Photokeratitis

Photokeratitis or ultraviolet keratitis is a painful eye condition caused by exposure of insufficiently protected eyes to the ultraviolet (UV) rays from either natural (e.g. intense sunlight) or artificial (e.g. the electric arc during welding) sources. Photokeratitis is akin to a sunburn of the cornea and conjunctiva, and is not usually noticed until several hours after exposure. Symptoms include increased tears and a feeling of pain, likened to having sand in the eyes.

| Photokeratitis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

The injury may be prevented by wearing eye protection that blocks most of the ultraviolet radiation, such as welding goggles with the proper filters, a welder's helmet, sunglasses rated for sufficient UV protection, or appropriate snow goggles. The condition is usually managed by removal from the source of ultraviolet radiation, covering the corneas, and administration of pain relief. Photokeratitis is known by a number of different terms including: snow blindness, arc eye, welder's flash, bake eyes, corneal flash burns, sand man's eye, flash burns, niphablepsia, potato eye, or keratoconjunctivitis photoelectrica.

Signs and symptoms

Common symptoms include pain, intense tears, eyelid twitching, discomfort from bright light,[1] and constricted pupils.

Cause

Any intense exposure to UV light can lead to photokeratitis.[2] Common causes include welders who have failed to use adequate eye protection such as an appropriate welding helmet or welding goggles. This is termed arc eye, while photokeratitis caused by exposure to sunlight reflected from ice and snow, particularly at elevation, is commonly called snow blindness.[3] It can also occur due to using tanning beds without proper eyewear. Natural sources include bright sunlight reflected from snow or ice or, less commonly, from sea or sand.[4] Fresh snow reflects about 80% of the UV radiation compared to a dry, sandy beach (15%) or sea foam (25%). This is especially a problem in polar regions and at high altitudes,[3] as with every thousand feet (approximately 305 meters) of elevation (above sea level), the intensity of UV rays increases by four percent.[5]

Diagnosis

Fluorescein dye staining will reveal damage to the cornea under ultraviolet light.[6]

Prevention

Photokeratitis can be prevented by using sunglasses or eye protection that transmits 5–10% of visible light and absorbs almost all UV rays. Additionally, these glasses should have large lenses and side shields to avoid incidental light exposure. Sunglasses should always be worn, even when the sky is overcast, as UV rays can pass through clouds.[7]

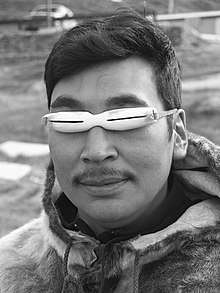

The Inuit, Yupik, and other Arctic peoples carved snow goggles from materials such as driftwood or caribou antlers to help prevent snow blindness. Curved to fit the user's face with a large groove cut in the back to allow for the nose, the goggles allowed in a small amount of light through a long thin slit cut along their length. The goggles were held to the head by a cord made of caribou sinew.[8]

In the event of missing sunglass lenses, emergency lenses can be made by cutting slits in dark fabric or tape folded back onto itself.[9] The SAS Survival Guide recommends blackening the skin underneath the eyes with charcoal (as the ancient Egyptians did) to avoid any further reflection.[10][11]

Treatment

The pain may be temporarily alleviated with anaesthetic eye drops for the examination; however, they are not used for continued treatment,[12] as anaesthesia of the eye interferes with corneal healing, and may lead to corneal ulceration and even loss of the eye.[13] Cool, wet compresses over the eyes and artificial tears may help local symptoms when the feeling returns. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) eyedrops are widely used to lessen inflammation and eye pain, but have not been proven in rigorous trials. Systemic (oral) pain medication is given if discomfort is severe. Healing is usually rapid (24–72 hours) if the injury source is removed. Further injury should be avoided by isolation in a dark room, removing contact lenses, not rubbing the eyes, and wearing sunglasses until the symptoms improve.[3]

See also

- Actinic conjunctivitis

- Albedo

- Glare (vision)

- Over-illumination

- Health effects of sun exposure

- Selective yellow

- Eye black

- Solar Retinopathy

References

- "Arc eye – General Practice Notebook". 2007-03-25. Archived from the original on 2007-03-25. Retrieved 2012-02-07.

- Porter, Daniel (February 16, 2019). "What is Photokeratitis — Including Snow Blindness?". American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- Brozen, Reed; Christian Fromm (February 4, 2008). "Ultraviolet Keratitis". eMedicine. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- "Snow blindness". General Practice Notebook. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- "Sun Safety". University of California, Berkeley. April 2005. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- Reed Brozen (15 April 2011). "Ultraviolet Keratitis". Medscape.com. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Butler Jr, Frank. "Base Camp MD – Guide to High Altitude Medicine". Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- Mogens Norn (1996). Eskimo Snow Goggles in Danish and Greenlandic Museums, Their Protective and Optical Properties. Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-87-635-1233-6.

- Henry, Jeff. Survive: Snow Country. p. 107.

- Wiseman, John (2004). "Climate & Terrain". SAS Survival Guide: How to survive in the wild, in any climate on land or at sea. Harper Collins. p. 45. ISBN 0-00-718330-5.

- "Egyptian Make Up". King-tut.org.uk. 2007-05-29. Archived from the original on 2012-01-26. Retrieved 2012-02-07.

- "Photokeratitis (Ultraviolet [UV] burn, Arc eye, Snow Blindness)". The College of Optometrists. April 4, 2018. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- Khakshoor, Hamid (October 2012). "Anesthetic keratopathy presenting as bilateral Mooren-like ulcers". Clinical Ophthalmology. 6: 1719–1722. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S36611. PMC 3484722. PMID 23118524.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |