Hair

Hair is a protein filament that grows from follicles found in the dermis. Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals. The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick terminal and fine vellus hair. Most common interest in hair is focused on hair growth, hair types, and hair care, but hair is also an important biomaterial primarily composed of protein, notably alpha-keratin.

| Hair | |

|---|---|

Cross section of a hair strand | |

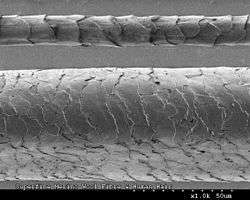

Scanning electron microscopy image of Merino wool (top) and human hair (bottom) showing keratin scales. | |

| Details | |

| System | Integumentary system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | capillum |

| MeSH | D006197 |

| TA | A16.0.00.014 |

| TH | H3.12.00.3.02001 |

| FMA | 53667 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Attitudes towards different forms of hair, such as hairstyles and hair removal, vary widely across different cultures and historical periods, but it is often used to indicate a person's personal beliefs or social position, such as their age, sex, or religion.[1]

Overview

The word "hair" usually refers to two distinct structures:

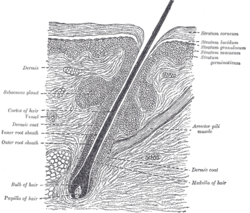

- the part beneath the skin, called the hair follicle, or, when pulled from the skin, the bulb or root. This organ is located in the dermis and maintains stem cells, which not only re-grow the hair after it falls out, but also are recruited to regrow skin after a wound.[2]

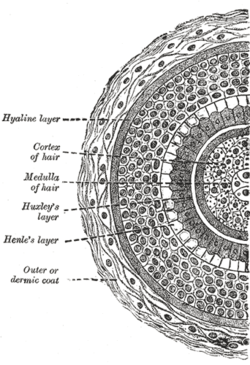

- the shaft, which is the hard filamentous part that extends above the skin surface. A cross section of the hair shaft may be divided roughly into three zones.

Hair fibers have a structure consisting of several layers, starting from the outside:

Description

Each strand of hair is made up of the medulla, cortex, and cuticle.[4] The innermost region, the medulla, is not always present and is an open, unstructured region.[5] The highly structural and organized cortex, or second of three layers of the hair, is the primary source of mechanical strength and water uptake. The cortex contains melanin, which colors the fiber based on the number, distribution and types of melanin granules. The shape of the follicle determines the shape of the cortex, and the shape of the fiber is related to how straight or curly the hair is. People with straight hair have round hair fibers. Oval and other shaped fibers are generally more wavy or curly. The cuticle is the outer covering. Its complex structure slides as the hair swells and is covered with a single molecular layer of lipid that makes the hair repel water.[4] The diameter of human hair varies from 0.017 to 0.18 millimeters (0.00067 to 0.00709 in).[6] There are two million small, tubular glands and sweat glands that produce watery fluids that cool the body by evaporation. The glands at the opening of the hair produce a fatty secretion that lubricates the hair.[7]

Hair growth begins inside the hair follicle. The only "living" portion of the hair is found in the follicle. The hair that is visible is the hair shaft, which exhibits no biochemical activity and is considered "dead". The base of a hair's root (the "bulb") contains the cells that produce the hair shaft.[8] Other structures of the hair follicle include the oil producing sebaceous gland which lubricates the hair and the arrector pili muscles, which are responsible for causing hairs to stand up. In humans with little body hair, the effect results in goose bumps.

Root of the hair

| Root of the hair | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | radix pili |

| MeSH | D006197 |

| TA | A16.0.00.014 |

| TH | H3.12.00.3.02001 |

| FMA | 53667 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The root of the hair ends in an enlargement, the hair bulb, which is whiter in color and softer in texture than the shaft, and is lodged in a follicular involution of the epidermis called the hair follicle. The bulb of hair consists of fibrous connective tissue, glassy membrane, external root sheath, internal root sheath composed of epithelium stratum (Henle's layer) and granular stratum (Huxley's layer), cuticle, cortex and medulla.[9]

Natural color

All natural hair colors are the result of two types of hair pigments. Both of these pigments are melanin types, produced inside the hair follicle and packed into granules found in the fibers. Eumelanin is the dominant pigment in brown hair and black hair, while pheomelanin is dominant in red hair. Blond hair is the result of having little pigmentation in the hair strand. Gray hair occurs when melanin production decreases or stops, while poliosis is hair (and often the skin to which the hair is attached), typically in spots, that never possessed melanin at all in the first place, or ceased for natural genetic reasons, generally, in the first years of life.

Human hair growth

Hair grows everywhere on the external body except for mucus membranes and glabrous skin, such as that found on the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, and lips.

Hair follows a specific growth cycle with three distinct and concurrent phases: anagen, catagen, and telogen phases; all three occur simultaneously throughout the body. Each has specific characteristics that determine the length of the hair.

The body has different types of hair, including vellus hair and androgenic hair, each with its own type of cellular construction. The different construction gives the hair unique characteristics, serving specific purposes, mainly, warmth and protection.

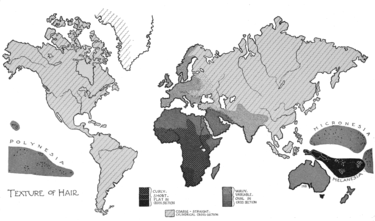

Texture

Hair exists in a variety of textures. Three main aspects of hair texture are the curl pattern, volume, and consistency. The derivations of hair texture are not fully understood. All mammalian hair is composed of keratin, so the make-up of hair follicles is not the source of varying hair patterns. There are a range of theories pertaining to the curl patterns of hair. Scientists have come to believe that the shape of the hair shaft has an effect on the curliness of the individual's hair. A very round shaft allows for fewer disulfide bonds to be present in the hair strand. This means the bonds present are directly in line with one another, resulting in straight hair.[10]

The flatter the hair shaft becomes, the curlier hair gets, because the shape allows more cysteines to become compacted together resulting in a bent shape that, with every additional disulfide bond, becomes curlier in form.[10] As the hair follicle shape determines curl pattern, the hair follicle size determines thickness. While the circumference of the hair follicle expands, so does the thickness of the hair follicle. An individual's hair volume, as a result, can be thin, normal, or thick. The consistency of hair can almost always be grouped into three categories: fine, medium, and coarse. This trait is determined by the hair follicle volume and the condition of the strand.[11] Fine hair has the smallest circumference, coarse hair has the largest circumference, and medium hair is anywhere between the other two.[11] Coarse hair has a more open cuticle than thin or medium hair causing it to be the most porous.[11]

Classification systems

There are various systems that people use to classify their curl patterns. Being knowledgeable of an individual's hair type is a good start to knowing how to take care of one's hair. There is not just one method to discovering one's hair type. Additionally it is possible, and quite normal to have more than one kind of hair type, for instance having a mixture of both type 3a & 3b curls.

- Andre Walker system

The Andre Walker Hair Typing System is the most widely used system to classify hair. The system was created by the hairstylist of Oprah Winfrey, Andre Walker. According to this system there are four types of hair: straight, wavy, curly, kinky.

- Type 1 is straight hair, which reflects the most sheen and also the most resilient hair of all of the hair types. It is hard to damage and immensely difficult to curl this hair texture. Because the sebum easily spreads from the scalp to the ends without curls or kinks to interrupt its path, it is the most oily hair texture of all.

- Type 2 is wavy hair, whose texture and sheen ranges somewhere between straight and curly hair. Wavy hair is also more likely to become frizzy than straight hair. While type A waves can easily alternate between straight and curly styles, type B and C Wavy hair is resistant to styling.

- Type 3 is curly hair known to have an S-shape. The curl pattern may resemble a lowercase "s", uppercase "S", or sometimes an uppercase "Z" or lowercase "z". This hair type is usually voluminous, "climate dependent (humidity = frizz), and damage-prone." Lack of proper care causes less defined curls.

- Type 4 is kinky hair, which features a tightly coiled curl pattern (or no discernible curl pattern at all) that is often fragile with a very high density. This type of hair shrinks when wet and because it has fewer cuticle layers than other hair types it is more susceptible to damage.

| Type 1: Straight | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1a | Straight (Fine/Thin) | Hair tends to be very soft, thin, shiny, oily, poor at holding curls, difficult to damage. |

| 1b | Straight (Medium) | Hair characterized by volume and body. |

| 1c | Straight (Coarse) | Hair tends to be bone-straight, coarse, difficult to curl. |

| Type 2: Wavy | ||

| 2a | Wavy (Fine/Thin) | Hair has definite "S" pattern, can easily be straightened or curled, usually receptive to a variety of styles. |

| 2b | Wavy (Medium) | Can tend to be frizzy and a little resistant to styling. |

| 2c | Wavy (Coarse) | Fairly coarse, frizzy or very frizzy with thicker waves, often more resistant to styling. |

| Type 3: Curly | ||

| 3a | Curly (Loose) | Presents a definite "S" pattern, tends to combine thickness, volume, and/or frizziness. |

| 3b | Curly (Tight) | Presents a definite "S" pattern, curls ranging from spirals to spiral-shaped corkscrew |

| Type 4: Kinky | ||

| 4a | Kinky (Soft) | Hair tends to be very wiry and fragile, tightly coiled and can feature curly patterning. |

| 4b | Kinky (Wiry) | As 4a but with less defined pattern of curls, looks more like a "Z" with sharp angles |

- FIA system

This is a method which classifies the hair by curl pattern, hair-strand thickness and overall hair volume.

|

Curliness | ||

|---|---|---|

| Straight | ||

| 1a | Stick-straight. | |

| 1b | Straight but with a slight body wave adding some volume. | |

| 1c | Straight with body wave and one or two visible S-waves (e.g. at nape of neck or temples). | |

| Wavy | ||

| 2a | Loose with stretched S-waves throughout. | |

| 2b | Shorter with more distinct S-waves (resembling e.g. braided damp hair). | |

| 2c | Distinct S-waves, some spiral curling. | |

| Curly | ||

| 3a | Big, loose spiral curls. | |

| 3b | Bouncy ringlets. | |

| 3c | Tight corkscrews. | |

| Very ("Really") curly | ||

| 4a | Tightly coiled S-curls. | |

| 4b | Z-patterned (tightly coiled, sharply angled) | |

| 4c | Mostly Z-patterned (tightly kinked, less definition) | |

|

Strands | ||

| F | Fine

Thin strands that sometimes are almost translucent when held up to the light. | |

| M | Medium

Strands are neither fine nor coarse. | |

| C | Coarse

Thick strands whose shed strands usually are easily identified. | |

| Volume by circumference of full-hair ponytail | ||

| i | Thin | circumference less than 2 inches (5 centimetres) |

| ii | Normal | ... from 2 to 4 inches (5 to 10 centimetres) |

| iii | Thick | ... more than 4 inches (10 centimetres) |

Functions

Many mammals have fur and other hairs that serve different functions. Hair provides thermal regulation and camouflage for many animals; for others it provides signals to other animals such as warnings, mating, or other communicative displays; and for some animals hair provides defensive functions and, rarely, even offensive protection. Hair also has a sensory function, extending the sense of touch beyond the surface of the skin. Guard hairs give warnings that may trigger a recoiling reaction.

Warmth

While humans have developed clothing and other means of keeping warm, the hair found on the head serves primarily as a source of heat insulation and cooling (when sweat evaporates from soaked hair) as well as protection from ultra-violet radiation exposure. The function of hair in other locations is debated. Hats and coats are still required while doing outdoor activities in cold weather to prevent frostbite and hypothermia, but the hair on the human body does help to keep the internal temperature regulated. When the body is too cold, the arrector pili muscles found attached to hair follicles stand up, causing the hair in these follicles to do the same. These hairs then form a heat-trapping layer above the epidermis. This process is formally called piloerection, derived from the Latin words 'pilus' ('hair') and 'erectio' ('rising up'), but is more commonly known as 'having goose bumps' in English.[12] This is more effective in other mammals whose fur fluffs up to create air pockets between hairs that insulate the body from the cold. The opposite actions occur when the body is too warm; the arrector muscles make the hair lie flat on the skin which allows heat to leave.

Protection

In some mammals, such as hedgehogs and porcupines, the hairs have been modified into hard spines or quills. These are covered with thick plates of keratin and serve as protection against predators. Thick hair such as that of the lion's mane and grizzly bear's fur do offer some protection from physical damages such as bites and scratches.

Touch sense

Displacement and vibration of hair shafts are detected by hair follicle nerve receptors and nerve receptors within the skin. Hairs can sense movements of air as well as touch by physical objects and they provide sensory awareness of the presence of ectoparasites.[13] Some hairs, such as eyelashes, are especially sensitive to the presence of potentially harmful matter.[14][15][16][17]

Eyebrows and eyelashes

The eyebrows provide moderate protection to the eyes from dirt, sweat and rain. They also play a key role in non-verbal communication by displaying emotions such as sadness, anger, surprise and excitement. In many other mammals, they contain much longer, whisker-like hairs that act as tactile sensors.

The eyelash grows at the edges of the eyelid and protects the eye from dirt. The eyelash is to humans, camels, horses, ostriches etc., what whiskers are to cats; they are used to sense when dirt, dust, or any other potentially harmful object is too close to the eye.[18] The eye reflexively closes as a result of this sensation.

Evolution

Hair has its origins in the common ancestor of mammals, the synapsids, about 300 million years ago. It is currently unknown at what stage the synapsids acquired mammalian characteristics such as body hair and mammary glands, as the fossils only rarely provide direct evidence for soft tissues. Skin impression of the belly and lower tail of a pelycosaur, possibly Haptodus shows the basal synapsid stock bore transverse rows of rectangular scutes, similar to those of a modern crocodile.[19] An exceptionally well-preserved skull of Estemmenosuchus, a therapsid from the Upper Permian, shows smooth, hairless skin with what appears to be glandular depressions,[20] though as a semi-aquatic species it might not have been particularly useful to determine the integument of terrestrial species. The oldest undisputed known fossils showing unambiguous imprints of hair are the Callovian (late middle Jurassic) Castorocauda and several contemporary haramiyidans, both near-mammal cynodonts.[21][22][23] More recently, studies on terminal Permian Russian coprolites may suggest that non-mammalian synapsids from that era had fur.[24] If this is the case, these are the oldest hair remnants known, showcasing that fur occurred as far back as the latest Paleozoic.

Some modern mammals have a special gland in front of each orbit used to preen the fur, called the harderian gland. Imprints of this structure are found in the skull of the small early mammals like Morganucodon, but not in their cynodont ancestors like Thrinaxodon.[25]

The hairs of the fur in modern animals are all connected to nerves, and so the fur also serves as a transmitter for sensory input. Fur could have evolved from sensory hair (whiskers). The signals from this sensory apparatus is interpreted in the neocortex, a chapter of the brain that expanded markedly in animals like Morganucodon and Hadrocodium.[26] The more advanced therapsids could have had a combination of naked skin, whiskers, and scutes. A full pelage likely did not evolve until the therapsid-mammal transition.[27] The more advanced, smaller therapsids could have had a combination of hair and scutes, a combination still found in some modern mammals, such as rodents and the opossum.[28]

The high interspecific variability of the size, color, and microstructure of hair often enables the identification of species based on single hair filaments.[29][30]

In varying degrees most mammals have some skin areas without natural hair. On the human body, glabrous skin is found on the ventral portion of the fingers, palms, soles of feet and lips, which are all parts of the body most closely associated with interacting with the world around us,[31] as are the labia minora and glans penis.[32] There are four main types of mechanoreceptors in the glabrous skin of humans: Pacinian corpuscles, Meissner's corpuscles, Merkel's discs, and Ruffini corpuscles.

The naked mole-rat (Heterocephalus glaber) has evolved skin lacking in general, pelagic hair covering, yet has retained long, very sparsely scattered tactile hairs over its body.[31] Glabrousness is a trait that may be associated with neoteny.[33]

Human hairlessness

The general hairlessness of humans in comparison to related species may be due to loss of functionality in the pseudogene KRTHAP1 (which helps produce keratin) in the human lineage about 240,000 years ago.[34] On an individual basis, mutations in the gene HR can lead to complete hair loss, though this is not typical in humans.[35] Humans may also lose their hair as a result of hormonal imbalance due to drugs or pregnancy.[36]

In order to comprehend why humans are essentially hairless, it is essential to understand that mammalian body hair is not merely an aesthetic characteristic; it protects the skin from wounds, bites, heat, cold, and UV radiation.[37] Additionally, it can be used as a communication tool and as a camouflage.[38] To this end, it can be concluded that benefits stemming from the loss of human body hair must be great enough to outweigh the loss of these protective functions by nakedness.[39]

Humans are the only primate species that have undergone significant hair loss and of the approximately 5000 extant species of mammal, only a handful are effectively hairless. This list includes elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, walruses, some species of pigs, whales and other cetaceans, and naked mole rats.[38] Most mammals have light skin that is covered by fur, and biologists believe that early human ancestors started out this way also. Dark skin probably evolved after humans lost their body fur, because the naked skin was vulnerable to the strong UV radiation as explained in the Out of Africa hypothesis. Therefore, evidence of the time when human skin darkened has been used to date the loss of human body hair, assuming that the dark skin was needed after the fur was gone.

It was expected that dating the split of the ancestral human louse into two species, the head louse and the pubic louse, would date the loss of body hair in human ancestors. However, it turned out that the human pubic louse does not descend from the ancestral human louse, but from the gorilla louse, diverging 3.3 million years ago. This suggests that humans had lost body hair (but retained head hair) and developed thick pubic hair prior to this date, were living in or close to the forest where gorillas lived, and acquired pubic lice from butchering gorillas or sleeping in their nests.[40][41] The evolution of the body louse from the head louse, on the other hand, places the date of clothing much later, some 100,000 years ago.[42][43]

The sweat glands in humans could have evolved to spread from the hands and feet as the body hair changed, or the hair change could have occurred to facilitate sweating. Horses and humans are two of the few animals capable of sweating on most of their body, yet horses are larger and still have fully developed fur. In humans, the skin hairs lie flat in hot conditions, as the arrector pili muscles relax, preventing heat from being trapped by a layer of still air between the hairs, and increasing heat loss by convection.

Another hypothesis for the thick body hair on humans proposes that Fisherian runaway sexual selection played a role (as well as in the selection of long head hair), (see types of hair and vellus hair), as well as a much larger role of testosterone in men. Sexual selection is the only theory thus far that explains the sexual dimorphism seen in the hair patterns of men and women. On average, men have more body hair than women. Males have more terminal hair, especially on the face, chest, abdomen, and back, and females have more vellus hair, which is less visible. The halting of hair development at a juvenile stage, vellus hair, would also be consistent with the neoteny evident in humans, especially in females, and thus they could have occurred at the same time.[44] This theory, however, has significant holdings in today's cultural norms. There is no evidence that sexual selection would proceed to such a drastic extent over a million years ago when a full, lush coat of hair would most likely indicate health and would therefore be more likely to be selected for, not against, and not all human populations today have sexual dimorphism in body hair.

A further hypothesis is that human hair was reduced in response to ectoparasites.[45][46] The "ectoparasite" explanation of modern human nakedness is based on the principle that a hairless primate would harbor fewer parasites. When our ancestors adopted group-dwelling social arrangements roughly 1.8 mya, ectoparasite loads increased dramatically. Early humans became the only one of the 193 primate species to have fleas, which can be attributed to the close living arrangements of large groups of individuals. While primate species have communal sleeping arrangements, these groups are always on the move and thus are less likely to harbor ectoparasites. Because of this, selection pressure for early humans would favor decreasing body hair because those with thick coats would have more lethal-disease-carrying ectoparasites and would thereby have lower fitness.

Another view is proposed by James Giles, who attempts to explain hairlessness as evolved from the relationship between mother and child, and as a consequence of bipedalism. Giles also connects romantic love to hairlessness.[47][48]

Another hypothesis is that humans' use of fire caused or initiated the reduction in human hair.[49]

Evolutionary variation

Evolutionary biologists suggest that the genus Homo arose in East Africa approximately 2.5 million years ago.[50] They devised new hunting techniques.[50] The higher protein diet led to the evolution of larger body and brain sizes.[50] Jablonski[50] postulates that increasing body size, in conjunction with intensified hunting during the day at the equator, gave rise to a greater need to rapidly expel heat. As a result, humans evolved the ability to sweat: a process which was facilitated by the loss of body hair.[50]

Another factor in human evolution that also occurred in the prehistoric past was a preferential selection for neoteny, particularly in females. The idea that adult humans exhibit certain neotenous (juvenile) features, not evinced in the great apes, is about a century old. Louis Bolk made a long list of such traits,[51] and Stephen Jay Gould published a short list in Ontogeny and Phylogeny.[52] In addition, paedomorphic characteristics in women are often acknowledged as desirable by men in developed countries.[53] For instance, vellus hair is a juvenile characteristic. However, while men develop longer, coarser, thicker, and darker terminal hair through sexual differentiation, women do not, leaving their vellus hair visible.

Texture

Curly hair

Jablonski[50] asserts head hair was evolutionarily advantageous for pre-humans to retain because it protected the scalp as they walked upright in the intense African (equatorial) UV light. While some might argue that, by this logic, humans should also express hairy shoulders because these body parts would putatively be exposed to similar conditions, the protection of the head, the seat of the brain that enabled humanity to become one of the most successful species on the planet (and which also is very vulnerable at birth) was arguably a more urgent issue (axillary hair in the underarms and groin were also retained as signs of sexual maturity). Sometime during the gradual process by which Homo erectus began a transition from furry skin to the naked skin expressed by Homo sapiens, hair texture putatively gradually changed from straight hair (the condition of most mammals, including humanity's closest cousins—chimpanzees) to Afro-textured hair or 'kinky' (i.e. tightly coiled). This argument assumes that curly hair better impedes the passage of UV light into the body relative to straight hair (thus curly or coiled hair would be particularly advantageous for light-skinned hominids living at the equator).

It is substantiated by Iyengar's findings (1998) that UV light can enter into straight human hair roots (and thus into the body through the skin) via the hair shaft. Specifically, the results of that study suggest that this phenomenon resembles the passage of light through fiber optic tubes (which do not function as effectively when kinked or sharply curved or coiled). In this sense, when hominids (i.e. Homo Erectus) were gradually losing their straight body hair and thereby exposing the initially pale skin underneath their fur to the sun, straight hair would have been an adaptive liability. By inverse logic, later, as humans traveled farther from Africa and/or the equator, straight hair may have (initially) evolved to aid the entry of UV light into the body during the transition from dark, UV-protected skin to paler skin.

Some conversely believe that tightly coiled hair that grows into a typical Afro-like formation would have greatly reduced the ability of the head and brain to cool because although African people's hair is much less dense than its European counterpart, in the intense sun the effective 'woolly hat' that such hair produced would have been a disadvantage. However, such anthropologists as Nina Jablonski oppositely argue about this hair texture. Specifically, Jablonski's assertions[50] suggest that the adjective "woolly" in reference to Afro-hair is a misnomer in connoting the high heat insulation derivable from the true wool of sheep. Instead, the relatively sparse density of Afro-hair, combined with its springy coils actually results in an airy, almost sponge-like structure that in turn, Jablonski argues,[50] more likely facilitates an increase in the circulation of cool air onto the scalp. Further, wet Afro-hair does not stick to the neck and scalp unless totally drenched and instead tends to retain its basic springy puffiness because it less easily responds to moisture and sweat than straight hair does. In this sense, the trait may enhance comfort levels in intense equatorial climates more than straight hair (which, on the other hand, tends to naturally fall over the ears and neck to a degree that provides slightly enhanced comfort levels in cold climates relative to tightly coiled hair).

Furthermore, some interpret the ideas of Charles Darwin as suggesting that some traits, such as hair texture, were so arbitrary to human survival that the role natural selection played was trivial. Hence, they argue in favor of his suggestion that sexual selection may be responsible for such traits. However, inclinations towards deeming hair texture "adaptively trivial" may root in certain cultural value judgments more than objective logic. In this sense the possibility that hair texture may have played an adaptively significant role cannot be completely eliminated from consideration. In fact, while the sexual selection hypothesis cannot be ruled out, the asymmetrical distribution of this trait vouches for environmental influence. Specifically, if hair texture were simply the result of adaptively arbitrary human aesthetic preferences, one would expect that the global distribution of the various hair textures would be fairly random. Instead, the distribution of Afro-hair is strongly skewed toward the equator.

Further, it is notable that the most pervasive expression of this hair texture can be found in sub-Saharan Africa; a region of the world that abundant genetic and paleo-anthropological evidence suggests, was the relatively recent (≈200,000-year-old) point of origin for modern humanity. In fact, although genetic findings (Tishkoff, 2009) suggest that sub-Saharan Africans are the most genetically diverse continental group on Earth, Afro-textured hair approaches ubiquity in this region. This points to a strong, long-term selective pressure that, in stark contrast to most other regions of the genomes of sub-Saharan groups, left little room for genetic variation at the determining loci. Such a pattern, again, does not seem to support human sexual aesthetics as being the sole or primary cause of this distribution.

The EDAR locus

A group of studies have recently shown that genetic patterns at the EDAR locus, a region of the modern human genome that contributes to hair texture variation among most individuals of East Asian descent, support the hypothesis that (East Asian) straight hair likely developed in this branch of the modern human lineage subsequent to the original expression of tightly coiled natural afro-hair.[54][55][56] Specifically, the relevant findings indicate that the EDAR mutation coding for the predominant East Asian 'coarse' or thick, straight hair texture arose within the past ≈65,000 years, which is a time frame that covers from the earliest of the 'Out of Africa' migrations up to now.

Disease

Ringworm is a fungal disease that targets hairy skin.[57]

Premature greying of hair is another condition that results in greying before the age of 20 years in Whites, before 25 years in Asians, and before 30 years in Africans.[58]

Hair care

Hair care involves the hygiene and cosmetology of hair including hair on the scalp, facial hair (beard and moustache), pubic hair and other body hair. Hair care routines differ according to an individual's culture and the physical characteristics of one's hair. Hair may be colored, trimmed, shaved, plucked, or otherwise removed with treatments such as waxing, sugaring, and threading.

Removal practices

Depilation is the removal of hair from the surface of the skin. This can be achieved through methods such as shaving. Epilation is the removal of the entire hair strand, including the part of the hair that has not yet left the follicle. A popular way to epilate hair is through waxing.

Shaving

Shaving is accomplished with bladed instruments, such as razors. The blade is brought close to the skin and stroked over the hair in the desired area to cut the terminal hairs and leave the skin feeling smooth. Depending upon the rate of growth, one can begin to feel the hair growing back within hours of shaving. This is especially evident in men who develop a five o'clock shadow after having shaved their faces. This new growth is called stubble. Stubble typically appears to grow back thicker because the shaved hairs are blunted instead of tapered off at the end, although the hair never actually grows back thicker.

Waxing

Waxing involves using a sticky wax and strip of paper or cloth to pull hair from the root. Waxing is the ideal hair removal technique to keep an area hair-free for long periods of time. It can take three to five weeks for waxed hair to begin to resurface again. Hair in areas that have been waxed consistently is known to grow back finer and thinner, especially compared to hair that has been shaved with a razor.

Laser removal

Laser hair removal is a cosmetic method where a small laser beam pulses selective heat on dark target matter in the area that causes hair growth without harming the skin tissue. This process is repeated several times over the course of many months to a couple of years with hair regrowing less frequently until it finally stops; this is used as a more permanent solution to waxing or shaving. Laser removal is practiced in many clinics along with many at-home products.

Cutting and trimming

Because the hair on one's head is normally longer than other types of body hair, it is cut with scissors or clippers. People with longer hair will most often use scissors to cut their hair, whereas shorter hair is maintained using a trimmer. Depending on the desired length and overall health of the hair, periods without cutting or trimming the hair can vary.

Cut hair may be used in wigs. Global imports of hair in 2010 was worth $US 1.24 billion.[59]

Social role

Hair has great social significance for human beings.[60][61] It can grow on most external areas of the human body, except on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet (among other areas). Hair is most noticeable on most people in a small number of areas, which are also the ones that are most commonly trimmed, plucked, or shaved. These include the face, ears, head, eyebrows, legs, and armpits, as well as the pubic region. The highly visible differences between male and female body and facial hair are a notable secondary sex characteristic.

The world's longest documented hair belongs to Xie Qiuping (in China), at 5.627 m (18 ft 5.54 in) when measured on 8 May 2004. She has been growing her hair since 1973, from the age of 13.[62]

Indication of status

Healthy hair indicates health and youth (important in evolutionary biology). Hair color and texture can be a sign of ethnic ancestry. Facial hair is a sign of puberty in men. White hair is a sign of age or genetics, which may be concealed with hair dye (not easily for some), although many prefer to assume it (especially if it is a poliosis characteristic of the person since childhood). Male pattern baldness is a sign of age, which may be concealed with a toupee, hats, or religious and cultural adornments. Although drugs and medical procedures exist for the treatment of baldness, many balding men simply shave their heads. In early modern China, the queue was a male hairstyle worn by the Manchus from central Manchuria and the Han Chinese during the Qing dynasty; hair on the front of the head was shaved off above the temples every ten days, mimicking male-pattern baldness, and the rest of the hair braided into a long pigtail.

Hairstyle may be an indicator of group membership. During the English Civil War, the followers of Oliver Cromwell decided to crop their hair close to their head, as an act of defiance to the curls and ringlets of the king's men.[63] This led to the Parliamentary faction being nicknamed Roundheads. Recent isotopic analysis of hair is helping to shed further light on sociocultural interaction, giving information on food procurement and consumption in the 19th century.[64] Having bobbed hair was popular among the flappers in the 1920s as a sign of rebellion against traditional roles for women. Female art students known as the "cropheads" also adopted the style, notably at the Slade School in London, England. Regional variations in hirsutism cause practices regarding hair on the arms and legs to differ. Some religious groups may follow certain rules regarding hair as part of religious observance. The rules often differ for men and women.

Many subcultures have hairstyles which may indicate an unofficial membership. Many hippies, metalheads, and Indian sadhus have long hair, as well many older indie kids. Many punks wear a hairstyle known as a mohawk or other spiked and dyed hairstyles; skinheads have short-cropped or completely shaved heads. Long stylized bangs were very common for emos, scene kids and younger indie kids in the 2000s and early 2010s, among people of both genders.

Heads were shaved in concentration camps, and head-shaving has been used as punishment, especially for women with long hair. The shaven head is common in military haircuts, while Western monks are known for the tonsure. By contrast, among some Indian holy men, the hair is worn extremely long.

In the time of Confucius (5th century BCE), the Chinese grew out their hair and often tied it, as a symbol of filial piety.

Regular hairdressing in some cultures is considered a sign of wealth or status. The dreadlocks of the Rastafari movement were despised early in the movement's history. In some cultures, having one's hair cut can symbolize a liberation from one's past, usually after a trying time in one's life. Cutting the hair also may be a sign of mourning.

Tightly coiled hair in its natural state may be worn in an Afro. This hairstyle was once worn among African Americans as a symbol of racial pride. Given that the coiled texture is the natural state of some African Americans' hair, or perceived as being more "African", this simple style is now often seen as a sign of self-acceptance and an affirmation that the beauty norms of the (eurocentric) dominant culture are not absolute. It is important to note that African Americans as a whole have a variety of hair textures, as they are not an ethnically homogeneous group, but an ad-hoc of different racial admixtures.

The film Easy Rider (1969) includes the assumption that the two main characters could have their long hairs forcibly shaved with a rusty razor when jailed, symbolizing the intolerance of some conservative groups toward members of the counterculture. At the conclusion of the Oz obscenity trials in the UK in 1971, the defendants had their heads shaved by the police, causing public outcry. During the appeal trial, they appeared in the dock wearing wigs.[65] A case where a 14-year-old student was expelled from school in Brazil in the mid-2000s, allegedly because of his fauxhawk haircut, sparked national debate and legal action resulting in compensation.[66][67]

Religious practices

Women's hair may be hidden using headscarves, a common part of the hijab in Islam and a symbol of modesty required for certain religious rituals in Eastern Orthodoxy. Russian Orthodox Church requires all married women to wear headscarves inside the church; this tradition is often extended to all women, regardless of marital status. Orthodox Judaism also commands the use of scarves and other head coverings for married women for modesty reasons. Certain Hindu sects also wear head scarves for religious reasons. Sikhs have an obligation not to cut hair (a Sikh cutting hair becomes 'apostate' which means fallen from religion)[68] and men keep it tied in a bun on the head, which is then covered appropriately using a turban. Multiple religions, both ancient and contemporary, require or advise one to allow their hair to become dreadlocks, though people also wear them for fashion. For men, Islam, Orthodox Judaism, Orthodox Christianity, Roman Catholicism, and other religious groups have at various times recommended or required the covering of the head and sections of the hair of men, and some have dictates relating to the cutting of men's facial and head hair. Some Christian sects throughout history and up to modern times have also religiously proscribed the cutting of women's hair. For some Sunni madhabs, the donning of a kufi or topi is a form of sunnah.[69]

See also

- Chaetophobia – the fear of hair

- Hair analysis (alternative medicine)

- Hypertrichosis – the state of having an excess of hair on the head or body

- Hypotrichosis – the state of having a less than normal amount of hair on the head or body

- Lanugo

- Seta – hair-like structures in insects

- Trichotillomania – hair pulling

References

Citations

- Sherrow, Victoria (2006). Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. iv. ISBN 978-0-313-33145-9.

- Krause, K; Foitzik, K (2006). "Biology of the Hair Follicle: The Basics". Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 25 (1): 2–10. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2006.01.002. PMID 16616298.

- Feughelman, Max (1997). Mechanical Properties and Structure of Alpha-keratin Fibres: Wool, Human Hair and Related Fibres. UNSW Press. ISBN 978-0-86840-359-5. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Hair Structure and Hair Life Cycle. follicle.com

- "Topic 2". Texascollaborative.org. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Ley, Brian (1999). "Diameter of a Human Hair". Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Councilman, W. T. (1913). "Ch. 1". Disease and Its Causes. United States: New York Henry Holt and Company London Williams and Norgate The University Press, Cambridge, USA.

- Freinkel, R.K.; Woodley, D.T., eds. (15 March 2001). The Biology of the Skin. CRC Press. p. 80. ISBN 9781850700067.

- Histology Guide | Skin Histology.leeds.ac.uk. Retrieved on 18 May 2016.

- "Curly Hair Gene". Bio.davidson.edu. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "Hair type, texture and density | Hairdressing Training". Hairdressing.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- Bubenik, George A. (1 September 2003). "Why do humans get "goosebumps" when they are cold, or under other circumstances?". Scientific American. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- Dean, I.; Siva-Jothy, M. T. (2011). "Human fine body hair enhances ectoparasite detection". Biology Letters. 8 (3): 358–61. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0987. PMC 3367735. PMID 22171023.

- "Neuroscience for Kids – Receptors". Faculty.washington.edu. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "hair biology – functions of the hair fiber and hair follicle". Keratin.com. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Sabah, NH (1974). "Controlled stimulation of hair follicle receptors". Journal of Applied Physiology. 36 (2): 256–7. doi:10.1152/jappl.1974.36.2.256. PMID 4811387.

- Montagna, W. (1985). "The evolution of human skin(?)". Journal of Human Evolution. 14: 3–22. doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(85)80090-7.

- "Images of Nature". Ion.asu.edu. Archived from the original on 8 May 2006. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz; Bojanowski, Maciej (July 2012). "A Supposed Eupelycosaur Body Impression from the Early Permian of the Intra-Sudetic Basin, Poland". Ichnos. 19 (3): 150–155. doi:10.1080/10420940.2012.702549.

- Kardong, K.V. (2002): Vertebrates: Comparative anatomy, function, evolution. 3rd Edition. McGraw-Hill, New York

- Q. Ji; Z-X Luo; C-X Yuan; Tabrum, A. R. (February 2006). "A Swimming Mammaliaform from the Middle Jurassic and Ecomorphological Diversification of Early Mammals". Science. 311 (5764): 1123–7. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1123J. doi:10.1126/science.1123026. PMID 16497926. See also the news item at "Jurassic "Beaver" Found; Rewrites History of Mammals". Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- "Jurassic squirrel's secret is out". The Hindu. 9 August 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- Meng, Qing-Jin; Grossnickle, David M.; Di, Liu; Zhang, Yu-Guang; Neander, April I.; Ji, Qiang; Luo, Zhe-Xi (2017). "New gliding mammaliaforms from the Jurassic". Nature. 548 (7667): 291–296. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..291M. doi:10.1038/nature23476. PMID 28792929.

- Bajdek, Piotr (2015). "Microbiota and food residues including possible evidence of pre-mammalian hair in Upper Permian coprolites from Russia". Lethaia. 49 (4): 455–477. doi:10.1111/let.12156.

- Lingham-Soliar, Theagarten (2014). The vertebrate integument, Vol I. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-3-642-53748-6.

- Rowe, T. B.; Macrini, T. E.; Luo, Z.-X. (19 May 2011). "Fossil Evidence on Origin of the Mammalian Brain". Science. 332 (6032): 955–957. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..955R. doi:10.1126/science.1203117. PMID 21596988.

- Ruben, J.A.; Jones, T.D. (2000). "Selective Factors Associated with the Origin of Fur and Feathers" (PDF). Am. Zool. 40 (4): 585–596. doi:10.1093/icb/40.4.585.

- Plower, R.P. (1897). An introduction to the study of mammals living and extinct. New York: Cornell University Library. p. 11. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

Flat scutes, with the edges in apposition, and not overlaid, clothe both surfaces of the tail of the beaver, rats, and others of the same order, and also of some insectivores and marsupials.

- Teerink, BJ (2003). Hair of West European Mammals: Atlas and Identification Key. Cambridge University Press. p. 224. ISBN 9780521545778.

- Toth, Maria (29 December 2017). Hair and fur atlas of Central European mammals. Pars Ltd. p. 307. ISBN 978-963-88339-7-6. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- Prescott, Tony; Ahissar, Ehud; Izhikevich, Eugene (21 November 2015). Scholarpedia of touch. Paris. ISBN 978-94-6239-133-8. OCLC 932171320.

- Linden, David, J. (March 2015). "Chapter 2". Touch: The Science of Hand, Heart and Mind. Viking. ISBN 978-0241184035.

- Rebora, Alfredo (2010). "Lucy's pelt: when we became hairless and how we managed to survive". International Journal of Dermatology. 49 (1): 17–20. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04266.x. ISSN 1365-4632. PMID 20465604.

- Winter, H.; Langbein, L.; Krawczak, M.; Cooper, D.N.; Jave-Suarez, L.F.; Rogers, M.A.; Praetzel, S.; Heidt, P.J.; Schweizer, J. (2001). "Human type I hair keratin pseudogene phihHaA has functional orthologs in the chimpanzee and gorilla: Evidence for recent inactivation of the human gene after the Pan-Homo divergence". Human Genetics. 108 (1): 37–42. doi:10.1007/s004390000439. PMID 11214905.

- Abbasi, A.A. (2011). "Molecular evolution of HR, a gene that regulates the postnatal cycle of the hair follicle". Scientific Reports. 1: 32. Bibcode:2011NatSR...1E..32A. doi:10.1038/srep00032. PMC 3216519. PMID 22355551.

- "Women and Hair Loss: Possible Causes". WebMD. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Rantala, M.J. (1999). "Human nakedness: Adaptation against ectoparasites?". International Journal for Parasitology. 29 (12): 1987–1989. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(99)00133-2. PMID 10961855.

- Jablonski, N.G.; Chaplin, G. (2010). "Human skin pigmentation as an adaptation to UV radiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (Supplement 2): 8962–8968. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.8962J. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914628107. PMC 3024016. PMID 20445093.

- Bergman, Jerry (2014). "Why mammal body hair is an evolutionary enigma". Creation Research Society Quarterly Journal. 50 (3): 216. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- "Gorillas gave pubic lice to humans, DNA study reveals". National Geographic. 28 October 2010. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Weiss RA (10 February 2009). "Apes, lice and prehistory". J Biol. 8 (2): 20. doi:10.1186/jbiol114. PMC 2687769. PMID 19232074.

- Kittler, R.; Kayser, M.; Stoneking, M. (2004). "Molecular Evolution of Pediculus humanus and the Origin of Clothing" (PDF). Current Biology. 14 (24): 2309. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.024. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- Toups, M.A.; Kitchen, A.; Light, J.E.; Reed, D.L. (2011). "Origin of clothing lice indicates early clothing use by anatomically modern humans in Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (1): 29–32. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq234. PMC 3002236. PMID 20823373.

- Dixson, A.F. (2009). Sexual selection and the origins of human mating systems (1 ed.). Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-955942-8.

- Pagel, Mark; Bodmer, Walter (2003). "A naked ape would have fewer parasites". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 270 (Suppl 1): S117–S119. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0041. PMC 1698033. PMID 12952654.

- Rantala, M.J. (1999). "Human nakedness: Adaptation against ectoparasites?" (PDF). International Journal for Parasitology. 29 (12): 1987–1989. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(99)00133-2. PMID 10961855. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- Giles, James (20 March 2015) [2010]. "Naked love: The evolution of human hairlessness". Biological Theory. 5 (4): 326–336. doi:10.1162/BIOT_a_00062.

- Shea, Christopher (12 July 2011). "Human hairlessness: The naked love explanation". Ideas Market blog. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Couch, Alan (3 February 2016). "Fur or fire: Was the use of fire the initial selection pressure for fur loss in ancestral hominins?". PeerJ Preprints. 4: e1702v1. doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.1702v1. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- Jablonski, Nina G. (1 May 2008). Skin: A Natural History. University of California Press. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-0-520-94170-0. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Bolk, L. (1926). Das Problem der Menschwerdung (in German). Jena: Fischer.

- short-list of 25 characters reprinted in Gould, Stephen Jay (1977). Ontogeny and phylogeny. Harvard University Press. p. 357. ISBN 0674639413.

- Scott, Isabel M. (7 October 2014). "Human preferences for sexually dimorphic faces may be evolutionarily novel". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (40): 14388–14393. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11114388S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1409643111. PMC 4210032. PMID 25246593.

- Fujimoto, A; Kimura, R; Ohashi, J; Omi, K; Yuliwulandari, R; Batubara, L; Mustofa, MS; Samakkarn, U; et al. (2008). "A scan for genetic determinants of human hair morphology: EDAR is associated with Asian hair thickness" (PDF). Human Molecular Genetics. 17 (6): 835–43. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddm355. PMID 18065779.

- Fujimoto, A; Ohashi, J; Nishida, N; Miyagawa, T; Morishita, Y; Tsunoda, T; Kimura, R; Tokunaga, K (2008). "A replication study confirmed the EDAR gene to be a major contributor to population differentiation regarding head hair thickness in Asia" (PDF). Human Genetics. 124 (2): 179–85. doi:10.1007/s00439-008-0537-1. hdl:2241/103672. PMID 18704500. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- Mou, C; Thomason, HA; Willan, PM; Clowes, C; Harris, WE; Drew, CF; Dixon, J; Dixon, MJ; Headon, DJ (2008). "Enhanced ectodysplasin-A receptor (EDAR) signaling alters multiple fiber characteristics to produce the East Asian hair form" (PDF). Human Mutation. 29 (12): 1405–11. doi:10.1002/humu.20795. PMID 18561327. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- "Dermatologyinfo.net". Dermatologyinfo.net. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- "Premature graying of hair". Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- Gupta, Ankush (27 April 2014). "Human Hair "Waste" and Its Utilization: Gaps and Possibilities". Journal of Waste Management. 2014: 1–17. doi:10.1155/2014/498018.

- Ashby, Steven P. (2016). "Archaeologies of Hair: the head and its grooming in ancient and contemporary societies". Internet Archaeology (42). doi:10.11141/ia.42.6.

- Hielscher, Sabine (2016). "Because You're Worth It: Women's daily hair care routines in contemporary Britain". Internet Archaeology (42). doi:10.11141/ia.42.6.13.

- Glenday, Craig (2010). Guinness World Records 2011. ISBN 9781904994572.

- Olmert, Michael (1996). Milton's Teeth and Ovid's Umbrella: Curiouser & Curiouser Adventures in History, p. 53. Simon & Schuster, New York. ISBN 0-684-80164-7

- Brown, Chloe; Alexander, Michelle (2016). "Hair as a Window on Diet and Health in Post-Medieval London: an isotopic analysis". Internet Archaeology (42). doi:10.11141/ia.42.6.12.

- Green, Jonathon, (1999). All Dressed Up: The Sixties and the Counterculture. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-6523-4.

- "G1 – Justiça do CE condena escola por barrar aluno com cabelo 'moicano' – notícias em Ceará" [G1 - CE court condemns school for barring student with 'mohawk' hair - news in Ceara]. G1.globo.com. 28 September 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "G1 – Aluno diz que jogador inspirou 'corte moicano' alvo de ação judicial no CE – notícias em Ceará" [G1 says student inspired 'Mohawk court' subject to legal action in CE - news in Ceara]. G1.globo.com. 30 September 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Dilgeer, Harjinder Singh (2005) Dictionary of Sikh Philosophy, Sikh University Press.

- The War Within Our Hearts – Page 65 Sa'ad Quadri – 2013

Sources

- Iyengar, B. (1998). "The hair follicle is a specialized UV receptor in human skin?". Bio Signals Recep. 7 (3): 188–194. doi:10.1159/000014544. PMID 9672761.

- Jablonski, N.G. (2006). Skin: a natural history. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Rogers, Alan R.; Iltis, David; Wooding, Stephen (2004). "Genetic variation at the MC1R locus and the time since loss of human body hair". Current Anthropology. 45 (1): 105–108. doi:10.1086/381006.

- Tishkoff, S. A.; Dietzsch, E.; Speed, W.; Pakstis, A. J.; Kidd, J. R.; Cheung, K.; Bonne-Tamir, B.; Santachiara-Benerecetti, A. S.; et al. (1996). "Global patterns of linkage disequilibrium at the CD4 locus and modern human origins". Science. 271 (5254): 1380–1387. Bibcode:1996Sci...271.1380T. doi:10.1126/science.271.5254.1380. PMID 8596909.

External links

- How to measure the diameter of your own hair using a laser pointer

- Instant insight outlining the chemistry of hair from the Royal Society of Chemistry

- PUIU, TIBI (23 August 2018). "How fast hair grows, and other hairy science". ZME Science. Retrieved 30 August 2018.