Xuanzang

Xuanzang [ɕɥɛ̌n.tsâŋ] (Chinese: 玄奘; fl. 602 – 664), born Chen Hui / Chen Yi (陈祎), was a Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator who traveled to India in the seventh century and described the interaction between Chinese Buddhism and Indian Buddhism during the early Tang dynasty.[1][2]

Xuanzang | |

|---|---|

A portrait of Xuanzang | |

| Personal | |

| Born | 6 April 602 |

| Died | 5 February 664 (aged 61) |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | East Asian Yogācāra |

| Senior posting | |

Students

| |

| Xuanzang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 玄奘 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chen Hui[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 陳褘 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 陈袆 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chen Yi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 陳禕 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 陈祎 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sanskrit name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sanskrit | ह्यून सान्ग | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

During the journey he visited many sacred Buddhist sites in what are now Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Bangladesh. He was born in what is now Henan province on 6 April 602, and from boyhood he took to reading religious books, including the Chinese classics and the writings of ancient sages.

While residing in the city of Luoyang (in Henan in Central China), Xuanzang was ordained as a śrāmaṇera (novice monk) at the age of thirteen. Due to the political and social unrest caused by the fall of the Sui dynasty, he went to Chengdu in Sichuan, where he was ordained as a bhikṣu (full monk) at the age of twenty. He later traveled throughout China in search of sacred books of Buddhism. At length, he came to Chang'an, then under the peaceful rule of Emperor Taizong of Tang, where Xuanzang developed the desire to visit India. He knew about Faxian's visit to India and, like him, was concerned about the incomplete and misinterpreted nature of the Buddhist texts that had reached China.[3]

He became famous for his seventeen-year overland journey to India (including Nalanda), which is recorded in detail in the classic Chinese text Great Tang Records on the Western Regions, which in turn provided the inspiration for the novel Journey to the West written by Wu Cheng'en during the Ming dynasty, around nine centuries after Xuanzang's death.[4]

Nomenclature, orthography and etymology

| Names | Xuanzang | Tang Sanzang | Xuanzang Sanzang | Xuanzang Dashi | Tang Seng |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 玄奘 | 唐三藏 | 玄奘三藏 | 玄奘大師 | 唐僧 |

| Simplified Chinese | 玄奘 | 唐三藏 | 玄奘三藏 | 玄奘大师 | 唐僧 |

| Pinyin (Mandarin) | Xuánzàng | Táng Sānzàng | Xuánzàng Sānzàng | Xuánzàng Dàshī | Táng Sēng |

| Wade–Giles (Mandarin) | Hsüan-tsang | T'ang San-tsang | Hsüan-tsang San-tsang | Hsüan-tsang Ta-shih | T'ang Seng |

| Jyutping (Cantonese) | Jyun4 Zong6 | Tong4 Saam1 Zong6 | Jyun4 Zong6 Saam1 Zong6 | Jyun4 Zong6 Daai6 Si1 | Tong4 Zang1 |

| Vietnamese | Huyền Trang | Đường Tam Tạng | Huyền Trang Tam Tạng | Huyền Trang Đại Sư | Đường Tăng |

| Japanese | Genjō | Tō-Sanzō | Genjō-sanzō | Genjō-daishi | Tōsō |

| Korean | Hyeonjang | Dang-samjang | Hyeonjang-samjang | Hyeonjang-daesa | Dangseung |

| Meaning | Tang Dynasty Tripiṭaka Master | Tripiṭaka Master Xuanzang | Great Master Xuanzang | Tang Dynasty Monk |

Less common romanizations of "Xuanzang" include Hyun Tsan, Hhuen Kwan, Hiuan Tsang, Hiouen Thsang, Hiuen Tsang, Hiuen Tsiang, Hsien-tsang, Hsyan-tsang, Hsuan Chwang, Huan Chwang, Hsuan Tsiang, Hwen Thsang, Hsüan Chwang, Hhüen Kwān, Xuan Cang, Xuan Zang, Shuen Shang, Yuan Chang, Yuan Chwang, and Yuen Chwang. Hsüan, Hüan, Huan and Chuang are also found. The sound written x in pinyin and hs in Wade–Giles, which represents the s- or sh-like [ɕ] in today's Mandarin, was previously pronounced as the h-like [x] in early Mandarin, which accounts for the archaic transliterations with h.

Another form of his official style was "Yuanzang," written 元奘. It is this form that accounts for such variants as Yuan Chang, Yuan Chwang, and Yuen Chwang.[5]

Tang Monk (Tang Seng) is also transliterated /Thang Seng/.[6]

Another of Xuanzang's standard aliases is Sanzang Fashi (simplified Chinese: 三藏法师; traditional Chinese: 三藏法師; pinyin: Sānzàngfǎshī; lit.: 'Sanzang Dharma (or Law) Teacher'): 法 being a Chinese translation for Sanskrit "Dharma" or Pali/Prakrit Dhamma, the implied meaning being "Buddhism".

"Sanzang" is the Chinese term for the Buddhist canon, or Tripiṭaka, and in some English-language fiction and English translations of Journey to the West, Xuanzang is addressed as "Tripitaka."

Early life

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese Buddhism 汉传佛教 / 漢傳佛教 |

|---|

Chinese: "Buddha" |

|

Major figures |

|

Architecture |

Xuanzang was born Chen Hui (or Chen Yi) on 6 April 602 in Chenhe Village, Goushi Town (Chinese: 緱氏鎮), Luozhou (near present-day Luoyang, Henan) and died on 5 February 664[7] in Yuhua Palace (玉華宮, in present-day Tongchuan, Shaanxi). His family was noted for its erudition for generations, and Xuanzang was the youngest of four children. His ancestor was Chen Shi (陳寔, 104-186), a minister of the Eastern Han dynasty. His great-grandfather Chen Qin (陳欽) served as the prefect of Shangdang (上黨; present-day Changzhi, Shanxi) during the Eastern Wei; his grandfather Chen Kang (陳康) was a professor in the Taixue (Imperial Academy) during the Northern Qi. His father Chen Hui (陳惠) was a conservative Confucian who served as the magistrate of Jiangling County during the Sui dynasty, but later gave up office and withdrew into seclusion to escape the political turmoil that gripped China towards the end of the Sui. According to traditional biographies, Xuanzang displayed a superb intelligence and earnestness, amazing his father by his careful observance of the Confucian rituals at the age of eight. Along with his brothers and sister, he received early education from his father, who instructed him in classical works on filial piety and several other canonical treatises of orthodox Confucianism.

Although his household was essentially Confucian, at a young age, Xuanzang expressed interest in becoming a Buddhist monk like one of his elder brothers. After the death of his father in 611, he lived with his older brother Chén Sù (Chinese: 陳素), later known as Zhǎng jié (Chinese: 長捷), for five years at Jingtu Monastery (Chinese: 淨土寺) in Luoyang, supported by the Sui state. During this time he studied Mahayana as well as various early Buddhist schools, preferring the former.

In 618, the Sui Dynasty collapsed and Xuanzang and his brother fled to Chang'an, which had been proclaimed as the capital of the Tang dynasty, and thence southward to Chengdu, Sichuan. Here the two brothers spent two or three years in further study in the monastery of Kong Hui, including the Abhidharma-kośa Śāstra. When Xuanzang requested to take Buddhist orders at the age of thirteen, the abbot Zheng Shanguo made an exception in his case because of his precocious knowledge.

Taking the monastic name Xuanzang, he was fully ordained as a monk in 622, at the age of twenty.[8] The myriad contradictions and discrepancies in the texts at that time prompted Xuanzang to decide to go to India and study in the cradle of Buddhism. He subsequently left his brother and returned to Chang'an to study foreign languages and to continue his study of Buddhism. He began his mastery of Sanskrit in 626, and probably also studied Tocharian. During this time, Xuanzang also became interested in the metaphysical Yogacara school of Buddhism.

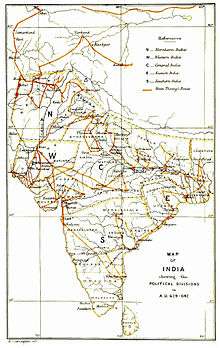

Pilgrimage

In 627, Xuanzang reportedly had a dream that convinced him to journey to India. Tang China and the Göktürks were at war at the time and Emperor Taizong of Tang had prohibited foreign travel. Xuanzang persuaded some Buddhist guards at Yumen Pass and slipped out of the empire through Liangzhou (Gansu) and Qinghai in 629.[9] He subsequently traveled across the Gobi Desert to Kumul (modern Hami City), thence following the Tian Shan westward.

He arrived in Turpan in 630. Here he met the king of Turpan, a Buddhist who equipped him further for his travels with letters of introduction and valuables to serve as funds. The hottest mountain in China, the Flaming Mountains, is located in Turpan and was depicted in the Journey to the West.

Moving further westward, Xuanzang escaped robbers to reach Karasahr, then toured the non-Mahayana monasteries of Kucha. Further west he passed Aksu before turning northwest to cross the Tian Shan's Bedel Pass into modern Kyrgyzstan. He skirted Issyk Kul before visiting Tokmak on its northwest, and met the great Khagan of the Göktürks,[10] whose relationship to the Tang emperor was friendly at the time. After a feast, Xuanzang continued west then southwest to Tashkent, capital of modern Uzbekistan. From here, he crossed the desert further west to Samarkand. In Samarkand, which was under Persian influence, the party came across some abandoned Buddhist temples and Xuanzang impressed the local king with his preaching. Setting out again to the south, Xuanzang crossed a spur of the Pamirs and passed through the famous Iron Gates. Continuing southward, he reached the Amu Darya and Termez, where he encountered a community of more than a thousand Buddhist monks.

Further east he passed through Kunduz, where he stayed for some time to witness the funeral rites of Prince Tardu,[11] who had been poisoned. Here he met the monk Dharmasimha, and on the advice of the late Tardu made the trip westward to Balkh (modern Afghanistan), to see the Buddhist sites and relics, especially the Nava Vihara, which he described as the westernmost vihara in the world. Here Xuanzang also found over 3,000 non-Mahayana monks, including Prajnakara (般若羯羅 or 慧性),[12] a monk with whom Xuanzang studied early Buddhist scriptures. He acquired the important text of the Mahāvibhāṣa (Chinese: 大毗婆沙論) here, which he later translated into Chinese.

Prajñakara then accompanied the party southward to Bamyan, where Xuanzang met the king and saw tens of non-Mahayana monasteries, in addition to the two large Buddhas of Bamiyan carved out of the rockface. The party then resumed their travel eastward, crossing the Shibar Pass and descending to the regional capital of Kapisi (about 60 kilometres (37 mi) north of modern Kabul), which sported over 100 monasteries and 6000 monks, mostly Mahayana. This was part of the fabled old land of Gandhara. Xuanzang took part in a religious debate here and demonstrated his knowledge of many Buddhist schools. Here he also met the first Jains and Hindu of his journey. He pushed on to Adinapur[13] (later named Jalalabad) and Laghman, where he considered himself to have reached India. The year was 630.

Arrival in India

Xuanzang left Adinapur, which had few Buddhist monks, but many stupas and monasteries. His travels included passing through Hunza and the Khyber Pass to the east, reaching the former capital of Gandhara, Purushapura (Peshawar), on the other side. Peshawar was nothing compared to its former glory, and Buddhism was declining in the region. Xuanzang visited a number of stupas around Peshawar, notably the Kanishka stupa. This stupa was built just southeast of Peshawar, by a former king of the city. In 1908, it was rediscovered by D.B. Spooner with the help of Xuanzang's account.

Xuanzang left Peshawar and traveled northeast to the Swat Valley. Reaching Oḍḍiyāna, he found 1,400-year-old monasteries, that had previously supported 18,000 monks. The remnant monks were of the Mahayana school. Xuanzang continued northward and into the Buner Valley, before doubling back via Shahbaz Garhi to cross the Indus river at Hund. He visited Taxila which was desolate and half-ruined, and found most of its sangharamas still ruined and desolate with the state of having become a dependency of Kashmir with the local leaders fighting amongst themselves for power. Only a few monks remained there. He noted that it had some time previously been a subject of Kapisa. He went to Kashmir in 631 where he met a talented monk Samghayasas (僧伽耶舍) and studied there. In Kashmir, he found himself in another center of Buddhist culture and describes that there were over 100 monasteries and over 5,000 monks in the area. Between 632 and early 633, he studied with various monks, including 14 months with Vinītaprabha (毘膩多缽臘婆 or 調伏光), 4 months with Candravarman (旃達羅伐摩 or 月胃), and "a winter and half a spring" with Jayagupta (闍耶毱多). During this time, Xuanzang wrote about the Fourth Buddhist council that took place nearby, ca. 100 AD, under the order of King Kanishka of Kushana. He visited Chiniot and Lahore as well and provided the earliest writings available on the ancient cities. In 634, Xuanzang arrived in Matipura (秣底補羅), known as Mandawar today.[12][14][15][16][17]

In 634, he went east to Jalandhar in eastern Punjab, before climbing up to visit predominantly non-Mahayana monasteries in the Kulu valley and turning southward again to Bairat and then Mathura, on the Yamuna River. Mathura had 2,000 monks of both major Buddhist branches, despite being Hindu-dominated. Xuanzang traveled up the river to Shrughna, also mentioned in the works of Udyotakara, before crossing eastward to Matipura, where he arrived in 635, having crossed the river Ganges. At Matipura Monastery, Xuanzang studied under Mitrasena.[18] From here, he headed south to Sankasya (Kapitha, then onward to Kannauj, the grand capital of the Empire of Harsha under the northern Indian emperor Harsha. It is believed he also visited Govishan present-day Kashipur in the Harsha era, in 636, Xuanzang encountered 100 monasteries of 10,000 monks (both Mahayana and non-Mahayana), and was impressed by the king's patronage of both scholarship and Buddhism. Xuanzang spent time in the city studying early Buddhist scriptures, before setting off eastward again for Ayodhya (Saketa), the homeland of the Yogacara school. Xuanzang now moved south to Kausambi (Kosam), where he had a copy made from an important local image of the Buddha.

Xuanzang now returned northward to Shravasti Bahraich, traveled through Terai in the southern part of modern Nepal (here he found deserted Buddhist monasteries) and thence to Kapilavastu, his last stop before Lumbini, the birthplace of Buddha.[19]

In 637, Xuanzang set out from Lumbini to Kusinagara, the site of Buddha's death, before heading southwest to the deer park at Sarnath where Buddha gave his first sermon, and where Xuanzang found 1,500 resident monks. Travelling eastward, at first via Varanasi, Xuanzang reached Vaisali, Pataliputra (Patna) and Bodh Gaya. He was then accompanied by local monks to Nalanda, the greatest Indian university of the Indian state of Bihar, where he spent at least the next two years, He visited Champa Monastery, Bhagalpur.[20][21] He was in the company of several thousand scholar-monks, whom he praised. Xuanzang studied logic, grammar, Sanskrit, and the Yogacara school of Buddhism during his time at Nalanda. René Grousset notes that it was at Nalanda (where an "azure pool winds around the monasteries, adorned with the full-blown cups of the blue lotus; the dazzling red flowers of the lovely kanaka hang here and there, and outside groves of mango trees offer the inhabitants their dense and protective shade") that Xuanzang met the venerable Silabhadra, the monastery's superior.[22] Silabhadra had dreamt of Xuanzang's arrival and that it would help spread far and wide the Holy Law.[23] Grousset writes: "The Chinese pilgrim had finally found the omniscient master, the incomparable metaphysician who was to make known to him the ultimate secrets of the idealist systems." The founders of Mahayana idealism, Asanga and Vasubandhu, trained Dignaga, he trained Dharmapala, and Dharmapala had in turn trained Silabhadra. Silabhadra was thus in a position to make available to the Sino-Japanese world the entire heritage of Buddhist idealism, and the Siddhi Xuanzang's great philosophical treatise is none other than the Summa of this doctrine, the fruit of seven centuries of Indian Buddhist thought."[24]

From Nalanda, Xuanzang traveled through several kingdoms, including Pundranagara, to the capital of Pundravardhana, identified with modern Mahasthangarh, in present-day Bangladesh. There Xuanzang found 20 monasteries with over 3,000 monks studying both the Hinayana and the Mahayana. One of them was the Vāśibhã Monastery (Po Shi Po), where he found over 700 Mahayana monks from all over East India.[25][26] He also visited Somapura Mahavihara at Paharpur in the district of Naogaon, in modern-day Bangladesh.

Xuanzang turned southward and traveled to Andhradesa to visit the Viharas at Amaravati and Nagarjunakonda. He stayed at Amaravati and studied 'Abhidhammapitakam'.[27] He observed that there were many Viharas at Amaravati and some of them were deserted. He later proceeded to Kanchi, the imperial capital of Pallavas, and a strong center of Buddhism. He continued traveling to Nasik, Ajanta, Malwa, from there he went to Multan and Pravata before returning to Nalanda again.[28]

At the invitation of Hindu king Kumar Bhaskar Varman, he went east to the ancient city of Pragjyotishpura in the kingdom of Kamarupa after crossing the Karatoya and spent three months in the region. Before going to Kamarupa he visited Sylhet what is now a modern city Of Bangladesh. He gives a detailed account of the culture and people of Sylhet. Later, the king escorted Xuanzang back to the Kannauj at the request of the king Harshavardhana, who was an ally of Kumar Bhaskar Varman, to attend a great Buddhist Assembly there which was attended by both of the kings as well as several other kings from neighboring kingdoms, Buddhist monks, Brahmans, and Jains. King Harsha invited Xuanjang to Kumbh Mela in Prayag where he witnessed king Harsha's generous distribution of gifts to the poor.[29]

After visiting Prayag he returned to Kannauj where he was given a grand farewell by king Harsha. Traveling through the Khyber Pass of the Hindu Kush, Xuanzang passed through Kashgar, Khotan, and Dunhuang on his way back to China. He arrived in the capital, Chang'an, on the seventh day of the first month of 645, 16 years after he left Chinese territory, and a great procession celebrated his return.[30]

Return to China

On his return to China in AD 645, Xuanzang was greeted with much honor but he refused all high civil appointments offered by the still-reigning emperor, Emperor Taizong of Tang. Instead, he retired to a monastery and devoted his energy to translating Buddhist texts until his death in AD 664. According to his biography, he returned with, "over six hundred Mahayana and Hinayana texts, seven statues of the Buddha and more than a hundred sarira relics."[31] In celebration of Xuanzang's extraordinary achievement in translating the Buddhist texts, Emperor Gaozong of Tang ordered renowned Tang calligrapher Chu Suiliang (褚遂良) and inscriber Wan Wenshao (萬文韶) to install two stele stones, collectively known as The Emperor’s Preface to the Sacred Teachings (雁塔聖教序), at the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda.[32]

Chinese Buddhism (influence)

During Xuanzang's travels, he studied with many famous Buddhist masters, especially at the famous center of Buddhist learning at Nalanda. When he returned, he brought with him some 657 Sanskrit texts. With the emperor's support, he set up a large translation bureau in Chang'an (present-day Xi'an), drawing students and collaborators from all over East Asia. He is credited with the translation of some 1,330 fascicles of scriptures into Chinese. His strongest personal interest in Buddhism was in the field of Yogācāra (瑜伽行派), or Consciousness-only (唯識).

The force of his own study, translation, and commentary of the texts of these traditions initiated the development of the Faxiang school (法相宗) in East Asia. Although the school itself did not thrive for a long time, its theories regarding perception, consciousness, Karma, rebirth, etc. found their way into the doctrines of other more successful schools. Xuanzang's closest and most eminent student was Kuiji (窺基) who became recognized as the first patriarch of the Faxiang school. Xuanzang's logic, as described by Kuiji, was often misunderstood by scholars of Chinese Buddhism because they lack the necessary background in Indian logic.[33] Another important disciple was the Korean monk Woncheuk.

Xuanzang was known for his extensive but careful translations of Indian Buddhist texts to Chinese, which have enabled subsequent recoveries of lost Indian Buddhist texts from the translated Chinese copies. He is credited with writing or compiling the Cheng Weishi Lun as a commentary on these texts. His translation of the Heart Sutra became and remains the standard in all East Asian Buddhist sects; as well, this translation of the Heart Sutra was generally admired within the traditional Chinese gentry and is still widely respected as numerous renowned past and present Chinese calligraphers have penned its texts as their artworks.[34] He also founded the short-lived but influential Faxiang school of Buddhism. Additionally, he was known for recording the events of the reign of the northern Indian emperor, Harsha.

The perfection of Wisdom Sutra

Xuanzang returned to China with three copies of the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra.[35] Xuanzang, with a team of disciple translators, commenced translating the voluminous work in 660 CE, using all three versions to ensure the integrity of the source documentation.[35] Xuanzang was being encouraged by a number of his disciple translators to render an abridged version. After a suite of dreams quickened his decision, Xuanzang determined to render an unabridged, complete volume, faithful to the original of 600 chapters.[36]

Autobiography and biography

In 646, under the Emperor's request, Xuanzang completed his book Great Tang Records on the Western Regions (大唐西域記), which has become one of the primary sources for the study of medieval Central Asia and India.[37] This book was first translated into French by the Sinologist Stanislas Julien in 1857.

There was also a biography of Xuanzang written by the monk Huili (慧立). Both books were first translated into English by Samuel Beal, in 1884 and 1911 respectively.[38][39] An English translation with copious notes by Thomas Watters was edited by T.W. Rhys Davids and S.W. Bushell, and published posthumously in London in 1905.

Legacy

Xuanzang's work, the Great Tang Records on the Western Regions, is the longest and most detailed account of the countries of Central and South Asia that has been bestowed upon posterity by a Chinese Buddhist pilgrim. While his main purpose was to obtain Buddhist books and to receive instruction on Buddhism while in India, he ended up doing much more. He has preserved the records of the political and social aspects of the lands he visited.

His record of the places visited by him in Bengal — mainly Raktamrittika near Karnasuvarna, Pundranagara and its environs, Samatata, Tamralipti and Harikela— have been very helpful in the recording of the archaeological history of Bengal. His account has also shed welcome light on the history of 7th century Bengal, especially the Gauda kingdom under Shashanka, although at times he can be quite partisan.

Xuanzang obtained and translated 657 Sanskrit Buddhist works. He received the best education on Buddhism he could find throughout India. Much of this activity is detailed in the companion volume to Xiyu Ji, the Biography of Xuanzang written by Huili, entitled the Life of Xuanzang.

His version of the Heart Sutra is the basis for all Chinese commentaries on the sutra, and recitations throughout China, Korea, and Japan.[40] His style was, by Chinese standards, cumbersome and overly literal, and marked by scholarly innovations in terminology; usually, where another version by the earlier translator Kumārajīva exists, Kumārajīva's is more popular.[40]

In fiction

Xuanzang's journey along the Silk Road, and the legends that grew up around it, inspired the Ming novel Journey to the West, one of the great classics of Chinese literature. The fictional counterpart Tang Sanzang is the reincarnation of the Golden Cicada, a disciple of Gautama Buddha, and is protected on his journey by three powerful disciples. One of them, the monkey, was a popular favorite and profoundly influenced Chinese culture and contemporary Japanese manga and anime (including the popular Dragon Ball and Saiyuki series), and became well known in the West by Arthur Waley's translation and later the cult TV series Monkey.

In the Yuan Dynasty, there was also a play by Wu Changling (吳昌齡) about Xuanzang obtaining scriptures.

In the year 2016 was released the movie Da Tang Xuan Zang as an official Chinese and Indian Production which, of his amazing camera work, was preselected in this year for Best Foreign Language Film at the 89th Academy Awards but at the end, it was not nominated.

Xuanzang appears in the mobile game Fate/Grand Order as a "Caster" class "Servant" named "Xuanzang Sanzang". To continue the Fate series' tradition of inverting the gender of historical and mythological characters, Xuangzang appears as a woman. Xuanzang Sanzang appears as an important character in the game's sixth Singularity, Camelot.

Relics

A skull relic purported to be that of Xuanzang was held in the Temple of Great Compassion, Tianjin until 1956 when it was taken to Nalanda - allegedly by the Dalai Lama - and presented to India. The relic was in the Patna Museum for a long time but was moved to a newly built memorial hall in Nalanda in 2007.[41] The Wenshu Monastery in Chengdu, Sichuan province also claims to have part of Xuanzang's skull.

Part of Xuanzang's remains were taken from Nanjing by soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army in 1942, and are now enshrined at Yakushi-ji in Nara, Japan.[42]

Works

- Watters, Thomas (1904). On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India, 629-645 A.D. Vol.1. Royal Asiatic Society, London. Volume 2. Reprint. Hesperides Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1-4067-1387-9.

- Beal, Samuel (1884). Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, by Hiuen Tsiang. 2 vols. Translated by Samuel Beal. London. 1884. Reprint: Delhi. Oriental Books Reprint Corporation. 1969. Vol. 1, Vol. 2

- Julien, Stanislas, (1857/1858). Mémoires sur les contrées occidentales, L'Imprimerie impériale, Paris. Vol.1 Vol.2

- Li, Rongxi (translator) (1995). The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. Berkeley, California. ISBN 1-886439-02-8

See also

- China-India relations

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- Chinese Buddhism

- Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit

- Chinese Translation Theory

- Chinese exploration

- Faxian

- Yijing

- Zhang Qian

- Hyecho

- Ibn Battuta

- Marco Polo

Notes

- There is some dispute over the Chinese character for Xuanzang's given name at birth. Historical records provide two different Chinese characters, 褘 and 禕, both are similar in writing except that the former has one more stroke than the latter. Their pronunciations in pinyin are also different: the former is pronounced as Huī while the latter is pronounced as Yī. See here and here. (Both sources are in Chinese.)

References

Citations

- Wriggins, Sally (27 November 2003). The Silk Road Journey With Xuanzang (1 ed.). Washington DC: Westview press (Penguin). ISBN 978-0813365992.

- Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education. p. 563. ISBN 9788131716779.

- Wriggins, Sally (27 November 2003). The Silk Road Journey With Xuanzang. New York: Westview (Penguin). ISBN 978-0813365992.

- Cao Shibang (2006). "Fact versus Fiction: From Record of the Western Regions to Journey to the West". In Wang Chichhung (ed.). Dust in the Wind: Retracing Dharma Master Xuanzang's Western Pilgrimage. p. 62. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Rhys Davids, T. W. (1904). On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India 629–645 A.D. London: Royal Asiatic Society. pp. xi–xii.

- Christie 123, 126, 130, and 141

- Wriggins 1996, pp. 7, 193

- Lee, Der Huey. "Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang) (602—664)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- "Note sur la chronologie du voyage de Xuanzang." Étienne de la Vaissière. Journal Asiatique, Vol. 298, 1. (2010), pp. 157-168. Eh? Liangzhou, Gansu, Qinghai, and the Gobi are all east of Yumen.

- Tong Yabghu Qaghan or possibly his son

- Baumer, Hist Cent Asia,2,200 says Tardush Shad (see Shad (prince)), eldest son of Tong Yabghu Qaghan advanced as far as the Indus. In 630 his son Ishbara Yabghu had his new wife poison him, 'which Xuanzang witnessed'.

- "玄奘法師年譜". ccbs.ntu.edu.tw. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and monthly record (Great Britain) Volume 1, page 43 (Science) 1879.

- John Marshall (20 June 2013). A Guide to Taxila. Cambridge University Press. pp. 39, 46. ISBN 9781107615441.

- Elizabeth Errington, Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis. Persepolis to the Punjab: Exploring Ancient Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. British Museum Press. p. 134.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Stephen Gosch, Peter Stearns (12 December 2007). Premodern Travel in World History. Routledge. p. 89. ISBN 9781134583706.

- trans. by Samuel Beal. Si-yu-ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World. Motilal Banarasidass.

- Men and Thought in Ancient India by Radhakumud Mookerji, 1912 edition published by McMillan and Co., reprinted by Motilal Banarasidass (1996) page 169

- Nakamura, Hajime (2000). Gotama Buddha. Kosei. pp. 47, 53–54. ISBN 978-4-333-01893-2.

- "XUANZANG'S TRAVELS IN BIHAR (637-642 CE) - Google Arts & Culture".

- "Champa monastery, (in) Bhagalpur, Bihar, IN - Mapping Buddhist Monasteries". monastic-asia.wikidot.com.

- René Grousset. In the Footsteps of the Buddha. JA Underwood (trans) Orion Press. New York. 1971. p159-160.

- Rene Grousset. In the Footsteps of the Buddha. JA Underwood (trans) Orion Press. New York. 1971.p161

- Rene Grousset. In the Footsteps of the Buddha. JA Underwood (trans) Orion Press. New York. 1971 p161

- Watters II (1996), pp. 164-165.

- Li (1996), pp. 298-299

- Rao, G. Venkataramana (3 November 2016). "Xuan Zang stayed in Vijayawada to study Buddhist scriptures". The Hindu.

- Xuanzang Pilgrimage Route Google Maps, retrieved July 17, 2016

- Assembly at Prayag Ancient Indian History and Culture by Sailendra Nath Sen, page 260, ISBN 81-224-1198-3, 2nd ed. 1999, New Age International(P) Limited Publishers

- Wriggins 186-188.

- Strong 2007, p. 188.

- "The Emperor's Preface to the Sacred Teachings". Vincent's Calligraphy. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- See Eli Franco, "Xuanzang's proof of idealism." Horin 11 (2004): 199-212.

- "Heart Sutra Buddhism". Vincent's Calligraphy. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- Wriggins 1996, pg.206

- Wriggins 1996, pg. 207

- Deeg, Max (2007). „Has Xuanzang really been in Mathurā? : Interpretatio Sinica or Interpretatio Occidentalia — How to Critically Read the Records of the Chinese Pilgrim.“ - In: 東アジアの宗教と文化 : 西脇常記教授退休記念論集 = Essays on East Asian religion and culture: Festschrift in honor of Nishiwaki Tsuneki on the occasion of his 65th birthday / クリスティアン・ウィッテルン, 石立善編集 = ed. by Christian Wittern und Shi Lishan. - 京都 [Kyōto] : 西脇常記教授退休記念論集編集委員會; 京都大���人文科學研究所; Christian Wittern, 2007, pp. 35 - 73. See p. 35

- Beal 1884

- Beal 1911

- Nattier 1992, pg. 188

- of famous Chinese monk moved to the new memorial hall in N India China.com, Xinhua, February 11, 2007

- Arai, Kiyomi. "Yakushiji offers peace of mind." (originally from Yomiuri Shinbun). Buddhist Channel Website. 25 September 2008. Accessed 23 May 2009.

Works cited

- Beal, Samuel, trans. (1911). The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang. Translated from the Chinese of Shaman (monk) Hwui Li. London. 1911. Reprint Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi. 1973.

- Bernstein, Richard (2001). Ultimate Journey: Retracing the Path of an Ancient Buddhist Monk (Xuanzang) who crossed Asia in Search of Enlightenment. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. ISBN 0-375-40009-5.

- Christie, Anthony (1968). Chinese Mythology. Feltham, Middlesex: Hamlyn Publishing. ISBN 0600006379.

- Gordon, Stewart. When Asia was the World: Traveling Merchants, Scholars, Warriors, and Monks who created the "Riches of the East" Da Capo Press, Perseus Books, 2008. ISBN 0-306-81556-7.

- Julien, Stanislas (1853). Histoire de la vie de Hiouen-Thsang, par Hui Li et Yen-Tsung, Paris.

- Li, Yongshi, trans. (1959). The Life of Hsuan Tsang by Huili. Chinese Buddhist Association, Beijing.

- Li, Rongxi, trans. (1995). A Biography of the Tripiṭaka Master of the Great Ci’en Monastery of the Great Tang Dynasty. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. Berkeley, California. ISBN 1-886439-00-1

- Nattier, Jan. "The Heart Sutra: A Chinese Apocryphal Text?". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Vol. 15 (2), p. 153-223. (1992) PDF

- Saran, Mishi (2005). Chasing the Monk’s Shadow: A Journey in the Footsteps of Xuanzang. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-306439-8

- Sun Shuyun (2003). Ten Thousand Miles Without a Cloud (retracing Xuanzang's journeys). Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-00-712974-2

- Waley, Arthur (1952). The Real Tripitaka, and Other Pieces. London: G. Allen and Unwin.

- Watters, Thomas (1904–05). On Yuan Chwang’s Travels in India. London, Royal Asiatic Society. Reprint, Delhi, Munshiram Manoharlal, 1973.

- Wriggins, Sally Hovey. Xuanzang: A Buddhist Pilgrim on the Silk Road. Westview Press, 1996. Revised and updated as The Silk Road Journey With Xuanzang. Westview Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8133-6599-6.

- Wriggins, Sally Hovey (2004). The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-6599-6.

- Yu, Anthony C. (ed. and trans.) (1980 [1977]). The Journey to the West. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-97150-6 (fiction)

Further reading

- Bhat, R. B., & Wu, C. (2014). Xuan Zhang's mission to the West with Monkey King. New Delhi : Aditya Prakashan, 2014.

- Sen, T. (2006). The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing, Education About Asia 11 (3), 24-33

- Weerawardane, Prasani (2009). Journey to the West: Dusty Roads, Stormy Seas, and Transcendence, biblioasia 5 (2), 14-18

- Kahar Barat (2000). The Uygur-Turkic Biography of the Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Pilgrim Xuanzang: Ninth and Tenth Chapters. Indiana University, Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies. ISBN 978-0-933070-46-2.

- Jain, Sandhya, & Jain, Meenakshi (2011). The India they saw: Foreign accounts. New Delhi: Ocean Books.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Xuanzang |

- Hiuen Tsang A Poem on Xuanzang in Asia Literary Review by Indian poet-diplomat Abhay K.

- A Tour of Hiuen Tsang Museum Nalanda A Video Tour of Xuanzang Museum Nalanda

- Xuanzang Memorial, Nava Nalanda Mahavihara on Google Cultural Institute

- Details of Xuanzang's life and works Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- History of San Zang A narration of Xuan Zang's journey to India.

- "大慈恩寺三藏法师传 (全文)". Archived from the original on 13 February 2005. Chinese text of The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang, by Shaman (monk) Hwui Li (Hui Li) (沙门慧立)

- Verses Delineating the Eight Consciousnesses by Tripitaka Master Xuanzang of the Tang Dynasty, translation, and explanation by Ronald Epstein (1986)