Karolinska Institute

The Karolinska Institute (KI; Swedish: Karolinska Institutet;[2] sometimes known as the (Royal) Caroline Institute in English[3][4]) is a research-led medical university in Solna within the Stockholm urban area of Sweden. It covers areas such as biochemistry, genetics, pharmacology, pathology, anatomy, physiology and medical microbiology, among others. It is recognised as Sweden's best university and one of the largest, most prestigious medical universities in the world. It is the highest ranked in all Scandinavia. The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute awards the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. The assembly consists of fifty professors from various medical disciplines at the university. The current rector of Karolinska Institute is Ole Petter Ottersen, who took office in August 2017.

Karolinska Institutet | |

| |

Former names | Kongl. Carolinska Medico Chirurgiska Institutet (1817–1968) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Att förbättra människors hälsa (Swedish) |

Motto in English | To improve human health |

| Type | Public |

| Established | 1810 |

| Endowment | 576,1 million EUR (2010) |

| Budget | SEK 6.67 billion[1] |

| Rector | Ole Petter Ottersen |

Administrative staff | 4,820 (2016)[1] |

| Students | 5,973 (FTE, 2016)[1] |

| 2,267 (2016)[1] | |

| Location | , , 59°20′56″N 18°01′36″E |

| Campus | Solna (Main) and Flemingsberg |

| Colors | KI Plum |

| Website | www |

The Karolinska Institute was founded in 1810 on the island of Kungsholmen on the west side of Stockholm; the main campus was relocated decades later to Solna, just outside Stockholm. A second campus was established more recently in Flemingsberg, Huddinge, south of Stockholm.[5] The Karolinska Institute is consistently ranked among the top medical universities internationally in a number of ranking tables.

The Karolinska Institute is Sweden's third oldest medical school, after Uppsala University (founded in 1477) and Lund University (founded in 1666). It is one of Sweden's largest centres for training and research, accounting for 30% of the medical training and more than 40% of all academic medical and life science research conducted in Sweden.[6]

The Karolinska University Hospital, located in Solna and Huddinge, is associated with the university as a research and teaching hospital. Together they form an academic health science centre. While most of the medical programs are taught in Swedish, the bulk of the PhD projects are conducted in English. The institute's name is a reference to the Caroleans.

History

19th century

The Karolinska Institute was founded by King Karl XIII on 13 December 1810 as an "academy for the training of skilled army surgeons" after one in three soldiers wounded in the Finnish War against Russia died in field hospitals. Indeed, a report of the time came to the conclusion that "the medical skills of the army barber-surgeons are manifestly inadequate, so Sweden needs to train surgeons in order to better prepare the country for future wars." Just one year later, in 1811, the Karolinska Institute was granted license to train not only surgeons but medical practitioners in general.

As one of KI's first professors, Jöns Jacob Berzelius laid the foundations of the newly inaugurated institute's scientific orientation, which in 1816 is granted the name Carolinska Institutet (in reference to the Caroleans[7]). This name, however, didn't really make an impact at the time and so was expanded to Carolinska Medico Chirurgiska institutet, which proved more popular, especially when preceded by the epithet Kongliga (Royal), as introduced in 1822. This original institute was situated in the Royal Bakery on Riddarholmen (a small but central island in Stockholm) and within a just a couple of years had grown to encompass four professorships in anatomy, natural history and pharmacy, theoretical medicine and practical medicine (internal medicine and surgery).

At around the same time Anders Johan Hagströmer, a professor of anatomy and surgery from the Collegium Medicum (the National Board of Health and Welfare of its day), was appointed the institute's first inspector, a post equivalent to today's president. In the same year, the institute moved to the old Glasbruk quarter on Norr Mälarstrand, beside what is now the City Hall. The move across the waters of Riddarfjärden was accomplished with the help of barges, one of which is said to have capsized, consigning parts of Hagströmer's collection of preparations to the lake bed. Despite this his library survives intact and today forms part of the KI-Swedish Society of Medicine museum at the institute's Hagströmer Library.

.jpg)

In 1861 the institute reached a significant milestone in being awarded the right to confer its own degrees; as such it was granted a status equal to that of a university. This, in turn, led to an increase in the size of the student body, necessitating the demolition of the old building on the Glasbruk plot and its replacement with a new, larger one. This new institute building was built in stages, mostly during the 1880s and into the first decade of the 20th century; it stands to this day, and has remained largely unchanged since its opening.

Although it had already gained the right to confer general degrees, KI wasn't licensed to confer medical degrees until 1874. Previously, even though the institute could run courses in medicine, the right to confer medical degrees was almost exclusively that of Uppsala University. Following on from this change in the institute's status the first doctoral thesis was defended at KI by Alfred Levertin, on the subject of "Om Torpa Källa". Just shortly thereafter the Medical Students' Union was formed.

The next decade was one of firsts. By 1880 the Karolinska Institute had started to accept women and so it was in 1884 that Karolina Widerström became the first woman to obtain a bachelor's degree in medicine from the institute; she later went on to obtain a Licentiate degree in medicine and chose to specialise in women's medicine and gynaecology. Anna Stecksén later became the first woman to obtain a doctorate from the university.

Just five years later, following the death of Alfred Nobel in 1895, the Karolinska Institute received the right to select the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Since then, this assignment has given the Karolinska Institute a broad contact network in the field of medical science. Indeed, over the years, five of the institute's own researchers have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

20th century

By 1930 the Swedish parliament had decided that a new teaching hospital was needed and resolved to build the new facility at Norrbacka in the Solna area of Stockholm. The hospital was, from the start, planned to have its theoretical and practical functions side by side, essentially signalling the start of the KI's move to the new site. The chief architect appointed to design the building, later to be named the Karolinska Hospital after a proposal by the Karolinska Institute, was Carl Westman. Westman worked tirelessly on this project, allowing for completion of the main hospital building by 1940. The hospital was officially opened in the same year along with the new Department of Public Health, KI's first building co-located with the hospital complex, and by 1945 KI moved the last of its departments from Kungsholmen to the Norrbacka site, known to current students and staff as the institute's Solna Campus.

The Karolinska Institute was initially slow to adopt social change. Nanna Svartz became the Karolinska Institute and Sweden's first state-employed female professor in 1937; she was the only female academic of this rank until Astrid Fagréus became the institute's second female professor almost thirty years later in 1965. However, by the mid-twentieth century student revolts were taking place regularly in the pursuit of greater social equality. It was in response to the largest of these revolts in 1968 that the name of the institute was shortened to the current form Karolinska Institutet, or KI.

_(2).jpg)

By the early 1970s the Huddinge Hospital became increasingly affiliated with the institute and, as more and more of the Karolinska Institute's departments start to move into the hospital buildings, the area developed to become what is KI's Huddinge campus today. It was here that the medical information centre for computer-based citation research (MIC) was set up, making the Karolinska Institute the first MEDLARS (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System) Centre outside the United States. Similarly innovative work continued at the institute throughout the 1970s, with Sweden's first toxicology programme commencing at KI in 1976 and the establishment of a psychotherapy course in 1979. Furthermore, in 1977 the Stockholm Institute of Physiotherapy closed, with the study programme transferring to a new physiotherapy department at KI.

In 1982 the Huddinge campus was expanded with the addition of the Novum Research Centre for the study of biotechnology, oral biology, nutrition and toxicology, and structural biochemistry. The number of departments was reduced from 150 to 30 in 1993 and programmes in optometry, biomedicine, and dental technology commenced. The other key feature of the 1990s was the institute's increasingly ambitious plans for commercialisation, as a result of which 'Karolinska Institutet Holding AB' and 'Karolinska Innovations AB' were formed to help the institute intensify its relations with the business community and facilitate scientists' attempts to commercialise their discoveries.

The year 1997 marked a major point in the history of the Karolinska Institute as it was finally granted official university status with a stated mission to "contribute to the improvement of human health through research, education and information". This newly acquired status later led to the incorporation of the Stockholm University of Health Sciences into KI, as a result of which seven new study programmes in occupational therapy, audionomy, midwifery, biomedical laboratory science, nursing, radiology nursing and dental hygiene, were added to KI's teaching portfolio. Around the same time the institute's public health science programme commenced bringing the total number of study programmes to nineteen. Similarly, by this point the institute possessed three student unions: The Medical Students' Union, the Dental Students' Union, and the Physiotherapy Students' Union.

21st century

.jpg)

With the turn of the millennium the Karolinska Institute sought to strengthen its activities in the field of external education and research, forming dedicated companies to help it do so and later establishing a fundraising campaign with a target of raising an extra 1 billion kronor for research between 2007 and 2010. During the same period new programmes were established in medical informatics, podiatry, and psychology as well as master's programmes of one and two years duration, and in 2004, the Karolinska Institute appointed its first female president – Harriet Wallberg-Henriksson, professor of integrative physiology.[8]

The year 2010 marked yet another significant event in the history of the KI as the institute celebrated its 200th anniversary under the patronage of King Carl XVI Gustaf. Shortly thereafter, the institute withdrew from the League of European Research Universities.[9] In 2013, Anders Hamsten assumed his new position as vice-chancellor of the Karolinska Institute, a position he held until when he resigned as in the wake of the Macchiarini affair.[10]

Nobel Prize winners

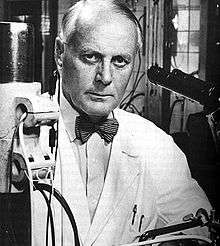

- 1955 Hugo Theorell becomes KI's first Nobel Laureate, receiving the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discoveries concerning the nature and mode of action of oxidation enzymes.

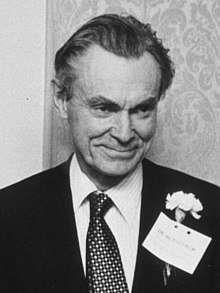

- 1967 Ragnar Granit receives the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his contributions to the analysis of retinal function and how optical nerve cells respond to light stimuli, colour and frequency.

- 1970 Ulf von Euler receives the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his contributions for discoveries concerning the humoral transmittors in the nerve terminals and the mechanism for their storage, release and inactivation.

- 1982 Sune Bergström and Bengt Samuelsson jointly receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries concerning prostaglandins and related biologically active substances.

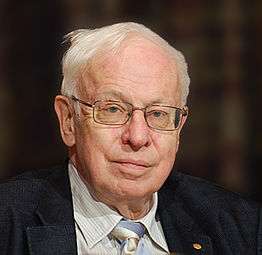

- 1981 Torsten Wiesel and David H. Hubel jointly receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries concerning information processing in the visual system.

Seal's symbolism

Rod of Asclepius

The rod of Asclepius is named after the god of medicine, Aesculapius or Asclepius. This ancient god was the son of Apollo and was generally accompanied by a snake. Over time, the snake became coiled around the staff borne by the god.

Snake bowl

The snake bowl was originally depicted together with Asclepius' daughter, the virgin goddess of health Hygieia or Hygiea. The snake ate from her bowl, which was considered to bring good fortune. There is nothing to support the notion that the snake would secrete its venom into the bowl.

Education

The Karolinska Institute offers the widest range of medical education under one roof in Sweden. Several of the programmes include clinical training or other training within the healthcare system. The close proximity of the Karolinska University Hospital and other teaching hospitals in the Stockholm area thus plays an important role during the education. Approximately 6,000 full-time students are taking educational and single subject courses at Bachelor and Master levels at the Karolinska Institute. Annually, 20 upper high school students from all over Sweden get selected to attend Karolinska's 7-week long biomedical summer research school, informally named "SoFo".

Departments

- Biosciences and Nutrition

- Cell and Molecular Biology

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Clinical Science and Education, Söder Hospital

- Clinical Science, Danderyd Hospital

- Clinical Sciences, Intervention and Technology

- Dental Medicine

- Environmental Medicine

- Laboratory Medicine

- Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics

- Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics

- Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics

- Medicine, Huddinge

- Medicine, Solna

- Microbiology, Tumour and Cell Biology

- Molecular Medicine and Surgery

- Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society

- Neuroscience

- Oncology-Pathology

- Physiology and Pharmacology

- Public Health Sciences

- Woman and Child Health

Rankings and reputation

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| Global – Overall | |

| ARWU World[11] | 38 |

| THE World[12] | 41 |

| THE Reputation[13] | 61–70 |

| USNWR Global[14] | 51 |

The Karolinska Institute is not listed in the overall QS World University Rankings since it only ranks multi-faculty universities. However, QS does rank the Karolinska Institute in the category of Medicine, placing it as the best in Sweden, 3rd in Europe and 6th worldwide in 2020.[15] In 2015, the QS ranked the Department of Dental Medicine 1st in the world.[16]

According to the 2020 Times Higher Education World University Rankings, the Karolinska Institute is ranked 12th worldwide and 5th in Europe in clinical, pre-clinical and other health subjects.[17]

The 2020 U.S. News & World Report Best Global University Ranking placed KI as 12th worldwide in Psychiatry and Psychology.[18]

In 2019, the Academic Ranking of World Universities ranked the Karolinska Institute in 4th place worldwide for pharmacy, 5th for public health, 6th for nursing, and 21st for clinical medicine .[19]

The university was a founding member of the League of European Research Universities.

Hong Kong donation controversy

In February 2015, the KI announced it had received a record $50 million donation from Lau Ming-wai, who chairs Hong Kong property developer Chinese Estates Holdings, and would establish a research centre in the city. Within a few days, Next Magazine revealed that Chuen-yan – son of Hong Kong Chief Executive CY Leung – had recently been awarded a fellowship to research heart disease therapeutics at the institute in Stockholm beginning that year, and raised questions about the "intricate relationship between the chief executive and powerful individuals". CY Leung had visited KI when in Sweden in 2014, and subsequently introduced KI president, Anders Hamsten, to Lau.[20][21] The Democratic Party urged the ICAC to investigate the donation, suggesting that Leung may have abused his public position to further his son's career. The Chief Executive's Office strenuously denied suggestions of any quid pro quo, saying that "the admission of the [Chief Executive's] son to post-doctoral research at KI is an independent decision by KI having regard to his professional standards. He [the son] plays no role and does not hold any position at the [proposed] Ming Wai Lau Center for Regenerative Medicine."[20] This accusation has also been questioned by the South China Morning Post's Canadian-based pro-Beijing and pro-government opinion columnist, Alex Lo: "The insinuation is that Leung Chuen-yan with a doctorate from Cambridge doesn't deserve his job at the Karolinska Institute...Leung the son probably could get similar junior posts in many other prestigious-sounding – at least to brand-obsessed Hongkongers – research institutes; it's not that big a deal."[22]

Scientific misconduct

The institute became infamous in the 2010s for its failure to prevent the deaths of seven patients at the hands of one of their star surgeons, Paolo Macchiarini, who was found to have repeatedly falsified medical data in order to perform unnecessary experimental surgeries that led the victims to painful deaths. Rather than investigating reports of scientific and ethical misconduct, the institute engaged in targeted retribution against the whistleblowers in an attempt to silence them.

In 2014, one of the institute's star surgeons, Paolo Macchiarini was accused by four former colleagues and co-authors of having falsified claims in his research.[23]

After repeatedly attempting to silence the whistleblowers, media coverage and public opinion finally forced the Institute to act, and in April 2015, the ethics committee of the institute issued a response to one set of allegations with regard to research ethics and peer review at the Lancet, and found them to be groundless.[24]

The Karolinska Institute had also appointed an external expert, Bengt Gerdin, to review the charges, comparing the results reported to the medical record of the hospital; the report was released by Karolinska in May 2015.[25][26][27] Gerdin found that Macchiarini had committed research misconduct in seven out of seven papers, by not getting ethical approval for the some of his operations, and misrepresenting the result of some of those operations, as well as work he had done in animals.[25][26][28]

In August 2015, after considering the findings and a rebuttal provided by Macchiarini, vice-chancellor of Karolinska Institute Anders Hamsten found that Macchiarini had acted "without due care" but had not committed misconduct.[29][30] The journal The Lancet, which published Macchiarini's work, also published an article defending Macchiarini.[31]

ON 5 January 2016, Vanity Fair published a story about Macchiarini romancing a journalist, which also called into question statements he had made on his CV.[32][33]

On 13 January 2016—the same day that the first part of a three-part documentary about Macchiarini would air on Swedish television—Gerdin criticized the vice-chancellor's dismissal of the allegations in an interview on Swedish television.[34]

Later that day, Sveriges Television investigative TV show Dokument inifrån started airing a three-part series, titled "Experimenten", in which Macchiarini's work was investigated.[32][35] The documentary shows Macchiarini continuing operations with the new method even after it showed little or no promise, exaggerating the health of his patients in articles as they died one by one. While Macchiarini admitted that the synthetic trachea did not work in the current state, he did not agree that trying it on several additional patients without further testing had been inappropriate. Allegations were also made that patients' medical conditions both before and after the operations, as reported in academic papers, did not match reality. Macchiarini also stated that the synthetic trachea had been tested on animals before using it on humans, something that could not be verified.[36][37][38]

On 28 January, Karolinska issued a statement saying that the documentary made claims of which it was unaware, and that it would consider re-opening the investigations.[39][40] These concerns were echoed by the chairman of the Karolinska Institute, Lars Leijonborg, and the chairman of the Swedish Medical Association, Heidi Stensmyren, calling for an independent investigation that would also look at how the issue was dealt with by the university and hospital management.[41]

In February 2016, the Karolinska Institute published a review of Macchiarini's CV that identified discrepancies.[42]

in February 2016 Karolinska announced that it would not renew Macchiarini's research contract, which was due to expire in November, and the next month Karolinska terminated the contract.[36]

In October 2016, the BBC broadcast a three-part Storyville documentary, Fatal Experiments: The Downfall of a Supersurgeon, directed by Bosse Lindquist and based on the earlier Swedish programmes about Macchiarini.[43]

After the special aired, the Karolinska Institute requested Sweden's national scientific review board to review six of Macchiarini's publications about the procedures. The board published its findings in October 2017, and concluded that all six were the result of scientific misconduct, in particular by failing to report the complications and deaths that occurred after the interventions; one of the articles also claimed that the procedure had been approved by an ethics committee, when this had not happened. The board called for all six of the papers to be retracted. It also said that all of the co-authors had committed scientific misconduct as well.[44]

Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute

_(2).jpg)

The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute is a body at the Karolinska Institute which awards the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. The Nobel Assembly consists of fifty professors in medical subjects at the Karolinska Institute, appointed by the faculty of the Institute, and is a private organisation which is formally not part of the Karolinska Institute. The main work involved in collecting nominations and screening nominees is performed by the Nobel Committee at the Karolinska Institute, which has five members. The Nobel Committee, which is appointed by the Nobel Assembly, is only empowered to recommend laureates, while the final decision rests with the Nobel Assembly.

In the early history of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, which was first awarded in 1901, the laureates were decided upon by the entire faculty of the Karolinska Institute. The reason for creating a special body for the decisions concerning the Nobel Prize was the fact that the Karolinska Institute is a state-run university, which in turn means that it is subject to various laws that apply to government agencies in Sweden and similar Swedish public sector organisations, such as freedom of information legislation. By moving the actual decision making to a private body at Karolinska Institute (but not part of it), it is possible to follow the regulations for the Nobel Prize set down by the Nobel Foundation, including keeping the confidentiality of all documents and proceedings for a minimum of 50 years. Also, the legal possibility of contesting the decisions in e.g. administrative courts is removed.

The other two Nobel Prize-awarding bodies in Sweden, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the Swedish Academy, are legally private organisations (although enjoying royal patronage), and have therefore not had to make any special arrangements to be able to follow the Nobel Foundation's regulations.

Notable alumni or faculty

.jpg)

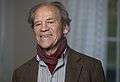

Pehr Edman

Pehr Edman

_nordisk_samarbetsminister_Sverige._Nordiska_radets_session_2010.jpg)

- Jöns Jakob Berzelius (1779–1848; professor at KI), invented modern chemical notation and is considered one of the fathers of modern chemistry; discoverer of the elements silicon, selenium, thorium, and cerium

- Carl Gustaf Mosander (1792–1858; student of chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius, his successor 1836), chemist, discoverer of the elements lanthanum, erbium and terbium.

- Gustaf Retzius (1842–1919), anatomist (professor 1877–1890)

- Karl Oskar Medin (1847–1928), paediatrician, famous for his study of poliomyelitis (professor 1883–1914)

- Wilhelm Netzel (1834–1914), Swedish researcher, gynecologist and obstetrician

- Ivar Wickman (1872–1914), pediatrician, pupil of Medin, polio expert

- Göran Liljestrand (1886–1968), physiologist and pharmacologist

- Nanna Svartz (1890–1986), first female professor at Karolinska Institute and, as a result, the first woman to be appointed professor at a public university in Sweden ever; researcher in gastrointestinal diseases and rheumatologist

- die Ulf von Euler (1905–1983), physiologist, Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine in 1970

- Herbert Olivecrona (1891–1980), founder of Swedish neurosurgery

- Ragnar Granit (1900–1991), Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine in 1967

- Hugo Theorell (1903–1982), Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine in 1955

- Lars Leksell (1907–1986), physician, inventor of radiosurgery and the Gamma Knife

- Sune Bergström (1916–2004), Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine in 1982 (with Bengt I. Samuelsson and John Robert Vane)

- Pehr Edman (1916–1977), chemist (Med. dr 1946). Cf. Edman degradation

- Sven Ivar Seldinger (1921–1998), radiologist, inventor of the Seldinger technique

- Torsten Wiesel (born 1924), Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine in 1981

- Bengt I. Samuelsson (born 1934), Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine in 1982 (with Sune Bergström and John Robert Vane)

- Tomas Lindahl, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry in 2015 (with Paul Modrich and Aziz Sancar), cancer researcher and winner of the Royal Medal

- Lennart Nilsson (1922–2017), computational biologist, photojournalist, and Emmy-award-winning documentarian

- Johan Harmenberg (born 1954), Olympic champion épée fencer

See also

- Karolinska Institute Prize for Research in Medical Education

- Sahlgrenska University Hospital

- Royal Institute of Technology

- Stockholm School of Economics

- Stockholm University

- The New Karolinska Solna University Hospital, opened in 2015

- S*, a collaboration between seven universities and the Karolinska Institute

References

- "KI in brief".

- Karolinska Institutets Varumärkesplattform (Swedish) Revised Nov 2014, Page 6 https://ki.se/sites/default/files/vmplattform_nov2014_4_0_180117.pdf

- Nobel Foundation Directory. 2003. Stockholm : Nobel Foundation, p. 5.

- National Council of Science Museums. 2005. Nobel Prize Winners in Pictures with CD-ROM. Delhi: Foundation Books, p. v.

- http://ki.se/en/about/ki-through-the-centuries retrieved: 8 June 2015

- "Research at Karolinska". Archived from the original on 13 March 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Risling M, Bellander BM, Cullheim S (2012). "Traumatic injuries in the nervous system". Front Neurol. 3: 26. doi:10.3389/fneur.2012.00026. PMC 3285774. PMID 22375136.

- "KI through the centuries".

- The First Decade

- "Anders Hamsten steps down as Vice-Chancellor of Karolinska Institutet". Karolinska Institutet. 12 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Academic Ranking of World Universities 2019

- World University Rankings 2019

- US News Rankings 2010

- "QS World University Rankings 2020 Results". QS World University Rankings. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "QS World University Ranking for Dentistry".

- "World University Rankings 2020 by subject: clinical, pre-clinical and health". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "US News and World Report Best Global University Ranking". US News and World Report. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Academic Ranking of World Universities". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Karolinska's Asia campus donation questioned – University World News".

- "CY denies link over son's job and $400m donation" Archived 26 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. The Standard, 17 February 2015

- "Next Magazine misses the mark in saying money, influence behind Leung Chuen-yan getting post at Karolinska Institute". South China Morning Post, 22 February 2015

- Fountain, Henry (24 November 2014). "Leading Surgeon Is Accused of Misconduct in Experimental Transplant Operations". The New York Times.

- ""Super-surgeon" Macchiarini not guilty of misconduct, per one Karolinska investigation". Retraction Watch. 14 April 2015.

- Vogel, Gretchen (19 May 2015). "Report finds trachea surgeon committed misconduct". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aac4623.

- Vogel, Gretchen (27 May 2015). "Karolinska releases English translation of misconduct report on trachea surgeon". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aac4649.

- "Gerdin Report (English) Assignment ref: 2-2184/2014" (PDF). Karolinska via CIRCARE. 13 May 2015.

- Cyranoski, David (2015). "Artificial-windpipe surgeon committed misconduct". Nature. 521 (7553): 406–407. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..406C. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.17605. PMID 26017424.

- "Trachea surgeon Macchiarini acted "without due care," but is not guilty of misconduct: Karolinska". Retraction Watch. 28 August 2015.

- Keisu, Claes (28 August 2015). "Visiting Professor at Karolinska Institutet cleared from suspicions of scientific misconduct". Karolinska Institutet. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- The Lancet (2015). "Paolo Macchiarini is not guilty of scientific misconduct". The Lancet. 386 (9997): 932. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00118-X. PMID 26369448.

- "Reading about embattled trachea surgeon Paolo Macchiarini? Here's what you need to know". Retraction Watch. 12 February 2016.

- Ciralsky, Adam (31 January 2016). "The Celebrity Surgeon Who Used Love, Money, and the Pope to Scam an NBC News Producer". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Hallbom, Johannes; Moberger, Karin (13 January 2016). "Utredaren står fast – KI:s stjärnkirurg har forskningsfuskat" [The investigator stands firm – The KI's star surgeon accused of research fraud] (in Swedish). Sveriges Television.

- "Experimenten: Stjärnkirurgen" [The Experiments: The Star Surgeon]. Dokument inifrån. Sveriges Television. 7 January 2016.

- Abbott, Alison (2016). "Prestigious Karolinska Institute dismisses controversial trachea surgeon". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19629.

- Enserink, Martin (2016). "Karolinska Institute fires fallen star surgeon Paolo Macchiarini". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aaf9825.

- Kremer, William (10 September 2016). "Paolo Macchiarini: A surgeon's downfall". BBC News.

- "Karolinska may reopen inquiry into star surgeon Macchiarini, following documentary's revelations". Retraction Watch. 1 February 2016.

- "Comment on the TV documentary "Experimenten"". Karolinska Institute. 28 January 2016.

- Andersson, Carl V (1 February 2016). "KI:s ledning granskas av oberoende utredning" [KI's management reviewed by independent investigation]. Dagens Medicin (in Swedish).

- "Examination of CV information" (PDF). Karolinska Institute. 11 February 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2016.

- "Fatal Experiments: The Downfall of a Supersurgeon". BBC Online. BBC. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- Vogel, Gretchen (2017). "Six papers by disgraced surgeon should be retracted, report concludes". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aar3612.

External links

- Karolinska Institute – Official site