Centre-left politics

Centre-left politics (British English) or center-left politics (American English), also referred to as moderate-left politics, are political views that lean to the left-wing on the left–right political spectrum, but closer to the centre than other left-wing politics. Those on the centre-left believe in working within the established systems to improve social justice.[1] The centre-left promotes a degree of social equality that it believes is achievable through promoting equal opportunity.[2] The centre-left has promoted luck egalitarianism, which emphasizes the achievement of equality requires personal responsibility in areas in control by the individual person through their abilities and talents as well as social responsibility in areas outside control by the person in their abilities or talents.[3]

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||

| Party politics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political spectrum | ||||||

|

||||||

| Party platform | ||||||

| Party organization | ||||||

|

||||||

| Party system | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Coalition | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Lists | ||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||

The centre-left opposes a wide gap between the rich and the poor and supports moderate measures to reduce the economic gap, such as a progressive income tax, laws prohibiting child labour, minimum wage laws, laws regulating working conditions, limits on working hours and laws to ensure the workers' right to organize.[2] The centre-left typically claims that complete equality of outcome is not possible, but instead that equal opportunity improves a degree of equality of outcome in society.[2]

In Europe, the centre-left includes social democrats, progressives and also some democratic socialists, greens and the Christian left. Some social liberals are described as centre-left, but many social liberals are in the centre of the political spectrum as well.[4][5]

Positions associated with the centre-left

The main ideologies of the centre-left are social democracy, social liberalism (sometimes, when paired with other ideologies; can also be considered centrist), progressivism, democratic socialism (moderate forms) and green politics (also can take place under a red–green alliance when cooperating with other parties on the left).

Throughout the world, centre-left groups generally support:

- A mixed economy consisting of both publicly owned or subsidized programmes of education, universal health care, child care and related social services for all citizens.

- A system of social security, with the stated goal of counteracting the effects of poverty and insuring the general public against loss of income following illness, unemployment or retirement (national Insurance contributions)

- Government bodies that regulate private enterprise in the interests of workers and consumers by ensuring labour rights (eg. supporting worker access to trade unions, workers participation, consumer protections and fair market competition).

- A system of progressive taxation that includes tax breaks and subsidies for those under poverty extended from government.

- A value-added tax (or occasionally a wealth tax) to fund government expenditures.

- Government investments and spending, for example in public works, and Keynesian economics.

The term may be used to imply positions on the environment, religion, public morality, etc., but these are usually not the defining characteristics, since centre-right parties may sometimes take similar positions on these issues.[6] A centre-left party may or may not be more concerned with reducing industrial emissions than a centre-right party[7][8] if not explicitly adhering to a green ideology.

History

The term "centre-left" appeared during the French "July Monarchy" in 1830s,[9] a political-historical phase during the Kingdom of France when the House of Orléans reigned under an almost parliamentary system. The centre-left was distinct from the left, composed of republicans, as well as the centre-right, composed of the Third Party and the liberal-conservative Doctrinaires.

During this time, the centre-left was led by Adolphe Thiers (head of the liberal-nationalist Movement Party) and Odilon Barrot, who headed the populist "Dynastic Opposition".[10] The centre-left was Orléanist, but supported a liberal interpretation of the Charter of 1830, more power to the Parliament, manhood suffrage and support to rising European nationalisms. Adolphe Thiers served as Prime Minister for King Louis Philippe I twice (in 1836 and 1840), but he then lost the King's favour, and the centre-left rapidly fell.[11]

In France, during the Second Republic and the Second Empire the centre-left was not strong or organised, but became commonly associated with the moderate republicans' group in Parliament. Finally, in 1871 the Second Empire fell as consequence of the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and Adolphe Thiers re-established the centre-left after the foundation of the Third Republic. This time the centre-left was constituted of moderate republicans, then called "Opportunists", anti-royalist liberals and radicals from the Republican Union. During the Third Republic, the centre-left was led by political and intellectual figures like Jules Dufaure, Édouard René de Laboulaye, Charles de Rémusat, Léon Say, William Waddington, Jean Casimir-Perier, Edmond Henri Adolphe Schérer and Georges Picot.[12]

Elsewhere in Europe, centre-left movements appeared from the 1860s, mainly in Spain and Italy. In Italy, the centre-left was born as coalition between the liberal Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour and the progressive Urbano Rattazzi, the heads respectively of the Right and Left groupings in Parliament. This alliance was called "connubio" ("marriage") for its opportunist characteristics.[13] In the 1900s, centre-left positions were expressed by people and parties who believed in social democracy and democratic socialism, but also some liberals or Christian-democrats were associated with the centre-left. Currently, the centre-left parties in Europe are united in the social democratic Party of European Socialists and ecologist European Green Party.

Despite the rise of centre-left politics in continental Europe, Britain and its colonies, along with the United States, only saw the rise of the centre-left in the late 19th century to the early 20th century. The prevalence of the position occurred mainly due to the rise of socialism caused Liberals to move away from laissez-faire policies to more interventionist policies, which created the New Liberal movement.

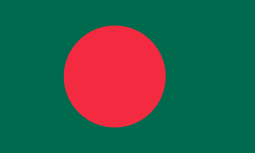

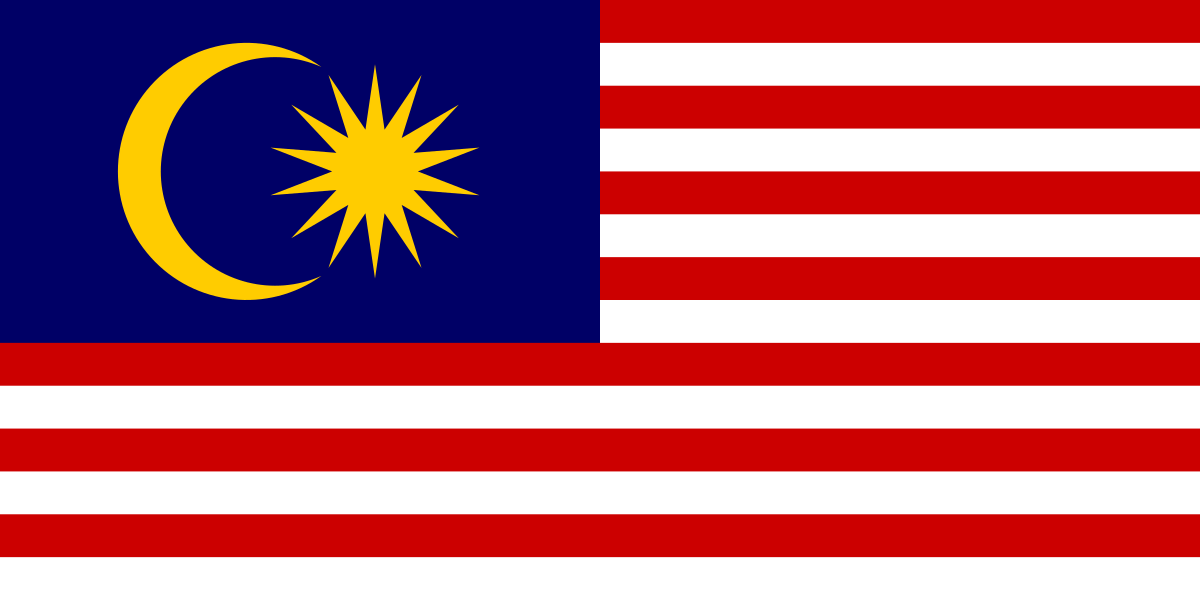

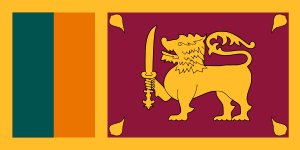

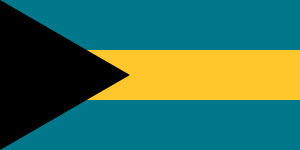

List of major centre-left parties

Current major centre-left parties within the anglosphere include the following:

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

See also

References

- Oliver H. Woshinsky. Explaining Politics: Culture, Institutions, and Political Behavior. New York: Routledge, 2008, pp. 146.

- Oliver H. Woshinsky. Explaining Politics: Culture, Institutions, and Political Behavior. New York: Routledge, 2008, pp. 143.

- Chris Armstrong. Rethinking Equality: The Challenge of Equal Citizenship. Manchester University Press, 2006, p. 89.

- John W. Cioffi and Martin Höpner (21 April 2006). "Interests, Preferences, and Center-Left Party Politics in Corporate Governance Reform" (PDF). Council for European Studies at Columbia University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- Manfred Ertel, Hans-Jürgen Schlamp and Stefan Simons (24 September 2009). "The Credibility Trap – Europe's Center-Left Parties Stuck in a Dead End". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- John Lloyd (2 October 2009). "Europe's centre-left suffers in the squeezed middle". Financial Times. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- "Spotlight on pollution and the environment". Workers Power. 8 May 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- Tierra Curry (6 November 2009). "Dirty Coal Czar Confirmed by Senate". Center for Biological Diversity. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- Paul W. Schroeder (1996). The Transformation of European Politics, 1763-1848. Claredon. p. 742.

- Michael Drolet (11 August 2003). Tocqueville, Democracy and Social Reform. Springer. p. 14.

- Alice Primi; Sophie Kerignard; Véronique Fau-Vincenti (2004). 100 fiches d'histoire du XIXe siècle. Bréal.

- Unknown (1993). Léon Say et le centre gauche: 1871-1896 : la grande bourgeoisie libérale dans les débuts de la Troisième République. p. 196.

- Serge Berstein; Pierre Milza (1992). Histoire de l'Europe contemporaine: le XIXe siècle (1815-1919). Hatier.

External links

- "Leftist parties of the world". Nico Biver. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2009.