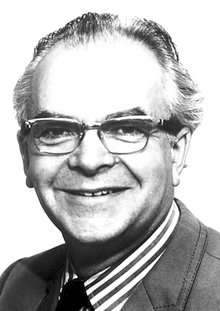

Peter D. Mitchell

Peter Dennis Mitchell, FRS[1] (29 September 1920 – 10 April 1992) was a British biochemist who was awarded the 1978 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his discovery of the chemiosmotic mechanism of ATP synthesis.[2][3]

Peter Mitchell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Peter Dennis Mitchell 29 September 1920[1] |

| Died | 10 April 1992 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | United Kingdom |

| Alma mater | University of Cambridge (BA, MA, PhD) |

| Known for | discovery of the mechanism of ATP synthesis |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biochemistry |

| Institutions | University of Edinburgh |

| Thesis | The rates of synthesis and proportions by weight of the nucleic acid components of a Micrococcus during growth in normal and in penicillin containing media with reference to the bactericidal action of penicillin (1950) |

| Signature | |

Education and early life

Mitchell was born in Mitcham, Surrey on 29 September 1920.[4] His parents were Christopher Gibbs Mitchell, a civil servant, and Kate Beatrice Dorothy (née) Taplin. His uncle was Sir Godfrey Way Mitchell, chairman of George Wimpey.[1] He was educated at Queen's College, Taunton and Jesus College, Cambridge[1] where he studied the Natural Sciences Tripos specialising in Biochemistry.

He was appointed a research post in the Department of Biochemistry, Cambridge, in 1942, and was awarded a Ph.D. in early 1951 for work on the mode of action of penicillin.[5]

Career and research

In 1955 he was invited by Professor Michael Swann to set up a biochemical research unit, called the Chemical Biology Unit, in the Department of Zoology, at the University of Edinburgh, where he was appointed a Senior Lecturer in 1961, then Reader in 1962, although institutional opposition to his work coupled with ill health led to his resignation in 1963.

From 1963 to 1965, he supervised the restoration of a Regency-fronted Mansion, known as Glynn House, at Cardinham near Bodmin, Cornwall - adapting a major part of it for use as a research laboratory. He and his former research colleague, Jennifer Moyle founded a charitable company, known as Glynn Research Ltd., to promote fundamental biological research at Glynn House and they embarked on a programme of research on chemiosmotic reactions and reaction systems.[6][7][8][9] [10]

Chemiosmotic hypothesis

In the 1960s, ATP was known to be the energy currency of life, but the mechanism by which ATP was created in the mitochondria was assumed to be by substrate-level phosphorylation. Mitchell's chemiosmotic hypothesis was the basis for understanding the actual process of oxidative phosphorylation. At the time, the biochemical mechanism of ATP synthesis by oxidative phosphorylation was unknown.

Mitchell realised that the movement of ions across an electrochemical potential difference could provide the energy needed to produce ATP. His hypothesis was derived from information that was well known in the 1960s. He knew that living cells had a membrane potential; interior negative to the environment. The movement of charged ions across a membrane is thus affected by the electrical forces (the attraction of positive to negative charges). Their movement is also affected by thermodynamic forces, the tendency of substances to diffuse from regions of higher concentration. He went on to show that ATP synthesis was coupled to this electrochemical gradient.[11]

His hypothesis was confirmed by the discovery of ATP synthase, a membrane-bound protein that uses the potential energy of the electrochemical gradient to make ATP; and by the discovery by André Jagendorf that a pH difference across the thylakoid membrane in the chloroplast results in ATP synthesis.[12]

Protonmotive Q-cycle

Later, Peter Mitchell also hypothesized some of the complex details of electron transport chains. He conceived of the coupling of proton pumping to quinone-based electron bifurcation, which contributes to the proton motive force and thus, ATP synthesis.[13]

Awards and honours

In 1978 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry "for his contribution to the understanding of biological energy transfer through the formulation of the chemiosmotic theory."[14] He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1974.[1][15]

References

- Slater, E. C. (1994). "Peter Dennis Mitchell. 29 September 1920 – 10 April 1992". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 40: 282–305. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1994.0040.

- "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/51236. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Peter D. Mitchell biography

- NNDB. "Peter Mitchell Bio at NNDB". Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- Mitchell, Peter Dennis (1950). The rates of synthesis and proportions by weight of the nucleic acid components of a Micrococcus during growth in normal and in penicillin containing media with reference to the bactericidal action of penicillin (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge.

- Mitchell, P. (1966). "Chemiosmotic Coupling in Oxidative and Photosynthetic Phosphorylation". Biological Reviews. 41 (3): 445–502. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1966.tb01501.x. PMID 5329743.

- Mitchell, P. (1972). "Chemiosmotic coupling in energy transduction: A logical development of biochemical knowledge". Journal of Bioenergetics. 3 (1): 5–24. doi:10.1007/BF01515993. PMID 4263930.

- Greville, G.D. (1969). "A scrutiny of Mitchell's chemiosmotic hypothesis of respiratory chain and photosynthetic phosphorylation". Curr. Topics Bioenergetics. Current Topics in Bioenergetics. 3: 1–78. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4831-9971-9.50008-0. ISBN 9781483199719.

- Mitchell, P. (1970). "Aspects of the chemiosmotic hypothesis". The Biochemical Journal. 116 (4): 5P–6P. doi:10.1042/bj1160005p. PMC 1185429. PMID 4244889.

- Mitchell, P. (1976). "Possible molecular mechanisms of the protonmotive function of cytochrome systems". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 62 (2): 327–367. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(76)90124-7. PMID 186667.

- Mitchell, P. (1961). "Coupling of Phosphorylation to Electron and Hydrogen Transfer by a Chemi-Osmotic type of Mechanism" (PDF). Nature. 191 (4784): 144–148. Bibcode:1961Natur.191..144M. doi:10.1038/191144a0. PMID 13771349.

- Jagendorf A. T. and E. Uribe (1966). "ATP formation caused by acid-base transition of spinach chloroplasts". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 55 (1): 170–177. Bibcode:1966PNAS...55..170J. doi:10.1073/pnas.55.1.170. PMC 285771. PMID 5220864.

- Mitchell, Peter (15 November 1975). "The protonmotive Q cycle: A general formulation". FEBS Letters. 59 (2): 137–139. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(75)80359-0. ISSN 1873-3468. PMID 1227927.

- "Mitchell's 1978 Nobel speech". Retrieved 23 March 2007.

- "Fellowship of the Royal Society 1660-2015". London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015.