Classical music of Birmingham

Medieval music

Although few records have survived to illustrate the culture of medieval Birmingham, there is evidence to suggest that the town supported a significant culture of religious music throughout the late Middle Ages. Chantries were established in 1330 and 1347 for priests to sing divine mass at the church of St Martin in the Bull Ring,[1] and the Guild of the Holy Cross, established in 1392, funded a further chantry of three priests and an organist,[2] who are also likely to have provided secular music for festivities in the Guild's hall on New Street.[3] Most remarkably the town had an organ builder by 1503 – a highly specialist and unusual trade for what was then a medium-sized market town.[4] None of these medieval musical institutions survived the Reformation of the 1530s.[5]

Although evidence of music in 16th and 17th century Birmingham is even more scant than for the earlier period, records survive to show the existence of a band of minstrels in the town in 1609, and at least one ballad was written in the town to commemorate the Battle of Birmingham of 1643 during the English Civil War.[5]

Music of the early Midlands Enlightenment

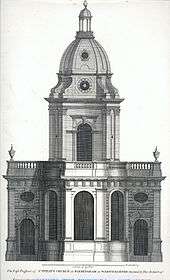

Birmingham's economy boomed in the years following the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, and over the course of the following century the town's huge growth in size and wealth came to be reflected in the self-conscious awakening of scientific and cultural activity now known as the Midlands Enlightenment.[6] The first outward sign of this coming cultural transformation was the opening of the baroque St Philip's Church in 1715, a building of exceptional sophistication for what was still a modestly-sized town.[7] Designed by the local architect Thomas Archer – the only English architect of his generation to have seen the work of Borromini in Rome at first hand[7] – St Philips' architectural pretensions were matched by its musical ambitions: it had a fine organ built by the organ builder Swarbruch, and the church and its organ began to attract gifted musicians to the town.[8]

.jpg)

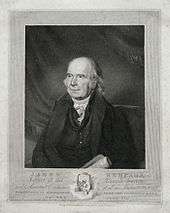

These religious musicians were also the originators of a transformation of the town's secular music life.[9] St Phillips' first organist was Barnabas Gunn, who was also notable as a composer, producing sonatas and solos for harpsichord, violin and cello, and Two Cantatas and Six Songs of 1736 that included George Frederick Handel among its subscribers.[10] Gunn promoted the first organised series of concerts in the town, at Holte Bridgman's Apollo Gardens, Sawyer's Assembly Rooms and the Moor Street Theatre, building a programme that featured leading international musicians from continental Europe, of a standard associated with the Three Choirs Festival or Chapel Royal, Windsor.[11] Michael Broome – who was responsible for training the choir at St Phillips from 1733 – also provided music lessons within the town, ran an extensive musical publishing business from Colmore Row, and was himself notable as a composer of psalms and other church music, works which were at the forefront the use of the treble part to carry the tune in Psalmody.[12] Broome was at the centre of an informal grouping of musicians and choristers from St Phillips that met to socialise and rehearse at Cooke's Coffee House, at the junction of Cherry Street and Cannon Street, from the 1730s.[13] This was formalised in 1762 into the Birmingham Musical and Amicable Society, the leading musical example of the myriad of private clubs and societies that formed the developing public sphere of enlightenment Birmingham,[14] by James Kempson, another prolific Birmingham publisher of church music,[15]

By the middle of the 18th century, Birmingham was supporting a vigorous and diverse musical calendar. Three-day festivals of oratorio, featuring 40-piece orchestras, choirs of 24 singers and nationally known soloists, are recorded taking place at the town's theatres from the 1740s.[16] Audiences "in their thousands" attended summer concerts of music by Handel and Arne from the 1740s at Birmingham's pleasure gardens – principally Holte Bridgman's Apollo Gardens in Deritend and Vauxhall Gardens in Duddeston.[17] During the winter the tradition of subscription concert series at Sawyer's Assembly Rooms in Old Square, started by Barnabas Gunn, was continued through the 1760s by John Eversman, his successor as organist at St Philips.[18] Ambitious series of concerts also took place at Packwood's in the Cherry Orchard.[14] By 1760 it was clear that Birmingham had supplanted Lichfield's traditional role as the centre of musical life in the English Midlands.[19]

Later Enlightenment and the birth of the music festivals

The music festivals that would thrust Victorian Birmingham to the forefront of European musical life had their roots in the private music societies of the Midlands Enlightenment, and in the economic difficulties faced by the town in the years following the end of the Seven Years' War.[20] The first music meeting to be held in Birmingham for a charitable purpose took place on Christmas Day 1766, when James Kempson organised members of the Birmingham Musical and Amicable Society to hold a one-day festival at St. Bartholemew's Chapel to aid "aged and distressed housekeepers" – a tradition that would continue annually until 1838.[21] The success of this, together with that of a three-day festival of oratorio held by Richard Hobbs and Capel Bond in 1767, led to Kempson's suggestion that large-scale musical performances "upon similar principles to those at St. Bartholemew's" might be used to raise money to support the Birmingham General Hospital, which was then lying half-built for lack of funds.[22] This resulted in the first three-day Birmingham Music Meeting, which was held in September 1768. Oratorios were performed at St Philip's and at the King Street Theatre to a "brilliant and crowded audience" including a "concourse of Nobility and Gentry from this and the neighbouring counties", with an orchestra of 25 conducted by Bond and a chorus of 45 from the Musical and Amicable Society trained by Kempson, raising a total of £200 (the equivalent of £10,000 in late 20th century terms) for the hospital.[23] A second Music Meeting like that of 1768 was held in 1774 to raise money for the building of St. Mary's Chapel in Whittal Street,[24] and with building work on the General Hospital again paused for lack of funds, in 1778 Kempson suggested a similar event be held for the joint benefit of the hospital and St Paul's Church in the Jewellery Quarter, where was newly installed as choirmaster.[24] Further festivals were held in 1780 and 1784, after which the trustees of the General Hospital resolved to establish the event as the regular Birmingham Triennial Music Festival, which would take place every three years with only two interruptions until 1914.[25]

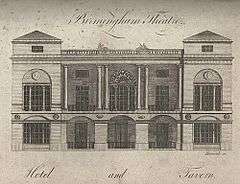

The 1778 Festival established the pattern of programming that would be maintained throughout the rest of the century, with a series of oratorios dominated by the work of Handel being presented at St Philip's during the mornings and "Grand Miscellaneous Concerts", with a more varied repertoire including works by composers such as Haydn, Purcell and Abel, taking place at the New Street Theatre in the evening.[26] The festival attracted soloists with national or – increasingly – European profiles,[27] with performers in the late 18th century including the sopranos Charlotte Brent, Gertrud Elisabeth Mara and Elizabeth Billington;[28] the instrumentalists Wilhelm Cramer, Giacobbe Cervetto, John Crosdill, John Mahon and Robert Lindley;[29] and the conductors Thomas Greatorex, William Crotch and Samuel Wesley.[30] By 1790 the Birmingham Festival had expanded to occupy the Royal Hotel as well as the New Street Theatre and St Philip's and had become a major meeting point for the aristocracy of the English Midlands, being attended by the Earl of Aylesford, the Earl of Warwick, Viscount Dudley and Ward, Sir Robert Lawley and the High Sheriff of Warwickshire among others.[31] Receipts from the festivals increased steadily, and by 1805 the sum donated to the hospital was "by far the largest sum ever raised that way outside the metropolis"[32]

.jpg)

Away from the festivals the standard of musical performance in Birmingham increased rapidly in the decades following 1760, particularly among the town's own musicians, further reducing the dependence of Birmingham upon older musical centres.[33] By 1769 Birmingham was developing its own orchestral resources, with concerts of "vocal and instrumental music" being advertised with "the instrumental by the best performers of the town".[34] After 1772 the Royal Hotel in Temple Row formed the town's main venue for concerts and polite social gatherings, hosting dancing assemblies and subscription concerts by the Birmingham Dilettanti Musical Society under Jeremiah Clarke.[33] These combined after 1788 to provide a year-round programme featuring six grand concerts and balls during the winter months, interspersed with dancing assemblies and complemented by a second series of monthly concerts during the summer.[33] Regular operas were performed at the King Street Theatre and from 1778 at the New Street Theatre.[35] Highly technical advertisements for concerts in the Birmingham Gazette from the 1790s suggest that by then the Birmingham audience was well informed and maintained a high level of musically literacy.[36] Notable late 18th century Birmingham composers included John Alcock, who wrote numerous religious compositions while organist at Sutton Coldfield,[14] and Joseph Harris, who was born in Birmingham and returned as organist of St Martin in the Bull Ring, and is thought to be the composer of the one act pastoral Menalcas,[10] in addition to two books of songs and six keyboard quartets that are notable for giving melodic parts to the strings, and for having slow movements of an unusually ornamental style.[37]

Regency and early Victorian music

The first half of the 19th century saw the profile of Birmingham's musical culture, and particularly that of the Birmingham Music Festival, gradually establish first a national and then an international importance. For all its success, during the 18th century the Birmingham Festival had been primarily a local institution, part of a circuit of provincial festivals that included similar events in Liverpool, Chester, Salisbury and Norwich.[38] By the 1820s however the Birmingham festival had surpassed not just its previous peers but also the older and more established Three Choirs Festival in status,[39] and it could be commented that Birmingham had "taken a lead among our numerous provincial festivals ... they give an impulse, and impart a tone and direction, to all other undertakings of a similar kind."[40] By the middle of the century the Birmingham Festival was well established as one of the leading events in the calendar of Western classical music, leading taste in London and beyond.[41] Of the festivals of the 1850s it was later commented that "Undoubtedly these gatherings were the best of their kind in the whole musical world, for not only were the performances unequalled, but the Committee by their generosity offered to the composers of all nations the opportunity of introducing their compositions to the world in a manner of exceptional excellence, thus giving to the town the honour of being the birthplace of some of the greatest works ever composed."[42] By 1852 the American critic Lowell Mason could write from New York City: "The Birmingham Festival seems to move the whole musical kingdom. It brings together the best talent that can be found, and the works of the greatest masters are performed, under circumstances more advantageous than are elsewhere to be found in the world".[43]

Later Victorian music

The Birmingham Triennial Music Festival took place from 1784 to 1912 and was considered the grandest of its kind throughout Britain. Music was written for the festival by Mendelssohn, Gounod, Sullivan, Dvořák, Bantock and most notably Elgar, who wrote four of his most famous choral pieces for Birmingham.

Albert William Ketèlbey was born in Alma Street, Aston on 9 August 1875, the son of a teacher at the Vittoria School of Art. Ketèlbey attended the Trinity College of Music, where he beat the runner-up, Gustav Holst, for a musical scholarship.

John Joubert, the distinguished composer of choral works, joined the University of Birmingham's Music Department as senior lecturer in 1962, retiring in 1986 to concentrate on his music. During that time he had written the second of his operas and was working on his third, as well as completing a number of orchestral and chamber works. In 1995 the orchestra of Birmingham Composers Forum put on what was only the second UK performance of his Second Symphony, dating from 1970.[44]

Contemporary classical music

The internationally renowned City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra's home venue is Symphony Hall, which in acoustic terms is widely considered to be one of the greatest concert halls of the 20th century and also hosts concerts by many visiting orchestras.

Other professional orchestras based in the city include the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, a chamber orchestra specialising in modern music with some world premieres; the Royal Ballet Sinfonia, who give concert performances under music director Barry Wordsworth in addition to playing for the Birmingham Royal Ballet; and Ex Cathedra, one of the country's oldest and most respected early-music and Baroque period instrument ensembles.

Birmingham is an important centre for musical education as the home of the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, founded in 1859. The Royal College of Organists is based in Digbeth. Birmingham City Council appoint the Birmingham City Organist to provide a free series of weekly public organ recitals.

The Birmingham Royal Ballet resides in the city as does the Elmhurst School for Dance, based in Edgbaston, and which claims to be the world's oldest vocational dance school.

Birmingham's professional opera company – the Birmingham Opera Company – specialises in staging innovative performances in unusual venues (in 2005 it performed Monteverdi's Il Ritorno d'Ulisse in Patria in a burnt-out ice rink in the Chinese Quarter). Its artistic director, Graham Vick, has also directed at La Scala, Milan, the Metropolitan Opera in New York and the Royal Opera House in London.

Visiting opera companies such as Opera North and Welsh National Opera perform regularly at the Hippodrome.

Birmingham's other principal classical music venues include The National Indoor Arena (NIA), CBSO Centre, The Bradshaw Hall at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, the Barber Concert Hall at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts and Birmingham Town Hall. Concerts also regularly take place in churches around the city including St Phillips Cathedral, St Paul's in the Jewellery Quarter, St Alban's in Highgate and The Oratory on the Hagley Road.

References

- Handford 2006, p. 7.

- Sutcliffe Smith 1945, p. 6.

- Handford 2006, pp. 7-9.

- Handford 2006, p. 9.

- Handford 2006, p. 10.

- Money 1977, p. 81.

- Foster, Andy (2005), Birmingham, Pevsner Architectural Guides, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p. 40, ISBN 0300107315, retrieved 2013-02-19

- Handford 2006, p. 12.

- Handford 2006, p. 19.

- Handford 2006, p. 13.

- Handford 2006, pp. 14-15.

- Handford 2006, p. 15-18.

- Handford 2006, pp. 19, 22.

- Sutcliffe Smith 1945, p. 13.

- Handford 2006, p. 22.

- Handford 2006, pp. 22-23.

- Handford 2006, p. 30.

- Handford 2006, p. 38.

- Money 1977, pp. 82-83.

- Handford 2006, p. 24.

- Handford 2006, pp. 24-25.

- Handford 2006, p. 25.

- Handford 2006, pp. 26-27.

- Handford 2006, p. 46.

- Drummond 2011, p. 23.

- Handford 2006, pp. 49-50.

- Handford 2006, p. 52.

- Handford 2006, pp. 52-54.

- Handford 2006, pp. 63-66.

- Handford 2006, pp. 67-69.

- Money 1977, p. 85.

- Drummond 2011, p. 24.

- Money 1977, p. 83.

- Sutcliffe Smith 1945, pp. 17-18.

- Handford 2006, p. 37.

- Money 1977, pp. 83-84.

- Loewenberg, Alfred, "Harris, Joseph", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 2013-02-03

- Drummond 2011, p. 33.

- Drummond 2011, p. 39.

- Drummond 2011, p. 41.

- Handford 2006, pp. 85, 103.

- Handford 2006, p. 106.

- Handford 2006, p. 108.

- ["Inspired by Massacre of Innocents", Birmingham Post, 26 October 1995]

Bibliography

- Drummond, Pippa (2011), The Provincial Music Festival in England, 1784-1914, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 1409432815, retrieved 2013-03-02

- Handford, Margaret (2006), Sounds Unlikely: Music in Birmingham, Studley: Brewin Books, ISBN 1858582873

- Money, John (1977), Experience and identity: Birmingham and the West Midlands, 1760–1800, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-0672-2, retrieved 16 June 2009

- Sutcliffe Smith, Joseph (1945), The story of music in Birmingham, Birmingham: Cornish Bros., OCLC 4184921

External links

- Birmingham Music Archive Celebrating, Preserving and Sharing Birmingham's Music Heritage.

- Brum Beat West Midlands Pop Groups of the 1960s

- Bachtrack Birmingham Classical music concerts and concert reviews in Birmingham