Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich (Russian: ![]()

Shostakovich achieved fame in the Soviet Union under the patronage of Soviet chief of staff Mikhail Tukhachevsky, but later had a complex and difficult relationship with the government. Nevertheless, he received accolades and state awards and served in the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR (1947) and the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union (from 1962 until his death).

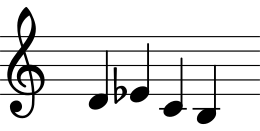

A polystylist, Shostakovich developed a hybrid voice, combining a variety of different musical techniques into his works. His music is characterized by sharp contrasts, elements of the grotesque, and ambivalent tonality; he was also heavily influenced by the neoclassical style pioneered by Igor Stravinsky, and (especially in his symphonies) by the late Romanticism of Gustav Mahler.

Shostakovich's orchestral works include 15 symphonies and six concerti. His chamber output includes 15 string quartets, a piano quintet, two piano trios, and two pieces for string octet. His solo piano works include two sonatas, an early set of preludes, and a later set of 24 preludes and fugues. Other works include three operas, several song cycles, ballets, and a substantial quantity of film music; especially well known is The Second Waltz, Op. 99, music to the film The First Echelon (1955–1956),[2] as well as the suites of music composed for The Gadfly.

Biography

Early life

Born at Podolskaya Street in Saint Petersburg, Russia, Shostakovich was the second of three children of Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich and Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina. Shostakovich's paternal grandfather, originally surnamed Szostakowicz, was of Polish Roman Catholic descent (his family roots trace to the region of the town of Vileyka in today's Belarus), but his immediate forebears came from Siberia.[3] A Polish revolutionary in the January Uprising of 1863–4, Bolesław Szostakowicz was exiled to Narym (near Tomsk) in 1866 in the crackdown that followed Dmitri Karakozov's assassination attempt on Tsar Alexander II.[4] When his term of exile ended, Szostakowicz decided to remain in Siberia. He eventually became a successful banker in Irkutsk and raised a large family. His son Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich, the composer's father, was born in exile in Narim in 1875 and studied physics and mathematics at Saint Petersburg University, graduating in 1899. He then went to work as an engineer under Dmitri Mendeleev at the Bureau of Weights and Measures in Saint Petersburg. In 1903 he married another Siberian transplant to the capital, Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina, one of six children born to a Russian Siberian native.[4]

Their son, Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, displayed significant musical talent after he began piano lessons with his mother at the age of nine. On several occasions he displayed a remarkable ability to remember what his mother had played at the previous lesson, and would get "caught in the act" of playing the previous lesson's music while pretending to read different music placed in front of him.[5] In 1918 he wrote a funeral march in memory of two leaders of the Kadet party murdered by Bolshevik sailors.[6]

In 1919, at age 13, Shostakovich was admitted to the Petrograd Conservatory, then headed by Alexander Glazunov, who monitored his progress closely and promoted him.[7] Shostakovich studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev after a year in the class of Elena Rozanova, composition with Maximilian Steinberg, and counterpoint and fugue with Nikolay Sokolov, with whom he became friends.[8] He also attended Alexander Ossovsky's music history classes.[9] Steinberg tried to guide Shostakovich on the path of the great Russian composers, but was disappointed to see him 'wasting' his talent and imitating Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Prokofiev. Shostakovich also suffered for his perceived lack of political zeal, and initially failed his exam in Marxist methodology in 1926. His first major musical achievement was the First Symphony (premiered 1926), written as his graduation piece at the age of 19. This work brought him to the attention of Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who helped Shostakovich find accommodation and work in Moscow, and sent a driver around in "a very stylish automobile" to take him to a concert.[10]

Early career

.jpg)

After graduation, Shostakovich initially embarked on a dual career as concert pianist and composer, but his dry playing style was often unappreciated (his American biographer, Laurel Fay, comments on his "emotional restraint" and "riveting rhythmic drive"). He won an "honorable mention" at the First International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw in 1927 and attributed the disappointing result to suffering from appendicitis and the jury being all Polish. He had his appendix removed in April 1927.[11] After the competition Shostakovich met the conductor Bruno Walter, who was so impressed by the composer's First Symphony that he conducted it at its Berlin premiere later that year. Leopold Stokowski was equally impressed and gave the work its U.S. premiere the following year in Philadelphia. Stokowski also made the work's first recording.[12][13]

Shostakovich concentrated on composition thereafter and soon limited his performances primarily to his own works. In 1927 he wrote his Second Symphony (subtitled To October), a patriotic piece with a pro-Soviet choral finale. Owing to its experimental nature, as with the subsequent Third Symphony, it was not critically acclaimed with the enthusiasm given to the First.[14]

1927 also marked the beginning of Shostakovich's relationship with Ivan Sollertinsky, who remained his closest friend until the latter's death in 1944. Sollertinsky introduced the composer to Mahler's music, which had a strong influence on Shostakovich from the Fourth Symphony onward.[15]

While writing the Second Symphony, Shostakovich also began work on his satirical opera The Nose, based on the story by Nikolai Gogol. In June 1929, against the composer's wishes, the opera was given a concert performance; it was ferociously attacked by the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM).[16] Its stage premiere on 18 January 1930 opened to generally poor reviews and widespread incomprehension among musicians.[17]

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Shostakovich worked at TRAM, a proletarian youth theatre. Although he did little work in this post, it shielded him from ideological attack. Much of this period was spent writing his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, which was first performed in 1934. It was immediately successful, on both popular and official levels. It was described as "the result of the general success of Socialist construction, of the correct policy of the Party", and as an opera that "could have been written only by a Soviet composer brought up in the best tradition of Soviet culture".[18]

Shostakovich married his first wife, Nina Varzar, in 1932. Difficulties led to a divorce in 1935, but the couple soon remarried when Nina became pregnant with their first child, Galina.[19]

First denunciation

On 17 January 1936, Joseph Stalin paid a rare visit to the opera for a performance of a new work, Quiet Flows the Don, based on the novel by Mikhail Sholokhov, by the little-known composer Ivan Dzerzhinsky, who was called to Stalin's box at the end of the performance and told that his work had "considerable ideological-political value".[20] On 26 January, Stalin revisited the opera, accompanied by Vyacheslav Molotov, Andrei Zhdanov and Anastas Mikoyan, to hear Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. He and his entourage left without speaking to anyone. Shostakovich had been forewarned by a friend that he should postpone a planned concert tour in Arkhangelsk in order to be present at that particular performance.[21] Eyewitness accounts testify that Shostakovich was "white as a sheet" when he went to take his bow after the third act.[22] In letters to Sollertinsky, Shostakovich recounted the horror with which he watched as Stalin shuddered every time the brass and percussion played too loudly. Equally horrifying was the way Stalin and his companions laughed at the lovemaking scene between Sergei and Katerina. The next day, Shostakovich left for Arkhangelsk, and was there when he heard on 28 January that Pravda had published a tirade titled Muddle Instead of Music, complaining that the opera was a "deliberately dissonant, muddled stream of sounds...[that] quacks, hoots, pants and gasps."[23] This was the signal for a nationwide campaign, during which even Soviet music critics who had praised the opera were forced to recant in print, saying they "failed to detect the shortcomings of Lady Macbeth as pointed out by Pravda".[24] There was resistance from those who admired Shostakovich, including Sollertinsky, who turned up at a composers' meeting in Leningrad called to denounce the opera and praised it instead. Two other speakers supported him. When Shostakovich returned to Leningrad, he had a telephone call from the commander of the Leningrad Military District, who had been asked by Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky to make sure that he was all right. When the writer Isaac Babel was under arrest four years later, he told his interrogators that "it was common ground for us to proclaim the genius of the slighted Shostakovich."[25]

On 6 February, Shostakovich was again attacked in Pravda, this time for his light comic ballet The Limpid Stream, which was denounced because "it jangles and expresses nothing" and did not give an accurate picture of peasant life on a collective farm.[26] Fearful that he was about to be arrested, Shostakovich secured an appointment with the Chairman of the USSR State Committee on Culture, Platon Kerzhentsev, who reported to Stalin and Molotov that he had instructed the composer to "reject formalist errors and in his art attain something that could be understood by the broad masses", and that Shostakovich had admitted being in the wrong and had asked for a meeting with Stalin, which was not granted.[27]

As a result of this campaign, commissions began to fall off, and Shostakovich's income fell by about three-quarters. His Fourth Symphony was due to receive its premiere on 11 December 1936, but he withdrew it from the public, possibly because it was banned, and the symphony was not performed until 1961. Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District was also suppressed. A bowdlerised version was eventually performed under a new title, Katerina Izmailova, on 8 January 1963. The anti-Shostakovich campaign also served as a signal to artists working in other fields, including art, architecture, the theatre and cinema, with the writer Mikhail Bulgakov, the director Sergei Eisenstein, and the theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold among the prominent targets. More widely, 1936 marked the beginning of the Great Terror, in which many of the composer's friends and relatives were imprisoned or killed. These included Tukhachevsky (shot months after his arrest); his brother-in-law Vsevolod Frederiks (a distinguished physicist, who was eventually released but died before he got home); his close friend Nikolai Zhilyayev (a musicologist who had taught Tukhachevsky; shot shortly after his arrest); his mother-in-law, the astronomer Sofiya Mikhaylovna Varzar (sent to a camp in Karaganda); his friend the Marxist writer Galina Serebryakova (20 years in camps); his uncle Maxim Kostrykin (died); and his colleagues Boris Kornilov and Adrian Piotrovsky (executed).[28] His only consolation in this period was the birth of his daughter Galina in 1936;[29] his son Maxim was born two years later.[30]

Withdrawal of the Fourth Symphony

The publication of the Pravda editorials coincided with the composition of Shostakovich's Fourth Symphony. The work marked a great shift in style, owing to the substantial influence of Mahler and a number of Western-style elements. The symphony gave Shostakovich compositional trouble, as he attempted to reform his style into a new idiom. He was well into the work when the Pravda article appeared. He continued to compose the symphony and planned a premiere at the end of 1936. Rehearsals began that December, but after a number of rehearsals, for reasons still debated today, decided to withdraw the symphony from the public. A number of his friends and colleagues, such as Isaak Glikman, have suggested that it was an official ban that Shostakovich was persuaded to present as a voluntary withdrawal.[31] Whatever the case, it seems possible that this action saved the composer's life: during this time Shostakovich feared for himself and his family. Yet he did not repudiate the work; it retained its designation as his Fourth Symphony. A piano reduction was published in 1946,[32] and the work was finally premiered in 1961, well after Stalin's death.[33]

During 1936 and 1937, in order to maintain as low a profile as possible between the Fourth and Fifth symphonies, Shostakovich mainly composed film music, a genre favored by Stalin and lacking in dangerous personal expression.[34]

Fifth Symphony and return to favor

The composer's response to his denunciation was the Fifth Symphony of 1937, which was musically more conservative than his earlier works. Premiered on 21 November 1937 in Leningrad, it was a phenomenal success. The Fifth brought many to tears and welling emotions.[35] Later, Shostakovich's purported memoir, Testimony, stated: "I'll never believe that a man who understood nothing could feel the Fifth Symphony. Of course they understood, they understood what was happening around them and they understood what the Fifth was about."[36]

The success put Shostakovich in good standing once again. Music critics and the authorities alike, including those who had earlier accused him of formalism, claimed that he had learned from his mistakes and become a true Soviet artist. In a newspaper article published under Shostakovich's name, the Fifth was characterized as "A Soviet artist's creative response to just criticism."[37] The composer Dmitry Kabalevsky, who had been among those who disassociated themselves from Shostakovich when the Pravda article was published, praised the Fifth and congratulated Shostakovich for "not having given in to the seductive temptations of his previous 'erroneous' ways."[38]

It was also at this time that Shostakovich composed the first of his string quartets. His chamber works allowed him to experiment and express ideas that would have been unacceptable in his more public symphonies. In September 1937 he began to teach composition at the Leningrad Conservatory, which provided some financial security.[39]

Second World War

In 1939, before Soviet forces attempted to invade Finland, the Party Secretary of Leningrad Andrei Zhdanov commissioned a celebratory piece from Shostakovich, the Suite on Finnish Themes, to be performed as the marching bands of the Red Army paraded through Helsinki. The Winter War was a bitter experience for the Red Army, the parade never happened, and Shostakovich never laid claim to the authorship of this work.[40] It was not performed until 2001.[41] After the outbreak of war between the Soviet Union and Germany in 1941, Shostakovich initially remained in Leningrad. He tried to enlist in the military but was turned away because of his poor eyesight. To compensate, he became a volunteer for the Leningrad Conservatory's firefighter brigade and delivered a radio broadcast to the Soviet people ![]()

His most famous wartime contribution was the Seventh Symphony. The composer wrote the first three movements in Leningrad and completed the work in Kuibyshev (now Samara), where he and his family had been evacuated. It remains unclear whether Shostakovich really conceived the idea of the symphony with the siege of Leningrad in mind. It was officially claimed as a representation of the people of Leningrad's brave resistance to the German invaders and an authentic piece of patriotic art at a time when morale needed boosting. The symphony was first premiered by the Bolshoi Theatre orchestra in Kuibyshev and was soon performed abroad in London and the United States. It was subsequently performed for broadcast in Leningrad while the city was still under siege. The orchestra had only 14 musicians left, so the conductor Karl Eliasberg had to recruit anyone who could play an instrument to perform.[43]

The family moved to Moscow in spring 1943. At the time of the Eighth Symphony's premiere, the tide had turned for the Red Army. As a consequence, the public, and most importantly the authorities, wanted another triumphant piece from the composer. Instead, they got the Eighth Symphony, perhaps the ultimate in sombre and violent expression in Shostakovich's output. In order to preserve Shostakovich's image (a vital bridge to the people of the Union and to the West), the government assigned the name "Stalingrad" to the symphony, giving it the appearance of mourning of the dead in the bloody Battle of Stalingrad. But the piece did not escape criticism. Its composer is reported to have said: "When the Eighth was performed, it was openly declared counter-revolutionary and anti-Soviet. They said, 'Why did Shostakovich write an optimistic symphony at the beginning of the war and a tragic one now? At the beginning, we were retreating and now we're attacking, destroying the Fascists. And Shostakovich is acting tragic, that means he's on the side of the fascists.'"[44] The work was unofficially but effectively banned until 1956.[45]

The Ninth Symphony (1945), in contrast, was much lighter in tone. Gavriil Popov wrote that it was "splendid in its joie de vivre, gaiety, brilliance, and pungency!"[46] But by 1946 it too was the subject of criticism. Israel Nestyev asked whether it was the right time for "a light and amusing interlude between Shostakovich's significant creations, a temporary rejection of great, serious problems for the sake of playful, filigree-trimmed trifles."[47] The New York World-Telegram of 27 July 1946 was similarly dismissive: "The Russian composer should not have expressed his feelings about the defeat of Nazism in such a childish manner". Shostakovich continued to compose chamber music, notably his Second Piano Trio (Op. 67), dedicated to the memory of Sollertinsky, with a bittersweet, Jewish-themed totentanz finale. In 1947, the composer was made a deputy to the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR.[48]

Second denunciation

In 1948, Shostakovich, along with many other composers, was again denounced for formalism in the Zhdanov decree. Andrei Zhdanov, Chairman of the RSFSR Supreme Soviet, accused the composers (including Sergei Prokofiev and Aram Khachaturian) of writing inappropriate and formalist music. This was part of an ongoing anti-formalism campaign intended to root out all Western compositional influence as well as any perceived "non-Russian" output. The conference resulted in the publication of the Central Committee's Decree "On V. Muradeli’s opera The Great Friendship," which targeted all Soviet composers and demanded that they write only "proletarian" music, or music for the masses. The accused composers, including Shostakovich, were summoned to make public apologies in front of the committee.[50][51] Most of Shostakovich's works were banned, and his family had privileges withdrawn. Yuri Lyubimov says that at this time "he waited for his arrest at night out on the landing by the lift, so that at least his family wouldn't be disturbed."[52]

The decree's consequences for composers were harsh. Shostakovich was among those dismissed from the Conservatory altogether. For him, the loss of money was perhaps the largest blow. Others still in the Conservatory experienced an atmosphere thick with suspicion. No one wanted his work to be understood as formalist, so many resorted to accusing their colleagues of writing or performing anti-proletarian music.[53]

In the next few years, Shostakovich composed three categories of work: film music to pay the rent, official works aimed at securing official rehabilitation, and serious works "for the desk drawer". The latter included the Violin Concerto No. 1 and the song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry. The cycle was written at a time when the postwar anti-Semitic campaign was already under way, with widespread arrests, including that of Dobrushin and Yiditsky, the compilers of the book from which Shostakovich took his texts.[54]

The restrictions on Shostakovich's music and living arrangements were eased in 1949, when Stalin decided that the Soviets needed to send artistic representatives to the Cultural and Scientific Congress for World Peace in New York City, and that Shostakovich should be among them. For Shostakovich, it was a humiliating experience, culminating in a New York press conference where he was expected to read a prepared speech. Nicolas Nabokov, who was present in the audience, witnessed Shostakovich starting to read "in a nervous and shaky voice" before he had to break off "and the speech was continued in English by a suave radio baritone".[55] Fully aware that Shostakovich was not free to speak his mind, Nabokov publicly asked him whether he supported the then recent denunciation of Stravinsky's music in the Soviet Union. A great admirer of Stravinsky who had been influenced by his music, Shostakovich had no alternative but to answer in the affirmative. Nabokov did not hesitate to write that this demonstrated that Shostakovich was "not a free man, but an obedient tool of his government."[56] Shostakovich never forgave Nabokov for this public humiliation.[57] That same year he was obliged to compose the cantata Song of the Forests, which praised Stalin as the "great gardener".[58]

Stalin's death in 1953 was the biggest step toward Shostakovich's rehabilitation as a creative artist, which was marked by his Tenth Symphony. It features a number of musical quotations and codes (notably the DSCH and Elmira motifs, Elmira Nazirova being a pianist and composer who had studied under Shostakovich in the year before his dismissal from the Moscow Conservatory),[59] the meaning of which is still debated, while the savage second movement, according to Testimony, is intended as a musical portrait of Stalin. The Tenth ranks alongside the Fifth and Seventh as one of Shostakovich's most popular works. 1953 also saw a stream of premieres of the "desk drawer" works.

During the forties and fifties, Shostakovich had close relationships with two of his pupils, Galina Ustvolskaya and Elmira Nazirova. In the background to all this remained Shostakovich's first, open marriage to Nina Varzar until her death in 1954. He taught Ustvolskaya from 1939 to 1941 and then from 1947 to 1948. The nature of their relationship is far from clear: Mstislav Rostropovich described it as "tender". Ustvolskaya rejected a proposal of marriage from him after Nina's death.[60] Shostakovich's daughter, Galina, recalled her father consulting her and Maxim about the possibility of Ustvolskaya becoming their stepmother.[61] Ustvolskaya's friend Viktor Suslin said that she had been "deeply disappointed" in Shostakovich by the time of her graduation in 1947 [source?]. The relationship with Nazirova seems to have been one-sided, expressed largely in his letters to her, and can be dated to around 1953 to 1956. He married his second wife, Komsomol activist Margarita Kainova, in 1956; the couple proved ill-matched, and divorced five years later.[62]

In 1954, Shostakovich wrote the Festive Overture, opus 96; it was used as the theme music for the 1980 Summer Olympics.[63] (His '"Theme from the film Pirogov, Opus 76a: Finale" was played as the cauldron was lit at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, Greece.)[64][65]

In 1959, Shostakovich appeared on stage in Moscow at the end of a concert performance of his Fifth Symphony, congratulating Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra for their performance (part of a concert tour of the Soviet Union). Later that year, Bernstein and the Philharmonic recorded the symphony in Boston for Columbia Records.[66][67]

Joining the Party

The year 1960 marked another turning point in Shostakovich's life: he joined the Communist Party. The government wanted to appoint him General Secretary of the Composers' Union, but in order to hold that position he was required to attain Party membership. It was understood that Nikita Khrushchev, the First Secretary of the Communist Party from 1953 to 1964, was looking for support from the intelligentsia's leading ranks in an effort to create a better relationship with the Soviet Union's artists.[68] This event has variously been interpreted as a show of commitment, a mark of cowardice, the result of political pressure, or his free decision. On the one hand, the apparat was undoubtedly less repressive than it had been before Stalin's death. On the other, his son recalled that the event reduced Shostakovich to tears,[69] and that he later told his wife Irina that he had been blackmailed.[70] Lev Lebedinsky has said that the composer was suicidal.[71] From 1962, he served as a delegate in the Supreme Soviet of the USSR.[72] Once he joined the Party, several articles he did not write denouncing individualism in music were published under his name in Pravda. By joining the party, Shostakovich also committed himself to finally writing the homage to Lenin that he had promised before. His Twelfth Symphony, which portrays the Bolshevik Revolution and was completed in 1961, was dedicated to Lenin and called "The Year 1917."[73] Around this time, his health began to deteriorate.

Shostakovich's musical response to these personal crises was the Eighth String Quartet, composed in only three days. He subtitled the piece "To the victims of fascism and war",[74] ostensibly in memory of the Dresden fire bombing that took place in 1945. Yet like the Tenth Symphony, the quartet incorporates quotations from several of his past works and his musical monogram. Shostakovich confessed to his friend Isaak Glikman, "I started thinking that if some day I die, nobody is likely to write a work in memory of me, so I had better write one myself."[75] Several of Shostakovich's colleagues, including Natalya Vovsi-Mikhoels[76] and the cellist Valentin Berlinsky,[77] were also aware of the Eighth Quartet's biographical intent. Peter J. Rabinowitz has also pointed to covert references to Richard Strauss's Metamorphosen in it.[78]

In 1962 Shostakovich married for the third time, to Irina Supinskaya. In a letter to Glikman, he wrote, "her only defect is that she is 27 years old. In all other respects she is splendid: clever, cheerful, straightforward and very likeable."[79] According to Galina Vishnevskaya, who knew the Shostakoviches well, this marriage was a very happy one: "It was with her that Dmitri Dmitriyevich finally came to know domestic peace... Surely, she prolonged his life by several years."[80] In November he made his only venture into conducting, conducting a couple of his own works in Gorky;[81] otherwise he declined to conduct, citing nerves and ill health.

That year saw Shostakovich again turn to the subject of anti-Semitism in his Thirteenth Symphony (subtitled Babi Yar). The symphony sets a number of poems by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, the first of which commemorates a massacre of Ukrainian Jews during the Second World War. Opinions are divided as to how great a risk this was: the poem had been published in Soviet media, and was not banned, but remained controversial. After the symphony's premiere, Yevtushenko was forced to add a stanza to his poem that said that Russians and Ukrainians had died alongside the Jews at Babi Yar.[82]

In 1965 Shostakovich raised his voice in defence of poet Joseph Brodsky, who was sentenced to five years of exile and hard labor. Shostakovich co-signed protests with Yevtushenko, fellow Soviet artists Kornei Chukovsky, Anna Akhmatova, Samuil Marshak, and the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. After the protests the sentence was commuted, and Brodsky returned to Leningrad.[83]

Later life, and death

In 1964 Shostakovich composed the music for the Russian film Hamlet, which was favourably reviewed by The New York Times: "But the lack of this aural stimulation—of Shakespeare's eloquent words—is recompensed in some measure by a splendid and stirring musical score by Dmitri Shostakovich. This has great dignity and depth, and at times an appropriate wildness or becoming levity".[84]

In later life, Shostakovich suffered from chronic ill health, but he resisted giving up cigarettes and vodka. Beginning in 1958 he suffered from a debilitating condition that particularly affected his right hand, eventually forcing him to give up piano playing; in 1965 it was diagnosed as poliomyelitis. He also suffered heart attacks the following year and again in 1971, and several falls in which he broke both his legs; in 1967 he wrote in a letter: "Target achieved so far: 75% (right leg broken, left leg broken, right hand defective). All I need to do now is wreck the left hand and then 100% of my extremities will be out of order."[85]

A preoccupation with his own mortality permeates Shostakovich's later works, such as the later quartets and the Fourteenth Symphony of 1969 (a song cycle based on a number of poems on the theme of death). This piece also finds Shostakovich at his most extreme with musical language, with 12-tone themes and dense polyphony throughout. He dedicated the Fourteenth to his close friend Benjamin Britten, who conducted its Western premiere at the 1970 Aldeburgh Festival. The Fifteenth Symphony of 1971 is, by contrast, melodic and retrospective in nature, quoting Wagner, Rossini and the composer's own Fourth Symphony.[86]

Shostakovich died of lung cancer on 9 August 1975. A civic funeral was held; he was interred in Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow.[87] Even before his death he had been commemorated with the naming of the Shostakovich Peninsula on Alexander Island, Antarctica.,[88] Despite suffering from Motor Neurone Disease (or ALS) from as early as the 1960s, Shostakovich insisted upon writing all his own correspondence and music himself, even when his right hand was virtually unusable.

He was survived by his third wife, Irina; his daughter, Galina; and his son, Maxim, a pianist and conductor who was the dedicatee and first performer of some of his father's works. Shostakovich himself left behind several recordings of his own piano works; other noted interpreters of his music include Emil Gilels, Mstislav Rostropovich, Tatiana Nikolayeva, Maria Yudina, David Oistrakh, and members of the Beethoven Quartet.

His last work was his Viola Sonata, which was first performed officially on 1 October 1975.[89]

Shostakovich's musical influence on later composers outside the former Soviet Union has been relatively slight, although Alfred Schnittke took up his eclecticism and his contrasts between the dynamic and the static, and some of André Previn's music shows clear links to Shostakovich's style of orchestration. His influence can also be seen in some Nordic composers, such as Lars-Erik Larsson.[90] Many of his Russian contemporaries, and his pupils at the Leningrad Conservatory were strongly influenced by his style (including German Okunev, Sergei Slonimsky, and Boris Tishchenko, whose 5th Symphony of 1978 is dedicated to Shostakovich's memory). Shostakovich's conservative idiom has grown increasingly popular with audiences both within and outside Russia, as the avant-garde has declined in influence and debate about his political views has developed.

Music

Overview

Shostakovich's works are broadly tonal and in the Romantic tradition, but with elements of atonality and chromaticism. In some of his later works (e.g., the Twelfth Quartet), he made use of tone rows. His output is dominated by his cycles of symphonies and string quartets, each totaling 15. The symphonies are distributed fairly evenly throughout his career, while the quartets are concentrated towards the latter part. Among the most popular are the Fifth and Seventh Symphonies and the Eighth and Fifteenth Quartets. Other works include the operas Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, The Nose and the unfinished The Gamblers, based on the comedy by Gogol; six concertos (two each for piano, violin and cello); two piano trios; and a large quantity of film music.

Shostakovich's music shows the influence of many of the composers he most admired: Bach in his fugues and passacaglias; Beethoven in the late quartets; Mahler in the symphonies; and Berg in his use of musical codes and quotations. Among Russian composers, he particularly admired Modest Mussorgsky, whose operas Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina he reorchestrated; Mussorgsky's influence is most prominent in the wintry scenes of Lady Macbeth and the Eleventh Symphony, as well as in satirical works such as "Rayok".[91] Prokofiev's influence is most apparent in the earlier piano works, such as the first sonata and first concerto.[92] The influence of Russian church and folk music is evident in his works for unaccompanied choir of the 1950s.[93]

Shostakovich's relationship with Stravinsky was profoundly ambivalent; as he wrote to Glikman, "Stravinsky the composer I worship. Stravinsky the thinker I despise."[94] He was particularly enamoured of the Symphony of Psalms, presenting a copy of his own piano version of it to Stravinsky when the latter visited the USSR in 1962. (The meeting of the two composers was not very successful; observers commented on Shostakovich's extreme nervousness and Stravinsky's "cruelty" to him.)[95]

Many commentators have noted the disjunction between the experimental works before the 1936 denunciation and the more conservative ones that followed; the composer told Flora Litvinova, "without 'Party guidance' ... I would have displayed more brilliance, used more sarcasm, I could have revealed my ideas openly instead of having to resort to camouflage."[96] Articles Shostakovich published in 1934 and 1935 cited Berg, Schoenberg, Krenek, Hindemith, "and especially Stravinsky" among his influences.[97] Key works of the earlier period are the First Symphony, which combined the academicism of the conservatory with his progressive inclinations; The Nose ("The most uncompromisingly modernist of all his stage-works"[98]); Lady Macbeth, which precipitated the denunciation; and the Fourth Symphony, described in Grove's Dictionary as "a colossal synthesis of Shostakovich's musical development to date".[99] The Fourth was also the first piece in which Mahler's influence came to the fore, prefiguring the route Shostakovich took to secure his rehabilitation, while he himself admitted that the preceding two were his least successful.[100]

In the years after 1936, Shostakovich's symphonic works were outwardly musically conservative, regardless of any subversive political content. During this time he turned increasingly to chamber works, a field that allowed him to explore different and often darker ideas without scrutiny.[101] While his chamber works were largely tonal, they gave Shostakovich an outlet for sombre reflection not welcomed in his more public works. This is most apparent in the late chamber works, which portray what Grove's Dictionary calls "world of purgatorial numbness";[102] in some of these he included tone rows, although he treated these as melodic themes rather than serially. Vocal works are also a prominent feature of his late output, setting texts often concerned with love, death and art.[103]

Jewish themes

Even before the Stalinist anti-Semitic campaigns in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Shostakovich showed an interest in Jewish themes. He was intrigued by Jewish music's "ability to build a jolly melody on sad intonations".[104] Examples of works that included Jewish themes are the Fourth String Quartet (1949), the First Violin Concerto (1948), and the Four Monologues on Pushkin Poems (1952), as well as the Piano Trio in E minor (1944). He was further inspired to write with Jewish themes when he examined Moisei Beregovski's 1944 thesis on Jewish folk music.[105]

In 1948, Shostakovich acquired a book of Jewish folk songs, from which he composed the song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry. He initially wrote eight songs meant to represent the hardships of being Jewish in the Soviet Union. To disguise this, he added three more meant to demonstrate the great life Jews had under the Soviet regime. Despite his efforts to hide the real meaning in the work, the Union of Composers refused to approve his music in 1949 under the pressure of the anti-Semitism that gripped the country. From Jewish Folk Poetry could not be performed until after Stalin's death in March 1953, along with all the other works that were forbidden.[106]

Self-quotations

Throughout his compositions, Shostakovich demonstrated a controlled use of musical quotation. This stylistic choice had been common among earlier composers, but Shostakovich developed it into a defining characteristic of his music. Rather than quoting other composers, Shostakovich preferred to quote himself. Musicologists such as Sofia Moshevich, Ian McDonald, and Stephen Harris have connected his works through their quotations.[107]

One example is the main theme of Katerina's aria, Seryozha, khoroshiy moy, from the fourth act of Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. It accompanies Katerina as she reunites with her lover Sergei. The aria's beauty comes as a breath of fresh air in the intense, overbearing tone of the scene. This goes well with the dialogue, as Katerina visits her lover in prison. The theme is made tragic when Sergei betrays her and finds a new lover upon blaming Katerina for his incarceration.[108]

More than 25 years later, Shostakovich quoted this theme in his eighth string quartet. In the midst of this quartet's oppressive and somber themes, the only light and cheerful moment is when the cello introduces the Seryozha theme about three minutes into the fourth movement. The quotation uses Katerina's hope amid misery as a means to demonstrate the hope of those oppressed by fascists.[109]

This theme emerges once again in his 14th string quartet. As in the eighth, the cello introduces the theme, but for an entirely different purpose. The last in Shostakovich's "quartet of quartets", the fourteenth serves to honor the cellist of the Beethoven String Quartet, Sergei Shirinsky. Rather than reflecting the original theme's intentions, the quotation serves as a dedication to Shirinsky.[110]

Posthumous publications

In 2004, the musicologist Olga Digonskaya discovered a trove of Shostakovich manuscripts at the Glinka State Central Museum of Musical Culture in Moscow. In a cardboard file were some "300 pages of musical sketches, pieces and scores" in Shostakovich's hand. "A composer friend bribed Shostakovich's housemaid to regularly deliver the contents of Shostakovich's office waste bin to him, instead of taking it to the garbage. Some of those cast-offs eventually found their way into the Glinka. ... The Glinka archive 'contained a huge number of pieces and compositions which were completely unknown or could be traced quite indirectly,' Digonskaya said."[111]

Among these were Shostakovich's piano and vocal sketches for a prologue to an opera, Orango (1932). They were orchestrated by the British composer Gerard McBurney and premiered in December 2011 by the Los Angeles Philharmonic.[111][112][113][114][115]

Criticism

According to McBurney, opinion is divided on whether Shostakovich's music is "of visionary power and originality, as some maintain, or, as others think, derivative, trashy, empty and second-hand".[116] William Walton, his British contemporary, described him as "the greatest composer of the 20th century".[117] Musicologist David Fanning concludes in Grove's Dictionary that "Amid the conflicting pressures of official requirements, the mass suffering of his fellow countrymen, and his personal ideals of humanitarian and public service, he succeeded in forging a musical language of colossal emotional power."[118]

Some modern composers have been critical. Pierre Boulez dismissed Shostakovich's music as "the second, or even third pressing of Mahler".[119] The Romanian composer and Webern disciple Philip Gershkovich called Shostakovich "a hack in a trance".[120] A related complaint is that Shostakovich's style is vulgar and strident: Stravinsky wrote of Lady Macbeth: "brutally hammering ... and monotonous".[121] English composer and musicologist Robin Holloway described his music as "battleship-grey in melody and harmony, factory-functional in structure; in content all rhetoric and coercion."[122]

In the 1980s, the Finnish conductor and composer Esa-Pekka Salonen was critical of Shostakovich and refused to conduct his music. For instance, he said in 1987:

Shostakovich is in many ways a polar counter-force for Stravinsky. [...] When I have said that the 7th symphony of Shostakovich is a dull and unpleasant composition, people have responded: "Yes, yes, but think of the background of that symphony." Such an attitude does no good to anyone.[123]

Salonen has since performed and recorded several of Shostakovich's works, including the Piano Concertos Nos. 1 and 2 (1999),[124] the Violin Concerto No. 1 (2010),[125] the Prologue to Orango and the Symphony No. 4 (2012).[126]

It is certainly true that Shostakovich borrows extensively from the material and styles both of earlier composers and of popular music; the vulgarity of "low" music is a notable influence on this "greatest of eclectics".[127] McBurney traces this to the avant-garde artistic circles of the early Soviet period in which Shostakovich moved early in his career, and argues that these borrowings were a deliberate technique to allow him to create "patterns of contrast, repetition, exaggeration" that gave his music large-scale structure.[128]

Personality

Shostakovich was in many ways an obsessive man: according to his daughter he was "obsessed with cleanliness".[129] He synchronised the clocks in his apartment and regularly sent himself cards to test how well the postal service was working. Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered indexes 26 references to his nervousness. Mikhail Druskin remembers that even as a young man the composer was "fragile and nervously agile".[130] Yuri Lyubimov comments, "The fact that he was more vulnerable and receptive than other people was no doubt an important feature of his genius."[131] In later life, Krzysztof Meyer recalled, "his face was a bag of tics and grimaces."[132]

In Shostakovich's lighter moods, sport was one of his main recreations, although he preferred spectating or umpiring to participating (he was a qualified football referee). His favourite football club was Zenit Leningrad (now Zenit Saint Petersburg), which he would watch regularly.[133] He also enjoyed card games, particularly patience.[89]

Shostakovich was fond of satirical writers such as Gogol, Chekhov and Mikhail Zoshchenko. Zoshchenko's influence in particular is evident in his letters, which include wry parodies of Soviet officialese. Zoshchenko noted the contradictions in the composer's character: "he is ... frail, fragile, withdrawn, an infinitely direct, pure child ... [but also] hard, acid, extremely intelligent, strong perhaps, despotic and not altogether good-natured (although cerebrally good-natured)."[134]

Shostakovich was diffident by nature: Flora Litvinova has said he was "completely incapable of saying 'No' to anybody."[135] This meant he was easily persuaded to sign official statements, including a denunciation of Andrei Sakharov in 1973.[136] His widow later told Helsingin Sanomat that his name was included without his permission.[137] But he was willing to try to help constituents in his capacities as chairman of the Composers' Union and Deputy to the Supreme Soviet. Oleg Prokofiev said, "he tried to help so many people that ... less and less attention was paid to his pleas."[138][136] When asked if he believed in God, Shostakovich said "No, and I am very sorry about it."[136]

Orthodoxy and revisionism

Shostakovich's response to official criticism and whether he used music as a kind of covert dissidence is a matter of dispute. He outwardly conformed to government policies and positions, reading speeches and putting his name to articles expressing the government line.[139] But it is evident he disliked many aspects of the regime, as confirmed by his family, his letters to Isaak Glikman, and the satirical cantata "Rayok", which ridiculed the "anti-formalist" campaign and was kept hidden until after his death.[140] He was a close friend of Marshal of the Soviet Union Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who was executed in 1937 during the Great Purge.[141]

It is also uncertain to what extent Shostakovich expressed his opposition to the state in his music. The revisionist view was put forth by Solomon Volkov in the 1979 book Testimony, which claimed to be Shostakovich's memoirs dictated to Volkov. The book alleged that many of the composer's works contained coded anti-government messages, placing Shostakovich in a tradition of Russian artists outwitting censorship that goes back at least to Alexander Pushkin. He incorporated many quotations and motifs in his work, most notably his musical signature DSCH.[142] His longtime musical collaborator Yevgeny Mravinsky said, "Shostakovich very often explained his intentions with very specific images and connotations."[143]

The revisionist perspective has subsequently been supported by his children, Maxim and Galina, although Maxim said in 1981 that Volkov's book was not his father's work.[144] Volkov has further argued, both in Testimony and in Shostakovich and Stalin, that Shostakovich adopted the role of the yurodivy or holy fool in his relations with the government. Other prominent revisionists are Ian MacDonald, whose book The New Shostakovich put forward further revisionist interpretations of his music, and Elizabeth Wilson, whose Shostakovich: A Life Remembered provides testimony from many of the composer's acquaintances.[145]

Musicians and scholars including Laurel Fay[146] and Richard Taruskin contest the authenticity and debate the significance of Testimony, alleging that Volkov compiled it from a combination of recycled articles, gossip, and possibly some information directly from the composer. Fay documents these allegations in her 2002 article 'Volkov's Testimony reconsidered',[147] showing that the only pages of the original Testimony manuscript that Shostakovich had signed and verified are word-for-word reproductions of earlier interviews he gave, none of which are controversial. Against this, Allan B. Ho and Dmitry Feofanov have pointed out that at least two of the signed pages contain controversial material: for instance, "on the first page of chapter 3, where [Shostakovich] notes that the plaque that reads 'In this house lived [Vsevolod] Meyerhold' should also say 'And in this house his wife was brutally murdered'."[148]

Recorded legacy

In May 1958, during a visit to Paris, Shostakovich recorded his two piano concertos with André Cluytens, as well as some short piano works. These were issued by EMI on an LP, reissued by Seraphim Records on LP, and eventually digitally remastered and released on CD. Shostakovich recorded the two concertos in stereo in Moscow for Melodiya. Shostakovich also played the piano solos in recordings of the Cello Sonata, Op. 40 with cellist Daniil Shafran and also with Mstislav Rostropovich; the Violin Sonata, Op. 134, with violinist David Oistrakh; and the Piano Trio, Op. 67 with violinist David Oistrakh and cellist Miloš Sádlo. There is also a short sound film of Shostakovich as soloist in a 1930s concert performance of the closing moments of his first piano concerto. A colour film of Shostakovich supervising one of his operas, from his last year, was also made.[149] A major achievement was EMI's recording of the original, unexpurgated opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. There was at least one recording of the cleaned-up version, Katerina Ismailova, that Shostakovich had made to satisfy Soviet censorship. But when conductor Mstislav Rostropovich and his wife, soprano Galina Vishnevskaya were finally allowed to emigrate to the West, the composer begged them to record the full original score, which they did in April 1978. It features Vishnevskaya as Katerina, Nicolai Gedda as Sergei, Dimiter Petkov as Boris Ismailov and a brilliant supporting cast under Rostropovich's direction.[150]

Awards

Belgium: Member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium (1960)[151]

Denmark: Léonie Sonning Music Prize (1973)[152]

Finland: Wihuri Sibelius Prize (1958)[153]

Soviet Union:

- Hero of Socialist Labor (1966)[154]

- Order of Lenin (1946, 1956, 1966)[155]

- Order of the October Revolution (1971)[156]

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1940)[157]

- People's Artist of the USSR (1954)[158]

- People's Artist of the RSFSR (1948)[48]

- International Peace Prize (1954)[158]

- Lenin Prize (1958 – for the 11th symphony "1905")[153]

- State Prize (1941 – for Piano Quintet; 1942 – for the 7th ("Leningrad") Symphony; 1946 – for Piano Trio no. 2; 1950 – for Song of the Forests; 1952 – for 10 poems for chorus)[159]

- Glinka State Prize of the RSFSR (1968 – for the poem "The Execution of Stepan Razin" for bass, chorus and orchestra)[160]

- Glinka State Prize of the RSFSR (1974 – for the 14th string quartet and choral cycle "Fidelity")[156]

United Kingdom: Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society (1966)[161]

See also

- Music written in all major and/or minor keys

- Sinyavsky–Daniel trial

- The Noise of Time – a novel concerning Shostakovich by English author Julian Barnes.

Notes

- Fay, Laurel; Fanning, David. "Shostakovich, Dmitry". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Pervyy eshelon on IMDb

- Fay (2000), p. 7.

- Wilson (2006), p. 4.

- Fay (2000), p. 9

- Fay (2000), p. 12

- Fay (2000), p. 17

- Fay (2000), p. 18

- Fairclough & Fanning (2008), p. 73

- McSmith, Andy (2015). Fear and the Muse Kept Watch, the Russian Masters – from Akhmativa and Pasternak to Shostakoviich and Eisenstein – under Stalin. New York: New Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-62097-079-9.

- The New Grove (2001).

- Hulme (2010), p. 19.

- Hulme (2010), p. 20.

- Meyer (1995), p. 143.

- Ivashkin (2016), p. 20.

- Wilson (2006), p. 84

- Wilson (2006), p. 85

- Shostakovich/Grigoryev & Platek (1981), p. 33.

- Fay (2000), p. 80

- McSmith, Andy. Fear and the Muse Kept Watch. p. 172.

- Classical Music (8 March 2004). "When opera was a matter of life or death". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Wilson (2006b), pp. 128–9.

- Fay, Laurel. Shostakovich. pp. 84–85.

- Downes, Olin. "Shostakovich Affair shows shift in point of view in the U.S.S.R.", The New York Times. 12 April 1936. p. X5.

- McSmith, Andy. Fear and the Muse Kept Watch. pp. 175–176.

- Wilson (2006), p. 130

- McSmith, Andy. Fear and the Muse Kept Watch. pp. 174–5.

- Wilson (2006), pp. 145–6

- Riley, John (2005). Dmitri Shostakovich: A Life in Film. I.B.Tauris. p. 32. ISBN 9781850434849.

- Charles, Eleanor (3 February 1985). "Shostakovich Orchestra Role". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Wilson (2006), pp. 143–4

- Hulme (2010), p. 167.

- Fay, Laurel E. (6 April 2003). "Music; Found: Shostakovich's Long-Lost Twin Brother". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Shostakovich/Volkov (1979), p. 59.

- Volkov (2004), p. 150.

- Shostakovich/Volkov (2000), p. 135.

- Taruskin (2009), p. 304.

- Wilson (2006), p. 152.

- Fay (2000), p. 97.

- Edwards (2006), p. 98.

- MTV3: Shostakovitshin kiistelty teos kantaesitettiin (in Finnish)

- Wilson (2006), p. 171.

- Blokker (1979), p. 31.

- Shostakovich/Volkov (2000), p.162.

- Wilson (2006), p. 203.

- Fay (2000): p. 147.

- Fay (2000): p. 152.

- Hulme (2010), p. xxiv.

- Shostakovich/Volkov (2004), p. 86.

- Blokker (1979), pp. 33–4.

- Wilson (2006), p. 241.

- Wilson (1994), p. 183.

- Wilson (1994), p. 252

- Wilson (2006), p. 269.

- Nabokov (1951), p. 204.

- Nabokov (1951), p. 205.

- Wilson (2006), p. 274.

- Knight, David B. (2006). Landscapes in Music: Space, Place, and Time in the World's Great Music. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 84. ISBN 9781461638599.

- Wilson (2006), p. 304.

- Fay (2000), p. 194.

- Fay (2000), p. 194; Wilson (2006), p. 297.

- Meyer (1995), p. 392.

- "1980 Summer Olympics Official Report from the Organizing Committee, vol. 2". p. 283. Archived from the original on 22 June 2006.

- "Lighting of the Cauldron | ATHENS 2004". YouTube. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "2004 Athens Opening Ceremony Music List". 30 August 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- OCLC 1114176116

- North, James H. (2006). New York Philharmonic: The Authorized Recordings, 1917–2005. Scarecrow Press. p. 117. ISBN 9780810862395.

- Wilson (1994), pp. 373–80.

- Ho & Feofanov (1998), p. 390.

- Manashir Yakubov, Programme notes for the 1998 Shostakovich seasons at the Barbican, London).

- Wilson (1994), p. 340.

- Hulme (2010), p. xxvii.

- MacDonald (2006), p. 247.

- Blokker (1979), 37.

- Letter dated 19 July 1960, reprinted in Glikman: pp. 90–91

- Wilson (2006), p. 263.

- Wilson (2006), p. 281.

- Rabinowitz, Peter J. (May 2007). "The Rhetoric of Reference; or, Shostakovich's Ghost Quartet". Narrative. 15 (2): 239–256. doi:10.1353/nar.2007.0013. JSTOR 30219253. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- Shostakovich/Glikman (2001), p. 102.

- Vishnevskaya (1985), p. 274.

- Wilson (2006), pp. 426–7.

- Sheldon, Richard (25 August 1985). "Neither Yevtushenko Nor Shostakovich Should Be Blamed". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Crump, Thomas (2014). Brezhnev and the Decline of the Soviet Union. New York: Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-315-88378-6.

- Crowther, Bosley, in New York Times, 15 September 1964.

- Shostakovich/Glikman (2001), p. 147.

- Service, Tom (23 September 2013). "Symphony guide: Shostakovich's 15th". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Dmitri Shostakovich Dead at 68 After Hospitalization in Moscow". The New York Times. 11 August 1975. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Shostakovich Peninsula USGS 01-JAN-75

- Wilson (2011)

- Musicweb International. Lars-Erik Larsson. Retrieved on 18 November 2005.

- Fay (2000), pp. 119, 165, 224.

- The New Grove (2001), pp. 288, 290.

- Green, Jonathan D. (1999). A Conductor's Guide to Choral-Orchestral Works, Twentieth Century, Part II. Scarecrow Press. p. 5. ISBN 081083376X.

- Shostakovich/Glikman (2001), p. 181.

- Wilson (1994), pp. 375–7.

- Wilson (1994), p. 426.

- Fay (2000), p. 88.

- The New Grove (2001), p. 289.

- The New Grove (2001), p. 290.

- Shostakovich/Glikman (2001), p. 315.

- See also The New Grove (2001), p. 294.

- The New Grove (2001), p. 300.

- Woodstra, Chris, ed. (2005). All Music Guide to Classical Music: The Definitive Guide to Classical Music. Backbeat Books. p. 1262. ISBN 0879308656.

- Wilson (1994), p. 268.

- Tentser (2014), p. 5.

- Wilson (1994), pp. 267–9.

- Sofia Moshevich, Dmitri Shostakovich, Pianist (Montréal: McGill-Queen's Press, 2004), 176. ISBN 0773525815, 9780773525818; see next paragraphs for more.

- Ian MacDonald, The New Shostakovich (London: Fourth Estate, 1990), 88. ISBN 1872180418, 9781872180410

- Harris, Stephen (9 April 2016). "Quartet No. 8". Shostakovich: The String Quartets. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Harris, Stephen (24 August 2015). "Quartet No. 14". Shostakovich: The String Quartets. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Loiko, Sergei L.; Johnson, Reed (27 November 2011). "Shostakovich's 'Orango' found, finished, set for Disney Hall". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- Ayala, Ted (7 December 2011). "No Monkey Business with LAPO's World Premiere of Shostakovich's 'Orango'". Crescenta Valley Weekly. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Sirén, Vesa (6 April 2009). "Šostakovitšin apinaooppera löytyi" [The ape opera by Shostakovich was found]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Helsinki: Sanoma Oy. pp. C1. Archived from the original on 8 April 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- "Unknown Shostakovich Opera Discovered". Artsjournal. 21 March 2009. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2009 – via Le Devoir.

- Philadelphia Orchestra program, 27 October 2011

- McBurney (2002), p. 283.

- British Composers in Interview by R Murray Schafer (Faber 1960).

- The New Grove (2001), p. 280.

- McBurney (2002), p. 288.

- McBurney (2002), p. 290.

- McBurney (2002), p. 286.

- Holloway, Robin (26 August 2000). "Shostakovich horrors". The Spectator: 41. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Salonen, Esa-Pekka & Otonkoski, Lauri: Kirja – puhetta musiikitta, p. 73. Helsinki: Tammi. ISBN 951-30-6599-5

- OCLC 920558136

- Brown, Ismene (17 August 2011). "BBC Proms: Batiashvili, Philharmonia Orchestra, Salonen". theartsdesk.com. Esher: The Arts Desk Ltd. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- OCLC 809867885

- Haas, Shostakovich's Eighth: C minor Symphony against the Grain p. 125.

- McBurney (2002), p. 295.

- Michael Ardov,Memories of Shostakovich p. 139.

- Wilson (1994), pp. 41–5.

- Wilson (1994), p. 183.

- Wilson (1994), p. 462.

- Mentioned in his personal correspondence (Shostakovich, tr. Phillips (2001)), as well as other sources.

- Quoted in Fay (2000), p. 121.

- Wilson (1994), p. 162.

- Fay (2000), p. 263.

- Vesa Sirén: "Mitä setämies sai sanoa Neuvostoliitossa?" in Helsingin Sanomat on page A 6, 2 November 2018

- Wilson (1994), p. 40.

- Wilson (2006), pp. 369–70.

- Wilson (2006), p. 336.

- Mc Granahan, William J. (1978). "The Fall and Rise of Marshal Tukhachevsky" (PDF). Parameters, Journal of the US Army War College. VIII (4): 63.

- This appears in several of his works, including the Pushkin Monologues, Symphony No. 10, and String Quartets Nos 5, 8 & 11.

- Wilson (1994), p. 139.

- "Shostakovich's son says moves against artists led to defection". The New York Times. New York. 14 May 1981. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

Asked about the authenticity of a book published in the West after his father's death, and described as his memoirs, Mr. Shostakovich replied: These are not my father's memoirs. This is a book by Solomon Volkov. Mr. Volkov should reveal how the book was written. Mr. Shostakovich said language in the book attributed to his father, as well as several contradictions and inaccuracies, led him to doubt the book's authenticity.

- Gerstel, Jennifer (1999). "Irony, Deception, and Political Culture in the Works of Dmitri Shostakovich". Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal. University of Manitoba. 32 (4): 38. JSTOR 44029848.

- Fay (2000), p. 4. "Whether Testimony faithfully reproduces Shostakovich's confidences ... in a form and context he would have recognized and approved for publication remains doubtful. Yet even were [its] claim to authenticity not in doubt, it would still furnish a poor source for the serious biographer."

- Fay (2002).

- Ho & Feofanov (1998), p. 211.

- "Dmitri Shostakovich filmed in 1975 during rehearsals". YouTube. 9 January 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- OCLC 42448562

- Index biographique des membres et associés de l'Académie royale de Belgique (1769–2005). (in French)

- "Léonie Sonning Prize 1973 Dmitri Sjostakovitj". sonningmusic.org. The Léonie Sonning Music Foundation. 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Hulme (2010), p. xxvi.

- Shostakovich: A Life, Laurel E. Fay, p. 249

- Shostakovich: A Life, Laurel E. Fay, pp. 153; 198; 249

- Hulme (2010), p. xxix.

- Hulme (2010), p. xxii.

- Hulme (2010), p. xxv.

- Hulme (2010), pp. xxiii–xxv.

- Hulme (2010), p. xxviii.

- Dmitry Shostakovich at the Encyclopædia Britannica

References

- Ardov, Michael (2004). Memories of Shostakovich. Short Books. ISBN 978-1-904095-64-4.

- Blokker, Roy (1979). The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich, the Symphonies. The great composers. Associated Univ Press. ISBN 978-083861948-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwards, Robert (2006). White Death: Russia's War on Finland 1939–40. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84630-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fairclough, Pauline; Fanning, David, eds. (November 2008). The Cambridge Companion to Shostakovich. Cambridge Companions to Music (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521603157.

- Fanning, David; Fay, Laurel (2001). "Dmitri Shostakovich". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). Macmillan.

- Fay, Laurel (2000). Shostakovich: A Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513438-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fay, Laurel (2002). "Volkov's Testimony Reconsidered". In Hamrick Brown, Malcolm (ed.). A Shostakovich Casebook. Indiana University Press. pp. 22–66. ISBN 978-0-253-21823-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haas, David. "Shostakovich's Eighth: C minor Symphony against the Grain". In Bartlett, Rosamund (ed.). Shostakovich in Context.

- Ho, Allan; Feofanov, Dmitry (1998). Shostakovich Reconsidered. Toccata Press. ISBN 978-0-907689-56-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hulme, Derek C. (2010) [2002]. Dmitri Shostakovich Catalogue: The First Hundred Years and Beyond (4th ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7264-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ivashkin, Alexander (2016). "Shostakovich, Old Believers and New Minimalists". In Kirkman, Andrew; Ivashkin, Alexander (eds.). Contemplating Shostakovich: Life, Music and Film. Routledge. ISBN 9781317161028.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kovnatskaya, Liudmila, ed. (1996). D. D. Shostakovich: Collections to the 90th anniversary. St Petersburg: Kompozitor.

- Kovnatskaya, Liudmila, ed. (2000). D. D. Shostakovich: Between the moment and Eternity. Documents. Articles. Publications. St Petersburg: Kompozitor.

- MacDonald, Ian (2006) [1990]. The New Shostakovich. Pimlico. ISBN 978-184595064-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacDonald, Ian. "Shostakovichiana". Music Under Soviet Rule. Retrieved 17 August 2005.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McBurney, Gerard (2002). "Whose Shostakovich?". In Hamrick Brown, Malcolm (ed.). A Shostakovich Casebook. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21823-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meyer, Krzysztof (1995). Schostakowitsch – Sein Leben, sein Werk, seine Zeit (in German). Bergisch Gladbach: Gustav Lübbe Verlag. ISBN 978-3785707722. [Orig. in Polish 1973.]CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nabokov, Nicolas (1951). Old Friends and New Music. Hamish Hamilton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- van Rijen, Onno. "Opus by Shostakovich". Shostakovich & Other Soviet Composers. Archived from the original on 5 September 2005. Retrieved 17 August 2005.

- Sheinberg, Esti (29 December 2000). Irony, satire, parody and the grotesque in the music of Shostakovich. UK: Ashgate. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-7546-0226-2.

- Shostakovich, Dmitri (1981). Shostakovich: About Himself and His Times. Compiled by L. Grigoryev and Y.. Platek. Translated by Angus and Neilian Roxburgh. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- Shostakovich, Dmitri. Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich. Compiled and edited by Solomon Volkov:

- - (1st ed.). Faber and Faber. 1979. ISBN 978-0-571-11829-8.

- - (7th ed.). Proscenium. 2000. ISBN 978-0-87910-021-6.

- - (25th ed.). Hal Leonard. 2004. ISBN 978-161774771-7.

- Shostakovich, Dmitri; Glikman, Isaak (2001). Story of a Friendship: The Letters of Dmitry Shostakovich to Isaak Glikman. Translated by Phillips, Anthony. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3979-7.

- Tentser, Alexander (2014). "Dmitri Shostakovich and Jewish Music: The Voice of an Oppressed People". In Tentser, Alexander (ed.). The Jewish Experience in Classical Music: Shostakovich and Asia. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-5467-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taruskin, Richard (2009). On Russian Music. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24979-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vishnevskaya, Galina (1985). Galina, A Russian Story. Translated by Guy Daniels (1st ed.). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0156343206.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Volkov, Solomon (2004). Shostakovich and Stalin: The Extraordinary Relationship Between the Great Composer and the Brutal Dictator. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41082-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Elizabeth. Shostakovich: A Life Remembered:

- - (1st ed.). Princeton University Press. 1994. ISBN 978-069102971-9.

- - (2nd ed.). Faber and Faber. 2006. ISBN 978-057122050-2.

- - (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. 2006b. ISBN 978-0691128863.

- - (2nd ed. - Kindle) Faber and Faber. 2010. ISBN 978-057126115-4.

- - (New ed.). Faber and Faber. 2011. ISBN 9780571261154.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dmitri Shostakovich |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dmitri Shostakovich. |

- Dmitry Shostakovich at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Complete catalogue of works, with many additional comments by Sikorski

- The Shostakovich Debate: Interpreting the composer's life and music

- One Resurrected Drunkard: A Dialogue on Tony Palmer's Testimony Article on Palmer's Shostakovich film in Bright Lights Film Journal

- Dmitry Shostakovich about Iosif Andriasov

- Journey of Dmitri Shostakovich – an interview with filmmaker Helga Landauer

- Epitonic.com: Dimitri Shostakovich featuring tracks from Written with the Heart's Blood

- Video of Shostakovich on YouTube, at a rehearsal of his opera The Nose in 1975

- "Discovering Shostakovich". BBC Radio 3.

- BBC Presenter Stephen Johnson on Shostakovich and Depression

- Altovaya sonata. Dmitriy Shostakovich (1981) (Sonata for Viola), documentary film on Shostakovich's life, and difficulties with Khrennikov and Stalin

- Complete opus list, comprehensive discography, bibliography, filmography, list of first performances and links by Yosuke Kudo

- Archive of BBC's "Discovering Music" radio show, featuring Shostakovich's Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 10, String Quartet No. 8, and Cello Concerto No. 1.

- Various pieces by Shostakovich in streaming media by Classical Music Archives

- Shostakovich: the 24 preludes Op. 34

- University of Houston Moderated Discussion List: Dmitri Shostakovich and other Russian Composers

- Shostakovich: the string quartets

- Shostakovich: the quartets in context

- Interview with the composer's son, conductor Maxim Shostakovich by Bruce Duffie, 10 July 1992

- Paterson, Harry (21 December 2000). "Shostakovich: Revolutionary life, revolutionary legacy". Weekly Worker. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- "Shostakovich's Tenth Symphony: The Azerbaijani Link – Elmira Nazirova" by Aida Huseinova, in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 11:1 (Spring 2003), pp. 54–59.

- Ho, Allan B.; Feofanov, Dmitry (2011). "The Shostakovich Wars" (PDF). Southern Illinois University – Edwardsville. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- Dmitri Shostakovich on IMDb