Mainz

Mainz (/maɪnts/; German: [maɪ̯nt͡s] (![]()

Mainz | |

|---|---|

Mainz Old Town view from the citadel (November 2003) | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

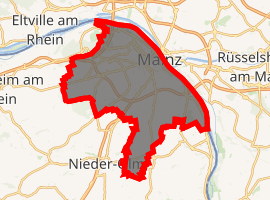

Location of Mainz

| |

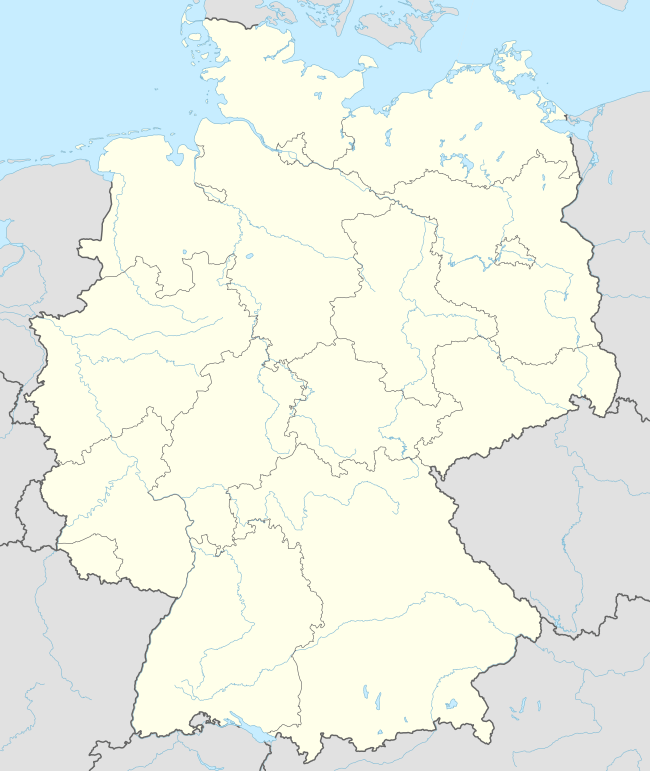

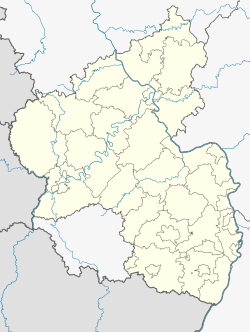

Mainz  Mainz | |

| Coordinates: 50°0′N 8°16′E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Rhineland-Palatinate |

| District | Urban district |

| Founded | 13/12 BC |

| Subdivisions | 15 boroughs |

| Government | |

| • Lord Mayor | Michael Ebling (SPD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 97.75 km2 (37.74 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 285 m (935 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 85 m (279 ft) |

| Population (2018-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 217,118 |

| • Density | 2,200/km2 (5,800/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 55116–55131 |

| Dialling codes | 06131, 06136 |

| Vehicle registration | MZ |

| Website | www.mainz.de |

Mainz was founded by the Romans in the 1st century BC during the Classical antiquity era, serving as a military fortress on the northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire and as the provincial capital of Germania Superior. Mainz became an important city in the 8th century AD as part of the Holy Roman Empire, becoming the capital of the Electorate of Mainz and seat of the Archbishop-Elector of Mainz, the Primate of Germany. Mainz is famous as the home of Johannes Gutenberg, the inventor of the movable-type printing press, who in the early 1450s manufactured his first books in the city, including the Gutenberg Bible. Mainz was heavily damaged during World War II, with more than 30 air raids destroying about 80 percent of the city's center, including most of the historic buildings. Today, Mainz is a transport hub and a center of wine production.

Geography

Topography

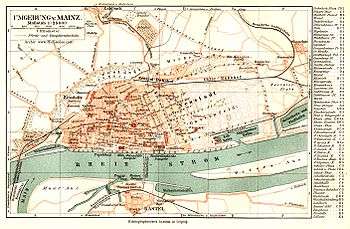

Mainz is located on the 50th latitude, on the left bank of the river Rhine, opposite the confluence of the Main with the Rhine. The population in the early 2012 was 200,957, an additional 18,619 people maintain a primary residence elsewhere but have a second home in Mainz. The city is part of the Rhein Metro area comprising 5.8 million people. Mainz can easily be reached from Frankfurt International Airport in 25 minutes by commuter railway (Line S8).

Mainz is a river port city as the Rhine which connects with its main tributaries, such as the Neckar, the Main and, later, the Moselle and thereby continental Europe with the Port of Rotterdam and thus the North Sea. Mainz's history and economy are closely tied to its proximity to the Rhine historically handling much of the region's waterborne cargo. Today's huge container port hub allowing trimodal transport is located on the North Side of the town. The river also provides another positive effect, moderating Mainz's climate; making waterfront neighborhoods slightly warmer in winter and cooler in summer.

After the last ice age, sand dunes were deposited in the Rhine valley at what was to become the western edge of the city. The Mainz Sand Dunes area is now a nature reserve with a unique landscape and rare steppe vegetation for this area.

While the Mainz legion camp was founded in 13/12 BC on the Kästrich hill, the associated vici and canabae (civilian settlements) were erected in the direction of the Rhine. Historical sources and archaeological findings both prove the importance of the military and civilian Mogontiacum as a port city on the Rhine.[3]

Climate

Mainz experiences an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb).

| Climate data for Mainz | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

5.3 (41.5) |

9.7 (49.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

19 (66) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24 (75) |

23.6 (74.5) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.3 (57.7) |

8 (46) |

4.5 (40.1) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.2 (29.8) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

1.9 (35.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

13.2 (55.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

5.9 (42.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 38 (1.5) |

36 (1.4) |

38 (1.5) |

38 (1.5) |

51 (2) |

58 (2.3) |

56 (2.2) |

53 (2.1) |

41 (1.6) |

43 (1.7) |

48 (1.9) |

46 (1.8) |

550 (21.5) |

| Source: Intellicast[4] | |||||||||||||

History

Roman Mogontiacum

The Roman stronghold or castrum Mogontiacum, the precursor to Mainz, was founded by the Roman general Drusus perhaps as early as 13/12 BC. As related by Suetonius the existence of Mogontiacum is well established by four years later (the account of the death and funeral of Nero Claudius Drusus), though several other theories suggest the site may have been established earlier.[5] Although the city is situated opposite the mouth of the Main, the name of Mainz is not from Main, the similarity being perhaps due to diachronic analogy. Main is from Latin Menus, the name the Romans used for the river. Linguistic analysis of the many forms that the name "Mainz" has taken on make it clear that it is a simplification of Mogontiacum.[6] The name appears to be Celtic and ultimately it is. However, it had also become Roman and was selected by them with a special significance. The Roman soldiers defending Gallia had adopted the Gallic god Mogons (Mogounus, Moguns, Mogonino), for the meaning of which etymology offers two basic options: "the great one", similar to Latin magnus, which was used in aggrandizing names such as Alexander magnus, "Alexander the Great" and Pompeius magnus, "Pompey the great", or the god of "might" personified as it appears in young servitors of any type whether of noble or ignoble birth.[7]

Mogontiacum was an important military town throughout Roman times, probably due to its strategic position at the confluence of the Main and the Rhine. The town of Mogontiacum grew up between the fort and the river. The castrum was the base of Legio XIV Gemina and XVI Gallica (AD 9–43), XXII Primigenia, IV Macedonica (43–70), I Adiutrix (70–88), XXI Rapax (70–89), and XIV Gemina (70–92), among others. Mainz was also a base of a Roman river fleet, the Classis Germanica. Remains of Roman troop ships (navis lusoria) and a patrol boat from the late 4th century were discovered in 1982/86 and may now be viewed in the Museum für Antike Schifffahrt. A temple dedicated to Isis Panthea and Magna Mater was discovered in 2000[8] and is open to the public.[9] The city was the provincial capital of Germania Superior, and had an important funeral monument dedicated to Drusus, to which people made pilgrimages for an annual festival from as far away as Lyon. Among the famous buildings were the largest theatre north of the Alps and a bridge across the Rhine. The city was also the site of the assassination of emperor Severus Alexander in 235.

Alemanni forces under Rando sacked the city in 368. From the last day of 405[10] or 406, the Siling and Asding Vandals, the Suebi, the Alans, and other Germanic tribes crossed the Rhine, possibly at Mainz. Christian chronicles relate that the bishop, Aureus, was put to death by the Alemannian Crocus. The way was open to the sack of Trier and the invasion of Gaul.

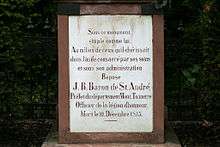

Throughout the changes of time, the Roman castrum never seems to have been permanently abandoned as a military installation, which is a testimony to Roman military judgement. Different structures were built there at different times. The current citadel originated in 1660, but it replaced previous forts. It was used in World War II. One of the sights at the citadel is still the cenotaph raised by legionaries to commemorate their Drusus.

Frankish Mainz

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 50 | 16,000 | — |

| 750 | 5,000 | −68.8% |

| 1300 | 24,000 | +380.0% |

| 1545 | 10,000 | −58.3% |

| 1700 | 20,000 | +100.0% |

| 1816 | 25,251 | +26.3% |

| 1871 | 53,902 | +113.5% |

| 1900 | 84,251 | +56.3% |

| 1910 | 110,634 | +31.3% |

| 1925 | 108,552 | −1.9% |

| 1933 | 142,627 | +31.4% |

| 1939 | 158,533 | +11.2% |

| 1950 | 88,369 | −44.3% |

| 1961 | 134,375 | +52.1% |

| 1970 | 172,195 | +28.1% |

| 1987 | 172,529 | +0.2% |

| 2011 | 200,344 | +16.1% |

| 2018 | 217,118 | +8.4% |

| source:[11] | ||

Through a series of incursions during the 4th century Alsace gradually lost its Belgic ethnic character of formerly Germanic tribes among Celts ruled by Romans and became predominantly influenced by the Alamanni. The Romans repeatedly re-asserted control; however, the troops stationed at Mainz became chiefly non-Italic and the emperors had only one or two Italian ancestors in a pedigree that included chiefly peoples of the northern frontier.

The last emperor to station troops serving the western empire at Mainz was Valentinian III (reigned 425–455), who relied heavily on his Magister militum per Gallias, Flavius Aëtius. By that time the army included large numbers of troops from the major Germanic confederacies along the Rhine, the Alamanni, the Saxons and the Franks. The Franks were an opponent that had risen to power and reputation among the Belgae of the lower Rhine during the 3rd century and repeatedly attempted to extend their influence upstream. In 358 the emperor Julian bought peace by giving them most of Germania Inferior, which they possessed anyway, and imposing service in the Roman army in exchange.

European factions in the time of master Aëtius included Celts, Goths, Franks, Saxons, Alamanni, Huns, Italians, and Alans as well as numerous other minor peoples. Aëtius played them all off against one another in a masterly effort to keep the peace under Roman sovereignty. He used Hunnic troops a number of times. At last a day of reckoning arrived between Aëtius and Attila, both commanding polyglot, multi-ethnic troops. Attila went through Alsace in 451, devastating the country and destroying Mainz and Trier with their Roman garrisons. Shortly after he was thwarted by Flavius Aëtius at the Battle of Châlons, the largest of the ancient world.

Aëtius was not to enjoy the victory long. He was assassinated in 454 by the hand of his employer, who in turn was stabbed to death by friends of Aëtius in 455. As far as the north was concerned this was the effective end of the Roman empire there. After some sanguinary but relatively brief contention a former subordinate of Aëtius, Ricimer, became commander in chief, and was named Patrician. His father was a Suebian; his mother, a princess of the Visigoths. Ricimer did not rule the north directly but set up a client province there, which functioned independently. The capital was at Soissons. Even then its status was equivocal. Many insisted it was the Kingdom of Soissons. which extended across northern France and was ruled in the name of Rome by Aegidius, an ally of emperor Majorian, 457–461, who died about 464. He was succeeded by his son, Syagrius, who was defeated by Clovis in 486.

Previously the first of the Merovingians, Clodio, had been defeated by Aëtius at about 430. His son, Merovaeus, fought on the Roman side against Attila, and his son, Childeric, served in the domain of Soissons. Meanwhile, the Franks were gradually infiltrating and assuming power in this domain from Txxandria (northern Belgium which had been given to them by the Romans to protect as allies). They also moved up the Rhine and created a domain in the region of the former Germania Superior with capital at Cologne. They became known as the Ripuarian Franks as opposed to the Salian Franks. Events moved rapidly in the late 5th century.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, the Franks under the rule of Clovis I gained control over western Europe by the year 496. Clovis, son of Childeric, became king of the Salians in 481, ruling from Tournai. In 486 he defeated Syagrius, last governor of the Soissons domain, and took northern France. He extended his reign to Cambrai and Tongeren in 490–491, and repelled the Alamanni in 496. Also in that year he converted to Catholicism from non-Arian Christianity. Clovis annexed the kingdom of Cologne in 508. Thereafter, Mainz, in its strategic position, became one of the bases of the Frankish kingdom. Mainz had sheltered a Christian community long before the conversion of Clovis. His successor Dagobert I reinforced the walls of Mainz and made it one of his seats. A solidus of Theodebert I (534–548) was minted at Mainz.

Charlemagne (768–814), through a succession of wars against other tribes, built a vast Frankian empire in Europe. Mainz from its central location became important to the empire and to Christianity. Meanwhile, language change was gradually working to divide the Franks. Mainz spoke a dialect termed Ripuarian. On the death of Charlemagne, distinctions between France and Germany began to be made. Mainz was not central any longer but was on the border, creating a question of the nationality to which it belonged, which descended into modern times as the question of Alsace-Lorraine.

Christian Mainz

Free City of Mainz Freie Stadt Mainz | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1244–1462 | |||||||||

| Status | Imperial city | ||||||||

| Capital | Mainz | ||||||||

| Government | Imperial city | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• City established | c. 13 BC | ||||||||

| 1244 | |||||||||

• Rival archbishops | 1461 | ||||||||

| 1462 | |||||||||

• German Mediatisation | 1803 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

In the early Middle Ages, Mainz was a centre for the Christianisation of the German and Slavic peoples. The first archbishop in Mainz, Boniface, was killed in 754 while trying to convert the Frisians to Christianity and is buried in Fulda. Boniface held a personal title of archbishop; Mainz became a regular archbishopric see in 781, when Boniface's successor Lullus was granted the pallium by Pope Adrian I. Harald Klak, king of Jutland, his family and followers, were baptized at Mainz in 826, in the abbey of St. Alban's.[12] Other early archbishops of Mainz include Rabanus Maurus, the scholar and author, and Willigis (975–1011), who began construction on the current building of the Mainz Cathedral and founded the monastery of St. Stephan.

From the time of Willigis until the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the Archbishops of Mainz were archchancellors of the Empire and the most important of the seven Electors of the German emperor. Besides Rome, the diocese of Mainz today is the only diocese in the world with an episcopal see that is called a Holy See (sancta sedes). The Archbishops of Mainz traditionally were primas germaniae, the substitutes of the Pope north of the Alps.

In 1244, Archbishop Siegfried III granted Mainz a city charter, which included the right of the citizens to establish and elect a city council. The city saw a feud between two archbishops in 1461, namely Diether von Isenburg, who was elected Archbishop by the cathedral chapter and supported by the citizens, and Adolf II von Nassau, who had been named archbishop for Mainz by the pope. In 1462, the Archbishop Adolf raided the city of Mainz, plundering and killing 400 inhabitants. At a tribunal, those who had survived lost all their property, which was then divided between those who promised to follow Adolf. Those who would not promise to follow Adolf (amongst them Johannes Gutenberg) were driven out of the town or thrown into prison. The new archbishop revoked the city charter of Mainz and put the city under his direct rule. Ironically, after the death of Adolf II his successor was again Diether von Isenburg, now legally elected by the chapter and named by the Pope.

Early Jewish community

The Jewish community of Mainz dates to the 10th century CE. It is noted for its religious education. Rabbi Gershom ben Judah (960–1040) taught there, among others. He concentrated on the study of the Talmud, creating a German Jewish tradition. Mainz is also the legendary home of the martyred Rabbi Amnon of Mainz, composer of the Unetanneh Tokef prayer. The Jews of Mainz, Speyer and Worms created a supreme council to set standards in Jewish law and education in the 12th century.

The city of Mainz responded to the Jewish population in a variety of ways, behaving, in a sense, in a bipolar fashion towards them. Sometimes they were allowed freedom and were protected; at other times, they were persecuted. The Jews were expelled in 1012, 1462 (after which they were invited to return), and in 1474. Jews were attacked in 1096 and by mobs in 1283. Outbreaks of the Black Death were usually blamed on the Jews, at which times they were massacred, such as the burning of 11 Jews alive in 1349.[13]

Nowadays the Jewish community is growing rapidly, and a new synagogue by the architect Manuel Herz was constructed in 2010 on the site of the one destroyed by the Nazis on Kristallnacht in 1938.[14] The community itself has 1,034 members, according to the Central Council of Jews in Germany, and at least twice as many Jews altogether since many are unaffiliated with Judaism.

Republic of Mainz

During the French Revolution, the French Revolutionary army occupied Mainz in 1792; the Archbishop of Mainz, Friedrich Karl Josef von Erthal, had already fled to Aschaffenburg by the time the French marched in. On 18 March 1793, the Jacobins of Mainz, with other German democrats from about 130 towns in the Rhenish Palatinate, proclaimed the 'Republic of Mainz'. Led by Georg Forster, representatives of the Mainz Republic in Paris requested political affiliation of the Mainz Republic with France, but too late: Prussia was not entirely happy with the idea of a democratic free state on German soil (although the French dominated Mainz was neither free nor democratic). Prussian troops had already occupied the area and besieged Mainz by the end of March 1793. After a siege of 18 weeks, the French troops in Mainz surrendered on 23 July 1793; Prussians occupied the city and ended the Republic of Mainz. It came to the Battle of Mainz in 1795 between Austria and France. Members of the Mainz Jacobin Club were mistreated or imprisoned and punished for treason.

In 1797, the French returned. The army of Napoléon Bonaparte occupied the German territory to the west of the Rhine, and the Treaty of Campo Formio awarded France this entire area. On 17 February 1800, the French Département du Mont-Tonnerre was founded here, with Mainz as its capital, the Rhine being the new eastern frontier of la Grande Nation. Austria and Prussia could not but approve this new border with France in 1801. However, after several defeats in Europe during the next years, the weakened Napoléon and his troops had to leave Mainz in May 1814.[15]

Rhenish Hesse

In 1816, the part of the former French Département which is known today as Rhenish Hesse (German: Rheinhessen) was awarded to the Hesse-Darmstadt, Mainz being the capital of the new Hessian province of Rhenish Hesse. From 1816 to 1866, to the German Confederation Mainz was the most important fortress in the defence against France, and had a strong garrison of Austrian, Prussian and Bavarian troops.

In the afternoon of 18 November 1857, a huge explosion rocked Mainz when the city's powder magazine, the Pulverturm, exploded. Approximately 150 people were killed and at least 500 injured; 57 buildings were destroyed and a similar number severely damaged in what was to be known as the Powder Tower Explosion or Powder Explosion.

During the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, Mainz was declared a neutral zone. After the founding of the German Empire in 1871, Mainz no longer was as important a stronghold, because in the war of 1870/71 France had lost the territory of Alsace-Lorraine to Germany (which France had occupied piece by piece 1630/1795), and this defined the new border between the two countries.

Industrial expansion

For centuries the inhabitants of the fortress of Mainz had suffered from a severe shortage of space which led to disease and other inconveniences. In 1872 Mayor Carl Wallau and the council of Mainz persuaded the military government to sign a contract to expand the city. Beginning in 1874, the city of Mainz assimilated the Gartenfeld, an idyllic area of meadows and fields along the banks of the Rhine to the north of the rampart. The city expansion more than doubled the urban area which allowed Mainz to participate in the industrial revolution which had previously avoided the city for decades.

Eduard Kreyßig was the man who made this happen. Having been the master builder of the city of Mainz since 1865, Kreyßig had the vision for the new part of town, the Neustadt. He also planned the first sewer system for the old part of town since Roman times and persuaded the city government to relocate the railway line from the Rhine side to the west end of the town. The main station was built from 1882 to 1884 according to the plans of Philipp Johann Berdellé.

The Mainz master builder constructed a number of state-of-the-art public buildings, including the Mainz town hall — which was the largest of its kind in Germany at that time — as well a synagogue, the Rhine harbour and a number of public baths and school buildings. Kreyßig's last work was Christ Church (Christuskirche), the largest Protestant church in the city and the first building constructed solely for the use of a Protestant congregation. In 1905 the demolition of the entire circumvallation and the Rheingauwall was taken in hand, according to imperial order of Wilhelm II.

20th century

During the German Revolution of 1918 the Mainz Workers' and Soldiers' Council was formed which ran the city from 9 November until the arrival of French troops under the terms of the occupation of the Rhineland agreed in the Armistice. The French occupation was confirmed by the Treaty of Versailles which went into effect 28 June 1919. The Rhineland (in which Mainz is located) was to be a demilitarized zone until 1935 and the French garrison, representing the Triple Entente, was to stay until reparations were paid.

In 1923 Mainz participated in the Rhineland separatist movement that proclaimed a republic in the Rhineland. It collapsed in 1924. The French withdrew on 30 June 1930. Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany in January 1933 and his political opponents, especially those of the Social Democratic Party, were either incarcerated or murdered. Some were able to move away from Mainz in time. One was the political organizer for the SPD, Friedrich Kellner, who went to Laubach, where as the chief justice inspector of the district court he continued his opposition against the Nazis by recording their misdeeds in a 900-page diary.

In March 1933, a detachment from the National Socialist Party in Worms brought the party to Mainz. They hoisted the swastika on all public buildings and began to denounce the Jewish population in the newspapers. In 1936, the Nazis remilitarized the Rhineland with great fanfare, the first move of Nazi Germany's meteoric expansion. The former Triple Entente took no action.

During World War II the citadel at Mainz hosted the Oflag XII-B prisoner of war camp.

The Bishop of Mainz, Albert Stohr, formed an organization to help Jews escape from Germany.

During World War II, more than 30 air raids destroyed about 80 percent of the city's center, including most of the historic buildings. Mainz was captured on 22 March 1945 against uneven German resistance (staunch in some sectors and weak in other parts of the city) by the 90th Infantry Division under William A. McNulty, a formation of the XII Corps under Third Army commanded by General George S. Patton, Jr.[16] Patton used the ancient strategic gateway through Germania Superior to cross the Rhine south of Mainz, drive down the Danube towards Czechoslovakia and end the possibility of a Bavarian redoubt crossing the Alps in Austria when the war ended.

From 1945 to 1949, the city was part of the French zone of occupation. When the federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate was founded on 30 August 1946 by the commander of the French army on the French occupation zone Marie Pierre Kœnig, Mainz became capital of the new state.[17] In 1962, the diarist, Friedrich Kellner, returned to spend his last years in Mainz. His life in Mainz, and the impact of his writings, is the subject of the Canadian documentary My Opposition: The Diaries of Friedrich Kellner.

Following the withdrawal of French forces from Mainz, the United States Army Europe occupied the military bases in Mainz. Today USAREUR only occupies McCulley Barracks in Wackernheim and the Mainz Sand Dunes for training area. Mainz is home to the headquarters of the Bundeswehr's Landeskommando Rhineland-Palatinate and other units.

Cityscape

Architecture

The destruction caused by the bombing of Mainz during World War II led to the most intense phase of building in the history of the town. During the last war in Germany, more than 30 air raids destroyed about 80 percent of the city's center, including most of the historic buildings.[18] The destructive attack on the afternoon of 27 February 1945 remains the most destructive of all 33 bombings that Mainz has suffered in World War II in the collective memory of most of the population living then. The air raid caused most of the dead and made an already hard-hit city largely leveled.[19][20][21]

Nevertheless, the post-war reconstruction took place very slowly. While cities such as Frankfurt had been rebuilt fast by a central authority, only individual efforts were initially successful in rebuilding Mainz. The reason for this was that the French wanted Mainz to expand and to become a model city. Mainz lay within the French-controlled sector of Germany and it was a French architect and town-planner, Marcel Lods, who produced a Le Corbusier-style plan of an ideal architecture.[22][23][24] But the very first interest of the inhabitants was the restoration of housing areas. Even after the failure of the model city plans it was the initiative of the French (founding of the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz, elevation of Mainz to the state capital of Rhineland-Palatinate, the early resumption of the Mainz carnival) driving the city in a positive development after the war. The City Plan of 1958 by Ernst May allowed a regulated reconstruction for the first time. In 1950, the seat of the government of Rhineland-Palatinate had been transferred to the new Mainz and in 1963 the seat of the new ZDF, notable architects were Adolf Bayer, Richard Jörg and Egon Hartmann. At the time of the two-thousand-years-anniversary in 1962 the city was largely reconstructed. During the 1950s and 1960s the Oberstadt had been extended, Münchfeld and Lerchenberg added as suburbs, the Altstadttangente (intersection of the old town), new neighbourhoods as Westring and Südring contributed to the extension. By 1970 there remained only a few ruins. The new town hall of Mainz had been designed by Arne Jacobsen and finished by Dissing+Weitling. The town used Jacobsens activity for the Danish Novo erecting a new office and warehouse building to contact him. The urban renewal of the old town changed the inner city. In the framework of the preparation of the cathedrals millennium, pedestrian zones were developed around the cathedral, in northern direction to the Neubrunnenplatz and in southern direction across the Leichhof to the Augustinerstraße and Kirschgarten. The 1980s brought the renewal of the façades on the Markt and a new inner-city neighbourhood on the Kästrich. During the 1990s the Kisselberg between Gonsenheim and Bretzenheim, the "Fort Malakoff Center" at the site of the old police barracks, the renewal of the Main Station and the demolition of the first post-war shopping center at the Markt followed by the erection of a new historicising building at the same place.

Main sights

- Romano-Germanic Central Museum (Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum). It is home to Roman, Medieval, and earlier artifacts.

- Museum of Ancient Seafaring (Museum für Antike Schifffahrt). It houses the remains of five Roman boats from the late 4th century, discovered in the 1980s.

- Roman remains, including Jupiter's column, Drusus' mausoleum, the ruins of the theatre and the aqueduct.

- Mainz Cathedral of St. Martin (Mainzer Dom), over 1,000 years old.

- St. John's Church, 7th-century church building

- Staatstheater Mainz

- The Iron Tower (Eisenturm, tower at the former iron market), a 13th-century gate-tower.

- The Wood Tower (Holzturm, tower at the former wood market), a 15th-century gate tower.

- The Gutenberg Museum – exhibits an original Gutenberg Bible amongst many other printed books from the 15th century and later.

- The Mainz Old Town – what's left of it, the quarter south of the cathedral survived World War II.

- The old arsenal, the central arsenal of the fortress Mainz during the 17th and 18th century

- The Electoral Palace (Kurfürstliches Schloss), residence of the prince-elector.

- The Marktbrunnen, one of the largest Renaissance fountains in Germany.

- Domus Universitatis (1615), for centuries the tallest edifice in Mainz.

- Christ Church (Christuskirche), built 1898–1903, bombed in 1945 and rebuilt in 1948–1954.

- The Church of St. Stephan, with post-war windows by Marc Chagall.

- Citadel.

- The ruins of the church St. Christoph, a World War II memorial

- Schönborner Hof (1668).

- Rococo churches of St. Augustin (the Augustinerkirche, Mainz) and St. Peter (the Peterskirche, Mainz).

- Churches of St. Ignatius (1763) and St. Quintin.

- Erthaler Hof (1743)

- The Baroque Bassenheimer Hof (1750)

- The Botanischer Garten der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, a botanical garden maintained by the university

- Landesmuseum Mainz, state museum with archaeology and art.

- Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (ZDF) – one of the largest public German TV-Broadcaster.

- New synagogue in Mainz

- Kunsthalle Mainz – museum for contemporary art

Administration

The city of Mainz is divided into 15 local districts according to the main statute of the city of Mainz. Each local district has a district administration of 13 members and a directly elected mayor, who is the chairman of the district administration. This local council decides on important issues affecting the local area, however, the final decision on new policies is made by the Mainz's municipal council.

In accordance with section 29 paragraph 2 Local Government Act of Rhineland-Palatinate, which refers to municipalities of more than 150,000 inhabitants, the city council has 60 members.

Districts of the town are:

|

|

|

Until 1945, the districts of Bischofsheim (now an independent town), Ginsheim-Gustavsburg (which together are an independent town) belonged to Mainz. The former districts Amöneburg, Kastel, and Kostheim — (in short, AKK) are now administrated by the city of Wiesbaden (on the north bank of the river). The AKK was separated from Mainz when the Rhine was designated the boundary between the French occupation zone (the later state of Rhineland-Palatinate) and the U.S. occupation zone (Hesse) in 1945.

Coat of arms

The coat of arms of Mainz is derived from the coat of arms of the Archbishops of Mainz and features two six-spoked silver wheels connected by a silver cross on a red background.

Culture

Mainz is home to a Carnival, the Mainzer Fassenacht or Fastnacht, which has developed since the early 19th century. Carnival in Mainz has its roots in the criticism of social and political injustices under the shelter of cap and bells. Today, the uniforms of many traditional Carnival clubs still imitate and caricature the uniforms of the French and Prussian troops of the past. The height of the carnival season is on Rosenmontag ("rose Monday"), when there is a large parade in Mainz, with more than 500,000 people celebrating in the streets.

The first ever Katholikentag, a festival-like gathering of German Catholics, was held in Mainz in 1848.

Johannes Gutenberg, credited with the invention of the modern printing press with movable type, was born here and died here. Since 1968 the Mainzer Johannisnacht commemorates the person Johannes Gutenberg in his native city. The Mainz University, which was refounded in 1946, is named after Gutenberg; the earlier University of Mainz that dated back to 1477 had been closed down by Napoleon's troops in 1798.

Mainz was one of three important centers of Jewish theology and learning in Central Europe during the Middle Ages. Known collectively as Shum, the cities of Speyer, Worms and Mainz played a key role in the preservation and propagation of Talmudic scholarship.

The city is the seat of Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (literally, "Second German Television", ZDF), one of two federal nationwide TV broadcasters. There are also a couple of radio stations based in Mainz.

Other cultural aspects of the city include:

- As city in the Greater Region, Mainz participated in the program of the year of European Capital of Culture 2007.

- The Walk of Fame of Cabaret may be found nearby the Schillerplatz.

- The music publisher Schott Music is located in Mainz.

- One of the oldest brass instrument manufacturers in the world, Gebr. Alexander is located in Mainz.

- Fans of Gospel music enjoy the yearly performances of Colours of Gospel.

Education

- University of Mainz

- University of Applied Sciences Mainz

- Catholic University of Applied Sciences Mainz

Sports

The local football club 1. FSV Mainz 05 has a long history in the German football leagues. Since 2004 it has competed in the Bundesliga (First German soccer league) except a break in second level in 2007–08 season. Mainz is closely associated with renowned coach Jürgen Klopp, who spent the vast majority of his playing career at the club and was also the manager for seven years, leading the club to Bundesliga football for the first time. After leaving Mainz Klopp went on to win two Bundesliga titles and reaching a Champions League final with Borussia Dortmund. In the summer 2011 the club opened its new stadium called Coface Arena, which was later renamed to Opel Arena. Further relevant football clubs are TSV Schott Mainz, SV Gonsenheim, Fontana Finthen, FC Fortuna Mombach and FVgg Mombach 03.

The local wrestling club ASV Mainz 1888 is currently in the top division of team wrestling in Germany, the Bundesliga. In 1973, 1977 and 2012 the ASV Mainz 1888 won the German championship.

In 2007 the Mainz Athletics won the German Men's Championship in baseball.

As a result of the 2008 invasion of Georgia by Russian troops, Mainz acted as a neutral venue for the Georgian Vs Republic of Ireland football game.

The biggest basketball club in the city is the ASC Theresianum Mainz. Its men's team is playing in the Regionalliga and its women's team is playing in the 2.DBBL.[25]

USC Mainz

Universitäts-Sportclub Mainz (University Sports Club Mainz) is a German sports club based in Mainz. It was founded on 9 September 1959[26] by Berno Wischmann primarily for students of the University of Mainz. It is considered one of the most powerful Athletics Sports clubs in Germany. 50 athletes of USC have distinguished themselves in a half-century in club history at Olympic Games, World and European Championships. In particular in the decathlon dominated USC athletes for decades: Already at the European Championships in Budapest in 1966 Mainz won three (Werner von Moltke, Jörg Mattheis and Horst Beyer) all decathlon medals. In the all-time list of the USC, there are nine athletes who have achieved more than 8,000 points – at the head of Siegfried Wentz (8762 points in 1983) and Guido Kratschmer (1980 world record with 8667 points). Most successful athlete of the association is more fighter, sprinter and long jumper Ingrid Becker (Olympic champion in 1968 in the pentathlon and Olympic champion in 1972 in the 4 × 100 Metres Relay and European champion in 1971 in the long jump). Most famous athletes of the present are the sprinter Marion Wagner (world champion in 2001 in the 4 × 100 Metres Relay) and the pole vaulters Carolin Hingst (Eighth of the 2008 Olympics in Beijing) and Anna Battke.

Three world titles adorn the balance of USC Mainz. For the discus thrower Lars Riedel attended (1991 and 1993) and the already mentioned sprinter Marion Wagner (2001). Added to 5 titles at the European Championships, a total of 65 international medals and 260 victories at the German Athletics Championships.[27]

The players of USC's basketball section played from the season 1968/69 to the season 1974/75 in the National Basketball League (BBL) of the German Basketball Federation (DBB). As a finalist to winning the DBB Cup in 1971 USC Mainz played in the 1971–72 FIBA European Cup Winners' Cup against the Italian Cup winners of Fides Napoli.[28]

Mainz Athletics

The Baseball and Softball Club Mainz Athletics is a German baseball and softball club located in the city of Mainz in Rhineland-Palatinate. The Athletics is one of the largest clubs in the Baseball-Bundesliga Süd in terms of membership, claiming to have hundreds of active players. The club has played in the Baseball-Bundesliga for more than two decades, and has won the German Championship in 2007 and 2016.

Economy

Wine centre

Mainz is one of the centers of the German wine economy[29] as a center for wine trade and the seat of the state's wine minister. Due to the importance and history of the wine industry for the federal state, Rhineland-Palatinate is the only state to have such a department.

Since 2008, the city is also member of the Great Wine Capitals Global Network (GWC), an association of well-known wineculture-cities of the world.[30] Many wine traders also work in the town. The sparkling wine producer Kupferberg produced in Mainz-Hechtsheim and even Henkell — now located on the other side of the river Rhine — had been founded once in Mainz. The famous Blue Nun, one of the first branded wines, had been marketed by the family Sichel.

Mainz had been a wine growing region since Roman times and the image of the wine town Mainz is fostered by the tourist center. The Haus des Deutschen Weines (English: House of German Wine), is located in beside the theater. The Mainzer Weinmarkt (wine market) is one of the great wine fairs in Germany.

Other industries

The Schott AG, one of the world's largest glass manufactures, as well as the Werner & Mertz, a large chemical factory, are based in Mainz. Other companies such as IBM, QUINN Plastics, or Novo Nordisk have their German administration in Mainz as well.

Johann-Joseph Krug, founder of France's famous Krug champagne house in 1843, was born in Mainz in 1800.

Transport

Mainz is a major transport hub in southern Germany. It is an important component in European distribution, as it has the fifth largest inter-modal port in Germany. The Port of Mainz, now handling mainly containers, is a sizable industrial area to the north of the city, along the banks of the Rhine. In order to open up space along the city's riverfront for residential development, it was shifted further northwards in 2010.

Rail

Mainz Central Station or Mainz Hauptbahnhof, is frequented by 80,000 travelers and visitors each day and is therefore one of the busiest 21 stations in Germany. It is a stop for the S-Bahn line S8 of the Rhein-Main-Verkehrsverbund. Additionally, the Mainbahn line to Frankfurt Hbf starts at the station. It is served by 440 daily local and regional trains (StadtExpress, RE and RB) and 78 long-distance trains (IC, EC and ICE). Intercity-Express lines connect Mainz with Frankfurt (Main), Karlsruhe Hbf, Worms Hauptbahnhof and Koblenz Hauptbahnhof. It is a terminus of the West Rhine Railway and the Mainz–Ludwigshafen railway, as well as the Alzey–Mainz Railway erected by the Hessische Ludwigsbahn in 1871. Access to the East Rhine Railway is provided by the Kaiserbrücke, a railway bridge across the Rhine at the north end of Mainz.

Operational usage

| In brief | |

|---|---|

| Number of passenger tracks above ground: |

7 main line, 1 branch, 1 tramway station, 2 tracks each |

| Trains (daily): |

78 long-distance 440 regional |

Public transportation

The station is an interchange point for the Mainz tramway network, and an important bus junction for the city and region (RNN, ORN and MVG).

Cycling

Mainz offers a wide array of bicycle transportation facilities and events, including several miles of on-street bike lanes. The Rheinradweg (Rhine Cycle Route) is an international cycle route, running from the source to the mouth of the Rhine, traversing four countries at a distance of 1,300 km (810 mi). Another cycling tour runs towards Bingen and further to the Middle Rhine, a UNESCO World Heritage Site (2002).[31]

Air transportation

Mainz is served by Frankfurt Airport, the busiest airport by passenger traffic in Germany by far, the third busiest in Europe and the ninth busiest worldwide in 2009. Located about 10 miles (16 kilometres) east of Mainz, it is connected to the city by an S-Bahn line.[32]

The small Mainz Finthen Airport, located just 3 miles (5 km) southwest of Mainz, is used by general aviation only. Another airport, Frankfurt-Hahn Airport located about 50 miles (80 km) west of Mainz, is served by a few low-cost carriers.[32]

Notable people

- List of people related to Mainz

- Archbishops of Mainz

- List of mayors of Mainz

International relations

Mainz is twinned with:[33]

Alternative names

Mainz has a number of different names in other languages and dialects. In Latin it is known as Mogontiacum or Moguntiacum and, in the local West Middle German dialect, it is Määnz or Meenz. It is known as Mayence in French, Magonza in Italian, Maguncia in Spanish, Mogúncia in Portuguese, Moguncja in Polish, Magentza (מגנצא) in Yiddish, and Mohuč in Czech and Slovakian.

Before the 20th century, Mainz was commonly known in English as Mentz or by its French name of Mayence. It is the namesake of two American cities named Mentz.

See also

- Johann Fust

- Johannes Gutenberg

- Peter Schöffer, apprentice of Gutenberg and early printer

Notes and references

- "Bevölkerungsstand 2018 - Gemeindeebene". Statistisches Landesamt Rheinland-Pfalz (in German). 2019.

- Landeshauptstadt Mainz. "Einwohner_nach_Stadtteilen" (PDF) (in German). Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- Olaf Höckmann: Mainz als römische Hafenstadt. p. 87–106. in: Michael J. Klein (editor): Die Römer und ihr Erbe. Fortschritt durch Innovation und Integration. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2003, ISBN 3-8053-2948-2.

- "Mainz historic weather averages". Intellicast. June 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- The earliest certain evidence of the existence of Mogontiacum is the account of the death and funeral of Nero Claudius Drusus, brother of the future emperor, Tiberius, given in Suetonius' life of Drusus. Few leaders have been as loved and as popular as Drusus. He fell from his horse in 9 BC, contracted gangrene and lingered several days. His brother Tiberius reached him in just a few days riding post-horses over the Roman roads and served as the chief mourner, walking with the deceased in a funeral procession from the summer camp where he had fallen to Mogontiacum, where the soldiers insisted on a funeral. The body was transported to Rome, cremated in the Campus Martis and the ashes placed in the tomb of Augustus, who was still alive, and wrote poetry and delivered a state funeral oration for him. If Drusus founded Mogontiacum the earliest date is the start of his campaign, 13 BC. Some hypothesize that Mogontiacum was constructed at one of two earlier opportunities, one when Marcus Agrippa campaigned in the region in 42 BC or by Julius Caesar himself after 58 BC. Lack of evidence plays a part in favoring 13 BC. No sources cite Mogontiacum before 13 BC, no legions are known to have been stationed there, and no coins survive.

- von Elbe, Joachim (1975). Roman Germany: a guide to sites and museums. Mainz: P. von Zabern. p. 253.

- A second hypothesis suggests that Moguns was a wealthy Celt whose estate was taken for the fort and that a tax district was formed on the area parallel to other tax districts with a -iacum suffix (Arenacum, Mannaricium). There is no evidence for this supposedly wealthy man or his estate, but there is plenty for the god. According to Carl Darling Buck in Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin, -yo- and -k- are general Indo-European formative suffices and are not related to taxes. As the loyalty of the Vangiones was unquestioned and Drusus was campaigning over the Rhine, it is unlikely Mogontiacum would have been built to collect taxes from the Vangiones, who were not a Roman municipium.

- "Mainz, temple of Isis – Livius".

- "Isis-Tempel in Mainz".

- Michael Kulikowski, "Barbarians in Gaul, Usurpers in Britain" Britannia 31 (2000:325–345).

- Link

- Rosamond McKitterick, The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, (Longman Group, 1999), 229.

- Tuchman, Barbara Wertheim. A distant mirror. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-307-29160-8. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- de:Neue Synagoge Mainz

- Jean-Denis G.G. Lepage (2009). French Fortifications, 1715-1815: An Illustrated History. McFarland. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-7864-5807-3.

- Stanton, Shelby, World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939–1946, Stackpole Books (Revised Edition 2006), p. 164

- original text of Kœnig's order No. 57 Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine; as can be found on Landeshauptarchiv Rheinland-Pfalz (main-archive of Rhineland-Palatinate) Archived 24 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- History of Mainz Cathedral

- Aerial view Archived 8 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine of the total destruction from the repeated US & RAF bombing raids on the city; Photographer: Margaret Bourke-White.

- Aerial view Archived 17 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine of bomb-damaged theater, St. Quintins church, St. Johannis church and old university after an Allied air attack.

- Aerial view of Mainz-Neustadt and the port of Mainz for Life magazine

- Eric Paul Mumford: CIAM Discourse on Urbanism 1928–1960 p. 159

- Jeffry M. Diefendorf: In the Wake of War: The Reconstruction of German Cities After World War 2 p. 357

- Plan for the reconstruction of the German city of Mainz by Marcel Lods, 1947 in: Carl Fingerhuth: Learning from China: The Tao Of The City p. 59

- "ASC Theresianum Mainz Basketball |". Asc-theresianum-mainz.de. 13 April 2018.

- "Universitäts Sportclub Mainz: USC Mainz".

- Peter H. Eisenhuth in der Mainzer Rhein-Zeitung vom 9. September 2009

- Basketball: Cup Winner' Cup 1971–72 – First Round USC Mainz. Website Linguasport – Sport History and Statistics. Abgerufen am 4. Juni 2012.

- Culture and History (from the Mainz city council website. Accessed 10 February 2008.)

- "Great Wine Capitals".

- "Rhine Cycle Route". Euregio Rhine-Waal. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- "How to get to Mainz". Landeshauptstadt Mainz.

- "Partnerstädte". mainz.de (in German). Mainz. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

Sources

- Hope, Valerie. Constructing Identity: The Roman Funerary Monuments of Aquelia, Mainz and Nîmes; British Archaeological Reports (16. Juli 2001) ISBN 978-1-84171-180-5

- Imhof, Michael and Simone Kestin: Mainz City and Cathedral Guide. Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2004. ISBN 978-3-937251-93-6

- Mainz ("Vierteljahreshefte für Kultur, Politik, Wirtschaft, Geschichte"), since 1981

- Saddington, Denis. The stationing of auxiliary regiments in Germania Superior in the Julio-Claudian period

- Stanton, Shelby, World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939–1946 (Revised Edition, 2006), Stackpole Books ISBN 978-0-8117-0157-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mainz. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mainz. |

- The official web site of the city of Mainz

- . Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- "Mainz", The Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.), New York: Encyclopædia Britannica, 1910, OCLC 14782424

- Duchhardt, Heinz: „Römer“ in Mainz. Ein Doppelporträt aus der Frühgeschichte der „neuen“ Mainzer Universität

.jpg)