Icaridin

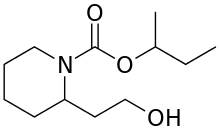

Icaridin, also known as picaridin, is an insect repellent which can be used directly on skin or clothing.[1] It has broad efficacy against various insects and ticks and is almost colorless and odorless.

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

IUPAC name

| |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.102.177 | ||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C12H23NO3 | |||

| Molar mass | 229.320 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | colorless liquid | ||

| Odor | odorless | ||

| Density | 1.07 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 170 °C (338 °F; 443 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 296 °C (565 °F; 569 K) | ||

| 0.82 g/100 mL | |||

| Solubility | 752 g/100mL (acetone) | ||

Refractive index (nD) |

1.4717 | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

The name picaridin was proposed as an International Nonproprietary Name (INN) to the World Health Organization (WHO), but the official name that has been approved by the WHO is icaridin. The chemical is part of the piperidine family,[1] along with many pharmaceuticals and alkaloids such as piperine, which gives black pepper its spicy taste.

Trade names include Bayrepel and Saltidin among others. The compound was developed by the German chemical company Bayer and was given the name Bayrepel. In 2005, Lanxess AG and its subsidiary Saltigo GmbH were spun off from Bayer[2] and the product was renamed Saltidin in 2008.[3]

Effectiveness

Icaridin has been reported to be as effective as DEET without the irritation associated with DEET.[4] According to the WHO, icaridin “demonstrates excellent repellent properties comparable to, and often superior to, those of the standard DEET.” In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using repellents based on icaridin, DEET, ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate (IR3535), or oil of lemon eucalyptus (containing p-menthane-3,8-diol, PMD) for effective protection against mosquitoes that carry the West Nile virus, Eastern Equine Encephalitis and other illnesses.[5]

Icaridin does not dissolve plastics.[6]

Icaridin-based products, first used in Europe in 2001, have been evaluated by Consumer Reports in 2016 as among the most effective insect repellents when used at a 20% concentration.[7] Icaridin was earlier reported to be effective by Consumer Reports (7% solution)[8] and the Australian Army (20% solution).[9] Consumer Reports retests in 2006 gave as result that a 7% solution of icaridin offered little or no protection against Aedes mosquitoes (vector of dengue fever) and a protection time of about 2.5 hours against Culex (vector of West Nile virus), while a 15% solution was good for about one hour against Aedes and 4.8 hours against Culex.[10]

Larval salamander toxicity

A 2018 study found that icaridin, in what the authors described as conservative exposure doses, is highly toxic to salamander larvae.[11]

The study observed high larval salamander mortality occurring delayed after the four days of exposure. Because the widely used LC50 test for assessing a chemical's environmental toxicity is based on mortality within four days, icaridin would be incorrectly deemed as "safe" under the test protocol.[12]

Chemistry

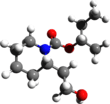

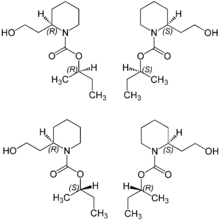

Icaridin contains two stereocenters: one where the hydroxyethyl chain attaches to the ring, and one where the sec-butyl attaches to the oxygen of the carbamate. The commercial material contains a mixture of all four stereoisomers.

Commercial products

Commercial products containing icaridin include Cutter Advanced, Skin So Soft Bug Guard Plus, Autan, Smidge, PiActive and MOK.O.[13]

Mechanism

A potential odorant receptor for Ιcaridin (and DEET), the CquiOR136•CquiOrco, has been suggested recently for Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito. [14]

Recent crystal and solution studies showed that Icaridin binds to Anopheles gambiae odorant binding protein 1 (AgamOBP1). The crystal structure of AgamOBP1•Icaridin complex (PDB: 5EL2) revealed that Icaridin binds to the DEET-binding site in two distinct orientations and also to a second binding site (sIC-binding site) located at the C-terminal region of the AgamOBP1.[15]

Recent evidence with Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes suggests icaridin does not strongly activate olfactory receptors neurons, but instead functions to reduce the volatility of the odorants to which it is mixed.[16] By reducing odor volatility, icaridin functions to "mask" the ability of volatile odorants on the skin to activate olfactory neurons and attract mosquitoes.[16]

See also

- SS220, another substituted-piperidine insect repellent

References

- "Picaridin". npic.orst.edu. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- "Bayer Completes Spin Off of Lanxess AG". 31 January 2005.

- Saltigo renames insect repellant, Chemical & Engineering News

- Journal of Drugs in Dermatology (Jan-Feb 2004) http://jddonline.com/articles/dermatology/S1545961604P0059X/1

- "Traveler's Health: Avoid bug bites". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Picaridin. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011.

- "Mosquito Repellents That Best Protect Against Zika". Consumer Reports, April, 2016.

- - Consumer Reports Confirms Effectiveness Of New Alternative To Deet (link recreated from Wayback Machine Internet Archive - 19 May 2019)

- Frances, S. P.; Waterson, D. G. E.; Beebe, N. W.; Cooper, R. D. (2004). "Field Evaluation of Repellent Formulations Containing Deet and Picaridin Against Mosquitoes in Northern Territory, Australia". Journal of Medical Entomology. 41 (3): 414–7. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-41.3.414. PMID 15185943.

- "Insect repellents: which keep bugs at bay?" Consumer Reports, June 2006, vol 71 (issue 6), p. 6.

- Almeida, Rafael; Han, Barbara; Reisinger, Alexander; Kagemann, Catherine; Rosi, Emma (1 October 2018). "High mortality in aquatic predators of mosquito larvae caused by exposure to insect repellent". Biology Letters. 14 (10): 20180526. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2018.0526. PMC 6227861. PMID 30381452.

- "Widely used mosquito repellent proves lethal to larval salamanders". Science News. ScienceDaily. Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. 31 October 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Cha, Ariana Eunjung. "Zika virus FAQ: What is it, and what are the risks as it spreads? The Washington Post. January 21, 2016.

- Xu, Pingxi; Choo, Young-Moo; de la Rosa, Alyssa; Leal, Walter S. (2014). "Mosquito odorant receptor for DEET and methyl jasmonate". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (46): 16592–16597. doi:10.1073/pnas.1417244111. PMC 4246313. PMID 25349401.

- Drakou, CE; Tsitsanou, KE; Potamitis, C; Fessas, D; Zervou, M; Zographos, SE (2017). "The crystal structure of the AgamOBP1•Icaridin complex reveals alternative binding modes and stereo-selective repellent recognition". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 74 (2): 319–338. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2335-6. PMID 27535661.

- Afify, Ali; Betz, Joshua F.; Riabinina, Olena; Lahondère, Chloé; Potter, Christopher J. (2019). "Commonly Used Insect Repellents Hide Human Odors from Anopheles Mosquitoes". Current Biology. 29 (21): 3669–3680.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.09.007. PMC 6832857. PMID 31630950.