Srughna

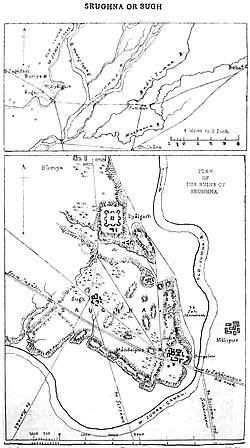

Srughna, also spelt Shrughna in Sanskrit, or Sughna, Sughana or Sugh in the spoken form,[1][2] was an ancient city or kingdom of India frequently referred to in early and medieval texts. It was visited by Chinese traveller, Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang) in the 7th century and was reported to be in ruins even then although the foundations still remained. Xuanzang described the kingdom as extending from the mountains to the north, to the Ganges river to the East, and with the Jumna river flowing through it.[1] He described the capital city on the west bank of the Jumna as possessing a large Buddhist vihara and a grand stupa dating to the time of the Mauryan emperor, Ashoka.[3] Srughna is identified with the Sugh Ancient Mound located in the village of Amadalpur Dayalgarh, in the Yamunanagar district of Haryana state of India.[4][5][6] To this day, the ancient Chaneti Buddhist Stupa, probably dating to the Mauryan period, stands in the area, about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) northwest of Sugh.[7]

Identification

Xuanzang saw several stupas, which commemorated the visit of the Buddha or enshrined the relics of Buddhist monks Sariputra and Maudgalyayana.[8] Alexander Cunningham identified the lost city with the village of Sugh (or Sugha) situated 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) from Yamunanagar in the state of Haryana.[9] The city probably lost its importance after the 7th century and the name survived in a localized form.[8] Panjab University's 1965 excavation found artifacts dating from 600 BCE to 300 CE, including grey ware and red ware pottery, coins, seals, animal remains, male and female terracotta figurines, animal terracotta figurines and miscellaneous terracotta objects such as flesh rubbers, crucibles, rattle, gamesmen, stamp, seal impression, discs, frames and wheels, balls, goldsmiths heating cup, an ear ornament grooved on the exterior and a broken figurine of a headless child with writing board in lap with sunga (187 BCE to 78 BCE) period alphabets.[8] Collection of these figurines belong to Sunga, Mauryan, Kushana, Gupta and medieval period.[8]

Srughna is regularly mentioned in Panini's Ashtadhyayi, Patanjali's Mahabhashya, the Divyavadana, the Mahabharata, the Mahamayuri, the Brihatsamhita of Varahamihira, etc. Tūrghna, another location mentioned in ancient literary texts, is considered synonymous with Srughna.[9][10]

The village of Sugh, with the nearby Sugh Ancient Mound, is now a well known archaeological site which has yielded a trove of coins. It was excavated by Cunningham in the 19th century. Suraj Bhan partially excavated the site in 1964–65.[9]

The original site of the Topra Kalan pillar of Ashoka is located about 18 kilometres (11 mi) to the west.[7] Ashoka's Rock edicts of Khalsi is also from the region, about 60 kilometres (37 mi) to the northeast.

Dhanabhuti, king of "Sugana"

It has been proposed that King Dhanabhuti, the main sponsor of the Buddhist stupa at Bharhut, came from Srughna or Sughana, and that Dhanabhuti was one of its important kings, who, besides building magnificent stupas in his capital city, also made some of the most important donations for the building of the toranas and railings at Bharhut.[11][12][13]

𑀅 𑀆 𑀇 𑀈 𑀉 𑀊 𑀏 𑀐 𑀑 𑀒 𑀅𑀁 𑀅𑀂

See also

Notes

- Cunningham, alexander (1871). Archeological Survey Of India Vol Ii. p. 227.

- Alexander Cunningham, Great Britain India Office (1879). The Stûpa of Bharhut: A Buddhist Monument Ornamented with Numerous ... W.H. Allen and Co. p. 3.

- Cunningham 1877, p. 34.

- "Ancient site of Sugh". HaryanaTourism.gov.in. Haryana Tourism Corporation Limited. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- Sharma, Shriv Kumar (8 June 2018). "DC orders probe into damage to ancient Sugh mound". The Tribune, India. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- "List of Protected Monuments in Haryana with notification no" (PDF). Archaeology Haryana. Department of Archaeology and Museums, Haryana. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- Gupta, Parmanand (1989). Geography from Ancient Indian Coins & Seals. Concept Publishing Company. p. 154. ISBN 9788170222484.

- Yamunanagar History, Gazatteer of Haryana: Yamunanagar.

- Handa 2000, pp. 517, 518.

- Bharadwaj 1980, p. 192:

"Tūrghna is apparently a scribal error for Srughna which was the region about Jagadhari with its head-quarters at the present village of Sugha situated on the Western Yumunā Canal at a distance of about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) to the east of Jagadhari town in district Ambala."

- "A local Buddhist kingdom in Punjab with Srughna, modern Sugh, near Jagadhri in the district of Ambala, as its capital city, and covering an area of about 1000 miles in circuit. Raja Dhanabhuti, the pre-eminent king of this royal family ruled from 240 B.C. to 210 B.C. This pious Buddhist king apart from building magnificent stupas in his capital city, also made munificent donations to the world famous Stupa of Bharhut" in Ahir, D. C. (1989). Buddhism in North India. Classics India Publications. p. 14. ISBN 9788185132099.

- Ahir, D. C. (1971). Buddhism In The Punjab Haryana And Himachal Pradesh. pp. 27–28.

- Kumar, Ajit (2014). "Bharhut Sculptures and their untenable Sunga Association". Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology. 2: 223‐241.

- Chhabra, B. Ch. (1970). Sugh Terracotta with Brahmi Barakhadi: appears in the Bulletin National Museum No. 2. New Delhi: National Museum.

- Chhabra, B.Ch. (1970). Sugh Terracotta with Brahmi Barakhadi: appears in the Bulletin National Museum No. 2. Bulletin National Museum No. 2.

References

- Cunningham, Alexander (1877). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum. Рипол Классик. ISBN 9785879911145.

- Handa, Devendra (2000). "Minuscule Silver Coins from Sugh". East and West. 50 (1/4): 515–521. JSTOR 29757464.

- Bharadwaj, O. P. (1980). "Gautama Buddha in Kurukṣetra". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 61 (1/4): 189–204. JSTOR 41691865.

External links

- Haryana tourism

- Article in Tribune India

- Ancient Geography of India by Alexander Cunningham (1871)

.jpg)