Left-wing politics

Left-wing politics supports social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy.[1][2][3][4] It typically involves a concern for those in society whom its adherents perceive as disadvantaged relative to others as well as a belief that there are unjustified inequalities that need to be reduced or abolished.[1]

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||

| Party politics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political spectrum | ||||||

|

||||||

| Party platform | ||||||

| Party organization | ||||||

|

||||||

| Party system | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Coalition | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Lists | ||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||

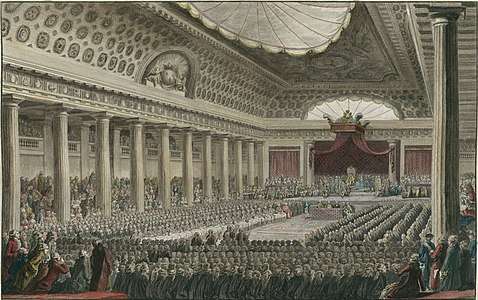

The political terms Left and Right were coined during the French Revolution (1789–1799), referring to the seating arrangement in the French Estates General. Those who sat on the left generally opposed the monarchy and supported the revolution, including the creation of a republic and secularization,[5] while those on the right were supportive of the traditional institutions of the Old Regime. Use of the term Left became more prominent after the restoration of the French monarchy in 1815 when it was applied to the "Independents".[6] The word "wing" was appended to Left and Right in the late 19th century, usually with disparaging intent and "left-wing" was applied to those who were unorthodox in their religious or political views.

The term was later applied to a number of movements, especially republicanism during the French Revolution in the 18th century, followed by socialism,[7] including anarchism, communism and social democracy, in the 19th and 20th centuries.[8] Since then, the term left-wing has been applied to a broad range of movements[9] including civil rights movements, feminist movements, anti-war movements and environmental movements,[10][11] as well as a wide range of parties.[12][13][14] According to emeritus professor of economics, Barry Clark, "[leftists] claim that human development flourishes when individuals engage in cooperative, mutually respectful relations that can thrive only when excessive differences in status, power, and wealth are eliminated".[15]

History

In politics, the term Left derives from the French Revolution, as the anti-monarchist Montagnard and Jacobin deputies from the Third Estate generally sat to the left of the presiding member's chair in parliament, a habit which began in the French Estates General of 1789. Throughout the 19th century in France, the main line dividing Left and Right was between supporters of the French Republic and those of the monarchy.[5] The June Days uprising during the Second Republic was an attempt by the Left to assert itself after the 1848 Revolution, but only a small portion of the population supported this.

In the mid-19th century, nationalism, socialism, democracy and anti-clericalism became features of the French Left. After Napoleon III's 1851 coup and the subsequent establishment of the Second Empire, Marxism began to rival radical republicanism and utopian socialism as a force within left-wing politics. The influential Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, published in 1848, asserted that all human history is the history of class struggle. They predicted that a proletarian revolution would eventually overthrow bourgeois capitalism and create a classless, stateless, post-monetary communist society. It was in this period that the word "wing" was appended to both Left and Right.[16]

In the United States, many leftists, social liberals, progressives and trade unionists were influenced by the works of Thomas Paine, who introduced the concept of asset-based egalitarianism, which theorises that social equality is possible by a redistribution of resources.

The International Workingmen's Association (1864–1876), sometimes called the First International, brought together delegates from many different countries, with many different views about how to reach a classless and stateless society. Following a split between supporters of Marx and Mikhail Bakunin, anarchists formed the International Workers' Association.[17] The Second International (1888–1916) became divided over the issue of World War I. Those who opposed the war, such as Vladimir Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg, saw themselves as further to the left.

In the United States after Reconstruction, the phrase "the Left" was used to describe those who supported trade unions, the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement.[18][19] More recently in the United States, left-wing and right-wing have often been used as synonyms for Democratic and Republican, or as synonyms for liberalism and conservatism respectively.[20][21][22][23]

Since the Right was populist, both in the Western and the Eastern Bloc anything viewed as avant-garde art was called leftist in all Europe, thus the identification of Picasso's Guernica as "leftist" in Europe[24] and the condemnation of the Russian composer Shostakovich's opera (The Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District) in Pravda as follows: "Here we have 'leftist' confusion instead of natural, human music".[25]

Positions

The following positions are typically associated with left-wing politics.

Economics

Leftist economic beliefs range from Keynesian economics and the welfare state through industrial democracy and the social market to nationalization of the economy and central planning,[26] to the anarcho-syndicalist advocacy of a council- and assembly-based self-managed anarchist communism. During the Industrial Revolution, leftists supported trade unions. At the beginning of the 20th century, many leftists advocated strong government intervention in the economy.[27] Leftists continue to criticize what they perceive as the exploitative nature of globalization, the "race to the bottom" and unjust lay-offs. In the last quarter of the 20th century, the belief that government (ruling in accordance with the interests of the people) ought to be directly involved in the day-to-day workings of an economy declined in popularity amongst the center-left, especially social democrats who became influenced by "Third Way" ideology.

Other leftists believe in Marxian economics, which are based on the economic theories of Karl Marx. Some distinguish Marx's economic theories from his political philosophy, arguing that Marx's approach to understanding the economy is independent of his advocacy of revolutionary socialism or his belief in the inevitability of proletarian revolution.[28][29] Marxian economics does not exclusively rely upon Marx, but it draws from a range of Marxist and non-Marxist sources. The dictatorship of the proletariat or workers' state are terms used by some Marxists, particularly Leninists and Marxist–Leninists, to describe what they see as a temporary state between the capitalist state of affairs and a communist society. Marx defined the proletariat as salaried workers, in contrast to the "lumpenproletariat", who he defined as outcasts of society, such as beggars, tricksters, entertainers, buskers, criminals and prostitutes.[30] The political relevance of farmers has divided the left. In Das Kapital, Marx scarcely mentioned the subject.[31] Mao Zedong believed that it would be rural peasants, not urban workers, who would bring about the proletarian revolution.

Left-libertarians, libertarian socialists and anarchists believe in a decentralized economy run by trade unions, workers' councils, cooperatives, municipalities and communes and oppose both state and private control of the economy, preferring social ownership and local control, in which a nation of decentralized regions is united in a confederation.

The global justice movement, also known as the anti-globalization movement or alter-globalization movement, protests against corporate economic globalization due to its negative consequences for the poor, workers, the environment and small businesses.[32][33][34]

Environment

One of the foremost left-wing advocates was Thomas Paine, one of the first individuals since left and right became political terms to describe the collective human ownership of the world which he speaks of in Agrarian Justice.[35] As such, most of left-wing thought concerning environmentalism stems from this duty of ownership, and this cooperative ownership means that we need to take care of it. This is reflected in much of the historical left-wing thought that came after, although there were disagreements about what this entailed.

Both Karl Marx and the early socialist William Morris arguably had a concern for environmental matters.[36][37][38][39] According to Marx: "Even an entire society, a nation, or all simultaneously existing societies taken together [...] are not owners of the earth. They are simply its possessors, its beneficiaries, and have to bequeath it in an improved state to succeeding generations".[36][40] Following the Russian Revolution, environmental scientists such as revolutionary Alexander Bogdanov and the Proletkult organisation made efforts to incorporate environmentalism into Bolshevism and "integrate production with natural laws and limits" in the first decade of Soviet rule, before Joseph Stalin attacked ecologists and the science of ecology, purged environmentalists and promoted the pseudo-science of Trofim Lysenko.[41][42][43] Similarly, Mao Zedong rejected environmentalism and believed that based on the laws of historical materialism all of nature must be put into the service of revolution.[44]

From the 1970s onwards, environmentalism became an increasing concern of the left, with social movements and some unions campaigning over environmental issues. For example, the left-wing Builders Labourers Federation in Australia, led by the communist Jack Mundy, united with environmentalists to place green bans on environmentally destructive development projects.[45] Some segments of the socialist and Marxist left consciously merged environmentalism and anti-capitalism into an eco-socialist ideology.[46] Barry Commoner articulated a left-wing response to The Limits to Growth model that predicted catastrophic resource depletion and spurred environmentalism, postulating that capitalist technologies were chiefly responsible for environmental degradation, as opposed to population pressures.[47] Environmental degradation can be seen as a class or equity issue, as environmental destruction disproportionately affects poorer communities and countries.[48]

Several left-wing or socialist groupings have an overt environmental concern and several green parties contain a strong socialist presence. For example, the Green Party of England and Wales features an eco-socialist group, Green Left, that was founded in June 2005. Its members held some influential positions within the party, including both the former Principal Speakers Siân Berry and Dr. Derek Wall, himself an eco-socialist and Marxist academic.[49] In Europe, some Green left political parties combine traditional social-democratic values such as a desire for greater economic equality and workers rights with demands for environmental protection, such as the Nordic Green Left.

Well-known socialist Bolivian President Evo Morales has traced environmental degradation to consumerism.[50] He has said: "The Earth does not have enough for the North to live better and better, but it does have enough for all of us to live well". James Hansen, Noam Chomsky, Raj Patel, Naomi Klein, The Yes Men and Dennis Kucinich have had similar views.[51][52][53][54][55][56]

In the 21st century, questions about the environment have become increasingly politicized, with the Left generally accepting the findings of environmental scientists about global warming[57][58] and many on the Right disputing or rejecting those findings.[59][60][61] However, the left is divided over how to effectively and equitably reduce carbon emissions: the center-left often advocates a reliance on market measures such as emissions trading or a carbon tax, while those further to the left tend to support direct government regulation and intervention either alongside or instead of market mechanisms.[62][63][64]

Nationalism and anti-nationalism

The question of nationality and nationalism has been a central feature of political debates on the Left. During the French Revolution, nationalism was a policy of the Republican Left.[65] The Republican Left advocated civic nationalism[5] and argued that the nation is a "daily plebiscite" formed by the subjective "will to live together". Related to "revanchism", the belligerent will to take revenge against Germany and retake control of Alsace-Lorraine, nationalism was sometimes opposed to imperialism. In the 1880s, there was a debate between those, such as Georges Clemenceau (Radical), Jean Jaurès (Socialist) and Maurice Barrès (nationalist), who argued that colonialism diverted France from the "blue line of the Vosges" (referring to Alsace-Lorraine); and the "colonial lobby", such as Jules Ferry (moderate republican), Léon Gambetta (republican) and Eugène Etienne, the president of the parliamentary colonial group. After the Dreyfus Affair, nationalism instead became increasingly associated with the far-right.[66]

The Marxist social class theory of proletarian internationalism asserts that members of the working class should act in solidarity with working people in other countries in pursuit of a common class interest, rather than focusing on their own countries. Proletarian internationalism is summed up in the slogan: "Workers of the world, unite!", the last line of The Communist Manifesto. Union members had learned that more members meant more bargaining power. Taken to an international level, leftists argued that workers ought to act in solidarity to further increase the power of the working class.

Proletarian internationalism saw itself as a deterrent against war, because people with a common interest are less likely to take up arms against one another, instead focusing on fighting the ruling class. According to Marxist theory, the antonym of proletarian internationalism is bourgeois nationalism. Some Marxists, together with others on the left, view nationalism,[67] racism[68] (including anti-Semitism)[69] and religion as divide and conquer tactics used by the ruling classes to prevent the working class from uniting against them. Left-wing movements therefore have often taken up anti-imperialist positions. Anarchism has developed a critique of nationalism that focuses on nationalism's role in justifying and consolidating state power and domination. Through its unifying goal, nationalism strives for centralization, both in specific territories and in a ruling elite of individuals, while it prepares a population for capitalist exploitation. Within anarchism, this subject has been treated extensively by Rudolf Rocker in Nationalism and Culture and by the works of Fredy Perlman, such as Against His-Story, Against Leviathan and The Continuing Appeal of Nationalism.[70]

The failure of revolutions in Germany and Hungary ended Bolshevik hopes for an imminent world revolution and led to promotion of "Socialism in One Country" by Joseph Stalin. In the first edition of the book Osnovy Leninizma (Foundations of Leninism, 1924), Stalin argued that revolution in one country is insufficient, but by the end of that year in the second edition of the book he argued that the "proletariat can and must build the socialist society in one country". In April 1925, Nikolai Bukharin elaborated the issue in his brochure Can We Build Socialism in One Country in the Absence of the Victory of the West-European Proletariat?, whose position was adopted as state policy after Stalin's January 1926 article On the Issues of Leninism (К вопросам ленинизма). This idea was opposed by Leon Trotsky and his followers who declared the need for an international "permanent revolution". Various Fourth Internationalist groups around the world who describe themselves as Trotskyist see themselves as standing in this tradition, while Maoist China supported Socialism in One Country.

European social democrats strongly support Europeanism and supranational integration, although there is a minority of nationalists and eurosceptics also in the left. Some link this left-wing nationalism to the pressure generated by economic integration with other countries encouraged by free trade agreements. This view is sometimes used to justify hostility towards supranational organizations. Left-wing nationalism can also refer to any nationalism which emphasises a working-class populist agenda which seeks to overcome perceived exploitation or oppression by other nations. Many Third World anti-colonial movements adopted left-wing and socialist ideas.

Third-Worldism is a tendency within leftist thought that regards the division between First World developed countries and Third World developing countries as being of high political importance. This tendency supports national liberation movements against what it considers imperialism by capitalists. Third-Worldism is closely connected with African socialism, Latin American socialism, Maoism,[71] Pan-Africanism and Pan-Arabism. Some left-wing groups in the developing world – such as the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in Mexico, the Abahlali baseMjondolo in South Africa and the Naxalites in India – argue that the First World Left takes a racist and paternalistic attitude towards liberation movements in the Third World.

Religion

The original French left-wing was anti-clerical, opposing the influence of the Roman Catholic Church and supporting the separation of church and state.[5] Karl Marx asserted that "[r]eligion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people".[72] In Soviet Russia, the Bolsheviks originally embraced "an ideological creed which professed that all religion would atrophy" and "resolved to eradicate Christianity as such". In 1918, "ten Orthodox hierarchs were summarily shot" and "children were deprived of any religious education outside the home".[73] Today in the Western world those on the Left usually support secularization and the separation of church and state.

However, religious beliefs have also been associated with some left-wing movements, such as the civil rights movement and the anti-capital punishment movement. Early socialist thinkers such as Robert Owen, Charles Fourier and the Comte de Saint-Simon based their theories of socialism upon Christian principles. From St. Augustine of Hippo's City of God through St. Thomas More's Utopia, major Christian writers defended ideas that socialists found agreeable. Other common leftist concerns such as pacifism, social justice, racial equality, human rights and the rejection of excessive wealth can be found in the Bible.[74] In the late 19th century, the Social Gospel movement arose (particularly among some Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists and Baptists in North America and Britain) which attempted to integrate progressive and socialist thought with Christianity in faith-based social activism, promoted by movements such as Christian socialism. In the 20th century, the theology of liberation and Creation Spirituality was championed by such writers as Gustavo Gutierrez and Matthew Fox.

Other left-wing religious movements include Islamic socialism and Buddhist socialism. There have been alliances between the left and anti-war Muslims, such as the Respect Party and the Stop the War Coalition in Britain. In France, the left has been divided over moves to ban the hijab from schools, with some supporting a ban based on separation of church and state and others opposing the prohibition based on personal freedom.

Social progressivism and counterculture

Social progressivism is another common feature of modern leftism, particularly in the United States, where social progressives played an important role in the abolition of slavery,[75] women's suffrage,[76] civil rights and multiculturalism. Progressives have both advocated prohibition legislation and worked towards its repeal. Current positions associated with social progressivism in the West include opposition to the death penalty and the War on Drugs, support for abortion rights, cognitive liberty, LGBT rights including legal recognition of same-sex marriage, distribution of contraceptives, and public funding of embryonic stem-cell research. Public education was a subject of great interest to groundbreaking social progressives such as Lester Frank Ward and John Dewey, who believed that a democratic system of government was impossible without a universal and comprehensive system of education.

Various counterculture movements in the 1960s and 1970s were associated with the "New Left". Unlike the earlier leftist focus on union activism, the New Left instead adopted a broader definition of political activism commonly called social activism. The New Left in the United States is associated with the hippie movement, college campus mass protest movements, and a broadening of focus from protesting class-based oppression to include issues such as gender, race and sexual orientation. The British New Left was an intellectually driven movement which attempted to correct the perceived errors of "Old Left".

The New Left opposed prevailing authority structures in society, which it termed "The Establishment" and became known as "anti-Establishment". The New Left did not seek to recruit industrial workers but rather concentrated on a social activist approach to organization, convinced that they could be the source for a better kind of social revolution. This view has been criticised by some Marxists (especially Trotskyists) who characterized this approach as "substitutionism", which they described as a misguided and non-Marxist belief that other groups in society could "substitute" for the revolutionary agency of the working class.[77][78]

Many early feminists and advocates of women's rights were considered left-wing by contemporaries. Feminist pioneer Mary Wollstonecraft was influenced by the radical thinker Thomas Paine. Many notable leftists have been strong supporters of gender equality, such as the Marxists Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin, and Alexandra Kollontai; anarchists such as Virginia Bolten, Emma Goldman, and Lucía Sánchez Saornil; and socialists Helen Keller and Annie Besant.[79] However, Marxists such as Rosa Luxemburg,[80] Clara Zetkin[81][82] and Alexandra Kollontai,[83][84] though supporters of radical social equality for women, opposed feminism because they considered it to be a bourgeois ideology. Marxists were responsible for organizing the first International Working Women's Day events.[85]

The women's liberation movement is closely connected to the New Left and other new social movements that challenged the orthodoxies of the Old Left. Socialist feminism, as exemplified by the Freedom Socialist Party and Radical Women; and Marxist feminism, as with Selma James, saw themselves as a part of the left that challenged what they perceive to be male-dominated and sexist structures within the Left. Liberal feminism is closely connected with social liberalism, and in America, with the left wing of mainstream politics (e.g., National Organization for Women).

The connection between left-leaning ideologies and LGBT rights struggles also has an important history. Prominent socialists who were involved in early struggles for LGBT rights include Edward Carpenter, Oscar Wilde, Harry Hay, Bayard Rustin, and Daniel Guérin, among others.

Varieties

The spectrum of left-wing politics ranges from center-left to far-left (or ultra-left). The term center-left describes a position within the political mainstream. The terms far-left and ultra-left refer to positions that are more radical. The center-left includes social democrats, social liberals, progressives and also some democratic socialists and greens (including some eco-socialists). Center-left supporters accept market allocation of resources in a mixed economy with a significant public sector and a thriving private sector. Center-left policies tend to favour limited state intervention in matters pertaining to the public interest.

In several countries, the terms far-left and radical left have been associated with varieties of communism, autonomism and anarchism. They have been used to describe groups that advocate anti-capitalism or eco-terrorism. In France, a distinction is made between the left (Socialist Party and Communist Party) and the far-left (Trotskyists, Maoists and anarchists).[86] The United States Department of Homeland Security defines left-wing extremism as groups that want "to bring about change through violent revolution rather than through established political processes".[87]

In China, the term Chinese New Left denotes those who oppose the current economic reforms and favour the restoration of more socialist policies.[88] In the Western world, the term New Left refers to cultural politics. In the United Kingdom in the 1980s, the term hard left was applied to supporters of Tony Benn, such as the Campaign Group and those involved in the London Labour Briefing newspaper, as well as Trotskyist groups such as Militant and the Alliance for Workers' Liberty.[89] In the same period, the term soft left was applied to supporters of the British Labour Party who were perceived to be more moderate. Under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, the British Labour Party rebranded itself as New Labour in order to promote the notion that it was less left-wing than it had been in the past. One of the first actions of the Labour Party leader who succeeded them, Ed Miliband, was the rejection of the "New Labour" label. However, Labour's voting record in parliament would indicate that under Miliband it had maintained the same distance from the left as it had with Blair.[90][91] Likewise, the election of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour Party leader was viewed by some as Labour turning back toward its socialist roots.

Leftist postmodernism opposes attempts to supply universal explanatory theories, including Marxism, deriding them as grand narratives. It views culture as a contested space and via deconstruction seeks to undermine all pretensions to absolute truth. Left-wing critics of post-modernism assert that cultural studies inflates the importance of culture by denying the existence of an independent reality.[92][93]

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Leftism |

- Authoritarian socialism

- Conflict theory

- Dirtbag left

- History of trade unions in the United Kingdom

- Labor history of the United States

- List of left-wing internationals

- List of left-wing political parties

- Political correctness

- Post-left anarchy

- Redistribution (economics)

- Red scare

- Redwashing

- Regressive left

- Social criticism

- Social justice warrior

- Syndicalism

- The Internationale

References

- Smith, T. Alexander; Tatalovich, Raymond (2003). Cultures at War: Moral Conflicts in Western Democracies. Toronto, Canada: Broadview Press. p. 30.

- Bobbio, Norberto; Cameron, Allan (1997). Left and Right: The Significance of a Political Distinction. University of Chicago Press. p. 37.

- Ball, Terence (2005). The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century Political Thought (Reprint. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 614. ISBN 9780521563543. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Thompson, Willie (1997). The Left In History: Revolution and Reform in Twentieth-Century Politic. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0745308913.

- Knapp, Andrew; Wright, Vincent (2006). The government and politics of France (5th ed.). London [u.a.]: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35732-6.

the government and politics of france.

- Realms of memory: conflicts and divisions (1996), ed. Pierre Nora, "Right and Left" by Marcel Gauchet, p. 248.

- Maass, Alan; Zinn, Howard (2010). The Case for Socialism (Revised ed.). Haymarket Books. p. 164. ISBN 978-1608460731.

The International Socialist Review is one of the best left-wing journals around...

- Schmidt, Michael; Van der Walt, Lucien (2009). Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism. Counter-Power. 1. AK Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-904859-16-1.

[...] anarchism is a coherent intellectual and political current dating back to the 1860s and the First International, and part of the labour and left tradition

- Revel, Jean Francois (2009). Last Exit to Utopia. Encounter Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-1594032646.

In the United States, the word liberal is often used to describe the left wing of the Democratic party.

- Neumayer, Eric (2004). "The environment, left-wing political orientation, and ecological economics" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 51 (3–4): 167–175. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.06.006.

- Barry, John (2002). International Encyclopedia of Environmental Politics. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0415202855.

All surveys confirm that environmental concern is associated with green voting...[I]n subsequent European elections, green voters have tended to be more left-leaning...the party is capable of motivating its core supporters as well as other environmentally minded voters of predominantly left-wing persuasion...

- "Democratic socialism" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 3 June 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Fiona Harvey (5 September 2014). "Green party to position itself as the real left of UK politics". The Guardian.

- Arnold, N. Scott (2009). Imposing values: an essay on liberalism and regulation. Florence: Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-495-50112-1.

Modern liberalism occupies the left-of-center in the traditional political spectrum and is represented by the Democratic Party in the United States, the Labor Party in the United Kingdom, and the mainstream Left (including some nominally socialist parties) in other advanced democratic societies.

- Clark, Barry (1998) Political Economy: A Comparative Approach. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Press ISBN 9780275958695

- "Home: Oxford English Dictionary". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Marshall, Peter (1993). Demanding the Impossible — A History of Anarchism. London: Fontana Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1.

- Van Gosse (2005). The Movements of the New Left, 1950–1975: A Brief History with Documents. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6804-3.

- Reuss, JoAnne C. (2000). American Folk Music and Left-Wing Politics. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-3684-6.

- "Steel to gop fight for Coleman". Time. 3 March 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- "Is it Spain's place to investigate Gitmo?". The Week. 7 May 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Reported in Mother Jones, 29 April 2009.

- Gellene, Denise (10 September 2007). "Study finds left-wing brain, right-wing brain". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Werckmeister, Otto Karl (1999). Icons of the Left: Benjamin and Eisenstein, Picasso and Kafka After the Fall of Communism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226893563.

- Gutman, David (1996). Prokofiev (New ed.). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0711920835.

- Andrew Glyn, Social Democracy in Neoliberal Times: The Left and Economic Policy since 1980, Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-19-924138-5.

- Beinhocker, Eric D. (2006). The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-1-57851-777-0.

- "The Neo-Marxian Schools". The New School. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 23 August 2007.

- Munro, John. "Some Basic Principles of Marxian Economics". University of Toronto. Retrieved 23 August 2007.

- "Lumpenproletariat". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "Communists: Marxism Fails on the Farm". Time. 13 October 1961. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Tom Mertes, A Movement of Movements, New York: Verso, 2004.

- Krishna-Hensel, Sai (2006). Global Cooperation: Challenges and Opportunities in the Twenty-first Century. Ashgate Publishing. p. 202.

- Juris, Jeffrey S. (2008). Networking Futures: The Movements against Corporate Globalization. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8223-4269-4.

- Paine, Thomas. "Agrarian Justice". Thomas Paine National Historical Association. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- Foster, J. B. (2000). Marx's Ecology. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Burkett, P. (1999). Marx and Nature. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312219406.

- "William Morris: The First Green Socialist". Leonora.fortunecity.co.uk. 14 December 2007. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- Moore, J. W. (2003). "Capitalism as World-ecology: Braudel and Marx on Environmental History" (PDF). Organization & Environment. 16 (4): 431–458. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.472.6464. doi:10.1177/1086026603259091. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2011.

- "Marx and ecology". Socialist Worker#United Kingdom. 8 December 2007. Archived from the original on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- Gare, A. (1996). "Soviet Environmentalism: The Path Not Taken". In Benton, E. (ed.). The Greening of Marxism. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 111–128. ISBN 978-1572301184.

- Kovel, J. (2002). The Enemy of Nature.

- Gare, Arran (2002). "The Environmental Record of the Soviet Union" (PDF). Capitalism Nature Socialism. 13 (3): 52–72. doi:10.1080/10455750208565489.

- Shapiro, Judith (2001). Mao's War against Nature: Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China. Cambridge University Press.

- Meredith Burgman, Green Bans, Red Union: Environmental Activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers' Federation, UNSW Press, Sydney, 1998.

- For example, see Wall, D., Babylon and Beyond: The Economics of Anti-Capitalist, Anti-Globalist and Radical Green Movements, 2005.

- Commoner, B., The Closing Circle, 1972.

- Sanra Ritten (19 October 2007). "Poor Bear Burden of Industrialisation" (PDF). Blacksmith Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- "Green Left homepage". Gptu.net. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- "President Evo Morales". The Daily Show. Comedy Central. 25 September 2007. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- James Hansen (31 December 2009). "How to Solve the Climate Problem". The Nation.

- Chomsky, Noam (1999). Profit Over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order (1st ed.). New York: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 9781888363821. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Trisha (6 August 2010). "The Nation: We Have Yet to See The Biggest Costs of the BP Spill". Raj Patel. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "Naomi Klein- Climate Debt (Part 1)". YouTube. 26 February 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "The Yes Men Fix the World :: Scrutiny Hooligans". Internet Archive. 27 July 2011. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Kucinich responds to BP Oil Spill". YouTube. 26 May 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "The Left Pushes Secular Religions: Global Warming, Embryonic Stem Cell Research – Michael Barone". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- "World Scientists' Warning To Humanity". Dieoff.org. 18 November 1992. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- Andrew C. Revkinnov (13 November 2007). "Global Warming – Books – The New York Times". New York Times. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

Challenges to both Left and Right on Global Warming", by Andrew C. Revkin, Nov. 13, 2007, "The right says global warming is somewhere between a hoax and a minor irritant, and argues that liberals' thirst for top-down regulations will drive American wealth to developing countries and turn off the fossil-fuelled engine powering the economy.

- "Weather Channel Founder Blasts Gore Over Global Warming Campaign". Fox News. 29 January 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- Mooney, Chris (2006). The Republican War on Science (Rev ed.). New York: BasicBooks. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-465-04676-8.

[T]he modern Right has adopted a style of politics that puts its adherents in increasingly stark conflict with both scientific information and dispassionate, expert analysis in general.

- "Rudd's carbon trading — locking in disaster". Green Left Weekly. 23 May 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "Carbon tax not the solution we need on climate". Solidarity Online. 10 March 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "James Hansen and climate solutions". Green Left Weekly. 13 March 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- Doyle, William (2002). The Oxford History of the French Revolution (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925298-5.

An exuberant, uncompromising nationalism lay behind France's revolutionary expansion in the 1790s...", "The message of the French Revolution was that the people are sovereign; and in the two centuries since it was first proclaimed it has conquered the world.

- Winock, Michel (dir.), Histoire de l'extrême droite en France (1993).

- Szporluk, Roman. Communism and Nationalism. 2nd. Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Solomos, John; Back, Les (1995). "Marxism, Racism, and Ethnicity" (PDF). American Behavioral Scientist. 38 (3): 407–420. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.602.5843. doi:10.1177/0002764295038003004.

- Lenin, Vladimir (1919). "Anti-Jewish Pogroms". Speeches On Gramophone Records.

- Perlman, Fredy (1985). The Continuing Appeal of Nationalism. Detroit: Black & Red. ISBN 978-0317295580.

- "What is Maioism-Third Worldism?". Anti-Imperialism.org. 2 November 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- Marx, Karl. 1976. Introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right. Collected Works, vol. 3. New York.

- Michael Burleigh, Sacred Causes HarperCollins (2006), p. 41–43.

- David van Biema, Jeff Chu (10 September 2006). "Does God Want You To Be Rich?". Time. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- James Brewer Stewrt, Abolitionist Politics and the Coming of the Civil War, University of Massachusetts Press, 2008, ISBN 978-1-55849-635-4. "[...] the progressive assumptions of 'uplift'." (page 40).

- "For Teachers (Library of Congress)". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- "Tony Cliff: Trotsky on substitutionism (Autumn 1960)". Marxists.org. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- "Against Substitutionism". Scribd.com. 6 November 2006. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- Campling, Valerie Bryson. Consultant ed.: Jo (2003). Feminist Political Theory: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire [u.a.]: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-94568-1.

- "Rosa Luxemburg: Women's Suffrage and Class Struggle (1912)". Marxists.org. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "Clara Zetkin: On a Bourgeois Feminist Petition". Marxists.org. 28 December 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "Clara Zetkin: Lenin on the Women's Question – 1". Marxists.org. 29 February 2004. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Alexandra Kollontai. "The Social Basis of the Woman Question by Alexandra Kollontai 1909". Marxists.org. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Alexandra Kollontai. "Women Workers Struggle For Their Rights by Alexandra Kollontai 1919". Marxists.org. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Alexandra Kollontai (26 August 1920). "1920-Inter Women's Day". Marxists.org. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- Cosseron, Serge (ed.). Le dictionnaire de l'extrême gauche. Paris: Larousse, 2007. p. 20.

- "Leftwing Extremists Increase in Cyber Attacks" (PDF). Archived from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "China launches 'New Deal' for farmers". Financial Times. 22 February 2006.

- "Benn's golden anniversary". BBC News. 4 December 2000. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- "MPs approve annual welfare cap in Commons vote". BBC News. 26 March 2014.

- John Kampfner (5 November 2012). "Labour's return to the right". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "International Socialism: Postmodernism, commodity fetishism and hegemony". Interet Archive. Archived from the original on 25 November 2005. Retrieved 3 June 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Noam Chomsky on Post-Modernism". Internet Archive. Archived from the original on 21 April 2003. Retrieved 3 June 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

Further reading

- Encyclopedia of the American Left, ed. by Mari Jo Buhle, Paul Buhle, Dan Georgakas, Second Edition, Oxford University Press 1998, ISBN 0-19-512088-4.

- Lin Chun, The British New Left, Edinburgh : Edinburgh Univ. Press, 1993.

- Geoff Eley, Forging Democracy: The History of the Left in Europe, 1850–2000, Oxford University Press 2002, ISBN 0-19-504479-7.

- "Leftism in India, 1917–1947", Satyabrata Rai Chowdhuri, Palgrave Macmillan, UK, 2007, ISBN 978-0-230-51716-5.

- Neither Washington Nor Stowe: Common Sense For The Working Vermonter, by David Van Deusen, Sean West, and the Green Mountain Anarchist Collective (NEFAC-VT), Catamount Tavern Press, 2004.

- The Rise and Fall of The Green Mountain Anarchist Collective, 2016.