 22,000 Greeks (3,000–4,000 Greek Orthodox,[55] 15,000–18,000 Antiochian Greeks[57][57][58]) and smaller numbers of Bulgarians, Georgians, and Protestants of various ethnicities.

According to Bekir Bozdağ, Deputy Prime Minister of Turkey, there were 349 active churches in Turkey in October 2012: 140 Greek, 58 Assyrian and 52 Armenian.[59]

In 2015 the Turkish government gave permission for the Christian channel SAT-7 to broadcast on the government-regulated Türksat satellite.[60]

Christian communities

By the 21st-century, Turkey's Greek Orthodox population had declined to only around 2,000–3,000.[38] There are between 40,000 and 70,000 Christian Armenian citizens of Turkey.[15]

The largest Christian population in Turkey is in Istanbul, which has a large community of Armenians and Greeks. Istanbul is also where the Patriarchate of Greek Orthodox Christianity is located. Antioch, located in Turkey's Hatay province, is the original seat of the namesake Antiochian Orthodox Church, but is now the titular see. The area, known for having ethnic diversity and large Christian community, has 7,000 Christians and 14 active churches. The city has one of the oldest churches in the world as well, called the Church of St Peter, which is said to have been founded by the Saint himself.[61]

Tur Abdin is a large area with a multitude of mostly Syriac Orthodox churches, monasteries and ruins. Settlements in Tur Abdin include Midyat. The Christian community in Midyat is supplemented by a refugee community from Syria and has four operating churches.[62] Some of the most significant Syriac churches and monasteries in existence are in or near Midyat including Mor Gabriel Monastery and the Saffron Monastery.

The Syriac Orthodox Church has a strong presence in Mardin. Many Syriacs left during the genocides in 1915.[63]

By some estimates, in the early 2000s there were between 10,000 and 20,000 Catholics and Protestants in Turkey.[64]

Churches in Turkey

Anglican Church

The Anglicans in Turkey form part of the Eastern Archdeaconry of the Diocese of Gibraltar in Europe. In 2008 the Bishop of Europe, Geoffrey Rowell, caused controversy by ordaining a local man to minister to Turkish-speaking Anglicans in Istanbul.[65]

Autocephalous Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate

The Autocephalous Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate (Turkish: Bağımsız Türk Ortodoks Patrikhanesi), also referred to as the Turkish Orthodox Church is unrecognized Orthodox Christian denomination.

Armenian Apostolic Church

The Armenian Apostolic Church traces its origins to St. Gregory the Illuminator who is credited with having introduced the Armenian king Tiridates III to Christianity. It is one of the most ancient churches. Historically, the Armenian Church accepted only the first three Ecumenical Councils, rejecting the Council of Chalcedon in 451; its Christology is sometimes described as "non-Chalcedonian" for this reason. The Bible was first translated into the Armenian language by St. Mashtos.[66][64]

Turkey's Armenian Christian community is led by the Armenian Patriarchates of Istanbul and Jerusalem. As of 2008 estimates of Turkey's Armenian Orthodox population range from between 50,000 and 70,000.[64]

There are 35 churches maintained by the religious foundation in Istanbul and its surrounding areas. Besides Surp Asdvadzadzin Patriarchal Church (translation: the Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Patriarchal Church) in Kumkapi, Istanbul, there are tens of Armenian Apostolic churches. There are other churches in Kayseri, Diyarbakır, Derik, İskenderun, and Vakifli Koyu that are claimed by foundations as well. Around 1,000 Armenian churches throughout Turkey sit on public or privately owned land as well, with them all either being re-purposed or abandoned and/or in ruins.

- Armenian Catholic Church- there are several Armenian Catholic churches in Istanbul, including a large cemetery. In Mardin one remains as a Museum and occasional religious center.

- Armenian Evangelical Church- The Armenian Protestants have three churches in Istanbul from the 19th century.[67]

Greek Orthodox Church

Constantinople became established in the ecclesiastical hierarchy at the Council of Constantinople in 381. The legendary origins of the Patriarchate of Constantinople go back to St. Andrew, Metrophanes and Alexander of Constantinople. Constantinople's primacy over the Patriarchates of Alexandria and Antioch was reaffirmed at the Council of Chalcedon in 481, after which the papacy in Rome supported Constantinople in its dispute with Alexandria over monophysitism. Later, when Rome sought to assert its primacy over Byzantium, the Eastern Orthodox church developed the doctrine of pentarchy as a response.[68]

During the 8th and 9th centuries, Byzantium was embroiled in the Iconoclastic persecution.[69] The Photian schism was also 9th century power struggle for the Patriarchate between Ignatios, backed by Pope Nicholas I, and Photios I of Constantinople.[70][71]

The Byzantine rite is similar to mass in the Catholic Church and the Divine Office (cycle of eight non-Mass services in the Catholic faith).[72] In addition to the Hours of the Office, the Byzantine rite is used for sacraments (including marriage and baptism), ordination, funerals, blessings and other occasions.[73] The three divine liturgies of the Byzantine rite are John Chrysostom’s, Basil’s, and the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts.[73]

Antioch is the official seat of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East. Hatay Province including Antakya is not part of the canonic area of the Church of Constantinople. Most of the local orthodox persons are Arabic-speaking.

- Turkish Orthodox Church (unrecognized by all other churches in the world) was created by Turkish nationalists who tried to create a Turkish national church to counter the influence of the Ecumenical Patriarchate for political reasons.

Catholic churches

Though the Armenian Apostolic Church was no longer in union with Rome and Byzantium after the Council of Chalcedon, a number of Armenians have converted to Catholicism over the years. After the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II extended formal recognition to Catholics, an Armenian Catholic Patriarchate was established in Constantinople.[74][75]

- Vicariate Apostolic of Istanbul

- Cathedral: Cathedral of the Holy Spirit, Istanbul

- Basilica: St. Anthony of Padua Church in Istanbul, Istanbul

- Vicariate Apostolic of Anatolia

- Cathedral: Cathedral of the Annunciation, İskenderun, İskenderun

- Co-cathedral: Co-Cathedral of St. Anthony of Padua, Mersin, Mersin

- Archdiocese of Izmir

- Cathedral: St. John's Cathedral, Izmir, Izmir

- Archeparchy of Istanbul (Armenian)

- Archeparchy of Diyarbakir (Chaldaean)

- Vicariate Apostolic of Istanbul (Byzantine)

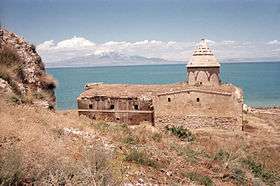

- Church of St Peter of Antakya

- Church: Church of St Peter

Evangelical churches

The Armenian Evangelical Church was founded in 1846, after Patriarch Matteos Chouhajian excommunicated members of the "Pietisical Union" who had started to raise questions about possible conflicts between scripture and Church traditions.[74] The new church was recognized by the Ottoman government in 1850 after encouragement from the British Ambassador Henry Wellesley Cowley.[76] There were reportedly 15 Turkish converts in Constantinople in 1864. One church minister said "We wanted the Turks first to become Armenian". Hagop A. Chakmakjian commented that "the implication was that to be Christian meant to be identified with the Armenian people".[77]

Churches of the West Syriac Rite

The Christian population of the West Syriac Rite probably has the most regional influence in Turkey, as its population was not confined to or was centered in Istanbul like the rest of the Christian communities of Turkey were. Active churches are located in Istanbul, Diyarbakir, Adiyaman, and Elazig.[78] There are many both active and inactive churches in the traditionally Neo-Aramaic area of Tur Abdin, which is a region centered in the western area of(Mardin province, and has areas that go into Sirnak, and Batman Province. Up until the 1980s the Syriac population was concentrated there as well, but a large amount of the population has fled the region to Istanbul or abroad due to the Kurdish-Turkish conflict (1978-present). The Church structure is still organized however, with 12 reverends stationed in churches and monasteries there.[79] Churches were also in several other provinces as well, but in the Assyrian Genocide the churches in those provinces were destroyed or left ruined.

Churches of the West Syriac Rite include:

Churches of the East Syriac Rite

The Nestorian (Church of the East) church in Turkey was completely wiped out in the Assyrian Genocide, although they were originally centered in Hakkari. The Chaldean Branch is based primarily in Istanbul, although its church structure is centered in Diyarbakir.

Churches of the East Syriac Rite include:

The main churches are at Ankara (St Nicholas), Istanbul (Christ Church) and Izmir (St John the Evangelist).

Other denominations

The Armenian Protestants own three Istanbul churches from the 19th century.[80] There is an Alliance of Protestant Churches in Turkey.[81]

There are churches for foreigners in compounds and resorts, although they are not counted in lists of churches as they are used only by tourists and expatriots.

List of church buildings in Turkey

Churches of the Armenian rite

| Church name | Picture | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Church of the Apparition of the Holy Cross (Kuruçeşme, Istanbul) Yerevman Surp Haç Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Archangels Armenian Church (Balat, Istanbul) Surp Hıreşdagabed Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Cross Armenian Church (Kartal, Istanbul) Surp Nişan Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Cross Armenian Church (Üskudar, Istanbul) Surp Haç Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Hripsimiants Virgins Armenian Church (Büyükdere, Istanbul) Surp Hripsimyants Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Apostolic Church (Bakırköy, Istanbul) Surp Asdvadzadzin Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Church (Beşiktaş, Istanbul) Surp Asdvadzadzin Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Church (Eyüp, Istanbul) Surp Asdvadzadzin Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Church (Ortaköy, Istanbul) Surp Asdvadzadzin Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Mother-of-God Armenian Church (Yeniköy, Istanbul) Surp Asdvadzadzin Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Resurrection Armenian Church (Kumkapı, Istanbul) Surp Harutyun Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Resurrection Armenian Church (Taksim, Istanbul) Surp Harutyun Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Three Youths Armenian Church (Boyacıköy, Istanbul) Surp Yerits Mangants Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Trinity Armenian Church (Galatasaray, Istanbul) Surp Yerrortutyun Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Narlıkapı Armenian Apostolic Church (Narlıkapı, Istanbul) Surp Hovhannes Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Elijah The Prophet Armenian Church (Eyüp, Istanbul) Surp Yeğya Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Garabed Armenian Church (Üsküdar, Istanbul) Surp Garabet Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. John the Baptist Armenian Church (Uskudar) | unknown | |

| St. John The Evangelist Armenian Church (Gedikpaşa, Istanbul) Surp Hovhannes Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. George (Sourp Kevork) Armenian Church (Samatya, Istanbul) | unknown | |

| St. Gregory The Enlightener Armenian Church (Galata, Istanbul) | active | |

| St. Gregory The Enlightener Armenian Church (Kuzguncuk, Istanbul) Surp Krikor Lusaroviç Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Gregory The Enlightener Armenian Church (Karaköy, Istanbul) Surp Krikor Lusavoriç Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Gregory The Enlightener (Kınalıada, Istanbul)Armenial Church Surp Krikor Lusavoriç Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| [[St. James Armenian Church (Altımermer, Istanbul)]] Surp Hagop Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Nicholas Armenian Church (Beykoz, Istanbul) Surp Nigoğayos Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Nicholas Armenian Church (Topkapı, Istanbul) Surp Nigoğayos Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Santoukht Armenian Church (Rumelihisarı, Istanbul) Surp Santuht Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Saviour Armenian Chapel (Yedikule, Istanbul) Surp Pırgiç Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Sergius Armenian Chapel (Balıklı, Istanbul) Surp Sarkis Anıt Mezar Şapeli | active | |

| St. Stephen Armenian Church (Karaköy, Istanbul) Surp Istepanos Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Stephen Armenian Church (Yeşilköy, Istanbul) Surp Istepanos Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Takavor Armenian Apostolic Church (Kadıkoy, Istanbul) Surp Takavor Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Saints Thaddeus and Barholomew Armenian Church (Yenikapı, Istanbul) Surp Tateos Partoğomeos Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Vartanants Armenian Church (Feriköy, Istanbul) Surp Vartanants Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| The Twelve Holy Apostles Armenian Church (Kandilli, Istanbul) Surp Yergodasan Arakelots Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| Holy Forty Martyrs of Sebastea Armenian Church (Iskenderun, Hatay) Surp Karasun Manuk Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. George Armenian Church (Derik, Mardin) Surp Kevork Ermeni Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Gregory The Enlightener Armenian Church (Kayseri) Surp Krikor Lusavoriç Ermeni Kilisesi | services held once or twice a year | |

| St. Gregory The Enligtener Armenian Church (Kırıkhan, Hatay) Surp Krikor Lusavoriç Kilisesi | active | |

| St. Giragos Armenian Church (Diyarbakır) Surp Giragos Ermeni Kilisesi | closed – confiscated by the Turkish State | |

| Cathedral of Ani |  | abandoned following 1319 earthquake |

| Cathedral of Kars | converted into a mosque | |

| Cathedral of Mren |  | ruins |

| Holy Apostles Monastery | .png) | ruins |

| Horomos |  | ruins |

| Karmravank (Vaspurakan) | ruins | |

| Kaymaklı Monastery | ruins | |

| Khtzkonk Monastery | ruins | |

| Ktuts monastery |  | abandoned |

| Varagavank | ruins, protected | |

| Narekavank |  | destroyed, mosque built on the site |

| Saint Bartholomew Monastery | ruins | |

| Saint Karapet Monastery |  |

destroyed, village built on the site |

| St. Marineh Church, Mush | ruins | |

| St. Stepanos Church | destroyed | |

| Tekor Basilica |  | destroyed |

| Armenian church in Vakıflı Vakıflıköy Ermeni Kilisesi |  | active |

Churches of the Byzantine rite

| Church name | Picture | Status |

|---|---|---|

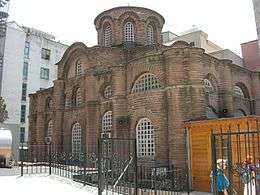

| Saint Andrew in Krisei |  | converted into a mosque |

| Chora Church |  | museum |

| Church of Christ Pantokrator (Constantinople) |  | converted into a mosque |

| Church of Christ Pantepoptes (Constantinople) |  | converted into a mosque |

| Palace of Antiochos | ruins | |

| Church of the Virgin of the Pharos | ruins | |

| Monastery of Gastria |  | converted into a mosque |

| Church of St. George, Istanbul | active | |

| Hagia Irene |  | museum |

| Hagia Sophia |  | converted into a mosque, museum |

| Church of the Holy Apostles | demolished, Fatih Mosque built on top | |

| Church of Saint John the Baptist at Lips (Constantinople) |  | converted into a mosque |

| Monastery of Stoudios | _Monastery.jpg) | ruins; closed to visitors; due to be converted into a mosque |

| Church of Saint John the Baptist en to Trullo (Constantinople) |  | converted into a mosque |

| Church of St. Mary of Blachernae (Istanbul) |  | active |

| Church of St. Mary of the Mongols |  | active |

| Myrelaion |  | converted into a mosque |

| Church of Saint Nicholas of the Caffariotes (Istanbul) |  | converted into a mosque |

| Pammakaristos Church | converted into a mosque | |

| Church of Sergius and Bacchus |  | converted into a mosque |

| Bulgarian St. Stephen Church |  | active |

| St. Demetrius Church in Feriköy, Istanbul | active | |

| Church of Hagia Thekla tu Palatiu ton Blakhernon |  | converted into a mosque |

| Church of Hagios Theodoros (Constantinople) |  | converted into a mosque |

| Church of Hagias Theodosias en tois Dexiokratus |  | converted into a mosque |

| Church of the Theotokos Kyriotissa (Constantinople) |  | converted into a mosque |

| Kuştul Monastery |  |

ruins |

| Sümela Monastery | museum | |

| House of the Virgin Mary |  | museum |

| Meryem Ana Church | active | |

| Church of St Nicholas of Myra(Santa Claus) (Demre) |  | ruins,museum |

| Bodrum Aya Nikola Church[TR] | .jpg) |

ruins |

| İskenderun St. Nicholas Church[82] |  |

active |

| Mersin Orthodox Church |  |

active |

Catholic churches

| Church name | Picture | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Cathedral of the Holy Spirit, Istanbul |  | active |

| St. Anthony of Padua Church in Istanbul |  | active |

| Cathedral of the Annunciation, İskenderun | active | |

| Church of St. Anthony, Mersin | .jpg) | active |

| St. John's Cathedral, Izmir | active | |

| Church of St Peter | museum | |

| Church of San Domenico (Constantinople) | converted into a mosque | |

| Church of SS Peter and Paul, Istanbul | active | |

| Church of Saint Benoit, Istanbul |  |

active |

| Church of St. Mary Draperis, Istanbul |  |

active |

| Saint Paul Church, Adana |  |

active |

| St. Mary's Church, İzmir |  |

active |

| St. Térèse Church, Ankara |  |

active |

| St. George's Catholic Church |  |

active[83] |

| Notre-Dame de L’Assomption, İstanbul |  |

active |

Churches of the Georgian rite

| Church name | Picture | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Our Lady of Lourdes Church, Istanbul (Bomonti Gürcü Katolik Kilisesi) |  | active |

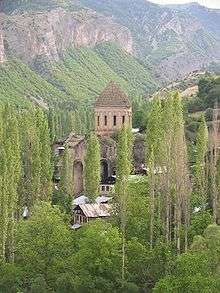

| Oshki (Öşki Manastırı/Öşk Vank/Çamlıyamaç) |  | abandoned |

| Khakhuli Monastery (Haho/Bağbaşı) |  | converted into a mosque |

| Doliskana (Dolishane/Hamamlıköy) |  | converted into a mosque |

| Bana cathedral (Penek) |  | ruins |

| Tbeti Monastery (Cevizli) |  | ruins |

| old Georgian Church, Ani |  | ruins |

| Ishkhani (İşhan) |  | protected

(since 1987)[85] |

| Parkhali (Barhal/Altıparmak) |  | protected[86] |

| Khandzta | ruins | |

| Ekeki | .jpg) | ruins |

| Otkhta Eklesia (Dörtkilise) |  | abandoned |

| Parekhi |  | ruins |

| Makriali St. George church, Kemalpaşa, Artvin | ruins | |

| St. Barlaam Monastery (Barlaham Manastırı), Yayladağı |  | ruins |

| Ancha monastery |  | ruins |

| Okhvame, Ardeşen |  | ruins |

| Tskarostavi monastery |  | ruins |

| Opiza |  | ruins |

Protestant churches

Anglican churches

| Church name | Picture | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Christ Church, Istanbul |  | active |

| St. John the Evangelist's Anglican Church, Izmir |  | active |

Other

| Church name | Picture | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Buca Protestant Baptist Church[TR] |  | active |

| Kreuzkirche, İstanbul[DE] | active | |

| Samsun Protestant Church |  |

active |

| Church of the Resurrection, İzmir |  |

active |

| All Saints' Church, Moda | active |

Churches of the Syriac rite

| Church name | Picture | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Mor Sharbel Syriac Orthodox church in Midyat |  | active |

| Mor Gabriel Monastery |  | active |

| Mor Hananyo Monastery |  | active |

See also

- Christianity in the Ottoman Empire

- Eastern Orthodoxy in Turkey

- Freedom of religion in Turkey

- Karamanlides, a Greek Orthodox, Turkish-speaking people

- Religious minorities in Turkey

- Nestorian rebellion

References

- "The Global Religious Landscape". ResearchGate. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- "Religions". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- Chapter The refugees question in Greece (1821–1930) in "Θέματα Νεοελληνικής Ιστορίας", ΟΕΔΒ ("Topics from Modern Greek History"). 8th edition (PDF). Nikolaos Andriotis. 2008.

- "'Editors' Introduction: Why a Special Issue?: Disappearing Christians of the Middle East" (PDF). Editors' Introduction. 2001. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- Içduygu, Ahmet; Toktas, Şule; Ali Soner, B. (February 1, 2008). "The politics of population in a nation-building process: emigration of non-Muslims from Turkey". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 31 (2): 358–389. doi:10.1080/01419870701491937.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey". Today's Zaman. December 15, 2008. Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- "Statistics by Country". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Archived from the original on December 18, 2016. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- "Christen in der islamischen Welt – Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte" (PDF). 2008. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- "Turkish Protestants still face "long path" to religious freedom". www.christiancentury.org. Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "International Institute for Religious Freedom: Single Post". Iirf.eu. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane Alexander (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion. 11: 17. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- "Life, Culture, Religion". Official Tourism Portal of Turkey. April 15, 2009. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- William G. Rusch (2013). The Witness of Bartholomew I, Ecumenical Patriarch. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8028-6717-9.

Constantinople has been the seat of an archiepiscopal see since the fourth century; its ruling hierarch has had the title of"Ecumenical Patriarch" ...

- Erwin Fahlbusch; Geoffrey William Bromiley (2001). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 978-90-04-11695-5.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople is the ranking church within the communion of ... Between the 4th and 15th centuries, the activities of the patriarchate took place within the context of an empire that not only was ...

- Bardakci, Mehmet; Freyberg-Inan, Annette; Giesel, Christoph; Leisse, Olaf (January 24, 2017). Religious Minorities in Turkey: Alevi, Armenians, and Syriacs and the Struggle to Desecuritize Religious Freedom. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-27026-9.

- Teule, Herman G. B. (July 10, 2014). "Christianity in Western Asia". The Oxford Handbook of Christianity in Asia. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199329069.013.0001. ISBN 9780199329069. Archived from the original on June 5, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- Talbot, Alice-Mary (October 23, 2008). "Hagiography". The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199252466.013.0082. Archived from the original on June 2, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- Kurian, George Thomas; Lamport, Mark A. (November 10, 2016). Encyclopedia of Christianity in the United States. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-4432-0.

- Farmer, David Hugh (April 14, 2011). Forty Martyrs of Sebaste – Oxford Reference. ISBN 9780199596607. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- Runciman, Steven (1965). The Fall of Constantinople 1453. Cambridge University Press. pp. 145–148. ISBN 978-0-521-39832-9.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (1979). The End of the Byzantine Empire. London: Edward Arnold. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-7131-6250-9.

- Inalcik, Halil (1969). "The Policy of Mehmed II toward the Greek Population of Istanbul and the Byzantine Buildings of the City". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 23/24: 229–249. doi:10.2307/1291293. ISSN 0070-7546.

- Nicol. The End of the Byzantine Empire, p. 90.

- Runciman, Steven (1965). The Fall of Constantinople 1453. Cambridge University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-521-39832-9.

- Runciman. The Fall of Constantinople, pp. 133–34.

- Nicol, Donald M. The Last Centuries of Byzantium 1261–1453. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972, p. 389.

- Runciman, Steven (1965). The Fall of Constantinople 1453. Cambridge University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-521-39832-9.

- Hannibal Travis, “The Assyrian Genocide, a Tale of Oblivion and Denial,” Forgotten Genocides, Oblivion, Denial, and Memory, ed. René Lemarchand (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011).""; and https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file?accession=akron1464911392&disposition=inline Archived January 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine ""THE SIMELE MASSACRE AS A CAUSE OF IRAQI NATIONALISM: HOW AN ASSYRIAN GENOCIDE CREATED IRAQI MARTIAL NATIONALISM ""

- Klein, The Margins of Empire, and https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file?accession=akron1464911392&disposition=inline Archived January 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine ""THE SIMELE MASSACRE AS A CAUSE OF IRAQI NATIONALISM: HOW AN ASSYRIAN GENOCIDE CREATED IRAQI MARTIAL NATIONALISM "

- The Hamidiye frequently attacked Christian Armenians. Alan Palmer: Verfall und Untergang des Osmanischen Reiches. Heyne, München 1994, ISBN 3-453-11768-9. (engl. Original: London 1992). The Hamidiye also played an infamous role in the massacres against Armenians in 1894–96. Martin van Bruinessen: Agha, Scheich und Staat – Politik und Gesellschaft Kurdistans. Ed. Parabolis, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-88402-259-8. Martin van Bruinessen: Agha, Shaikh and state.

- After Armenians revolted against an oppressing tax system that favoured the Kurds, the Hamidiye suppressed the revolts with massacres, which the British blamed on the Ottoman regime (even though the initiative came from local militia). (SeS) Stanford J. Shaw, Ezel Kural Shaw: History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Volume 2: Reform, Revolution, and Republic: The Rise of Modern Turkey 1808–1975. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 1977. Alan Palmer: Verfall und Untergang des Osmanischen Reiches. Heyne, München 1994, ISBN 3-453-11768-9. (engl. Original: London 1992)

- In 1895, "the massacres of the Assyrians, genocidal by nature were continuing"... where mass slaughters reached unprecedented levels. "The Assyrian villages and towns were sacked by organized mobs or by Kurdish bands. Tens of thousands were driven from their homes. About 100 thousand Assyrian population of 245 villages forcibly converted to Islam. Their property was plundered. Thousands of Assyrian women and girls were forced into Turkish and Kurdish harems. The massacres were perpetrated as barbarously as possible." Sargizov Lev, Druzhba idushchaya iz glubini vekov (Assiriytsi v Armenii) [A Friendship Coming from the Ancient Times (The Assyrians in Armenia)] (Atra, # 4, St. Petersburg, 1992, 71).

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 9, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies, Richard G. Hovannisian, Transaction Publishers

- In 1915, large numbers of Armenians were massacred by Kurdish militia and Turkish soldiers. Martin van Bruinessen: Agha, Shaikh and state, page 25, 271

- On October 3, 1914, Russian vice–Consul in Urmia Vedenski visited Assyrian villages which were already ruined by Kurds and Turks. He wrote: “The consequences of jihad are everywhere. In one village I saw burnt corpses of Assyrians with big sharp stakes in their bellies. The Assyrian houses are burnt and destroyed. The fire is still burning in the neighboring villages”. Sargizov Lev, Assiriytsi stran Blizhnego i Srednego Vostoka [The Assyrians of the Near and Middle East] (Yerevan, 1979), p. 25–26. The retreat of the Russian army from Urmia in January 1915 had tragic consequences for Assyrians. Turkish troops along with Kurdish detachments organized mass slaughter of the Assyrian population. Only 25,000 people managed to escape death. Yohannan Abraham, The Death of a Nation (New York and London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1916), p. 120.

- Reports reaching Washington indicate that "about 500,000 Armenians have been slaughtered or lost their lives... During the exodus of Armenians across the deserts they have been fallen upon by Kurds and slaughtered, but some of the Armenian women and girls, in considerable numbers, have been carried off into captivity by the Kurds. The New York Times (September 24, 1915)

- Arat, Zehra F. Kabasakal (January 1, 2011). "4. The Human Rights Condition of the Orthodox Rum". Human Rights in Turkey. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0114-7. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- "Turkey's declining Christianity". BBC News. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- "Turkey, key U.S. ally, cited for religious freedom woes". Washington Post. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- Trask, Roger R. (October 1, 2013). ""Unnamed Christianity": The American Educational Effort". The United States Response to Turkish Nationalism and Reform, 1914-1939. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-299-94386-5. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- King, Laura (April 19, 2007). "3 men slain at Bible publishing firm in Turkey". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on October 9, 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- Großbongardt, Annette (April 23, 2007). "After the Missionary Massacre: Christian Converts Live In Fear in Intolerant Turkey". Spiegel Online. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- Özyürek, Esra (January 2009). "Convert Alert: German Muslims and Turkish Christians as Threats to Security in the New Europe". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 51 (1): 91–116. doi:10.1017/S001041750900005X.

- Tambar, Kabir (April 16, 2014). "3. Anatolian Modern". The Reckoning of Pluralism: Political Belonging and the Demands of History in Turkey. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-9118-2. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- "Christians in Turkey subjected to rising hate speech: Protestant Church report". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on November 29, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- "Turkish Christian convert hijacked plane to meet Pope". The Sydney Morning Herald. October 5, 2006. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- "Turkish leaders want to convert the Hagia Sophia back into a mosque". Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 16, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- "Some Turkish Churches Get Makeovers — As Mosques". NPR.org. Archived from the original on December 6, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- "Bizans'ın en büyük manastırı cami oluyor". Radikal. Archived from the original on November 25, 2013. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- Bilotta, Emilio; Flora, Alessandro; Lirer, Stefania; Viggiani, Carlo (May 10, 2013). Geotechnical Engineering for the Preservation of Monuments and Historic Sites. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-315-88749-4. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- Jonathan Luxmoore (March 4, 2011). "Turkish Protestants still face "long path" to religious freedom". The Christian Century. Archived from the original on September 11, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- "TURKEY – Christians in eastern Turkey worried despite church opening". Hurriyetdailynews.com. July 20, 2011. Archived from the original on September 11, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- White, Jenny (April 27, 2014). Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks – Jenny White. ISBN 9781400851256. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Turkey : Assyrians". Refworld. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- Archived August 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Christen in der islamischen Welt | bpb" (in German). Bpb.de. December 6, 2008. Archived from the original on December 6, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- "Bozdağ: Türkiye'de 349 kilise var" (in Turkish). Milliyet. October 1, 2012. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- "SAT-7 TÜRK". Archived from the original on January 1, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- "Visit to Antakya shows Turkey embraces religious diversity". Mobile.todayszaman.com. November 7, 2010. Archived from the original on January 22, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- "Middle Eastern Christians Flee Violence for Ancient Homeland". News.nationalgeographic.com. December 29, 2014. Archived from the original on August 7, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- "Evangelical in Turkey". SAT-7 UK. April 12, 2015. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- Abazov, Rafis (2009). "2. Thoughts and Religions". Culture and Customs of Turkey. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-34215-8.

- "Istanbul ordination may worsen life for Christians". Church Times. January 18, 2008. Archived from the original on February 14, 2012.

- Hastings, Ed (December 21, 2000). The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought. Oxford University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-19-860024-4. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- "German Site on Christians in Turkey". Kirche-in-not.de. Archived from the original on December 30, 2004.

- Kazhdan, Alexander; Talbot, Alice-Mary (January 1, 2005). "Constantinople, Patriarchate of". The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- Hollingsworth, Paul A.; Cutler, Anthony (January 1, 2005). "Iconoclasm". The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- Curta, Florin; Holt, Andrew (November 28, 2016). Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-566-4.

- Kazhdan, Alexander (January 1, 2005). "Photios". The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- "Divine Office". The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Oxford University Press. January 1, 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-866262-4. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- "Byzantine rite". The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Oxford University Press. January 1, 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-866262-4. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- Kurian, George Thomas; Lamport, Mark A. (May 7, 2015). Encyclopedia of Christian Education. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-8493-9. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- Sluglett, Peter; Weber, Stefan (2010). Syria and Bilad Al-Sham Under Ottoman Rule: Essays in Honour of Abdul Karim Rafeq. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18193-9.

- Winter, Jay (January 8, 2004). America and the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45018-8. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- Chakmakjian, Hagop A. (1965). Armenian Christology and Evangelization of Islam: A Survey of the Relevance of the Christology of the Armenian Apostolic Church to Armenian Relations with Its Muslim Environment. Brill Archive. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 15, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "German Site on Christians in Turkey". Kirche-in-not.de. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- "World Evangelical Alliance". Worldevangelicalalliance.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- "St. Nicholas Center". St. Nicholas Center. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- "St. Georgs-Gemeinde". www.sg.org.tr. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- "Travel to Tao-Klarjeti – Drawings". Tao-klarjeti.ge. Archived from the original on June 2, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- "Artvin"in Gürcü kiliseleri". Radikal (in Turkish). Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- "Barhal Kilisesi". Türkiye Kültür Portalı. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christianity in Turkey. |