Arthur Waley

Arthur David Waley CH CBE (born Arthur David Schloss, 19 August 1889 – 27 June 1966) was an English orientalist and sinologist who achieved both popular and scholarly acclaim for his translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry. Among his honours were the CBE in 1952, the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry in 1953, and he was invested as a Companion of Honour in 1956.[1]

Arthur Waley | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A portrait of Waley by Ray Strachey | |||||||||

| Born | 19 August 1889 Tunbridge Wells, Kent, England | ||||||||

| Died | 27 June 1966 (aged 76) London, England | ||||||||

| Resting place | Highgate Cemetery | ||||||||

| Alma mater | Cambridge University (did not graduate) | ||||||||

| Known for | Chinese/Japanese translations | ||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 亞瑟・偉利 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 亚瑟・伟利 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kana | アーサー・ウェイリ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

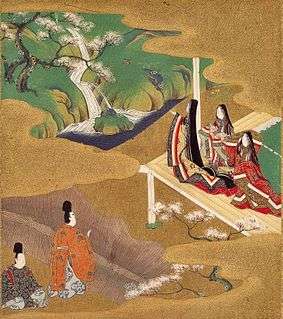

Although highly learned, Waley avoided academic posts and most often wrote for a general audience. He chose not to be a specialist but to translate a wide and personal range of classical literature. Starting in the 1910s and continuing steadily almost until his death in 1966, these translations started with poetry, such as A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (1918) and Japanese Poetry: The Uta (1919), then an equally wide range of novels, such as The Tale of Genji (1925–26), an 11th-century Japanese work, and Monkey, from 16th-century China. Waley also presented and translated Chinese philosophy, wrote biographies of literary figures, and maintained a lifelong interest in both Asian and Western paintings.

A recent evaluation called Waley "the great transmitter of the high literary cultures of China and Japan to the English-reading general public; the ambassador from East to West in the first half of the 20th century", and went on to say that he was "self-taught, but reached remarkable levels of fluency, even erudition, in both languages. It was a unique achievement, possible (as he himself later noted) only in that time, and unlikely to be repeated."[2]

Life

Arthur Waley was born Arthur David Schloss on 19 August 1889 in Tunbridge Wells, Kent, England, the son of an economist, David Frederick Schloss. He was educated at Rugby School and entered King's College, Cambridge in 1907 on a scholarship to study the Classics, but left in 1910 due to eye problems that hindered his ability to study.[3]

Waley briefly worked in an export firm in an attempt to please his parents, but in 1913 he was appointed Assistant Keeper of Oriental Prints and Manuscripts at the British Museum.[3] Waley's supervisor at the Museum was the poet and scholar Laurence Binyon, and under his nominal tutelage Waley taught himself to read Classical Chinese and Classical Japanese, partly to help catalogue the paintings in the Museum's collection. Notwithstanding his ability in reading classical literature, Waley never learned to speak either modern Mandarin Chinese or Japanese, in part because he never visited either China or Japan.[3]

Waley was of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. He changed his surname from Schloss in 1914, when, like many others in England with German surnames, he sought to avoid the anti-German prejudice common in Britain during the First World War.[3]

Waley entered into a lifelong relationship with the English ballet dancer, orientalist, dance critic, and dance researcher Beryl de Zoete, whom he met in 1918 but never married.[4]

Waley left the British Museum in 1929 to devote himself fully to writing and translation, and never held a full-time job again, except for a four-year stint in the Ministry of Information during the Second World War.[3]

Waley lived in Bloomsbury and had a number of friends among the Bloomsbury Group, many of whom he had met when he was an undergraduate. He was one of the earliest to recognise Ronald Firbank as an accomplished author and, together with Osbert Sitwell, provided an introduction to the first edition of Firbank's collected works.

Ezra Pound was instrumental in getting Waley's first translations into print in The Little Review. His view of Waley's early work was mixed, however. As he wrote to Margaret Anderson, the editor of the Little Review, in a letter of 2 July 1917: "Have at last got hold of Waley's translations from Po chu I. Some of the poems are magnificent. Nearly all the translations marred by his bungling English and defective rhythm. ... I shall try to buy the best ones, and to get him to remove some of the botched places. (He is stubborn as a donkey, or a scholar.)" One may consider that this arrogance was unfounded, given Pound's innumerable mistranslations from Chinese. In his introduction to his translation of The Way and its Power Waley explains that he was careful to put meaning above style in translations where meaning would be reasonably considered of more importance to the modern western reader.

Waley married Alison Grant Robertson in May 1966, one month before his death on 27 June. He is buried in Highgate Cemetery.[5]

Sacheverell Sitwell, who considered Waley "the greatest scholar and the person with most understanding of all human arts" that he had known in his lifetime, later recalled Waley's last days,

when he lay dying from a broken back and from cancer of the spine, and in very great pain, but refused to be given any drug or sedative. He had the courage to do so because he wanted to be conscious during the last hours of being alive, the gift which was ebbing and fading and could never be again. In this way during those few days he listened to string quartets by Haydn, and had his favourite poems read to him. And then he died.[6]

Honours

Waley was elected an honorary fellow of King's College, Cambridge in 1945, received the Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) honor in 1952, the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry in 1953, and the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) in 1956.

Works

Jonathan Spence wrote of Waley's translations that he

selected the jewels of Chinese and Japanese literature and pinned them quietly to his chest. No one ever did anything like it before, and no one will ever do it again. There are many westerners whose knowledge of Chinese or Japanese is greater than his, and there are perhaps a few who can handle both languages as well. But they are not poets, and those who are better poets than Waley do not know Chinese or Japanese. Also the shock will never be repeated, for most of the works that Waley chose to translate were largely unknown in the West, and their impact was thus all the more extraordinary.[7]

His many translations include A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (1918), Japanese Poetry: The Uta (1919), The No Plays of Japan (1921), The Tale of Genji (published in 6 volumes from 1921–33), The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon (1928), The Kutune Shirka (1951), Monkey (1942, an abridged version of Journey to the West), The Poetry and Career of Li Po (1959) and The Secret History of the Mongols and Other Pieces (1964). Waley received the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for his translation of Monkey, and his translations of the classics, the Analects of Confucius and The Way and Its Power (Tao Te Ching), are still in print, as is his interpretive presentation of classical Chinese philosophy, Three Ways of Thought in Ancient China (1939).

Waley's translations of verse are widely regarded as poems in their own right, and have been included in many anthologies such as the Oxford Book of Modern Verse 1892–1935, The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse and the Penguin Book of Contemporary Verse (1918–1960) under Waley's name. Many of his original translations and commentaries have been re-published as Penguin Classics and Wordsworth Classics, reaching a wide readership.

Despite translating many Chinese and Japanese classical texts into English, Waley never travelled to either country, or anywhere else in East Asia. In his preface to The Secret History of the Mongols he writes that he was not a master of many languages, but claims to have known Chinese and Japanese fairly well, a good deal of Ainu and Mongolian, and some Hebrew and Syriac.

The composer Benjamin Britten set six translations from Waley's Chinese Poems (1946) for high voice and guitar in his song cycle Songs from the Chinese (1957).

Selected works

Translations

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Arthur Waley |

- A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems, 1918

- More Translations from the Chinese (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1919).

- The Story of Ts'ui Ying-ying (Yingying zhuan) – p. 101–113[8]

- The Story of Miss Li (The Tale of Li Wa) – pp. 113–136[8]

- Japanese Poetry: The Uta, 1919. A selection mostly drawn from the Man'yōshū and the Kokinshū.

- The Nō Plays of Japan, 1921

- The Temple and Other Poems, 1923

- The Tale of Genji, by Lady Murasaki, 1925–1933

- The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon, 1928

- The Way and Its Power: A Study of the Tao Te Ching and its Place in Chinese Thought, 1934. A commentary on Tao Te ching, attributed to Laozi, and full translation.

- The Book of Songs (Shih Ching), 1937

- The Analects of Confucius, 1938

- Three Ways of Thought in Ancient China, 1939

- Translations from the Chinese, a compilation, 1941

- Monkey, 1942, translation of 30 of the 100 chapters of Wu Cheng'en's Journey to the West

- Chinese Poems, 1946

- 77 Poems, Alberto de Lacerda, 1955

- The Nine Songs: A Study of Shamanism in Ancient China, Qu Yuan, 1955

- Yuan Mei: Eighteenth-Century Chinese Poet, 1956

- Ballads and Stories from Tun-Huang, 1960

Original works

- Introduction to the Study of Chinese Painting, 1923

- The Life and Times of Po Chü-I, 1949

- The Poetry and Career of Li Po, 1950 (with some original translations)

- The Real Tripitaka and Other Pieces, 1952 (with some original and previously published translations)

- The Opium War through Chinese Eyes, 1958

- The Secret History of the Mongols, 1963 (with original translations)

See also

References

- Johns (1983), p. 179.

- E. Bruce Brooks, "Arthur Waley", Warring States Project, University of Massachusetts.

- Honey (2001), p. 225.

- "Papers of Beryl de Zoete". Rutgers University.

- "Obituary of Arthur Waley". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Sacheverell Sitwell. For Want of the Golden City (New York: John Day, 1973) p. 255

- Jonathan Spence. "Arthur Waley," in Chinese Roundabout (New York: Norton, 1992 ISBN 0393033554) pp. 329-330

- Nienhauser, William H. "Introduction." In: Nienhauser, William H. (editor). Tang Dynasty Tales: A Guided Reader. World Scientific, 2010. ISBN 9814287288, 9789814287289. p. xv.

Sources

- "Arthur Waley, 76, Orientalist, Dead; Translator of Chinese and Japanese Literature," New York Times. 28 June 1966.

- Gruchy, John Walter de. (2003). Orienting Arthur Waley: Japonism, Orientalism, and the Creation of Japanese Literature in English. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. 1ISBN 0-8248-2567-5.

- Honey, David B. (2001). Incense at the Altar: Pioneering Sinologists and the Development of Classical Chinese Philology. American Oriental Series 86. New Haven, Connecticut: American Oriental Society. ISBN 0-940490-16-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johns, Francis A. (1968). A Bibliography of Arthur Waley. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- Johns, Francis A (1983). "Manifestations of Arthur Waley: Some Bibliographical and Other Notes" (PDF). The British Library Journal. 9 (2): 171–184.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morris, Ivan I. (1970). Madly Singing in the Mountains: An Appreciation and Anthology of Arthur Waley. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Robinson, Walter (1967). "Obituaries – Dr. Arthur Waley". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1–2): 59–61. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00125663. JSTOR 25202978.

- Simon, Walter (1967). "Obituary: Arthur Waley". Bulletin of the School of African and Oriental Studies, University of London. 30 (1): 268–71. JSTOR 611910.

- Spence, Jonathan. "Arthur Waley," in, Chinese Roundabout (New York: Norton, 1992 ISBN 0393033554), pp. 329–336.

- Waley, Alison. (1982). A Half of Two Lives. London: George Weidenfeld & Nicolson. (Reprinted in 1983 by McGraw-Hill.)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Arthur Waley |

- E. Bruce Brooks, "Arthur Waley" Warring States Project, University of Massachusetts.

- Waley's translation of The Way and Its Power

- Works by Arthur Waley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Arthur Waley at Internet Archive

- Works by Arthur Waley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Arthur Waley at Library of Congress Authorities, with 106 catalogue records