Lyme disease

Lyme disease, also known as Lyme borreliosis, is an infectious disease caused by the Borrelia bacterium which is spread by ticks.[2] The most common sign of infection is an expanding red rash, known as erythema migrans, that appears at the site of the tick bite about a week after it occurred.[1] The rash is typically neither itchy nor painful.[1] Approximately 70–80% of infected people develop a rash.[1] Other early symptoms may include fever, headache and tiredness.[1] If untreated, symptoms may include loss of the ability to move one or both sides of the face, joint pains, severe headaches with neck stiffness, or heart palpitations, among others.[1] Months to years later, repeated episodes of joint pain and swelling may occur.[1] Occasionally, people develop shooting pains or tingling in their arms and legs.[1] Despite appropriate treatment, about 10 to 20% of people develop joint pains, memory problems, and tiredness for at least six months.[1][5]

| Lyme disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Lyme borreliosis |

| |

| An adult deer tick (most cases of Lyme are caused by nymphal rather than adult ticks) | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Expanding area of redness at the site of a tick bite, fever, headache, tiredness[1] |

| Complications | Facial nerve paralysis, arthritis, meningitis[1] |

| Usual onset | A week after a bite[1] |

| Causes | Borrelia spread by ticks[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, tick exposure, blood tests[3] |

| Prevention | Prevention of tick bites (clothing the limbs, DEET), doxycycline[2] |

| Medication | Doxycycline, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime[2] |

| Frequency | 365,000 per year[2][4] |

Lyme disease is transmitted to humans by the bites of infected ticks of the genus Ixodes.[6] In the United States, ticks of concern are usually of the Ixodes scapularis type, and must be attached for at least 36 hours before the bacteria can spread.[7][8] In Europe, ticks of the Ixodes ricinus type may spread the bacteria more quickly.[8][9] In North America, the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia mayonii cause Lyme disease.[2][10] In Europe and Asia, Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii are also causes of the disease.[2] The disease does not appear to be transmissible between people, by other animals, or through food.[7] Diagnosis is based upon a combination of symptoms, history of tick exposure, and possibly testing for specific antibodies in the blood.[3][11] Blood tests are often negative in the early stages of the disease.[2] Testing of individual ticks is not typically useful.[12]

Prevention includes efforts to prevent tick bites such as by wearing clothing to cover the arms and legs, and using DEET-based insect repellents.[2] Using pesticides to reduce tick numbers may also be effective.[2] Ticks can be removed using tweezers.[13] If the removed tick was full of blood, a single dose of doxycycline may be used to prevent development of infection, but is not generally recommended since development of infection is rare.[2] If an infection develops, a number of antibiotics are effective, including doxycycline, amoxicillin, and cefuroxime.[2] Standard treatment usually lasts for two or three weeks.[2] Some people develop a fever and muscle and joint pains from treatment which may last for one or two days.[2] In those who develop persistent symptoms, long-term antibiotic therapy has not been found to be useful.[2][14]

Lyme disease is the most common disease spread by ticks in the Northern Hemisphere.[15] It is estimated to affect 300,000 people a year in the United States and 65,000 people a year in Europe.[2][4] Infections are most common in the spring and early summer.[2] Lyme disease was diagnosed as a separate condition for the first time in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut.[16] It was originally mistaken for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.[16] The bacterium involved was first described in 1981 by Willy Burgdorfer.[17] Chronic symptoms following treatment are well described and are known as "post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome" (PTLDS).[14] PTLDS is different from chronic Lyme disease; a term no longer supported by the scientific community and used in different ways by different groups.[14][18] Some healthcare providers claim that PTLDS is caused by persistent infection, but this is not believed to be true because no evidence of persistent infection can be found after standard treatment.[19] A vaccine for Lyme disease was marketed in the United States between 1998 and 2002, but was withdrawn from the market due to poor sales.[2][20][21] Research is ongoing to develop new vaccines.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Lyme disease can affect multiple body systems and produce a broad range of symptoms. Not everyone with Lyme disease has all of the symptoms, and many of the symptoms are not specific to Lyme disease but can occur with other diseases, as well.

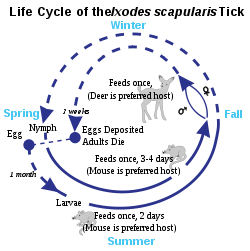

The incubation period from infection to the onset of symptoms is usually one to two weeks, but can be much shorter (days), or much longer (months to years).[26] Lyme symptoms most often occur from May to September, because the nymphal stage of the tick is responsible for most cases.[26] Asymptomatic infection exists, but occurs in less than 7% of infected individuals in the United States.[27] Asymptomatic infection may be much more common among those infected in Europe.[28]

Early localized infection

Early localized infection can occur when the infection has not yet spread throughout the body. Only the site where the infection has first come into contact with the skin is affected. The initial sign of about 80% of Lyme infections is an Erythema migrans (EM) rash at the site of a tick bite, often near skin folds, such as the armpit, groin, or back of knee, on the trunk, under clothing straps, or in children's hair, ear, or neck.[22][2] Most people who get infected do not remember seeing a tick or the bite. The rash appears typically one or two weeks (range 3–32 days) after the bite and expands 2–3 cm per day up to a diameter of 5–70 cm (median 16 cm).[22][2][23] The rash is usually circular or oval, red or bluish, and may have an elevated or darker center.[2][24][25] In about 79% of cases in Europe but only 19% of cases in endemic areas of the U.S., the rash gradually clears from the center toward the edges, possibly forming a "bull's eye" pattern.[23][24][25] The rash may feel warm but usually is not itchy, is rarely tender or painful, and takes up to four weeks to resolve if untreated.[2]

The EM (Erythema migrans) rash is often accompanied by symptoms of a viral-like illness, including fatigue, headache, body aches, fever, and chills, but usually not nausea or upper-respiratory problems. These symptoms may also appear without a rash, or linger after the rash disappears. Lyme can progress to later stages without these symptoms or a rash.[2]

People with high fever for more than two days or whose other symptoms of viral-like illness do not improve despite antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease, or who have abnormally low levels of white or red cells or platelets in the blood, should be investigated for possible coinfection with other tick-borne diseases, such as ehrlichiosis and babesiosis.[29]

Early disseminated infection

Within days to weeks after the onset of local infection, the Borrelia bacteria may spread through the lymphatic system or bloodstream. In 10-20% of untreated cases, EM rashes develop at sites across the body that bear no relation to the original tick bite.[22] Transient muscle pains and joint pains are also common.[22]

In about 10-15% of untreated people, Lyme causes neurological problems known as neuroborreliosis.[30] Early neuroborreliosis typically appears 4–6 weeks (range 1–12 weeks) after the tick bite and involves some combination of lymphocytic meningitis, cranial neuritis, radiculopathy and/or mononeuritis multiplex.[29][31] Lymphocytic meningitis causes characteristic changes in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and may be accompanied for several weeks by variable headache and, less commonly, usually mild meningitis signs such as inability to flex the neck fully and intolerance to bright lights, but typically no or only very low fever.[32] In children, partial loss of vision may also occur.[29] Cranial neuritis is an inflammation of cranial nerves. When due to Lyme, it most typically causes facial palsy impairing blinking, smiling, and chewing in one or both sides of the face. It may also cause intermittent double vision.[29][32] Lyme radiculopathy is an inflammation of spinal nerve roots that often causes pain and less often weakness, numbness, or altered sensation in the areas of the body served by nerves connected to the affected roots, e.g. limb(s) or part(s) of trunk. The pain is often described as unlike any other previously felt, excruciating, migrating, worse at night, rarely symmetrical, and often accompanied by extreme sleep disturbance.[31][33] Mononeuritis multiplex is an inflammation causing similar symptoms in one or more unrelated peripheral nerves.[30][29] Rarely, early neuroborreliosis may involve inflammation of the brain or spinal cord, with symptoms such as confusion, abnormal gait, ocular movements, or speech, impaired movement, impaired motor planning, or shaking.[29][31]

In North America, facial palsy is the typical early neuroborreliosis presentation, occurring in 5-10% of untreated people, in about 75% of cases accompanied by lymphocytic meningitis.[29][34] Lyme radiculopathy is reported half as frequently, but many cases may be unrecognized.[35] In European adults, the most common presentation is a combination of lymphocytic meningitis and radiculopathy known as Bannwarth syndrome, accompanied in 36-89% of cases by facial palsy.[31][33] In this syndrome, radicular pain tends to start in the same body region as the initial erythema migrans rash, if there was one, and precedes possible facial palsy and other impaired movement.[33] In extreme cases, permanent impairment of motor or sensory function of the lower limbs may occur.[28] In European children, the most common manifestations are facial palsy (in 55%), other cranial neuritis, and lymphocytic meningitis (in 27%).[31]

In about 4-10% of untreated cases in the U.S. and 0.3-4% of untreated cases in Europe, typically between June and December, about one month (range 4 days-7 months) after the tick bite, the infection may cause heart complications known as Lyme carditis.[36][37] Symptoms may include heart palpitations (in 69% of people), dizziness, fainting, shortness of breath, and chest pain.[36] Other symptoms of Lyme disease may also be present, such as EM rash, joint aches, facial palsy, headaches, or radicular pain.[36] In some people, however, carditis may be the first manifestation of Lyme disease.[36] Lyme carditis in 19-87% of people adversely impacts the heart's electrical conduction system, causing atrioventricular block that often manifests as heart rhythms that alternate within minutes between abnormally slow and abnormally fast.[36][37] In 10-15% of people, Lyme causes myocardial complications such as cardiomegaly, left ventricular dysfunction, or congestive heart failure.[36]

Another skin condition, found in Europe but not in North America, is borrelial lymphocytoma, a purplish lump that develops on the ear lobe, nipple, or scrotum.[38]

Late disseminated infection

After several months, untreated or inadequately treated people may go on to develop chronic symptoms that affect many parts of the body, including the joints, nerves, brain, eyes, and heart.

Lyme arthritis occurs in up to 60% of untreated people, typically starting about six months after infection.[22] It usually affects only one or a few joints, often a knee or possibly the hip, other large joints, or the temporomandibular joint.[29][39] There is usually large joint effusion and swelling, but only mild or moderate pain.[29] Without treatment, swelling and pain typically resolve over time but periodically return.[29] Baker's cysts may form and rupture. In some cases, joint erosion occurs.

Chronic neurologic symptoms occur in up to 5% of untreated people.[40] A peripheral neuropathy or polyneuropathy may develop, causing abnormal sensations such as numbness, tingling or burning starting at the feet or hands and over time possibly moving up the limbs. A test may show reduced sensation of vibrations in the feet. An affected person may feel as if wearing a stocking or glove without actually doing so.[29]

A neurologic syndrome called Lyme encephalopathy is associated with subtle memory and cognitive difficulties, insomnia, a general sense of feeling unwell, and changes in personality.[41] However, problems such as depression and fibromyalgia are as common in people with Lyme disease as in the general population.[42][43]

Lyme can cause a chronic encephalomyelitis that resembles multiple sclerosis. It may be progressive and can involve cognitive impairment, brain fog, migraines, balance issues, weakness in the legs, awkward gait, facial palsy, bladder problems, vertigo, and back pain. In rare cases, untreated Lyme disease may cause frank psychosis, which has been misdiagnosed as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Panic attacks and anxiety can occur; also, delusional behavior may be seen, including somatoform delusions, sometimes accompanied by a depersonalization or derealization syndrome, where the people begin to feel detached from themselves or from reality.[44][45]

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA) is a chronic skin disorder observed primarily in Europe among the elderly.[38] ACA begins as a reddish-blue patch of discolored skin, often on the backs of the hands or feet. The lesion slowly atrophies over several weeks or months, with the skin becoming first thin and wrinkled and then, if untreated, completely dry and hairless.[46]

Cause

Lyme disease is caused by spirochetes, spiral bacteria from the genus Borrelia. Spirochetes are surrounded by peptidoglycan and flagella, along with an outer membrane similar to Gram-negative bacteria. Because of their double-membrane envelope, Borrelia bacteria are often mistakenly described as Gram negative despite the considerable differences in their envelope components from Gram-negative bacteria.[47] The Lyme-related Borrelia species are collectively known as Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, and show a great deal of genetic diversity.

B. burgdorferi sensu lato is made up of 21 closely related species, but only four clearly cause Lyme disease: B. mayonii (found in North America), B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (predominant in North America, but also present in Europe), B. afzelii, and B. garinii (both predominant in Eurasia).[48][49][10] Some studies have also proposed that B. bissettii and B. valaisiana may sometimes infect humans, but these species do not seem to be important causes of disease.[50][51]

Transmission

Lyme disease is classified as a zoonosis, as it is transmitted to humans from a natural reservoir among small mammals and birds by ticks that feed on both sets of hosts.[52] Hard-bodied ticks of the genus Ixodes are the main vectors of Lyme disease (also the vector for Babesia).[53] Most infections are caused by ticks in the nymphal stage, because they are very small and thus may feed for long periods of time undetected.[52] Nymphal ticks are generally the size of a poppy seed and sometimes with a dark head and a translucent body.[54] Or, the nymphal ticks can be darker.[55] (The younger larval ticks are very rarely infected.[56]) Although deer are the preferred hosts of adult deer ticks, and tick populations are much lower in the absence of deer, ticks generally do not acquire Borrelia from deer, instead they obtain them from infected small mammals such as the white-footed mouse, and occasionally birds.[57] Areas where Lyme is common are expanding.[58]

Within the tick midgut, the Borrelia's outer surface protein A (OspA) binds to the tick receptor for OspA, known as TROSPA. When the tick feeds, the Borrelia downregulates OspA and upregulates OspC, another surface protein. After the bacteria migrate from the midgut to the salivary glands, OspC binds to Salp15, a tick salivary protein that appears to have immunosuppressive effects that enhance infection.[59] Successful infection of the mammalian host depends on bacterial expression of OspC.[60]

Tick bites often go unnoticed because of the small size of the tick in its nymphal stage, as well as tick secretions that prevent the host from feeling any itch or pain from the bite. However, transmission is quite rare, with only about 1.2 to 1.4 percent of recognized tick bites resulting in Lyme disease.[61]

In Europe, the vector is Ixodes ricinus, which is also called the sheep tick or castor bean tick.[62] In China, Ixodes persulcatus (the taiga tick) is probably the most important vector.[63] In North America, the black-legged tick or deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) is the main vector on the East Coast.[56]

The lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum), which is found throughout the Southeastern United States as far west as Texas, is unlikely to transmit the Lyme disease spirochetes,[64] though it may be implicated in a related syndrome called southern tick-associated rash illness, which resembles a mild form of Lyme disease.[65]

On the West Coast of the United States, the main vector is the western black-legged tick (Ixodes pacificus).[66] The tendency of this tick species to feed predominantly on host species such as lizards that are resistant to Borrelia infection appears to diminish transmission of Lyme disease in the West.[67][68]

Transmission can occur across the placenta during pregnancy and as with a number of other spirochetal diseases, adverse pregnancy outcomes are possible with untreated infection; prompt treatment with antibiotics reduces or eliminates this risk.[69][70][71][72][73]

While Lyme spirochetes have been found in insects, as well as ticks,[74] reports of actual infectious transmission appear to be rare.[75] Lyme spirochete DNA has been found in semen[76] and breast milk.[77] However, according to the CDC, live spirochetes have not been found in breast milk, urine, or semen and thus is not sexually transmitted.[78]

Tick-borne coinfections

Ticks that transmit B. burgdorferi to humans can also carry and transmit several other parasites, such as Theileria microti and Anaplasma phagocytophilum, which cause the diseases babesiosis and human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA), respectively.[79] Among people with early Lyme disease, depending on their location, 2–12% will also have HGA and 2–40% will have babesiosis.[80] Ticks in certain regions, including the lands along the eastern Baltic Sea, also transmit tick-borne encephalitis.[81]

Coinfections complicate Lyme symptoms, especially diagnosis and treatment. It is possible for a tick to carry and transmit one of the coinfections and not Borrelia, making diagnosis difficult and often elusive. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention studied 100 ticks in rural New Jersey, and found 55% of the ticks were infected with at least one of the pathogens.[82]

Pathophysiology

B. burgdorferi can spread throughout the body during the course of the disease, and has been found in the skin, heart, joints, peripheral nervous system, and central nervous system.[60][83] Many of the signs and symptoms of Lyme disease are a consequence of the immune response to spirochete in those tissues.[40]

B. burgdorferi is injected into the skin by the bite of an infected Ixodes tick. Tick saliva, which accompanies the spirochete into the skin during the feeding process, contains substances that disrupt the immune response at the site of the bite.[84] This provides a protective environment where the spirochete can establish infection. The spirochetes multiply and migrate outward within the dermis. The host inflammatory response to the bacteria in the skin causes the characteristic circular EM lesion.[60] Neutrophils, however, which are necessary to eliminate the spirochetes from the skin, fail to appear in necessary numbers in the developing EM lesion, mostly due to the fact that tick saliva also inhibits neutrophil function. This allows the bacteria to survive and eventually spread throughout the body.[85]

Days to weeks following the tick bite, the spirochetes spread via the bloodstream to joints, heart, nervous system, and distant skin sites, where their presence gives rise to the variety of symptoms of the disseminated disease. The spread of B. burgdorferi is aided by the attachment of the host protease plasmin to the surface of the spirochete.[86]

If untreated, the bacteria may persist in the body for months or even years, despite the production of B. burgdorferi antibodies by the immune system.[87] The spirochetes may avoid the immune response by decreasing expression of surface proteins that are targeted by antibodies, antigenic variation of the VlsE surface protein, inactivating key immune components such as complement, and hiding in the extracellular matrix, which may interfere with the function of immune factors.[88][89]

In the brain, B. burgdorferi may induce astrocytes to undergo astrogliosis (proliferation followed by apoptosis), which may contribute to neurodysfunction.[90] The spirochetes may also induce host cells to secrete quinolinic acid, which stimulates the NMDA receptor on nerve cells, which may account for the fatigue and malaise observed with Lyme encephalopathy.[91] In addition, diffuse white matter pathology during Lyme encephalopathy may disrupt gray matter connections, and could account for deficits in attention, memory, visuospatial ability, complex cognition, and emotional status. White matter disease may have a greater potential for recovery than gray matter disease, perhaps because the neuronal loss is less common. Resolution of MRI white matter hyperintensities after antibiotic treatment has been observed.[92]

Tryptophan, a precursor to serotonin, appears to be reduced within the central nervous system in a number of infectious diseases that affect the brain, including Lyme.[93] Researchers are investigating if this neurohormone secretion is the cause of neuropsychiatric disorders developing in some people with borreliosis.[94]

Immunological studies

Exposure to the Borrelia bacterium during Lyme disease possibly causes a long-lived and damaging inflammatory response,[95] a form of pathogen-induced autoimmune disease.[96] The production of this reaction might be due to a form of molecular mimicry, where Borrelia avoids being killed by the immune system by resembling normal parts of the body's tissues.[97][98]

Chronic symptoms from an autoimmune reaction could explain why some symptoms persist even after the spirochetes have been eliminated from the body. This hypothesis may explain why chronic arthritis persists after antibiotic therapy, similar to rheumatic fever, but its wider application is controversial.[99][100]

Diagnosis

Lyme disease is diagnosed based on symptoms, objective physical findings (such as erythema migrans (EM) rash, facial palsy, or arthritis), history of possible exposure to infected ticks, and possibly laboratory tests.[2][22] People with symptoms of early Lyme disease should have a total body skin examination for EM rashes and asked whether EM-type rashes had manifested within the last 1-2 months.[29] Presence of an EM rash and recent tick exposure (i.e., being outdoors in a likely tick habitat where Lyme is common, within 30 days of the appearance of the rash) are sufficient for Lyme diagnosis; no laboratory confirmation is needed or recommended.[2][22][101][102] Most people who get infected do not remember a tick or a bite, and the EM rash need not look like a bull's eye (most EM rashes in the U.S. do not) or be accompanied by any other symptoms.[2][103] In the U.S., Lyme is most common in the New England and Mid-Atlantic states and parts of Wisconsin and Minnesota, but it is expanding into other areas.[58] Several bordering areas of Canada also have high Lyme risk.[104]

In the absence of an EM rash or history of tick exposure, Lyme diagnosis depends on laboratory confirmation.[53][105] The bacteria that cause Lyme disease are difficult to observe directly in body tissues and also difficult and too time-consuming to grow in the laboratory.[2][53] The most widely used tests look instead for presence of antibodies against those bacteria in the blood.[106] A positive antibody test result does not by itself prove active infection, but can confirm an infection that is suspected because of symptoms, objective findings, and history of tick exposure in a person.[53] Because as many as 5-20% of the normal population have antibodies against Lyme, people without history and symptoms suggestive of Lyme disease should not be tested for Lyme antibodies: a positive result would likely be false, possibly causing unnecessary treatment.[29][31]

In some cases, when history, signs, and symptoms are strongly suggestive of early disseminated Lyme disease, empiric treatment may be started and reevaluated as laboratory test results become available.[34][107]

Laboratory testing

Tests for antibodies in the blood by ELISA and Western blot is the most widely used method for Lyme diagnosis. A two-tiered protocol is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): the sensitive ELISA test is performed first, and if it is positive or equivocal, then the more specific Western blot is run.[108] The immune system takes some time to produce antibodies in quantity. After Lyme infection onset, antibodies of types IgM and IgG usually can first be detected respectively at 2–4 weeks and 4–6 weeks, and peak at 6–8 weeks.[109] When an EM rash first appears, detectable antibodies may not be present. Therefore, it is recommended that testing not be performed and diagnosis be based on the presence of the EM rash.[29] Up to 30 days after suspected Lyme infection onset, infection can be confirmed by detection of IgM or IgG antibodies; after that, it is recommended that only IgG antibodies be considered.[109] A positive IgM and negative IgG test result after the first month of infection is generally indicative of a false positive result.[110] The number of IgM antibodies usually collapses 4–6 months after infection, while IgG antibodies can remain detectable for years.[109]

Other tests may be used in neuroborreliosis cases. In Europe, neuroborreliosis is usually caused by Borrelia garinii and almost always involves lymphocytic pleocytosis, i.e. the densities of lymphocytes (infection-fighting cells) and protein in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) typically rise to characteristically abnormal levels, while glucose level remains normal.[32][29][33] Additionally, the immune system produces antibodies against Lyme inside the intrathecal space, which contains the CSF.[29][33] Demonstration by lumbar puncture and CSF analysis of pleocytosis and intrathecal antibody production are required for definite diagnosis of neuroborreliosis in Europe (except in cases of peripheral neuropathy associated with acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, which usually is caused by Borrelia afzelii and confirmed by blood antibody tests).[31] In North America, neuroborreliosis is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and may not be accompanied by the same CSF signs; they confirm a diagnosis of central nervous system (CNS) neuroborreliosis if positive, but do not exclude it if negative.[111] American guidelines consider CSF analysis optional when symptoms appear to be confined to the peripheral nervous system (PNS), e.g. facial palsy without overt meninigitis symptoms.[29][112] Unlike blood and intrathecal antibody tests, CSF pleocytosis tests revert to normal after infection ends and therefore can be used as objective markers of treatment success and inform decisions on whether to retreat.[33] In infection involving the PNS, electromyography and nerve conduction studies can be used to monitor objectively the response to treatment.[32]

In Lyme carditis, electrocardiograms are used to evidence heart conduction abnormalities, while echocardiography may show myocardial dysfunction.[36] Biopsy and confirmation of Borrelia cells in myocardial tissue may be used in specific cases but are usually not done because of risk of the procedure.[36]

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for Lyme disease have also been developed to detect the genetic material (DNA) of the Lyme disease spirochete. Culture or PCR are the current means for detecting the presence of the organism, as serologic studies only test for antibodies of Borrelia. PCR has the advantage of being much faster than culture. However, PCR tests are susceptible to false positive results, e.g. by detection of debris of dead Borrelia cells or specimen contamination.[113][31] Even when properly performed, PCR often shows false negative results because few Borrelia cells can be found in blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) during infection.[114][31] Hence, PCR tests are recommended only in special cases, e.g. diagnosis of Lyme arthritis, because it is a highly sensitive way of detecting ospA DNA in synovial fluid.[115] Although sensitivity of PCR in CSF is low, its use may be considered when intrathecal antibody production test results are suspected of being falsely negative, e.g. in very early (< 6 weeks) neuroborreliosis or in immunosuppressed people.[31]

Several other forms of laboratory testing for Lyme disease are available, some of which have not been adequately validated. OspA antigens, shed by live Borrelia bacteria into urine, are a promising technique being studied.[116] The use of nanotrap particles for their detection is being looked at and the OspA has been linked to active symptoms of Lyme.[117][118] High titers of either immunoglobulin G (IgG) or immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies to Borrelia antigens indicate disease, but lower titers can be misleading, because the IgM antibodies may remain after the initial infection, and IgG antibodies may remain for years.[119]

The CDC does not recommend urine antigen tests, PCR tests on urine, immunofluorescent staining for cell-wall-deficient forms of B. burgdorferi, and lymphocyte transformation tests.[114]

Imaging

Neuroimaging is controversial in whether it provides specific patterns unique to neuroborreliosis, but may aid in differential diagnosis and in understanding the pathophysiology of the disease.[120] Though controversial, some evidence shows certain neuroimaging tests can provide data that are helpful in the diagnosis of a person. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) are two of the tests that can identify abnormalities in the brain of a person affected with this disease. Neuroimaging findings in an MRI include lesions in the periventricular white matter, as well as enlarged ventricles and cortical atrophy. The findings are considered somewhat unexceptional because the lesions have been found to be reversible following antibiotic treatment. Images produced using SPECT show numerous areas where an insufficient amount of blood is being delivered to the cortex and subcortical white matter. However, SPECT images are known to be nonspecific because they show a heterogeneous pattern in the imaging. The abnormalities seen in the SPECT images are very similar to those seen in people with cerebral vacuities and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, which makes them questionable.[121]

Differential diagnosis

Community clinics have been reported to misdiagnose 23–28% of Erythema migrans (EM) rashes and 83% of other objective manifestations of early Lyme disease.[105] EM rashes are often misdiagnosed as spider bites, cellulitis, or shingles.[105] Many misdiagnoses are credited to the widespread misconception that EM rashes should look like a bull's eye.[2] Actually, the key distinguishing features of the EM rash are the speed and extent to which it expands, respectively up to 2–3 cm/day and a diameter of at least 5 cm, and in 50% of cases more than 16 cm. The rash expands away from its center, which may or may not look different or be separated by ring-like clearing from the rest of the rash.[22][23] Compared to EM rashes, spider bites are more common in the limbs, tend to be more painful and itchy or become swollen, and some may cause necrosis (sinking dark blue patch of dead skin).[22][2] Cellulitis most commonly develops around a wound or ulcer, is rarely circular, and is more likely to become swollen and tender.[22][2] EM rashes often appear at sites that are unusual for cellulitis, such as the armpit, groin, abdomen, or back of knee.[22] Like Lyme, shingles often begins with headache, fever, and fatigue, which are followed by pain or numbness. However, unlike Lyme, in shingles these symptoms are usually followed by appearance of rashes composed of multiple small blisters along a nerve's dermatome, and shingles can also be confirmed by quick laboratory tests.[122]

Facial palsy caused by Lyme disease (LDFP) is often misdiagnosed as Bell's palsy.[34] Although Bell's palsy is the most common type of one-sided facial palsy (about 70% of cases), LDFP can account for about 25% of cases of facial palsy in areas where Lyme disease is common.[34] Compared to LDFP, Bell's palsy much less frequently affects both sides of the face.[34] Even though LDFP and Bell's palsy have similar symptoms and evolve similarly if untreated, corticosteroid treatment is beneficial for Bell's Palsy, while being detrimental for LDFP.[34] Recent history of exposure to a likely tick habitat during warmer months, EM rash, viral-like symptoms such as headache and fever, and/or palsy in both sides of the face should be evaluated for likelihood of LDFP; if it is more than minimal, empiric therapy with antibiotics should be initiated, without corticosteroids, and reevaluated upon completion of laboratory tests for Lyme disease.[34]

Unlike viral meningitis, Lyme lymphocytic meningitis tends to not cause fever, last longer, and recur.[32][29] Lymphocytic meningitis is also characterized by possibly co-occurring with EM rash, facial palsy, or partial vision obstruction and having much lower percentage of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in CSF.[29]

Lyme radiculopathy affecting the limbs is often misdiagnosed as a radiculopathy caused by nerve root compression, such as sciatica.[105][123] Although most cases of radiculopathy are compressive and resolve with conservative treatment (e.g., rest) within 4–6 weeks, guidelines for managing radiculopathy recommend first evaluating risks of other possible causes that, although less frequent, require immediate diagnosis and treatment, including infections such as Lyme and shingles.[124] A history of outdoor activities in likely tick habitats in the last 3 months possibly followed by a rash or viral-like symptoms, and current headache, other symptoms of lymphocytic meningitis, or facial palsy would lead to suspicion of Lyme disease and recommendation of serological and lumbar puncture tests for confirmation.[124]

Lyme radiculopathy affecting the trunk can be misdiagnosed as myriad other conditions, such as diverticulitis and acute coronary syndrome.[35][105] Diagnosis of late-stage Lyme disease is often complicated by a multifaceted appearance and nonspecific symptoms, prompting one reviewer to call Lyme the new "great imitator".[125] Lyme disease may be misdiagnosed as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, lupus, Crohn's disease, HIV, or other autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases. As all people with later-stage infection will have a positive antibody test, simple blood tests can exclude Lyme disease as a possible cause of a person's symptoms.[126]

Prevention

Tick bites may be prevented by avoiding or reducing time in likely tick habitats and taking precautions while in and when getting out of one.[127]

Most Lyme human infections are caused by Ixodes nymph bites between April and September.[22][127] Ticks prefer moist, shaded locations in woodlands, shrubs, tall grasses and leaf litter or wood piles.[22][128] Tick densities tend to be highest in woodlands, followed by unmaintained edges between woods and lawns (about half as high), ornamental plants and perennial groundcover (about a quarter), and lawns (about 30 times less).[129] Ixodes larvae and nymphs tend to be abundant also where mice nest, such as stone walls and wood logs.[129] Ixodes larvae and nymphs typically wait for potential hosts ("quest") on leaves or grasses close to the ground with forelegs outstretched; when a host brushes against its limbs, the tick rapidly clings and climbs on the host looking for a skin location to bite.[130] In Northeastern United States, 69% of tick bites are estimated to happen in residences, 11% in schools or camps, 9% in parks or recreational areas, 4% at work, 3% while hunting, and 4% in other areas.[129] Activities associated with tick bites around residences include yard work, brush clearing, gardening, playing in the yard, and letting into the house dogs or cats that roam outside in woody or grassy areas.[129][127] In parks, tick bites often happen while hiking or camping.[129] Walking on a mowed lawn or center of a trail without touching adjacent vegetation is less risky than crawling or sitting on a log or stone wall.[129][131] Pets should not be allowed to roam freely in likely tick habitats.[128]

As a precaution, CDC recommends soaking or spraying clothes, shoes, and camping gear such as tents, backpacks and sleeping bags with 0.5% permethrin solution and hanging them to dry before use.[127][132] Permethrin is odorless and safe for humans but highly toxic to ticks.[133] After crawling on permethrin-treated fabric for as few as 10–20 seconds, tick nymphs become irritated and fall off or die.[133][134] Permethrin-treated closed-toed shoes and socks reduce by 74 times the number of bites from nymphs that make first contact with a shoe of a person also wearing treated shorts (because nymphs usually quest near the ground, this is a typical contact scenario).[133] Better protection can be achieved by tucking permethrin-treated trousers (pants) into treated socks and a treated long-sleeve shirt into the trousers so as to minimize gaps through which a tick might reach the wearer's skin.[131] Light-colored clothing may make it easier to see ticks and remove them before they bite.[131] Military and outdoor workers' uniforms treated with permethrin have been found to reduce the number of bite cases by 80-95%.[134] Permethrin protection lasts several weeks of wear and washings in customer-treated items and up to 70 washings for factory-treated items.[132] Permethrin should not be used on human skin, underwear or cats.[132][135]

The EPA recommends several tick repellents for use on exposed skin, including DEET, picaridin, IR3535 (a derivative of amino acid beta-alanine), oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE, a natural compound) and OLE's active ingredient para-menthane-diol (PMD).[127][136][137] Unlike permethrin, repellents repel but do not kill ticks, protect for only several hours after application, and may be washed off by sweat or water.[132] The most popular repellent is DEET in the U.S. and picaridin in Europe.[137] Unlike DEET, picaridin is odorless and is less likely to irritate the skin or harm fabric or plastics.[137] Repellents with higher concentration may last longer but are not more effective; against ticks, 20% picaridin may work for 8 hours vs. 55–98.11% DEET for 5–6 hours or 30-40% OLE for 6 hours.[132][136] Repellents should not be used under clothes, on eyes, mouth, wounds or cuts, or on babies younger than 2 months (3 years for OLE or PMD).[132][127] If sunscreen is used, repellent should be applied on top of it.[132] Repellents should not be sprayed directly on a face, but should instead be sprayed on a hand and then rubbed on the face.[132]

After coming indoors, clothes, gear and pets should be checked for ticks.[127] Clothes can be put into a hot dryer for 10 minutes to kill ticks (just washing or warm dryer are not enough).[127] Showering as soon as possible, looking for ticks over the entire body, and removing them reduce risk of infection.[127] Unfed tick nymphs are the size of a poppy seed, but a day or two after biting and attaching themselves to a person, they look like a small blood blister.[138] The following areas should be checked especially carefully: armpits, between legs, back of knee, bellybutton, trunk, and in children ears, neck and hair.[127]

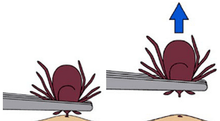

Tick removal

Attached ticks should be removed promptly. Risk of infection increases with time of attachment, but in North America risk of Lyme disease is small if the tick is removed within 36 hours.[139] CDC recommends inserting a fine-tipped tweezer between the skin and the tick, grasping very firmly, and pulling the closed tweezer straight away from the skin without twisting, jerking, squeezing or crushing the tick.[140] After tick removal, any tick parts remaining in the skin should be removed with the tweezer, if possible.[140] Wound and hands should then be cleaned with alcohol or soap and water.[140] The tick may be disposed by placing it in a container with alcohol, sealed bag, tape or flushed down the toilet.[140] The bitten person should write down where and when the bite happened so that this can be informed to a doctor if the person gets a rash or flu-like symptoms in the following several weeks.[140] CDC recommends not using fingers, nail polish, petroleum jelly or heat on the tick to try to remove it.[140]

In Australia, where the Australian paralysis tick is prevalent, the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy recommends not using tweezers to remove ticks, because if the person is allergic, anaphylaxis could result.[141] Instead, a product should be sprayed on the tick to cause it to freeze and then drop off.[141] A doctor would use liquid nitrogen, but products available from chemists for freezing warts can be used instead.[142] Another method originating from Australia consists in using about 20 cm of dental floss or fishing line for slowly tying an overhand knot between the skin and the tick and then pulling it away from the skin.[143][144]

Preventive antibiotics

The risk of infectious transmission increases with the duration of tick attachment.[22] It requires between 36 and 48 hours of attachment for the bacteria that causes Lyme to travel from within the tick into its saliva.[22] If a deer tick that is sufficiently likely to be carrying Borrelia is found attached to a person and removed, and if the tick has been attached for 36 hours or is engorged, a single dose of doxycycline administered within the 72 hours after removal may reduce the risk of Lyme disease. It is not generally recommended for all people bitten, as development of infection is rare: about 50 bitten people would have to be treated this way to prevent one case of erythema migrans (i.e. the typical rash found in about 70–80% of people infected).[2][22]

Garden landscaping

Several landscaping practices may reduce risk of tick bites in residential yards.[138][145] The lawn should be kept mowed, leaf litter and weeds removed and groundcover use avoided.[138] Woodlands, shrubs, stone walls and wood piles should be separated from the lawn by a 3-ft-wide rock or woodchip barrier.[145] Without vegetation on the barrier, ticks will tend not to cross it; acaricides may also be sprayed on it to kill ticks.[145] A sun-exposed tick-safe zone at least 9 ft from the barrier should concentrate human activity on the yard, including any patios, playgrounds and gardening.[145] Materials such as wood decking, concrete, bricks, gravel or woodchips may be used on the ground under patios and playgrounds so as to discourage ticks there.[138] An 8-ft-high fence may be added to keep deer away from the tick-safe zone.[145][138]

Occupational exposure

Outdoor workers are at risk of Lyme disease if they work at sites with infected ticks. This includes construction, landscaping, forestry, brush clearing, land surveying, farming, railroad work, oil field work, utility line work, park or wildlife management.[146][147] U.S. workers in the northeastern and north-central states are at highest risk of exposure to infected ticks. Ticks may also transmit other tick-borne diseases to workers in these and other regions of the country. Worksites with woods, bushes, high grass or leaf litter are likely to have more ticks. Outdoor workers should be most careful to protect themselves in the late spring and summer when young ticks are most active.[148]

Host animals

Lyme and other deer tick-borne diseases can sometimes be reduced by greatly reducing the deer population on which the adult ticks depend for feeding and reproduction. Lyme disease cases fell following deer eradication on an island, Monhegan, Maine,[149] and following deer control in Mumford Cove, Connecticut.[150] It is worth noting that eliminating deer may lead to a temporary increase in tick density.[151]

For example, in the U.S., reducing the deer population to levels of 8 to 10 per square mile (from the current levels of 60 or more deer per square mile in the areas of the country with the highest Lyme disease rates) may reduce tick numbers and reduce the spread of Lyme and other tick-borne diseases.[152] However, such a drastic reduction may be very difficult to implement in many areas, and low to moderate densities of deer or other large mammal hosts may continue to feed sufficient adult ticks to maintain larval densities at high levels. Routine veterinary control of ticks of domestic animals, including livestock, by use of acaricides can contribute to reducing exposure of humans to ticks.

In Europe, known reservoirs of Borrelia burgdorferi were 9 small mammals, 7 medium-sized mammals and 16 species of birds (including passerines, sea-birds and pheasants).[153] These animals seem to transmit spirochetes to ticks and thus participate in the natural circulation of B. burgdorferi in Europe. The house mouse is also suspected as well as other species of small rodents, particularly in Eastern Europe and Russia.[153] "The reservoir species that contain the most pathogens are the European roe deer Capreolus capreolus;[154] "it does not appear to serve as a major reservoir of B. burgdorferi" thought Jaenson & al. (1992)[155] (incompetent host for B. burgdorferi and TBE virus) but it is important for feeding the ticks,[156] as red deer and wild boars (Sus scrofa),[157] in which one Rickettsia and three Borrelia species were identified",[154] with high risks of coinfection in roe deer.[158] Nevertheless, in the 2000s, in roe deer in Europe "two species of Rickettsia and two species of Borrelia were identified".[157]

Vaccination

A recombinant vaccine against Lyme disease, based on the outer surface protein A (ospA) of B. burgdorferi, was developed by SmithKline Beecham. In clinical trials involving more than 10,000 people, the vaccine, called LYMErix, was found to confer protective immunity to Borrelia in 76% of adults and 100% of children with only mild or moderate and transient adverse effects.[159] LYMErix was approved on the basis of these trials by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 21 December 1998.

Following approval of the vaccine, its entry in clinical practice was slow for a variety of reasons, including its cost, which was often not reimbursed by insurance companies.[160] Subsequently, hundreds of vaccine recipients reported they had developed autoimmune and other side effects. Supported by some advocacy groups, a number of class-action lawsuits were filed against GlaxoSmithKline, alleging the vaccine had caused these health problems. These claims were investigated by the FDA and the Centers for Disease Control, which found no connection between the vaccine and the autoimmune complaints.[161]

Despite the lack of evidence that the complaints were caused by the vaccine, sales plummeted and LYMErix was withdrawn from the U.S. market by GlaxoSmithKline in February 2002,[162] in the setting of negative media coverage and fears of vaccine side effects.[161][163] The fate of LYMErix was described in the medical literature as a "cautionary tale";[163] an editorial in Nature cited the withdrawal of LYMErix as an instance in which "unfounded public fears place pressures on vaccine developers that go beyond reasonable safety considerations."[20] The original developer of the OspA vaccine at the Max Planck Institute told Nature: "This just shows how irrational the world can be ... There was no scientific justification for the first OspA vaccine LYMErix being pulled."[161]

Vaccines have been formulated and approved for prevention of Lyme disease in dogs. Currently, three Lyme disease vaccines are available. LymeVax, formulated by Fort Dodge Laboratories, contains intact dead spirochetes which expose the host to the organism. Galaxy Lyme, Intervet-Schering-Plough's vaccine, targets proteins OspC and OspA. The OspC antibodies kill any of the bacteria that have not been killed by the OspA antibodies. Canine Recombinant Lyme, formulated by Merial, generates antibodies against the OspA protein so a tick feeding on a vaccinated dog draws in blood full of anti-OspA antibodies, which kill the spirochetes in the tick's gut before they are transmitted to the dog.[164]

A hexavalent (OspA) protein subunit-based vaccine candidate VLA15 was granted fast track designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2017 which will allow further study.[165]

Treatment

Antibiotics are the primary treatment.[2][22] The specific approach to their use is dependent on the individual affected and the stage of the disease.[22] For most people with early localized infection, oral administration of doxycycline is widely recommended as the first choice, as it is effective against not only Borrelia bacteria but also a variety of other illnesses carried by ticks.[22] People taking doxycycline should avoid sun exposure because of higher risk of sunburns.[29] Doxycycline is contraindicated in children younger than eight years of age and women who are pregnant or breastfeeding;[22] alternatives to doxycycline are amoxicillin, cefuroxime axetil, and azithromycin.[22] Azithromicyn is recommended only in case of intolerance to the other antibiotics.[29] The standard treatment for cellulitis, cephalexin, is not useful for Lyme disease.[29] When it is unclear if a rash is caused by Lyme or cellulitis, the IDSA recommends treatment with cefuroxime or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, as these are effective against both infections.[29] Individuals with early disseminated or late Lyme infection may have symptomatic cardiac disease, Lyme arthritis, or neurologic symptoms like facial palsy, radiculopathy, meningitis, or peripheral neuropathy.[22] Intravenous administration of ceftriaxone is recommended as the first choice in these cases;[22] cefotaxime and doxycycline are available as alternatives.[22]

These treatment regimens last from one to four weeks.[22] Neurologic complications of Lyme disease may be treated with doxycycline as it can be taken by mouth and has a lower cost, although in North America evidence of efficacy is only indirect.[112] In case of failure, guidelines recommend retreatment with injectable ceftriaxone.[112] Several months after treatment for Lyme arthritis, if joint swelling persists or returns, a second round of antibiotics may be considered; intravenous antibiotics are preferred for retreatment in case of poor response to oral antibiotics.[22][29] Outside of that, a prolonged antibiotic regimen lasting more than 28 days is not recommended as no evidence shows it to be effective.[22][166] IgM and IgG antibody levels may be elevated for years even after successful treatment with antibiotics.[22] As antibody levels are not indicative of treatment success, testing for them is not recommended.[22]

Facial palsy may resolve without treatment; however, antibiotic treatment is recommended to stop other Lyme complications.[29] Corticosteroids are not recommended when facial palsy is caused by Lyme disease.[34] In those with facial palsy, frequent use of artificial tears while awake is recommended, along with ointment and a patch or taping the eye closed when sleeping.[34][167]

About a third of people with Lyme carditis need a temporary pacemaker until their heart conduction abnormality resolves, and 21% need to be hospitalized.[36] Lyme carditis should not be treated with corticosteroids.[36]

People with Lyme arthritis should limit their level of physical activity to avoid damaging affected joints, and in case of limping should use crutches.[168] Pain associated with Lyme disease may be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[29] Corticosteroid joint injections are not recommended for Lyme arthritis that is being treated with antibiotics.[29][168] People with Lyme arthritis treated with intravenous antibiotics or two months of oral antibiotics who continue to have joint swelling two months after treatment and have negative PCR test for Borrelia DNA in the synovial fluid are said to have antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis; this is more common after infection by certain Borrelia strains in people with certain genetic and immunologic characteristics.[29][168] Antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis may be symptomatically treated with NSAIDs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), or arthroscopic synovectomy.[29] Physical therapy is recommended for adults after resolution of Lyme arthritis.[168]

People receiving treatment should be advised that reinfection is possible and how to prevent it.[107]

Prognosis

Lyme disease's typical first sign, the erythema migrans (EM) rash, resolves within several weeks even without treatment.[2] However, in untreated people, the infection often disseminates to the nervous system, heart, or joints, possibly causing permanent damage to body tissues.[29]

People who receive recommended antibiotic treatment within several days of appearance of an initial EM rash have the best prospects.[105] Recovery may not be total or immediate. The percentage of people achieving full recovery in the United States increases from about 64–71% at end of treatment for EM rash to about 84–90% after 30 months; higher percentages are reported in Europe.[169][170] Treatment failure, i.e. persistence of original or appearance of new signs of the disease, occurs only in a few people.[169] Remaining people are considered cured but continue to experience subjective symptoms, e.g. joint or muscle pains or fatigue.[171] These symptoms usually are mild and nondisabling.[171]

People treated only after nervous system manifestations of the disease may end up with objective neurological deficits, in addition to subjective symptoms.[29] In Europe, an average of 32–33 months after initial Lyme symptoms in people treated mostly with doxycycline 200 mg for 14–21 days, the percentage of people with lingering symptoms was much higher among those diagnosed with neuroborreliosis (50%) than among those with only an EM rash (16%).[172] In another European study, 5 years after treatment for neuroborreliosis, lingering symptoms were less common among children (15%) than adults (30%), and in the latter was less common among those treated within 30 days of the first symptom (16%) than among those treated later (39%); among those with lingering symptoms, 54% had daily activities restricted and 19% were on sick leave or incapacitated.[173]

Some data suggest that about 90% of Lyme facial palsies treated with antibiotics recover fully a median of 24 days after appearing and most of the rest recover with only mild abnormality.[174][175] However, in Europe 41% of people treated for facial palsy had other lingering symptoms at followup up to 6 months later, including 28% with numbness or altered sensation and 14% with fatigue or concentration problems.[175] Palsies in both sides of the face are associated with worse and longer time to recovery.[174][175] Historical data suggests that untreated people with facial palsies recover at nearly the same rate, but 88% subsequently have Lyme arthritis.[174][176] Other research shows that synkinesis (involuntary movement of a facial muscle when another one is voluntarily moved) can become evident only 6–12 months after facial palsy appears to be resolved, as damaged nerves regrow and sometimes connect to incorrect muscles.[177] Synkinesis is associated with corticosteroid use.[177] In longer-term follow-up, 16–23% of Lyme facial palsies do not fully recover.[177]

In Europe, about a quarter of people with Bannwarth syndrome (Lyme radiculopathy and lymphocytic meningitis) treated with intravenous ceftriaxone for 14 days an average of 30 days after first symptoms had to be retreated 3–6 months later because of unsatisfactory clinical response or continued objective markers of infection in cerebrospinal fluid; after 12 months, 64% recovered fully, 31% had nondisabling mild or infrequent symptoms that did not require regular use of analgesics, and 5% had symptoms that were disabling or required substantial use of analgesics.[33] The most common lingering nondisabling symptoms were headache, fatigue, altered sensation, joint pains, memory disturbances, malaise, radicular pain, sleep disturbances, muscle pains, and concentration disturbances. Lingering disabling symptoms included facial palsy and other impaired movement.[33]

Recovery from late neuroborreliosis tends to take longer and be less complete than from early neuroborreliosis, probably because of irreversible neurologic damage.[29]

About half the people with Lyme carditis progress to complete heart block, but it usually resolves in a week.[36] Other Lyme heart conduction abnormalities resolve typically within 6 weeks.[36] About 94% of people have full recovery, but 5% need a permanent pacemaker and 1% end up with persistent heart block (the actual percentage may be higher because of unrecognized cases).[36] Lyme myocardial complications usually are mild and self-limiting.[36] However, in some cases Lyme carditis can be fatal.[36]

Recommended antibiotic treatments are effective in about 90% of Lyme arthritis cases, although it can take several months for inflammation to resolve and a second round of antibiotics is often necessary.[29] Antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis also eventually resolves, typically within 9–14 months (range 4 months – 4 years); DMARDs or synovectomy can accelerate recovery.[168]

Reinfection is not uncommon. In a U.S. study, 6–11% of people treated for an EM rash had another EM rash within 30 months.[169] The second rash typically is due to infection by a different Borrelia strain.[178]

People who have nonspecific, subjective symptoms such as fatigue, joint and muscle aches, or cognitive difficulties for more than six months after recommended treatment for Lyme disease are said to have post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. As of 2016 the reason for the lingering symptoms was not known; the condition is generally managed similarly to fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome.[179]

Epidemiology

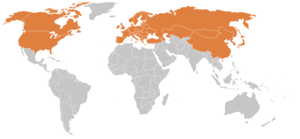

Lyme disease occurs regularly in Northern Hemisphere temperate regions.[180]

Africa

In northern Africa, B. burgdorferi sensu lato has been identified in Morocco, Algeria, Egypt and Tunisia.[181][182][183]

Lyme disease in sub-Saharan Africa is presently unknown, but evidence indicates it may occur in humans in this region. The abundance of hosts and tick vectors would favor the establishment of Lyme infection in Africa.[184] In East Africa, two cases of Lyme disease have been reported in Kenya.[185]

Asia

B. burgdorferi sensu lato-infested ticks are being found more frequently in Japan, as well as in northwest China, Nepal, Thailand and far eastern Russia.[186][187] Borrelia has also been isolated in Mongolia.[188]

Europe

In Europe, Lyme disease is caused by infection with one or more pathogenic European genospecies of the spirochaete B. burgdorferi sensu lato, mainly transmitted by the tick Ixodes ricinus.[189] Cases of B. burgdorferi sensu lato-infected ticks are found predominantly in central Europe, particularly in Slovenia and Austria, but have been isolated in almost every country on the continent.[190] Number of cases in southern Europe, such as Italy and Portugal, is much lower.[191]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom the number of laboratory confirmed cases of Lyme disease has been rising steadily since voluntary reporting was introduced in 1986[192] when 68 cases were recorded in the UK and Republic of Ireland combined.[193] In the UK there were 23 confirmed cases in 1988 and 19 in 1990,[194] but 973 in 2009[192] and 953 in 2010.[195] Provisional figures for the first 3 quarters of 2011 show a 26% increase on the same period in 2010.[196]

It is thought, however, that the actual number of cases is significantly higher than suggested by the above figures, with the UK's Health Protection Agency estimating that there are between 2,000 and 3,000 cases per year,[195] (with an average of around 15% of the infections acquired overseas[192]), while Dr Darrel Ho-Yen, Director of the Scottish Toxoplasma Reference Laboratory and National Lyme Disease Testing Service, believes that the number of confirmed cases should be multiplied by 10 "to take account of wrongly diagnosed cases, tests giving false results, sufferers who weren't tested, people who are infected but not showing symptoms, failures to notify and infected individuals who don't consult a doctor."[197][198]

Despite Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi infection) being a notifiable disease in Scotland[199] since January 1990[200] which should therefore be reported on the basis of clinical suspicion, it is believed that many GPs are unaware of the requirement.[201] Mandatory reporting, limited to laboratory test results only, was introduced throughout the UK in October 2010, under the Health Protection (Notification) Regulations 2010.[192]

Although there is a greater number of cases of Lyme disease in the New Forest, Salisbury Plain, Exmoor, the South Downs, parts of Wiltshire and Berkshire, Thetford Forest[202] and the West coast and islands of Scotland[203] infected ticks are widespread, and can even be found in the parks of London.[194][204] A 1989 report found that 25% of forestry workers in the New Forest were seropositive, as were between 2% and 4–5% of the general local population of the area.[205][206]

Tests on pet dogs, carried out throughout the country in 2009 indicated that around 2.5% of ticks in the UK may be infected, considerably higher than previously thought.[207][208] It is thought that global warming may lead to an increase in tick activity in the future, as well as an increase in the amount of time that people spend in public parks, thus increasing the risk of infection.[209]

North America

Many studies in North America have examined ecological and environmental correlates of the number of people affected by Lyme disease. A 2005 study using climate suitability modelling of I. scapularis projected that climate change would cause an overall 213% increase in suitable vector habitat by the year 2080, with northward expansions in Canada, increased suitability in the central U.S., and decreased suitable habitat and vector retraction in the southern U.S.[210] A 2008 review of published studies concluded that the presence of forests or forested areas was the only variable that consistently elevated the risk of Lyme disease whereas other environmental variables showed little or no concordance between studies.[211] The authors argued that the factors influencing tick density and human risk between sites are still poorly understood, and that future studies should be conducted over longer time periods, become more standardized across regions, and incorporate existing knowledge of regional Lyme disease ecology.[211]

Canada

Owing to changing climate, the range of ticks able to carry Lyme disease has expanded from a limited area of Ontario to include areas of southern Quebec, Manitoba, northern Ontario, southern New Brunswick, southwest Nova Scotia and limited parts of Saskatchewan and Alberta, as well as British Columbia. Cases have been reported as far east as the island of Newfoundland.[104][212][213][214] A model-based prediction by Leighton et al. (2012) suggests that the range of the I. scapularis tick will expand into Canada by 46 km/year over the next decade, with warming climatic temperatures as the main driver of increased speed of spread.[215]

Mexico

A 2007 study suggests Borrelia burgdorferi infections are endemic to Mexico, from four cases reported between 1999 and 2000.[216]

United States

Each year, approximately 30,000 new cases are reported to the CDC however, this number is likely underestimated. The CDC is currently conducting research on evaluation and diagnostics of the disease and preliminary results suggest the number of new cases to be around 300,000.[217][218]

Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne disease in North America and Europe, and one of the fastest-growing infectious diseases in the United States. Of cases reported to the United States CDC, the ratio of Lyme disease infection is 7.9 cases for every 100,000 persons. In the ten states where Lyme disease is most common, the average was 31.6 cases for every 100,000 persons for the year 2005.[219][220][221]

Although Lyme disease has been reported in all states[217][222] about 99% of all reported cases are confined to just five geographic areas (New England, Mid-Atlantic, East-North Central, South Atlantic, and West North-Central).[223] New 2011 CDC Lyme case definition guidelines are used to determine confirmed CDC surveillance cases.[224]

Effective January 2008, the CDC gives equal weight to laboratory evidence from 1) a positive culture for B. burgdorferi; 2) two-tier testing (ELISA screening and Western blot confirming); or 3) single-tier IgG (old infection) Western blot.[225] Previously, the CDC only included laboratory evidence based on (1) and (2) in their surveillance case definition. The case definition now includes the use of Western blot without prior ELISA screen.[225]

The number of reported cases of the disease has been increasing, as are endemic regions in North America. For example, B. burgdorferi sensu lato was previously thought to be hindered in its ability to be maintained in an enzootic cycle in California, because it was assumed the large lizard population would dilute the number of people affected by B. burgdorferi in local tick populations; this has since been brought into question, as some evidence has suggested lizards can become infected.[226]

Except for one study in Europe,[227] much of the data implicating lizards is based on DNA detection of the spirochete and has not demonstrated that lizards are able to infect ticks feeding upon them.[226][228][229][230] As some experiments suggest lizards are refractory to infection with Borrelia, it appears likely their involvement in the enzootic cycle is more complex and species-specific.[68]

While B. burgdorferi is most associated with ticks hosted by white-tailed deer and white-footed mice, Borrelia afzelii is most frequently detected in rodent-feeding vector ticks, and Borrelia garinii and Borrelia valaisiana appear to be associated with birds. Both rodents and birds are competent reservoir hosts for B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. The resistance of a genospecies of Lyme disease spirochetes to the bacteriolytic activities of the alternative complement pathway of various host species may determine its reservoir host association.

Several similar but apparently distinct conditions may exist, caused by various species or subspecies of Borrelia in North America. A regionally restricted condition that may be related to Borrelia infection is southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI), also known as Masters disease. Amblyomma americanum, known commonly as the lone-star tick, is recognized as the primary vector for STARI. In some parts of the geographical distribution of STARI, Lyme disease is quite rare (e.g., Arkansas), so people in these regions experiencing Lyme-like symptoms—especially if they follow a bite from a lone-star tick—should consider STARI as a possibility. It is generally a milder condition than Lyme and typically responds well to antibiotic treatment.[231]

In recent years there have been 5 to 10 cases a year of a disease similar to Lyme occurring in Montana. It occurs primarily in pockets along the Yellowstone River in central Montana. People have developed a red bull's-eye rash around a tick bite followed by weeks of fatigue and a fever.[222]

Lyme disease effects are comparable among males and females. A wide range of age groups is affected, though the number of cases is highest among 10- to 19-year-olds. For unknown reasons, Lyme disease is seven times more common among Asians.[232]

South America

In South America, tick-borne disease recognition and occurrence is rising. In Brazil, a Lyme-like disease known as Baggio–Yoshinari syndrome was identified, caused by microorganisms that do not belong to the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex and transmitted by ticks of the Amblyomma and Rhipicephalus genera.[233] The first reported case of BYS in Brazil was made in 1992 in Cotia, São Paulo.[234] B. burgdorferi sensu stricto antigens in people have been identified in Colombia,[235] and Bolivia.

History

The evolutionary history of Borrelia burgdorferi genetics has been the subject of recent studies. One study has found that prior to the reforestation that accompanied post-colonial farm abandonment in New England and the wholesale migration into the mid-west that occurred during the early 19th century, Lyme disease was present for thousands of years in America and had spread along with its tick hosts from the Northeast to the Midwest.[236]

John Josselyn, who visited New England in 1638 and again from 1663–1670, wrote "there be infinite numbers of tikes hanging upon the bushes in summer time that will cleave to man's garments and creep into his breeches eating themselves in a short time into the very flesh of a man. I have seen the stockins of those that have gone through the woods covered with them."[237]

This is also confirmed by the writings of Peter Kalm, a Swedish botanist who was sent to America by Linnaeus, and who found the forests of New York "abound" with ticks when he visited in 1749. When Kalm's journey was retraced 100 years later, the forests were gone and the Lyme bacterium had probably become isolated to a few pockets along the northeast coast, Wisconsin, and Minnesota.[238]

Perhaps the first detailed description of what is now known as Lyme disease appeared in the writings of John Walker after a visit to the island of Jura (Deer Island) off the west coast of Scotland in 1764.[239] He gives a good description both of the symptoms of Lyme disease (with "exquisite pain [in] the interior parts of the limbs") and of the tick vector itself, which he describes as a "worm" with a body which is "of a reddish colour and of a compressed shape with a row of feet on each side" that "penetrates the skin". Many people from this area of Great Britain emigrated to North America between 1717 and the end of the 18th century.

The examination of preserved museum specimens has found Borrelia DNA in an infected Ixodes ricinus tick from Germany that dates back to 1884, and from an infected mouse from Cape Cod that died in 1894.[238] The 2010 autopsy of Ötzi the Iceman, a 5,300-year-old mummy, revealed the presence of the DNA sequence of Borrelia burgdorferi making him the earliest known human with Lyme disease.[240]

The early European studies of what is now known as Lyme disease described its skin manifestations. The first study dates to 1883 in Breslau, Germany (now Wrocław, Poland), where physician Alfred Buchwald described a man who had suffered for 16 years with a degenerative skin disorder now known as acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans.[241]

At a 1909 research conference, Swedish dermatologist Arvid Afzelius presented a study about an expanding, ring-like lesion he had observed in an older woman following the bite of a sheep tick. He named the lesion erythema migrans.[241] The skin condition now known as borrelial lymphocytoma was first described in 1911.[242]

The modern history of medical understanding of the disease, including its cause, diagnosis, and treatment, has been difficult.[243]

Neurological problems following tick bites were recognized starting in the 1920s. French physicians Garin and Bujadoux described a farmer with a painful sensory radiculitis accompanied by mild meningitis following a tick bite. A large, ring-shaped rash was also noted, although the doctors did not relate it to the meningoradiculitis. In 1930, the Swedish dermatologist Sven Hellerström was the first to propose EM and neurological symptoms following a tick bite were related.[244] In the 1940s, German neurologist Alfred Bannwarth described several cases of chronic lymphocytic meningitis and polyradiculoneuritis, some of which were accompanied by erythematous skin lesions.

Carl Lennhoff, who worked at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, believed many skin conditions were caused by spirochetes. In 1948, he used a special stain to microscopically observe what he believed were spirochetes in various types of skin lesions, including EM.[245] Although his conclusions were later shown to be erroneous, interest in the study of spirochetes was sparked. In 1949, Nils Thyresson, who also worked at the Karolinska Institute, was the first to treat ACA with penicillin.[246] In the 1950s, the relationship among tick bite, lymphocytoma, EM and Bannwarth's syndrome was recognized throughout Europe leading to the widespread use of penicillin for treatment in Europe.[247][248]

In 1970, a dermatologist in Wisconsin named Rudolph Scrimenti recognized an EM lesion in a person after recalling a paper by Hellerström that had been reprinted in an American science journal in 1950. This was the first documented case of EM in the United States. Based on the European literature, he treated the person with penicillin.[249]

The full syndrome now known as Lyme disease was not recognized until a cluster of cases originally thought to be juvenile rheumatoid arthritis was identified in three towns in southeastern Connecticut in 1975, including the towns Lyme and Old Lyme, which gave the disease its popular name.[250] This was investigated by physicians David Snydman and Allen Steere of the Epidemic Intelligence Service, and by others from Yale University, including Stephen Malawista, who is credited as a co-discover of the disease.[251] The recognition that the people in the United States had EM led to the recognition that "Lyme arthritis" was one manifestation of the same tick-borne condition known in Europe.[252]

Before 1976, the elements of B. burgdorferi sensu lato infection were called or known as tick-borne meningopolyneuritis, Garin-Bujadoux syndrome, Bannwarth syndrome, Afzelius's disease,[253] Montauk Knee or sheep tick fever. Since 1976 the disease is most often referred to as Lyme disease,[254][255] Lyme borreliosis or simply borreliosis.[256][257]

In 1980, Steere, et al., began to test antibiotic regimens in adults with Lyme disease.[258] In the same year, New York State Health Dept. epidemiologist Jorge Benach provided Willy Burgdorfer, a researcher at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, with collections of I. dammini [scapularis] from Shelter Island, New York, a known Lyme-endemic area as part of an ongoing investigation of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. In examining the ticks for rickettsiae, Burgdorfer noticed "poorly stained, rather long, irregularly coiled spirochetes." Further examination revealed spirochetes in 60% of the ticks. Burgdorfer credited his familiarity with the European literature for his realization that the spirochetes might be the "long-sought cause of ECM and Lyme disease." Benach supplied him with more ticks from Shelter Island and sera from people diagnosed with Lyme disease. University of Texas Health Science Center researcher Alan Barbour "offered his expertise to culture and immunochemically characterize the organism." Burgdorfer subsequently confirmed his discovery by isolating, from people with Lyme disease, spirochetes identical to those found in ticks.[259] In June 1982, he published his findings in Science, and the spirochete was named Borrelia burgdorferi in his honor.[260]

After the identification of B. burgdorferi as the causative agent of Lyme disease, antibiotics were selected for testing, guided by in vitro antibiotic sensitivities, including tetracycline antibiotics, amoxicillin, cefuroxime axetil, intravenous and intramuscular penicillin and intravenous ceftriaxone.[261][262] The mechanism of tick transmission was also the subject of much discussion. B. burgdorferi spirochetes were identified in tick saliva in 1987, confirming the hypothesis that transmission occurred via tick salivary glands.[263]

Society and culture

Urbanization and other anthropogenic factors can be implicated in the spread of Lyme disease to humans. In many areas, expansion of suburban neighborhoods has led to gradual deforestation of surrounding wooded areas and increased border contact between humans and tick-dense areas. Human expansion has also resulted in a reduction of predators that hunt deer as well as mice, chipmunks and other small rodents—the primary reservoirs for Lyme disease. As a consequence of increased human contact with host and vector, the likelihood of transmission of the disease has greatly increased.[264][265] Researchers are investigating possible links between global warming and the spread of vector-borne diseases, including Lyme disease.[266]

Controversy

The term "chronic Lyme disease" is controversial and not recognized in the medical literature,[267] and most medical authorities advise against long-term antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease.[29][112][268] Studies have shown that most people diagnosed with "chronic Lyme disease" either have no objective evidence of previous or current infection with B. burgdorferi or are people who should be classified as having post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS), which is defined as continuing or relapsing non-specific symptoms (such as fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and cognitive complaints) in a person previously treated for Lyme disease.[269]

Legislation