Mackenzie River expedition

The Mackenzie River expedition of 1825–1827 was the second of three Arctic expeditions led by explorer John Franklin and organized by the Royal Navy. It had as its goal the exploration of the North American coast between the mouths of the Mackenzie and Coppermine rivers and the Bering Strait, in what is now present-day Alaska, Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut. Franklin was accompanied by George Back and John Richardson, both of whom he had previously collaborated with during the disastrous Coppermine expedition of 1819–1821. Unlike Franklin's previous expedition, this one was largely successful, and resulted in the mapping of more than 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) of new coastline[1] between the Kent Peninsula and Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, an area that until then had remained largely unexplored by Europeans.[2]

Background

The Northwest Passage, a supposed sea route to the Pacific Ocean by way of the Arctic Ocean, had long been sought by European explorers as a possible trade route to East Asia and the Indies. During the Age of Exploration, the presupposed existence of the passage motivated much of European exploration in North America. Beginning in the early 19th century, the Royal Navy, having expanded to unprecedented proportions during the Napoleonic Wars, turned much of its attention to the passage's discovery.[3] Under the influence of Sir John Barrow, the Royal Navy sponsored many Arctic expeditions, including those led by John Ross, William Edward Parry, James Clark Ross, and John Franklin. For the next fifty years, the Royal Navy dominated the Arctic seas.[4]

Franklin himself was at that point an experienced mariner, serving in the Royal Navy while in his teens, and having been present during the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. In 1819, he was chosen to lead an expedition whose intention was to map the northern coast of the North American continent eastwards from the mouth of the Coppermine River. The Coppermine expedition was by any objective standard a disaster; Franklin completely failed in his goal of mapping a sufficient portion of the Arctic coast, and half of his 22-strong party died over the course of the journey. In spite of the expedition's disappointing results, upon his return to Britain, Franklin was lauded as a hero and promoted post-captain in 1822. In the following year he began planning another expedition to the Arctic, with the intention of, this time, using the Mackenzie River as the expedition's primary route of travel.[5]

Franklin himself devised the expedition's itinerary; it was accepted by the Admiralty in autumn, 1823. In accordance with his official instructions, he was to first spend the summer of 1825 travelling to Great Bear Lake via standard trading routes, where the party's winter quarters would have been constructed. Beginning in spring of 1826, Franklin was to descend the Mackenzie River to its mouth, where he would then split the party. A smaller detachment, led by Richardson, was to map the intermediate coast between the Mackenzie and Coppermine Rivers. Franklin himself was to travel westwards along the coast with the ultimate goal of reaching Icy Cape, the northern terminus of the Bering Sea. From there, Franklin would have the choice of either rendezvousing with HMS Blossom under the command of Frederick William Beechey or returning to the party's winter quarters at Great Bear Lake. Should he rendezvous with Beechey, Franklin would be conveyed either to the Sandwich Islands (now the Hawaiian Islands) or Canton, whereupon he would make his own way back to England.[6]

Preparations

In spite of the poor outcome of his previous expedition, Franklin had learned several key lessons that would lead to the future success of the Mackenzie River expedition. In Franklin's mind, the weak point of the Coppermine expedition was its dependency on outside help. His preparations were not completed sufficiently in advance, and he relied far too much on fur traders, voyageurs, and First Nations People, all of whom were far less forthcoming than anticipated. Applying this knowledge to his new expedition, Franklin sought to place greater trust in British naval personnel and, most critically, to bring sufficient supplies for the duration of the journey. The recent union of the North West Company and Hudson Bay Company, and resulting cessation of the companies' near-constant state of conflict also meant that any anticipated assistance would be much more likely to materialize.[7]

Supplies were ferried from York Factory to the continent's interior beginning in 1824. While still in Britain, Franklin oversaw the construction of the company's vessels. Although canoes of birch-bark were the de facto standard for travel along North America's internal waterways, Franklin judged them unfit for navigation in the open waters of the Arctic Ocean. He therefore commissioned the construction of three boats built of ash and mahogany, the largest of which was 8 metres (26 ft) in length and was capable of carrying 2.7 tonnes (6,000 lb) of baggage. Navigation instruments included a sextant, altimeters and a telescope. Supplies included tobacco, alcohol, tents, books, paper, fishing implements, blankets, clothing, guns, knives and hatchets; much of the company's supplies were intended to be traded with the local First Nations communities.[8]

Events of the expedition

Departure and first season

Franklin and the other naval officers, including Back and Richardson, departed Liverpool on 16 February 1825. Landing in New York City on 15 March, they then followed standard travelling routes through New York State, across the Niagara River and Lake Ontario, then through Upper Canada to Fort William on the shores of Lake Superior. After traversing numerous lakes and river systems, the party arrived at Cumberland House on the Saskatchewan River on 15 June. From there, they reached Methye Portage, mostly by way of the Churchill River system. Simultaneously, most of the expedition's supplies were sent from York Factory on Hudson Bay up the Hayes River, reaching the officers at Methye Portage on 29 June.

The party descended the Clearwater and Athabasca Rivers, arriving at Fort Chipewyan on 15 July. The party's expeditious pace can be attributed to their intense rowing efforts: during their last push to Great Slave Lake, they had been paddling for thirty-six of the thirty-nine preceding hours.[9] At Fort Resolution, Franklin met with Keskarrah and Humpy of the Coppermine Indians, the latter of whom was the brother of Franklin's friend and former ally Akaitcho. After coasting the southern shore of Great Slave Lake, the party reached the headwaters of the Mackenzie River on 3 August, which would thereafter be their route to the Arctic Ocean.

The party began their descent of the Mackenzie, reaching its junction with the "River of the Mountains" (likely the Liard River) on 4 August. Fort Norman was reached on 7 August, with the group having traveled 423 kilometres (263 mi) in three days.[10] At Fort Norman, realizing that their speedy pace afforded them additional time for exploration, Franklin opted to embark on a preliminary reconnaissance to the mouth of the Mackenzie River, while the rest of the party would continue to Great Bear Lake to oversee the construction of their winter quarters. The goal of this venture was primarily to find the best route to the sea, in addition to establishing friendly relations with the native Inuit.[11] Joined by Admiralty Mate E.N. Kendall and an Inuit interpreter, Franklin departed on 8 August.

During their descent they encountered several groups of First Nations, some of whom joined them for a portion of the journey. The delta of the Mackenzie was reached on 13 August, whereafter the party began exploring the archipelago of islands surrounding the river's mouth. Most of their early navigation of the sea was plagued by intense fog that occluded astronomical observation. After completing their early charting, the group returned to the Mackenzie River proper, reaching Fort Franklin (modern day Délı̨nę) on Great Bear Lake on 5 September. Over the course of the 1825 season the party had traveled 9,339 kilometres (5,803 mi).[12]

Winter

The winter of 1825–1826 was relatively uneventful. On 8 September, Franklin dispatched two men to Great Slave Lake to convey an account of the expedition's progress and to pick up letters sent from the Crown. Supplies were provided by the Chipewyan and Dog-Rib Indians. With October came the first frosts and snow; it was at this time, just before ice began to form on the lake, that fishing was most productive. According to Franklin, several hundred fish were caught daily,[13] most of which were frozen until the following spring.

Those at Fort Franklin were frequently visited by the local First Nations. On one such occasion, on 18 December, the wife of one of the Dog-Rib hunters brought her young girl to the fort, seeking advice on the girl's sickly condition. In spite of the Europeans' efforts, the girl perished, bringing great grief to the mother. The First Nations and Europeans celebrated Christmas together on 25 December. On 1 January, the coldest temperature of the season, −45 °C (−49 °F), was recorded. The month of February brought anxiety to the party as their fishing output greatly decreased. The group's dried meat had since been expended, and the scant diet of fish caused several among the them to suffer from diarrhea.

As recorded in Franklin's journal, during the winter of 1825–1826, to pass the time, the men played a game very similar to modern ice hockey. In a separate entry, Franklin noted that "skating" was among the winter "amusements" enjoyed by his men. Whether or not the use of ice skates were combined with the game is not known; if the two were combined, this would make Fort Franklin (Délı̨nę) the earliest documented location where ice hockey was played, and also the first known use of the word "hockey" in reference to the modern-day sport.[14]

The ice on Great Bear Lake began breaking up on 23 May, but with this came the constant threat of mosquitoes, which Franklin called "vigorous and tormenting".[15] As winter ended, the party made a more concentrated effort to chart the coastline of Great Bear Lake. The most extensive of these explorations was conducted by Richardson and Kendall, lasting from 10 April–1 May. Franklin at this point grew displeased with the constant presence of the Dog-Rib Indians, claiming that they "continued hanging about the fort, and their daily drumming and singing over the sick, the squalling of the children, and bawling of the men and women, proved no small annoyance."[16] With the beginning of June, Franklin began more intensely planning the party's voyage to the coast. The boats the company had been constructing over the course of the winter were tested on 15 June. Supplies and men were then divided between the western and eastern detachment, and after final preparations were made, the party departed from Fort Franklin on the summer solstice of 1826.

Spring and the parties split

The expedition's plans for the coming summer were ambitious. Franklin, leading the western detachment, aimed to get as far as Icy Cape, which had previously been visited by James Cook in 1778. Richardson's journey would involve coasting the shore of the ocean as far east as the mouth of the Coppermine River. He would then ascend the river and cross overland to Great Bear Lake, ideally arriving at Fort Franklin before the onset of winter.

The party made quick progress in descending the Mackenzie River, reaching its delta by early July. The western detachment was to consist of two boats, Lion and Reliance, commanded by Franklin and Back, respectively. The eastern detachment consisted of the boats Dolphin and Union. In the early morning of 4 July, the parties split.

Western detachment

The western detachment quickly faced difficulty at the hands of the Inuit. When the boats became grounded due to the river's shallowness, Franklin, while observing the location's longitude, discovered a nearby Inuit settlement. After instructing Back and the others to be prepared to take up arms should the Inuit prove hostile, Franklin departed for the camp, alongside the party's interpreter, Augustus. The settlement, which contained in excess of 250 individuals, initially greeted the expeditionaries with hesitance.[17] When Franklin later explained the benefit to their people of the putative sea route known as the Northwest Passage, they became friendly. Soon after, however, the Inuit, desiring the party's cargo, plundered Lion and Reliance. After an altercation lasting several hours, the two boats departed; Franklin commanded that none of the Inuit follow them under penalty of being shot. He later designated the area where the conflict had occurred as Pillage Point.[18]

For the rest of the season, much of the group's voyage was impeded by poor weather and sea ice. On 9 July, the group once again came in contact with the Inuit; this encounter was much more cordial. Franklin inquired as to the usual date of ice breakup and the groups exchanged gifts. According to Franklin, the Inuit group, who numbered 48, had a high proportion of elders, all of whom were highly active and appeared in excellent health. Nearly all suffered from some degree of snowblindness. When told of the Europeans' previous encounter, the Inuit condemned the attack.[19]

On 15 July, the mouth of the Babbage River was reached; soon after, Herschel Island came into view. On 17 July, the party stepped foot on the island, where they came into contact with more Inuit. Western travel along the Arctic coast was arduous: temperatures seldom exceeded 6 °C (43 °F), and gusts of wind frequently upended the expeditionaries' tents, making sheltering from the rain difficult. The constant fog obscured visibility, and the mosquitoes were described by Franklin as "torturous". At one point, Augustus fell into a fit of hypothermia after rushing into an icy lake in pursuit of a reindeer. He was given blankets and chocolate to warm up, but by the next morning still felt pain in his limbs.[20]

By 30 July, the party had entered the waters of the modern-day state of Alaska; Brownlow Point was reached on 5 August. In the succeeding weeks, Franklin grew hesitant to continue pursuing the expedition's goal of reaching Icy Cape. On 16 August, realizing that summer was coming to an end and the navigability of the rest of the party's route would be threatened by increasingly poor conditions, Franklin decided they would turn back towards the Mackenzie's mouth. Unbeknownst to him however, an exploratory party of Beechey's vessel lay only 257 kilometres (160 mi) to the west, which, under the party's average pace, could have been reached in less than a week. According to Franklin, had he known that Beechey's vessel was a mere six days' pursuit away, "no difficulties, dangers, or discouraging circumstances, should have prevailed" on him to convene with Beechey.[21] He was, however, oblivious to Beechey's proximity, and opted to return to the Mackenzie.

The journey east was relatively uneventful, but sea ice and wind continued to pose a serious threat to the expeditionaries. The party landed on Herschel Island again on 26 August. Encounters with Inuit occurred almost daily; on 29 August, Franklin was informed by a group of Inuit that Richardson's party had been seen clearing the Mackenzie River delta and had narrowly escaped another attempt by the Inuit to pillage their boats. He was later alarmed by a group of Inuit who rushed into the party's camp and informed them that a rival Inuit group was en route with the express intent of massacring the party and stealing their possessions. This group, termed the 'Mountain Indians' by Franklin, allegedly had planned to await their likely return to the mouth of the Mackenzie River. Under the pretense of helping the Europeans navigate the river, the Mountain Indians would then stave in their boats, making them unfit for escape to deeper waters; then a larger group would rush out of a predesignated hiding spot and attack. Franklin was cautioned by the Inuit to thenceforth only camp on islands that were out of gunshot range.[22] He later surmised that the Mountain Indians had been armed by trades conducted with the Russians, who were ostensibly prohibited from trading with any Inuit groups.

By September, the party was ascending the Mackenzie River, and on 4 September had reached Point Separation, where the two detachments had originally split. They recovered a small depot of supplies, stowed by the party the previous July, before pressing on. The mouth of the Great Bear River was reached on 16 September; five days later, Fort Franklin was reached. Over the course of their journey, the western party had traveled a total distance of 3,296 kilometres (2,048 mi) in 80 days, with an average distance of about 41 kilometres (25 mi) per day.

Eastern detachment

Consisting of twelve individuals, the eastern detachment proceeded down the Mackenzie, and eventually to open ocean. Encounters with the Inuit were relatively amicable, with the task of interpretation given to the group's Inuit companion, Ooligbuck.

After traversing the maze of islands that comprise the delta of the Mackenzie, open sea was reached on 7 July. That same day, a band of Inuit were encountered. Quelling their initial fears by presenting gifts, Richardson established relations with the group, but found their disposition impolite.[23] Ooligbuck, apparently distrusting the band, urged Richardson to depart; upon doing so, the party was trailed by the Inuit. These encounters remained almost constant until 20 July, when the last group of Inuit were seen before the party reached the Coppermine.

The following days were spent rounding the highly indented coastline; progress was impeded by the constant presence of sea ice. On 4 August, a large northerly landmass came into view, which Richardson termed Wollaston Land. In reality, this land was actually a southerly protuberance of Victoria Island, one of the largest islands in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. This was the first time a European had laid eyes on the island. Coronation Gulf was reached on 6 August, whereupon the group turned southwards until they reached the mouth of the Coppermine. It was at this point that Richardson crossed into territory already mapped during Franklin's previous expedition.

The party reached the mouth of the Coppermine River on 8 August, and the next day began ascending the river. The river was at that point running extremely low, occasionally to the point that it hindered the travel of their boats. After passing Bloody Falls, Richardson judged that the rest of the Coppermine's course was unfit for navigation by boat. He therefore decided that Dolphin and Union would be left behind and the group would carry on by foot. Each man was allotted 9 kilograms (20 lb) of pemmican, in addition to packages of macaroni, dry soup mix, chocolate, sugar, and tea. In addition, the group carried a portable boat; blankets; spare guns, shoes, and ammunition; fishing nets; kettles; and hatchets. When divided among the party, this load came to a weight of 33 kilograms (73 lb) per man. Richardson feared that carrying so much weight would prove too arduous, and assured the men that when sufficient progress was made they would halt and examine the necessity of carrying certain items.[24] All that was not carried by the party was stowed in tents marked with a Union Jack for the use of a future expeditionary force.

The march to Great Bear Lake began on 10 August. Richardson planned to follow the Coppermine as far as its junction with the Copper Mountains. From there they would hike in more or less a straight line until reaching the Dease River, which they would then descend to its mouth at Great Bear Lake. Many among the party were unaccustomed to carrying such heavy loads, but upon examining the group's stocks, Richardson found little that he considered superfluous enough to discard. He eventually resolved to abandon the portable boat and five of the group's rifles, reducing each man's load by 7 kilograms (15 lb). Still, the group seldom traveled at a pace of more than 3 kilometres per hour (1.9 mph).

In spite of their reduced loads, many among the party were exhausted by the end of each day.[25] Richardson attributed much of their exertion to the frequent change of elevation and the spongy, wet ground and resulting absence of secure footing. The party grew more accommodated to their loads in the succeeding days and soon established a more productive pace.

In the night of 15 August the party encountered a group of First Nations who led them to the headwaters of the Dease River. Soon after, a range of hills distinct to the north shore of Great Bear Lake came into view, and the lake itself was spotted on 18 August. From that point onward, Richardson was to wait for a scout from Fort Franklin who had been directed to depart from the fort on 6 August to the mouth of the Dease River and wait there for Richardson's party. After sending out hunting excursions to enlarge the expedition larder in preparation for their push to Fort Franklin, on 21 August, Richardson and the scouting party were united. After paddling along the coast of Great Bear Lake, Fort Franklin was reached on 1 September, nearly two weeks before the western detachment.

The eastern detachment had traveled 3,197 kilometres (1,987 mi) over the course of 60 days, amounting to an average of 53 kilometres (33 mi) per day. A total of 1,452 kilometres (902 mi) of new coastline had been charted over the course of the journey.[26]

Second winter and departure

During the party's absence from Fort Franklin, those still inhabiting the dwelling were directed to make repairs, which were completed by the time Franklin arrived. Upon his arrival, however, Franklin became concerned at the depletion of the fort's food stores, and dispatched Kendall to requisition some food and other supplies from Fort Norman. Kendall returned to the fort on 8 October, carrying an abundance of food and other supplies, which were of particular benefit to the eastern detachment, who had been forced to sacrifice much of their equipment during their overland crossing between the Coppermine and Dease Rivers.[27]

The party's second winter offered few events of note. By mid-November, ice on the Great Bear Lake rendered it unnavigable. By early January, temperatures dipped to −47 °C (−53 °F), and by February, to −50 °C (−58 °F). The fort's larder at that point consisted of some tens of thousands of fish and nearly 11 tonnes (24,000 lb) of meat.[28] Franklin endeavored to depart from the fort much earlier than in the previous season. He quit the fort on 20 February, carrying most of his supplies, including all of the expedition's charts, journals, and drawings, on a sledge, while Back was to remain at the fort until the breakup of the ice, after which he would proceed to York Factory and thence to England on an HBC ship.

Franklin and his company traveled southwards through the taiga, arriving at Fort Chipewyan on 12 April and then Cumberland House on 18 June. It was there that Franklin and Augustus were to split, with the latter shedding tears at their parting and requesting to be informed of any other expedition to the Arctic that he could join.[29] They reached New York in August, and on 1 September Franklin departed from North America on a packet ship bound for Liverpool, which he reached on 26 September, while Back and the other officers arrived in Britain in October. Franklin's second expedition had thereafter concluded.

Aftermath

Upon his returned to Britain, Franklin was lauded as a hero.[30] In 1829 he was knighted by George IV, and later appointed Knight Commander of the Royal Guelphic Order and a Knight of the Greek Order of the Redeemer.[31] Although Back had been appointed commander in 1825, following his return to Britain, he was unable to find appointment to a ship, and was unemployed until 1833.

Over the course of the expedition, Franklin and his associates had traveled nearly 22,000 kilometres (14,000 mi)[32] and mapped half of the continent's northern coast.[33] This was a sharp contrast to Franklin's previous expedition, where only 800 kilometres (500 mi) had been explored before the party was forced to turn back.

Franklin himself later wrote of the contrast between this expedition and his previous one. During the breaking of the party at Point Separation, he realized the contrast between his situation and the previous expedition, writing that "it was impossible not to be struck with the difference between our present complete state of equipment and that on which we had embarked on our former disastrous voyage. Instead of a frail bark canoe, and a scanty supply of food, we were now about to commence the sea voyage in excellent boats, stored with three months' provision."[34]

Franklin was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen's Land in 1837, leaving this post after six years. Given that less than 500 kilometres (310 mi) of Arctic coastline remained unmapped, Franklin, then 59 years old, was appointed to lead another expedition in 1845. The Northwest Passage expedition departed England in 1845 aboard the ships HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. In the autumn of 1846, the vessels became icebound somewhere in Victoria Strait, and Franklin and all 128 of his men were lost. During the Admiralty's inquest of Franklin's lost expedition, of which Back was a member, several search parties were dispatched, all of which were ultimately unsuccessful. The wrecks of Erebus and Terror were found[35] off King William Island in 2014 and 2016, respectively.

Preceding discoveries

Prior to Franklin's second expedition, the mouth of the Mackenzie River had only been seen on one occasion by Europeans. In 1789, Scottish explorer Alexander Mackenzie descended the river, hoping that it would lead to the Pacific Ocean.[36] Under the employ of the North West Company, Mackenzie spent the summer of 1789 descending the river and reached its mouth on 14 July. In Mackenzie's mind, having reached the wrong ocean, he turned back in disappointment and returned to Britain, where his efforts were not widely recognized.[37] Mackenzie later led the first overland crossing of North America, reaching the western coast of British Columbia in 1793.[38]

In 1771 Samuel Hearne crossed overland from Hudson Bay, reaching the source of the Coppermine River in July. He descended the river down to Coronation Gulf, marking the first time a European had reached the Arctic Ocean by land.

During his third voyage, James Cook mapped much of the western coast of North America, including Alaska's eponymous Cook Inlet. He reached Icy Cape, the ultimate goal of Franklin's western detachment, in August 1778. It was named by Cook for the large amounts of ice along the cape's coast.[39]

See also

- The Coppermine expedition, Franklin's previous overland expedition known for its abysmal results

- John Franklin, George Back, and John Richardson, the primary naval personnel of the expedition

- Prudhoe Bay and the Kent Peninsula, the boundaries of the extent of the expedition's coastal mapping

- The Northwest Passage

- Arctic exploration

- Franklin's lost expedition, which ultimately ended up being his demise

References

- Fleming, Fergus (1998). Barrow's Boys. Granta Books.

- Holland, Clive A. (1972). "BACK, Sir GEORGE". Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- Fleming, Fergus (1998). Barrow's Boys. Granta Books. p. 30.

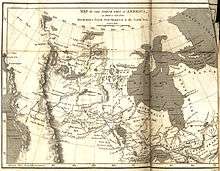

- "Map Shewing The Discoveries made by British Officers in the Arctic Regions from the Year 1818 to 1826". princeton.edu. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- Holland, Clive A. (1988). "FRANKLIN, Sir JOHN". Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. xxi.

- Holland, Clive A. (1988). "FRANKLIN, Sir JOHN". Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. xii.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 29.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 35.

- Rudmose-Brown, R.N. (1970). Encyclopedia Arctica 15: Biographies. p. 8.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 60.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 67.

- Boswell, Randy (17 September 2011). "Deline, NWT: The 'birthplace' of hockey?". NunatsiaqOnline. Nunatsiaq News. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 83.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 83.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 97.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 102.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 111.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 111.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 145.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 154.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 167.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 223.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 225.

- Dawson, L.S. (1830). Memoirs of Hydrography. Google Books: H.W. Keay. p. 105.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 239.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 246.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 258.

- Neatby, Leslie H.; Mercer, Keither (6 April 2018). "Sir John Franklin". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- "Address". The Hobart Town Courier (Tas: 1827–1839). May 26, 1837. p. 3 – via NLA Australian Newspapers.

- Franklin, John (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Carey, Lea, and Carey. p. 262.

- Holland, Clive A. (1972). "BACK, Sir GEORGE". Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Franklin: 1825-1827". princeton.edu. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- Watson, Paul (12 September 2016). "Ship found in Arctic 168 years after doomed Northwest Passage attempt". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1801). Voyages from Montreal Through the Continent of North America. A.S. Barnes and Company.

- Lamb, W. Kaye (1983). "MACKENZIE, Sir ALEXANDER". biographi.ca. University of Toronto. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- Hayes, Derek (2009). First Crossing: Alexander Mackenzie, His Expedition Across North America, and the Opening of the Continent. D&M Publishers. pp. 211–224. ISBN 978-1-926706-59-7. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 164.

Bibliography

- Dawson, L. S., ed. (1883). Memoirs of Hydrography. 1. Eastbourne: Henry W. Keay. OCLC 1042130838.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hayes, D. (2009). First Crossing: Alexander Mackenzie. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 9781926706597.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fleming, F. (1998). Barrow's Boys: a Stirring Story Of Daring, Fortitude, And Outright Lunacy. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 9780802197559.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Franklin, J.; Richardson, J. (1828). Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea. Philadelphia: Carey, Lea, and Carey. OCLC 768324276.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)