Religion in Romania

Romania is a secular state, and it has no state religion. Romania is the most religious out of 34 European countries.[1] and a majority of the country's citizens are Christian. The Romanian state officially recognizes 18 religions and denominations.[2] 81.04% of the country's stable population identified as part of the Eastern Orthodox Church in the 2011 census (see also: History of Christianity in Romania). Other Christian denominations include the Catholic Church (both Latin Catholicism (4.33%) and Greek Catholicism (0.75%–3.3%), Calvinism (2.99%), and Pentecostal denominations (1.80%). This amounts to approximately 92% of the population identifying as Christian. Romania also has a small but historically significant Muslim minority, concentrated in Northern Dobruja, who are mostly of Crimean Tatar and Turkish ethnicity and number around 44,000 people. According to the 2011 census data, there are also approximately 3,500 Jews, around 21,000 atheists and about 19,000 people not identifying with any religion. The 2011 census numbers are based on a stable population of 20,121,641 people and exclude a portion of about 6% due to unavailable data.[3]

Religious denominations in Romania according to the 2011 census, given as percentages of the total stable population.

Religious denominations

Eastern Orthodoxy

The Eastern Orthodox Church is the largest religious denomination in Romania, numbering 16,307,004 according to the 2011 census, or 81.04% of the population. The rate of church attendance is, however, significantly lower. According to a poll conducted by INSCOP in July 2015, 37.8% of Romanians who declare themselves to be religious go to church only on major holidays, 25.4% once a week (especially on Sunday), 18.9% once a month, 10.2% once a year or less, 3.4% say they do not go to church, 2.7% a few times a week, and only 0.9% say they go to church daily.[4]

Roman Catholic Church (Latin Rite)

.jpg)

According to the 2011 census, there are 870,774 Catholics belonging to the Latin Church in Romania, making up 4.33% of the population. The largest ethnic groups are Hungarians (500,444, including Székelys; 41% of the Hungarians), Romanians (297,246 or 1.8%), Germans (21,324 or 59%), and Roma (20,821 or 3.3%), as well as a majority of the country's Slovaks, Bulgarians, Croats, Italians, Czechs, Poles, and Csangos (27,296 in all).

Greek Catholic Church (Byzantine Rite)

According to the 2011 census, there are 150,593 Greek Catholics in Romania, making up 0.75% of the population. The majority of Greek Catholics live in the northern part of Transylvania. Most are Romanians (124,563), with the remainder mostly Hungarians or Roma.

On the other hand, according to data published in the 2012 Annuario Pontificio, the Romanian Greek Catholic Church had 663,807 members (3.3% of the total population), 8 bishops, 1,250 parishes, some 791 diocesan priests and 235 seminarians of its own rite at the end of 2012.[5] The dispute over the figure is included in the United States Department of State report on religious freedom in Romania.[6] The Romanian Orthodox Church continues to claim many of the Romanian Greek Catholic Church's properties.[7]

Protestantism

According to the 2011 census, Protestants make up 6.2% of the total population. They have been historically been made up of Lutherans, Calvinists and Unitarians, although in recent years Evangelical Protestants, Pentecostals and newer Protestant groups spread and are holding a greater share. In 1930, prior to World War II, they constituted approximately 8.8% of the Romanian population. The largest denominations included in this figure (6.2%) are the Reformed (2.99%) and the Pentecostals (1.8%). Others also included are Baptists (0.56%), Seventh-day Adventists (0.4%), Unitarians (0.29%), Plymouth Brethren (0.16%) and two Lutheran churches (0.13%), the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Romania (0.1%) and the Evangelical Church of Augustan Confession in Romania (0.03%). Of these various Protestant groups, Hungarians account for most of the Reformed, Unitarians, and Evangelical Lutherans; Romanians are the majority of the Pentecostals, Baptists, Seventh-day Adventists and Evangelical Christians; while Germans account for most of the Augustan Confession Evangelicals (i.e. Lutherans historically subscribing to the Augsburg Confession). The majority of Calvinist (Reformed Church) and Unitarians have their services in Hungarian.

Not to be confused with any of the above is the Evangelical Church of Romania (0.08%), an unrelated Protestant denomination.

Islam

Although the number of adherents of Islam is relatively small, Islam enjoys a 700-year tradition in Romania particularly in Northern Dobruja,[8] a region on the Black Sea coast which was part of the Ottoman Empire for almost five centuries (ca. 1420–1878).[9] According to the 2011 census, 64,337 people, approx. 0.3% of the total population, indicated that their religion was Islam. The majority of the Romanian Muslims belong to the Sunni Islam.

97% of the Romanian Muslims are residents of the two counties forming Northern Dobruja: eighty-five percent live in Constanța County, and twelve percent in Tulcea County.[8] The remaining Muslims live in cities like Bucharest, Brăila, Călărași, Galați, Giurgiu, Drobeta-Turnu Severin.[8] Ethnically, most of them are Tatars, followed by Turks, Albanians, Muslim Roma, and immigrants from the Middle East and Africa.[8][10] Since 2007, there are Indonesian, Bangladeshi and Pakistani workers coming to Romania, who are mostly Muslims.

In Romania there are about 80 mosques.[11] One of the largest is the Grand Mosque of Constanța, originally known as the Carol I Mosque. It was built between 1910 and 1913, on the order of Carol I, in appreciation for the Muslim community in Constanța. According to the legal status of the Muslim denomination, the Romanian Muslim community is officially represented by a mufti, while the Muftiat is the denominational and cultural representative institution of the Muslim community,[12] with a status similar with that of the other denominations officially recognized by the Romanian state.[13] Likewise, Muslims in Constanța, which comprise approx. 6% of the population of this county, are represented in the Parliament by the Democratic Union of Turkish-Muslim Tatars of Romania, founded on 29 December 1989.[14]

Judaism

In 1930, more than 700,000 people in the Kingdom of Romania (including Bessarabia) practiced Judaism. By 2011, that number had dropped to 3,271. A legacy of the country's once numerous Jewish congregations is the large number of synagogues throughout Romania. Today, between 200,000 and 400,000 descendants of Romanian Jews are living in Israel.

Other religions

Other denominations not listed above but recognised as official religions by the Romanian state are listed here. The Jehovah's Witnesses number around 50,000 adherents (0.25% of the stable population). Old Believers make up about 0.16% of the population with 30,000 adherents, who are mainly ethnic Russians living in the Danube Delta region. Serbian Orthodox believers are present in the areas which border Serbia and number about 14,000 people. Once fairly well represented in Romania, Judaism has fallen to around 3,500 adherents in 2011, which is about 0.02% of the population. Less still is the Armenian Christian minority, numbering about 400 people in total. The Association of Religion Data Archives reports 1,869 Bahá'ís in the country as of 2005.[15] Lastly, the number of people who have identified with other religions than the ones explicitly mentioned in the 2011 census comes to a total of about 30,000 people.[16]

Paganism

Neopagan groups have emerged in Romania over the latest decade, virtually all of them being ethno-pagan as in the other countries of Eastern Europe,[17] although still small in comparison to other movements such as Ősmagyar Vallás in Hungary and Rodnovery in the Slavic Europe.

The revived ethnic religion of the Romanians is called Zalmoxianism and is based on Thracian mythological sources, with prominence given to the figure of god Zalmoxis.[18] One of the most prominent Zalmoxian groups is the Gebeleizis Association (Romanian: Societatea Gebeleizis).[18]

In the same time, in Romania there is a recognized pagan organization: THE NEW PAGAN DAWN Association,[19][20][21] which tries to defend the rights of the pagan community in Romania and to represent its voice.

Irreligion

Approximately 40,000 people have identified as nonreligious in Romania in the 2011 census, out of which 21,000 declared atheists and 19,000 agnostics. Most of them are concentrated in major cities such as Bucharest or Cluj-Napoca.[22] Irreligion is much lower in Romania than in most other European countries; one of the lowest in Europe.[23]

Attitudes towards religion

In 2008, 19% of Romanians placed "Faith" among maximum four answers to the question "Among the following values, which one is most important in relation to your idea of happiness?". It is the third highest number, after Cyprus (27%), and Malta (26%), at equality with Turkey (19%). The mean in EU-27 was 9%.[24] According to a study by the Soros Foundation, over three quarters of Romanians consider themselves religious people, in a greater amount from rural areas, from women, from elders and from those with low income.[25] Romanians believe in religious dogmas and the church, without absolutizing this belief, showing tolerance towards those who do not fully comply with the divine word, towards other religions and even towards some scientific truths.[25]

In 2011, 49% of Bucharesters declared that they only go to church on social occasions (weddings, Easter, etc.) or not at all.[26] According to preliminary data from the national 2011 census, 98.4% of the population declared themselves adherents of a religious denomination. This figure was contested,[27] suggesting that the number of believers in disproportionately large. The final data for the 2011 national census shows a reduction of this figure to about 93.5% but includes a much larger portion of the population where religion-related data is missing (6.26%).

According to a survey conducted in July 2015, 96.5% of Romanians believe in God, 84.4% believe in saints, 59.6% believe in the existence of heaven, 57.5% in that of hell, and 54.4% in afterlife.[28] 83% of Romanians say they observe Sundays and religious holidays, 74.6% worship when they pass by a church, 65.6% say they pray regularly, 60.2% state they sanctify their belongings, house, car, and 53.6% of Romanians donate regularly to the church.[28]

Religious freedom

The laws of Romania establish the freedom of religion as well as outlawing religious discrimination, and provide a registration framework for religious organizations to receive government recognition and funding (this is not a prerequisite for being able to practice in the country). The government also has programs for compensating religious organizations for property confiscated during World War II and during the rule of the Socialist Republic of Romania. Representatives of minority groups have complained that the government favors the Romanian Orthodox Church over other religious groups, and there have been several incidences of local government and police failing to enforce anti-discrimination laws reliably.[29]

History

During the existence of the Kingdom of Romania in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the government of Romania systematically favored the Orthodox and Romanian Greek Catholic Churches.[30] Non-Christians were denied citizenship until the late 19th century, and even then faced obstacles and limited rights.[31] Antisemitism was a prominent feature of Liberal political currents in the 19th century, before being abandoned by Liberal parties and adopted by left-wing peasant and later fascist groups in the early 20th century.[32][33] During World War II, several hundred thousand Jews were killed by Romanian or German forces in Romania.[34] Although Jews living in territories belonging to Romania prior to the beginning of the war largely avoided this fate, they nevertheless faced harsh antisemitic laws passed by the Antonescu government.[34] During the Socialist era following World War II, the Romanian government exerted significant control over the Orthodox Church and closely monitored religious activity, as well as promoting atheism among the population.[35] Dissident priests were censured, arrested, deported, and/or defrocked, but the Orthodox Church as a whole acquiesced to the government's demands and received support from it.[36]

Historical evolution

| Denominations and religious organizations | 1992 census[37] | 2002 census[37] | 2011 census[37] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Christian denominations | Orthodox | 19,802,389 | 18,817,975 | 16,307,004 |

| Roman Catholic | 1,161,942 | 1,026,429 | 870,774 | |

| Greek Catholic | 223,327 | 191,556 | 150,593 | |

| Old Calendarists | 32,228 | – | – | |

| Old Believers | 28,141 | 38,147 | 32,558 | |

| Serbian Orthodox | – | – | 14,385 | |

| Armenian Apostolic | 2,023 | 775 | 393 | |

| Reformed | 802,454 | 701,077 | 600,932 | |

| Unitarian | 76,708 | 66,944 | 57,686 | |

| Evangelical Augustan | 39,119 | 8,716 | 5,399 | |

| Evangelical Lutheran (Synod-Presbyterian) | 21,221 | 27,112 | 20,168 | |

| Neo-Protestant Christian denominations | Pentecostal | 220,824 | 324,462 | 362,314 |

| Baptist | 109,462 | 126,639 | 112,850 | |

| Seventh-day Adventist | 77,546 | 93,670 | 80,944 | |

| Evangelicals | 49,963 | 44,476 | 42,495 | |

| Romanian Evangelical | – | 18,178 | 15,514 | |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | – | – | 49,820 | |

| Others | Islam | 55,928 | 67,257 | 64,337 |

| Judaism | 9,670 | 6,057 | 3,519 | |

| Other religion | 56,129 | 89,196 | 30,557 | |

| Without religion | 26,314 | 12,825 | 18,917 | |

| Atheism | 10,331 | 8,524 | 20,743 | |

| Undeclared | 8,139 | 11,734 | – | |

| Unavailable | – | – | 1,259,739 |

Charts

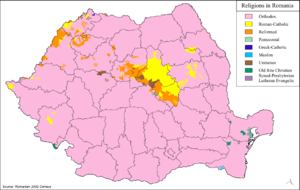

Geographical distribution of denominations

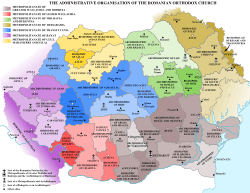

Geographical distribution of denominations Romanian Orthodox Church organization

Romanian Orthodox Church organization.png) Eastern Orthodoxy in Romania (2002 census)

Eastern Orthodoxy in Romania (2002 census).png) Catholic Church in Romania (2002 census)

Catholic Church in Romania (2002 census).png) Protestantism in Romania (2002 census)

Protestantism in Romania (2002 census)

See also

- Religion by country

- Religion in Europe

- Religious persecution in Communist Romania

Notes

- How do European countries differ in religious commitment? Use our interactive map to find out. Pew Research.

- "Culte recunoscute oficial în România". Secretariatul de Stat pentru Culte (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 2016-08-14.

- "Populația stabilă după religie – județe, municipii, orașe, comune". Institutul Național de Statistică (in Romanian).

- Sorin Peneș (28 July 2015). "Sondaj INSCOP: 96,5% dintre români cred în Dumnezeu". Agerpres (in Romanian).

- "The Eastern Catholic Churches 2012" (PDF). Annuario Pontificio. CNEWA.

- "Romania 2014 International Religious Freedom Report" (PDF). U.S. Department of State.

- George Rădulescu (6 May 2010). "Au trădat greco‑catolicii ortodoxia?". Historia.ro (in Romanian).

- "România musulmană. Ce știm despre musulmanii din România ? VIDEO" (in Romanian).

- Mehmet Ali Ekrem (1994). Din istoria turcilor dobrogeni (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Kriterion. ISBN 978-9732603840.

- George Grigore. "Muslims in Romania" (PDF). ISIM Newsletter. 3 (99): 34.

- Maria Oprea (June 2016). "Unde se roagă albanezii musulmani? Geamiile din România". Prietenul Albanezului (in Romanian) (176).

- "Despre noi". Muftiatul Cultului Musulman din România (in Romanian).

- Katarzyna Górak-Sosnowska, ed. (2011). "Muslim institutions and organizations in Romania". Muslims in Poland and Eastern Europe: Widening the European Discourse on Islam. University of Warsaw. p. 268. ISBN 978-83-903229-5-7.

- "Despre noi". Uniunea Democrată a Tătarilor Turco-Musulmani din România (in Romanian).

- "Most Baha'i Nations (2005)". Association of Religion Data Archives.

- "Ce ne spune recensământul din anul 2011 despre religie?" (PDF). Institutul Național de Statistică (in Romanian). October 2013.

- Hubbes László-Attila, Rozália Klára Bakó. "Romanian and Hungarian Ethno-Pagan Organizations on the Net". Reconect Working Paper No. 1/2011. Sapientia – Hungarian University of Transylvania. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1863263. SSRN 1863263. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "Zalmoxianism". Federația Păgână Internațională – România.

- Olteanu, Cosmin (2018-01-02). "Interview with founder of first pagan association from Romania". BlastingNews. Retrieved 2019-07-15.

- Teodora, Munteanu (2017-01-25). "Am vorbit cu românul care conduce un cult satanist și a fost și-n Consiliul Județean al Elevilor". Vice. Retrieved 2019-07-15.

- Cosmin, Olteanu (2019-11-06). "Schimbarea denumirii ROPAGANISM in The New Pagan Dawn Motivele schimbării". Canal Youtube Asociatia THE NEW PAGAN DAWN. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- "Religiile României. Orașul cu cel mai mare procent de atei din țară". inCont.ro (in Romanian).

- Tomka, Miklós (2011). Expanding Religion: Religious Revival in Post-communist Central and Eastern Europe. Walter de Gruyter. p. 75. ISBN 9783110228151.

- "Eurobarometer 69" (PDF). European Commission. November 2008.

- Raluca Popescu. "Atitudini religioase la români: religia și biserica sunt în continuare foarte importante; cu toate acestea, românii au un model religios valoric mai critic și mai tolerant" (PDF). Fundația Soros (in Romanian).

- "Cartografierea socială a Bucureștiului" (PDF). Școala Națională de Studii Politice și Administrative (in Romanian).

- "Asociația Secular-Umanistă din România contestă datele privind religia din rezultatele preliminare ale Recensământului anunțate de INS". HotNews.ro (in Romanian). 30 August 2012.

- "Sondaj: 96,5% dintre români cred în Dumnezeu". Digi24 (in Romanian). 28 July 2015.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2017 Romania, US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

- Statul si cultele religioase

- David Aberbach (2012). The European Jews, Patriotism and the Liberal State 1789-1939: A Study of Literature and Social Psychology. Routledge. pp. 107–9.

- Ornea, Zigu Anii treizeci. Extrema dreaptă românească ("The 1930s: The Romanian Far Right"), Editura Fundației Culturale Române, Bucharest, 1995. p. 395

- The Jewish-Romanian Marxist Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea criticised Poporanist claims in his work on 1907 revolt, Neoiobăgia ("Neo-Serfdom"), arguing that, as favorite victims of prejudice (and most likely to be retaliated against), Jews were least likely to exploit: "[The Jewish tenant's] position is inferior to that of the exploited, for he is not a boyar, a gentleman, but a Yid, as well as to the administration, whose subordinate bodies he may well be able to satisfy, but whose upper bodies remain hostile towards him. His position is also rendered difficult by the antisemitic trend, strong as it gets, and by the hostile public opinion, and by the press, overwhelmingly antisemitic, but mostly by the régime itself - which, while awarding him all the advantages of neo-serfdom on one hand, uses, on the other, his position as a Yid to make of him a distraction and a scapegoat for the régime's sins."

- International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania (28 January 2012). "Executive Summary: Historical Findings and Recommendations" (PDF). Final Report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania. Yad Vashem (The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu. The Romanian Orthodox Church and Post-Communist Democratisation. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 52, No. 8 (Dec., 2000), pp. 1467-1488

- Lucian N. Leustean. Between Moscow and London: Romanian Orthodoxy and National Communism, 1960-1965. The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 85, No. 3 (Jul., 2007), pp. 491-521

- Sorin Negruți (2014). "The evolution of the religious structure in Romania since 1859 to the present day" (PDF). Revista Română de Statistică (6): 46.

Bibliography

- Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu, Religion and Politics in Post-communist Romania, Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-19-530853-0

- Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu, "Religion and Politics in Post-Communist Romania," in Quo Vadis Eastern Europe? Religion, State, Society and Inter-religious Dialogue after Communism, ed. by Ines A. Murzaku (Bologna, Italy: University of Bologna Press, 2009), pp. 221–235.

- Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu, "Politics, National Symbols and the Romanian Orthodox Cathedral," Europe-Asia Studies, vol. 58, no. 7 (November 2006), pp. 1119–1139.

- Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu, "Pulpits, Ballots and Party Cards: Religion and Elections in Romania," Religion, State and Society, vol. 33, no 4 (December 2005), pp. 347–366.

- Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu, "The Devil's Confessors: Priests, Communists, Spies and Informers," East European Politics and Societies, vol. 19, no. 4 (November 2005), pp. 655–685.

- Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu, "Religious Education in Romania," Communist and Post-Communist Studies, vol. 38, no. 3 (September 2005), pp. 381–401.

- Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu, "Religion, Politics and Sexuality in Romania," Europe-Asia Studies, vol. 57, no. 2 (March 2005), pp. 291–310.

- Lavinia Stan and Lucian Turcescu, "The Romanian Orthodox Church and Post-Communist Democratization", Europe-Asia Studies, vol. 52, no. 8 (December 2000), pp. 1467–1488, republished in East European Perspectives, vol. 3, no. 4 (22 February 2001), available online at http://www.rferl.org/content/article/1342524.html, and vol. 3, no. 5 (7 March 2001), available online at http://www.rferl.org/content/article/1342525.html.

- Flora, Gavril; and Georgina Szilagyi; Victor Roudometof (April 2005). "Religion and national identity in post-communist Romania". Journal of Southern Europe and the Balkans. 7 (1): 35–55. doi:10.1080/14613190500036917.