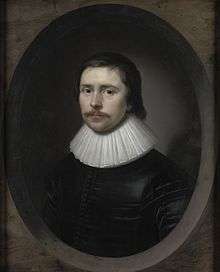

Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon

Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon (18 February 1609 – 9 December 1674), was an English statesman, diplomat and historian, who served as chief advisor to Charles I during the First English Civil War, and Lord Chancellor to his son from 1660 to 1667.

Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon | |

|---|---|

Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon | |

| Lord Chancellor | |

| In office 1660–1667 | |

| Monarch | Charles II |

| Member of the Long Parliament for Saltash | |

| In office November 1640 – August 1642 (disbarred) | |

| Member of the Short Parliament for Wootton Bassett | |

| In office April 1640 – May 1640 | |

| Chancellor, University of Oxford | |

| In office 1660–1667 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 February 1609 Dinton, Wiltshire |

| Died | 9 December 1674 (aged 65) Rouen, France |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey [1] |

| Nationality | English |

| Spouse(s) | Anne Ayliffe (1622-1629) Frances Aylesbury |

| Relations | Mary II (1662-1694) Queen Anne (1665-1714) |

| Children | Henry, Earl of Clarendon Laurence, Earl of Rochester Edward; James; Anne, Duchess of York; Frances Hyde |

| Parents | Henry Hyde; Mary Langford |

| Alma mater | Hertford College, Oxford |

| Occupation | Lawyer, politician and historian |

Unlike many contemporaries, Hyde largely avoided involvement in the political disputes of the 1630s, until elected to the Long Parliament in November 1640. Like many moderate Royalists, Hyde was a supporter of constitutional monarchy and the role of Parliament, but by 1642 felt its leaders were seeking too much power. He also believed in an Episcopalian Church of England, and opposed Puritan attempts to reform it.

As a result, he joined Charles in York, and served as his senior political advisor, but lost influence as the war progressed. Like his close friend Sir Ralph Hopton, devotion to the Church of England meant he opposed attempts to gain support from Scots Covenanters or Irish Catholics. In 1644, the Prince of Wales was given charge of the West Country, and Hyde became part of his Governing Council.

When the war ended in 1646, he went into exile, and largely avoided involvement in the Second English Civil War, which ended in the execution of Charles I. He served his son Charles II as a diplomat in Paris and Madrid, and refused to participate in the 1650 to 1651 Third English Civil War.

After Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, he was appointed Lord Chancellor, while his daughter Anne married the future James II, making him grandfather of two queens, Mary and Anne. These links brought him both power and enemies, and he was charged with treason after the 1665 to 1667 Second Anglo-Dutch War.

He left England to travel in Europe, where he remained until his death in 1674. His periods of exile were spent completing The History of the Rebellion, now regarded as one of the most significant histories of the period, covering the First English Civil War from 1642 to 1646. First written as a defence of Charles I, it was extensively revised after 1667, and became far more critical and frank, particularly in its assessments of his contemporaries.

Biographical details

Edward Hyde was born on 18 February 1609, at Dinton, Wiltshire, sixth of nine children, and third son of Henry Hyde, 1563 to 1634, and Mary Langford, 1578 to 1661. His father and two uncles qualified as lawyers; Henry became a country squire after his marriage, but Nicholas Hyde became Lord Chief Justice of England, while Lawrence was legal advisor to Anne of Denmark, wife of James I.[2]

His siblings included Anne (1597-?), Elizabeth (1599-?), Lawrence (1600-?), Henry (1601-1627), Mary (1603-?), Sibble (1605-?), Susanna (1607-?) and Nicholas (1610–1611).[3]

He married twice; in 1629, to Anne Ayliffe, who died six months later, then Frances Aylesbury in 1634. They had six surviving children; Henry (1638-1709), Laurence (1642-1711), Edward (1645-1665), James (1650-1681), Anne (1638-1671), and Frances. As mother of two future queens, Anne is the best remembered, but both Henry and Laurence had significant political careers, as did many of their cousins and relatives.

Educated at Gillingham School,[4] in 1622 he was admitted to Hertford College, Oxford, graduating in 1626. Originally intended for a career in the Church of England, the death of his elder brothers left him as his father's heir, and instead he entered the Middle Temple to study law.[5][6]

Career

Hyde later admitted he had limited interest in a legal career, declared that "next the immediate blessing and providence of God Almighty" he "owed all the little he knew and the little good that was in him to the friendships and conversation ... of the most excellent men in their several kinds that lived in that age."[7] These included Ben Jonson, John Selden, Edmund Waller, John Hales and especially Lord Falkland,[5] who became his best friend.[8] From their influence and the wide reading in which he indulged, he doubtless drew the solid learning and literary talent which afterwards distinguished him.[5] The diarist Samuel Pepys wrote thirty years later that he never knew anyone who could speak as well as Hyde. He was one of the most prominent members of the famous Great Tew Circle, a group of intellectuals who gathered at Lord Falkland's country house Great Tew, Oxfordshire.

On 22 November 1633 he was called to the bar and obtained quickly a good position and practice;[5] "you may have great joy of your son Ned" his uncle the Attorney General assured his father.[9] Both his marriages gained him influential friends, and in December 1634 he was made keeper of the writs and rolls of the Court of Common Pleas. His able conduct of the petition of the London merchants against Lord Treasurer Portland earned him the approval of Archbishop William Laud,[5] with whom he developed a friendship; this was perhaps surprising on the face of it, as Laud did not have a gift for making friends easily and his religious views were very different from Hyde's.[10] Hyde in his History explained that he admired Laud for his integrity and decency, and excused his notorious rudeness and bad temper, partly because of Laud's humble origins and partly because Hyde recognised the same weaknesses in himself.[10]

Political career

In April 1640, Hyde was elected Member of Parliament for both Shaftesbury and Wootton Bassett in the Short Parliament and chose to sit for Wootton Bassett. In November 1640 he was elected MP for Saltash in the Long Parliament,[11] Hyde was at first a moderate critic of King Charles I, but became more supportive of the king after he began to accept reforming bills from Parliament. Hyde opposed legislation restricting the power of the King to appoint his own advisors, viewing it unnecessary and an affront to the royal prerogative.[12] He gradually moved over towards the royalist side, championing the Church of England and opposing the execution of the Earl of Strafford, Charles's primary adviser. Following the Grand Remonstrance of 1641, Hyde became an informal adviser to the King. He left London about 20 May 1642 and rejoined the king at York.[13] In February 1643, Hyde was knighted and was officially appointed to the Privy Council; the following month he was made Chancellor of the Exchequer.[14]

Civil War

Despite his own previous opposition to the King, he found it hard to forgive anyone, even a friend, who fought for Parliament, and he severed many personal friendships as a result. With the possible exception of John Pym, he detested all the Parliamentary leaders, describing Oliver Cromwell as "a brave bad man" and John Hampden as a hypocrite, while Oliver St. John's "foxes and wolves" speech, in favour of the attainder of Strafford, he considered to be the depth of barbarism. His view of the conflict and of his opponents was undoubtedly coloured by the death of his best friend Lord Falkland at the First Battle of Newbury in September 1643. Hyde mourned his death, which he called "a loss most infamous and execrable to all posterity", to the end of his own life.[15]

He was equally severe in his judgments of those Royalist commanders who in his view had contributed to the King's defeat. Indeed, his harshest words of all (much harsher than those he used about Cromwell) were reserved for George Goring, Lord Goring, whose loyalty to Charles I was not seriously in doubt, whatever his other faults. Hyde described Goring as a man who would "without hesitation have broken any trust, or performed any act of treachery, to satisfy an ordinary passion or appetite, and in truth wanted nothing but industry (for he had wit and courage and understanding and ambition, uncontrolled by any fear of God or man) to have been as eminent and successful in the highest attempt at wickedness of any man in the age he lived in or before. Of all his qualifications dissimulation was his masterpiece; in which he so much excelled, that men were not ordinarily ashamed or out of countenance, in being but twice deceived by him".[16]

By 1645 his moderation, and the enmity of Henrietta Maria of France, had alienated Hyde from the King, and he was made guardian to the Prince of Wales, with whom he fled to Jersey in 1646.[17]

Despite their differences, he was horrified by the execution of the King, whom he always remembered with reverence. In his opinion the fatal flaw of Charles I, and of all the Stuart monarchs, was to let their own judgement, which was usually sound, become corrupted by the advice of their favourites, which was nearly always disastrous. Charles I he described as a man who had an excellent understanding but was not sufficiently confident of it himself, so that he often changed his opinion for a worse one, and "would follow the advice of a man who did not judge as well as himself".[18]

Hyde was not closely involved with Charles II's attempts to regain the throne between 1649 and 1651. It was during this period that Hyde began to write his great history of the Civil War. Hyde rejoined the exiled king in 1651 and was sent by him on an unsuccessful diplomatic mission to the Court of Spain and soon became his chief advisor. Charles appointed him Lord Chancellor on 13 January 1658.[19]

Restoration

On the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, he returned to England with the king and became even closer to the royal family through the marriage of his daughter Anne to the king's brother James, Duke of York, later King James II. Anne Hyde's two daughters were the monarchs Queen Mary II (1688–1694) and Queen Anne (1702–1714).

Contemporaries naturally assumed that Hyde had arranged the royal marriage of his daughter, but modern historians in general accept his repeated claims that he had no hand in it, and that indeed it came as an unwelcome shock to him. He is supposed to have told Anne that he would rather see her dead than to so disgrace her family.[20]

There were good reasons for Clarendon to oppose the marriage: he may have hoped to arrange a marriage for James with a foreign princess, and he was well aware that nobody regarded his daughter as a suitable royal match, a view which Clarendon, who was a rigid social conservative, entirely shared. On the personal level he seems to have disliked James, whose impulsive attempt to repudiate the marriage can hardly have endeared him to his father-in-law. Anne enforced the rules of etiquette governing such marriages with great strictness, and thus caused Clarendon and his wife some social embarrassment: as commoners, they were not permitted to sit down in Anne's presence, or to refer to her as their daughter in public (in theory, this was not allowed even in private). Above all, as Cardinal Mazarin remarked, the marriage was certain to damage Hyde's reputation as a politician, whether he was responsible for it or not.[20]

Chief Minister

On 3 November 1660, Hyde was raised to the peerage as Baron Hyde, of Hindon in the County of Wiltshire, and the 20 April the next year, at the coronation, he was created Viscount Cornbury and Earl of Clarendon.[21] He served as Chancellor of the University of Oxford from 1660 to 1667.[22]

As effective Chief Minister in the early years of the reign, he accepted the need to fulfill most of what had been promised in the Declaration of Breda, which he had partly drafted. In particular he worked hard to fulfill the promise of mercy to all the King's enemies, except the regicides, and this was largely achieved in the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion. Most other problems he was content to leave to Parliament, and in particular to the restored House of Lords; his speech welcoming the Lords' return shows his ingrained dislike of democracy.[23]

He played a key role in Charles' marriage to Catherine of Braganza, with ultimately harmful consequences to himself. Clarendon liked and admired the Queen and disapproved of the King's openly maintaining his mistresses. The King however resented any interference with his private life. Catherine's failure to bear children was also damaging to Clarendon, given the nearness of his own grandchildren to the throne, although it is most unlikely, as was alleged, that Clarendon had planned deliberately for Charles to marry an infertile bride.[24] He and Catherine were always on friendly terms, and one of his last letters was written to the Queen, thanking her for her kindness to his family.[25] As Lord Chancellor, it is commonly thought that Clarendon was the author of the "Clarendon Code", designed to preserve the supremacy of the Church of England. In reality he was not very heavily involved with its drafting and actually disapproved of much of its content. The "Great Tew Circle" of which he had been a leading member prided itself on tolerance and respect for religious differences. The code was thus merely named after him as chief minister.[26]

Downfall

In 1663, the Earl of Clarendon was one of eight Lords Proprietor given title to a huge tract of land in North America which became the Province of Carolina.[27]

Clarendon easily survived the first attempt to impeach him, in 1663. The charges made against him by George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol were so ludicrous that even Clarendon's worst enemies could not take them seriously, and Bristol greatly damaged his own career by making them.[28]

Quite unjustly Clarendon was accused of arranging the King's marriage to a woman he knew to be barren to secure the throne for the children of his daughter Anne, while the building of his palatial new mansion, Clarendon House in Piccadilly, was regarded, again unjustly, as evidence of corruption. He was also blamed for the Sale of Dunkirk, and for the fact that the Queen's dowry, Tangiers, proved to be nothing but a drain on the English finances. The windows of Clarendon House were broken, and a placard was fixed to the house blaming Clarendon for "Dunkirk, Tangiers and a barren Queen".[29] Clarendon began to fall out of favour with the King, whom he lectured frequently on his shortcomings, [30] and was also increasingly unpopular with the public. His open contempt for the King's leading mistress, Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland, a niece of his great friend Lady Morton, earned him her enmity, and she worked with the future members of the Cabal Ministry to destroy him.[31]

His authority was weakened by increasing ill-health, in particular attacks of gout and back pain [32] which became so severe that he was often incapacitated for months on end: Pepys records that early in 1665 he could scarcely stand, and was forced to lie on a couch during Council meetings. Even neutral courtiers began to see Clarendon as a liability: some of them apparently tried to persuade him to retire, and when that did not work, spread false reports that he was anxious to step down. In 1667, just after the fall of Clarendon, the upright Sir William Coventry admitted to Samuel Pepys that he had worked to bring Clarendon down (he was largely responsible for the false reports that Clarendon wanted to retire). This was not, as he stressed, because he had any doubts about Clarendon's desire to serve the King to the best of his ability, but because his dominance of policy-making made even the discussion, let alone the adoption of any alternative policy, impossible.[33] Clarendon in turn in his memoirs makes clear his bitterness against Coventry for what he regarded as his betrayal, which he contrasted with the loyalty which William's brother Henry Coventry showed to him throughout his life.[34]

Above all the military setbacks of the Second Anglo-Dutch War of 1665 to 1667, together with the disasters of the Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London, led to his downfall, and the successful Dutch Raid on the Medway in June 1667 was the final blow to his career.[35] It was in vain for Clarendon to plead that, unlike most of his accusers, he had opposed the war. Within weeks he was ordered by the King to surrender the Great Seal.[36] As he left Whitehall Barbara Villiers shouted abuse at him to which he replied with simple dignity "Madam, pray remember that if you live, you will also be old".[37] At almost the same time he suffered a great personal blow when his wife died after a short illness: in a will drawn up the previous year, he described her as "my dearly beloved wife, who hath accompanied and assisted me in all my distresses". [38] Clarendon was impeached by the House of Commons for blatant violations of Habeas Corpus, for having sent prisoners out of England to places like Jersey and holding them there without benefit of trial. He was forced to flee to France in November 1667. The King made it clear that he would not defend him, which betrayal of his old and loyal servant harmed Charles' reputation. Efforts to pass an Act of Attainder against him failed, but an Act providing for his banishment was passed in December and received the royal assent. Apart from Clarendon's son-in-law the Duke of York and Henry Coventry, few spoke in his defence. Clarendon was accompanied to France by his private chaplain and ally William Levett, later Dean of Bristol.[39]

Later years and exile

The rest of Clarendon's life was passed in exile. He left Calais for Rouen on 25 December, returning on 21 January 1668, visiting the baths of Bourbon in April, thence to Avignon in June, residing from July 1668 till June 1671 at Montpellier, whence he proceeded to Moulins and to Rouen again in May 1674. His sudden banishment entailed great personal hardships. His health at the time of his flight was much impaired, and on arriving at Calais he fell dangerously ill; and Louis XIV, anxious at this time to gain popularity in England, sent him peremptory and repeated orders to quit France. He suffered severely from gout, and during the greater part of his exile could not walk without the aid of two men. At Évreux, on 23 April 1668, he was the victim of a murderous assault by English sailors, who attributed to him the non-payment of their wages, and who were on the point of despatching him when he was rescued by the guard. For some time he was not allowed to see any of his children; even correspondence with him was rendered treasonable by the Act of Banishment; and it was not apparently until 1671, 1673, and 1674 that he received visits from his sons, the younger, Lawrence Hyde, being present with him at his death.[36]

He spent his exile working on his History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England, the classic account of the Civil War,[36] and for which he is chiefly remembered today. The sale proceeds from this book were instrumental in building the Clarendon Building and Clarendon Fund at Oxford University Press.[41]

He died in Rouen, France, on 9 December 1674. Shortly after his death, his body was returned to England, and he was buried in a private ceremony in Westminster Abbey on 4 January 1675.[42]

Portrayals in drama and fiction

Nigel Bruce played Sir Edward Hyde in the 1947 film The Exile, with Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. as Charles II.

In the film Cromwell, Clarendon (called only Sir Edward Hyde in the film), is portrayed by Nigel Stock as a sympathetic, conflicted man torn between Parliament and the king. He finally turns against Charles I altogether when the king pretends to accept Cromwell's terms of peace but secretly and treacherously plots to raise a Catholic army against Parliament and start a second civil war. Clarendon reluctantly, but bravely, gives testimony at the king's trial which is instrumental in condemning him to death.

In the 2003 BBC TV mini-series 'Charles II: The Power and The Passion, Clarendon was played by actor Ian McDiarmid. The series portrayed Clarendon (referred to as 'Sir Edward Hyde' throughout) as acting in a paternalistic fashion towards Charles II, something the king comes to dislike. It is also intimated that he had arranged the marriage of Charles and Catherine of Braganza already knowing that she was infertile so that his granddaughters through his daughter Anne Hyde (who had married the future James II) would eventually inherit the throne of England.

In the 2004 film Stage Beauty, starring Billy Crudup and Claire Danes, Clarendon (again referred to simply as Edward Hyde) is played by Edward Fox.

In fiction, Clarendon is a minor character in An Instance of the Fingerpost by Iain Pears, and he is also a recurring character in the Thomas Chaloner series of mystery novels by Susanna Gregory; both authors show him in a fairly sympathetic light.

Bibliography

- The history of Rebellion and Civil War in Ireland (1720)

- A Collection of several tracts of Edward, Earl of Clarendon, (1727)

- Religion and Policy, and the Countenance and Assistance each should give to the other, with a Survey of the Power and Jurisdiction of the Pope in the dominion of other Princes (Oxford 1811, 2 volumes)

- History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England: Begun in the Year 1641 by Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon (3 volumes) (1702-1704):

- Volume I, Part 1,

- Volume I, Part 2, new edition, 1807.

- Volume II, Part 1,

- Volume II, Part 2,

- Volume III, Part 1,

- Volume III, Part 2

- Essays, Moral and Entertaining by Clarendon (J. Sharpe, 1819)

- The Life of Edward Earl of Clarendon, Lord High Chancellor of England, and Chancellor of the University of Oxford Containing:

- I Life of Edward Earl of Clarendon: An Account of the Chancellor's Life from his Birth to the Restoration in 1660

- II Life of Edward Earl of Clarendon: A Continuation of the same, and of his History of the Grand Rebellion, from the Restoration to his Banishment in 1667

References

- "Edward Hyde & family". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Seaward, 2008 & OxfordDNBOnline.

- "Henry Hyde, MP". Geni.com. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Wagner 1958, p. .

- Chisholm 1911, p. 428.

- Firth 1891, p. 370.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 428 cites Life, i., 25

- Hyde 2009, p. 440.

- Ollard 1987, p. 20.

- Ollard 1987, p. 43.

- Willis 1750, pp. 229–239.

- Holmes 2007, p. 44.

- Firth 1891, p. 372 cites Life, ii. 14, 15; cf. Gardiner, x. 169.

- Firth 1891, p. 373 cites Life, ii. 77; Black, Oxford Docquets, p. 351.

- Hyde 2009, p. 182.

- Hyde 2009, p. 231.

- Firth 1891, p. 374.

- Hyde 2009, p. 335.

- Firth 1891, p. 376 cites Lister, i. p. 441.

- Ollard 1987, p. 226.

- Firth 1891, p. 378 cites Lister, ii. p. 81

- Firth 1891, p. 385 cites Kennett, Register, pp. 294, 310, 378; Macray, Annals of the Bodleian Library, ed. 1890, p. 462.

- Firth 1891, p. 382.

- Wheatley, Henry Benjamin Round about Piccadilly and Pall Mall (1870) Reprinted by Cambridge University Press 2011 p.85

- Ollard 1987, p. 341.

- Kenyon 1978, p. 215.

- Firth 1891, p. 379.

- Ollard 1987, p. 266.

- Wheatley p.85

- Ollard 1987, p. 276.

- Antonia Fraser King Charles Ii Mandarin Edition 1993 p.253

- Ollard 1987, p. 270.

- Diary of Samuel Pepys 2 September 1667

- Ollard goes so far as to say that Clarendon detested William Coventry- Clarendon and his Friends (1987) p.272

- Fraser, Antonia King Charles II p.251

- Chisholm 1911, p. 432.

- Fraser p.254

- Ollard 1987, p. 348.

- Clarendon & Rochester 1828, p. 285.

- Maclagan & Louda 1999, p. 27.

- Hugh Trevor-Roper, "Clarendon's 'History of the Rebellion'" History Today (1979) 29#2 pp 73–79

- Firth 1891, p. 384.

Sources

- Seaward, Paul (2008). Hyde, Edward, first earl of Clarendon (Online ed.). Oxford DNB.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clarendon, Henry Hyde, Earl of; Rochester, Laurence Hyde, Earl of (1828), The Correspondence of Henry Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, and His Brother Laurence Hyde, Earl of Rochester: With the Diary of Lord Clarendon from 1687 to 1690, Containing Minute Particulars of the Events Attending the Revolution and the Diary of Lord Rochester During His Embassy to Poland in 1676, H. Colburn, p. 285

- Firth, Charles Harding (1891), , in Lee, Sidney (ed.), Dictionary of National Biography, 28, London: Smith, Elder & Co, pp. 370–389 Contains a list of Clarendon's works.

- Lister, Life of Clarendon (2 volume ed.)

- Holmes, Clive (2007), Why was Charles I executed? ([Reprint.] ed.), London: Continuum, p. 44, ISBN 1847250246

- Maclagan, Michael; Louda, Jiří (1999), Line of Succession: Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe, London: Little, Brown & Co, p. 27, ISBN 1-85605-469-1

- Hyde, Edward (2009), The History of the Rebellion (Abridged ed.), Oxford University Press

- Kenyon, J.P. (1978), Stuart England, Allen Lane

- Ollard, Richard (1987), Clarendon and his Friends, Macmillans

- Wagner, A.F.H.V. (1958), Extract from: Gillingham Grammar School, Dorset – An Historical Account (First ed.), Gillingham Museum

- Willis, Browne (1750), Notitia Parliamentaria, Part II: A Series or Lists of the Representatives in the several Parliaments held from the Reformation 1541, to the Restoration 1660 ..., London, pp. 229–239

Attribution

Bibliography

- Brownley, Martine Watson. Clarendon & the Rhetoric of Historical Form (1985)

- Craik, Henry. The life of Edward, earl of Clarendon, lord high chancellor of England. (2 vol 1911) online vol 1 to 1660 and vol 2 from 1660

- Eustace, Timothy. "Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon," in Timothy Eustace, ed., Statesmen and Politicians of the Stuart Age (London, 1985). pp 157–78.

- Finlayson, Michael G. "Clarendon, Providence, and the Historical Revolution," Albion (1990) 22#4 pp 607–632 in JSTOR

- Firth, Charles H. "Clarendon's 'History of the Rebellion,"' Parts 1, II, III, English Historical Review vol 19, nos. 73-75 (1904)

- Harris, R. W. Clarendon and the English Revolution (London, 1983).

- Hill, Christopher. "Clarendon and Civil the War." History Today (1953) 3#10 pp 695–703.

- Hill, Christopher. "Lord Clarendon and the Puritan Revolution," in Hill, Puritanism and Revolution (London, 1958)

- MacGillivray, R.C. (1974). Restoration Historians and the English Civil War. Springer.

- Major, Philip ed. Clarendon Reconsidered: Law, Loyalty, Literature, 1640–1674 (2017) topical essays by scholars

- Miller, G. E. Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon (Boston, 1983), as historical writer

- Ollard, Richard. Clarendon and his Friends (Oxford UP, 1988), scholarly biography

- Richardson, R. C. The Debate on the English Revolution Revisited (London, 1988),

- Seaward, Paul. "Hyde, Edward, first earl of Clarendon (1609–1674)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004; online edn, Oct 2008 accessed 31 Aug 2017 doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14328

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh. "Clarendon's 'History of the Rebellion'" History Today (1979) 29#2 pp 73–79

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh. "Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon" in Trevor-Roper, From Counter-Reformation to Glorious Revolution (1992) pp 173–94 online

- Wormald, B. H. G. Clarendon, Politics, History & Religion, 1640-1660 (1951) online

- Wormald, B. H. G. "How Hyde Became a Royalist," Cambridge Historical Journal 8#2 (1945), pp. 65–92 in JSTOR

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon |

- "Henry Hyde, MP". Geni.com. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Edward Hyde & family". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Essays by Edward Hyde at Quotidiana.org

- Volume 2 of The Life of Edward Earl of Clarendon by Henry Craik from Project Gutenberg

- The Life of Edward, Earl of Clarendon, in which is included a Continuation of his History of the Grand Rebellion by Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon (Clarendon Press, 1827): Volume I, Volume II, Volume III

- Historical Enquiries Respecting the Character of Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon by George Agar-Ellis (1827)

| Parliament of England | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Parliament suspended since 1629 |

Member of Parliament for Shaftesbury 1640 With: William Whitaker |

Succeeded by William Whitaker Samuel Turner |

| Preceded by Parliament suspended since 1629 |

Member of Parliament for Wootton Bassett 1640 With: Sir Thomas Windebanke, 1st Baronet |

Succeeded by William Pleydell Edward Poole |

| Preceded by George Buller (MP) Francis Buller |

Member of Parliament for Saltash 1640–1642 With: George Buller (MP) |

Succeeded by John Thynne Henry Wills |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Sir John Colepeper |

Chancellor of the Exchequer 1643–1646 |

Succeeded by – |

| Preceded by Vacant – last held by Sir Edward Herbert |

Lord Chancellor 1658–1667 |

Succeeded by Orlando Bridgeman (Lord Keeper) |

| Preceded by The Lord Cottington (Lord High Treasurer) |

First Lord of the Treasury 1660 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Southampton (Lord High Treasurer) |

| Preceded by Interregnum |

Chancellor of the Exchequer 1660–1661 |

Succeeded by Sir Anthony Ashley-Cooper |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by Duke of Somerset |

Chancellor of the University of Oxford 1660–1667 |

Succeeded by Gilbert Sheldon |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by The Viscount Falkland |

Lord Lieutenant of Oxfordshire 1663–1668 |

Succeeded by The Viscount Saye and Sele |

| Vacant Title last held by The Duke of Ormonde |

Lord High Steward 1666 |

Vacant Title next held by The Lord Finch |

| Preceded by The Earl of Southampton |

Lord Lieutenant of Wiltshire 1667–1668 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Essex |

| Peerage of England | ||

| New creation | Earl of Clarendon 1661–1674 |

Succeeded by Henry Hyde |

| Baron Hyde 1660–1674 | ||

.svg.png)