Body louse

The body louse (Pediculus humanus humanus, sometimes called Pediculus humanus corporis) is a hematophagic ectoparasite louse that infests humans. It is one of three such lice, the other two are the head louse, and the pubic louse.

| Body louse | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Phthiraptera |

| Family: | Pediculidae |

| Genus: | Pediculus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. h. humanus |

| Trinomial name | |

| Pediculus humanus humanus | |

Despite the name, body lice do not directly live on the host. They lay their eggs in articles of clothing or bedding and only come into contact with the host whenever they need to feed. Since body lice can't jump or fly, they spread by direct contact with another person or by coming into contact with clothing or bed sheets that are infested.

Body lice are disease vectors because they can transmit the parasites that cause human diseases such as epidemic typhus, trench fever, and relapsing fever. By contrast their close relative the head louse does not transmit diseases. In most developed countries, infestations are only a problem in areas of poverty where there is poor body hygiene, crowded living conditions and the lack of access to clean clothing.[1] Outbreaks can also occur in situations where large groups of people are forced to live in unsanitary conditions. These types of outbreaks are seen globally in prisons, homeless populations, refugees from war, or when natural disasters occur and proper sanitation is not available.

Life cycle and morphology

Pediculus humanus humanus (the body louse) is indistinguishable in appearance from Pediculus humanus capitis (the head louse) but will interbreed only under laboratory conditions. In their natural state, they occupy different habitats and do not usually meet. Compared to the other two related lice species (head and pubic lice), body lice do not directly live on the host. They lay their eggs in articles of clothing or bedding and only come into contact with the host whenever they need to feed.[2] They can feed up to five times a day and can live for about thirty days, but if they are separated from their host, they will die within a week. If the conditions are met, the body louse can reproduce rapidly in favoring conditions.

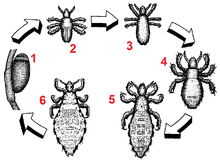

The life cycle of the body louse consists of three stages: egg (also called a nit), nymph, and adult.

- Nits are louse eggs that are laid in the folds of clothing and nowhere else. The mother louse secretes an adhesive that is produced by her accessory gland and hold the egg in place until hatched. They are oval and usually yellow to white in color and when in the correct temperature, they will develop 6 to 9 days after being laid.[3]

- A nymph is an immature louse that hatches from the nit (egg). Once the nymph is hatched, it immediately starts feeding on the hosts blood and then returns to the clothing until it needs to feed again. The nymph will molt three times after hatching and after the third molt, it has developed into an adult louse. The nymph developing into an adult louse usually takes 9-12 days after hatching.[3]

- The adult body louse is about the size of a sesame seed (2.5–3.5 mm), has six legs, wingless and is tan to grayish-white. After the final molt, female and male lice can mate immediately and since the louse typically lives for 20 days before dying, mating is crucial in order to increase their population size.[3] A female louse can lay up to 200-300 eggs in clothing, bed sheet fibers or seams of clothes throughout her life. To live, lice must feed on blood. If separated from their hosts, the lice will eventually die. The digestion of the blood is done by erythrocytes and usually is digested quickly.

The two P. humanus subspecies are anatomically similar and share a lot of the same characteristics. Their heads are short with two antennae that are split into five segments each, compacted thorax, seven segmented abdomen with lateral paratergal plates.[3] Entomologists can distinguish between body and head lice based on differences in pigment coloration in the abdomen segmentation and lengths of tibia's have been observed between the two subspecies.[3]

Origins

The body louse diverged from the head louse at around 100,000 years ago, hinting at the time of the origin of clothing.[4][5][6] Body lice were first described by Carl Linnaeus in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae. The human body louse had its genome sequenced in 2010, and at that time it had the smallest known insect genome.[7] Other lice that infest humans are the head louse and the crab louse. The claws of these three species are adapted to attachment to specific hair diameters.[8]

The body louse belongs to the phylum Arthropoda, class Insecta, order Phthiraptera and family Pediculidae. There has been roughly 5,000 species of lice described, 4,000 specialized to birds, 800 specialized to mammals and are seen all over the world in various habitats.[9]

Signs and symptoms

Body lice infestations can involve thousands of mites, each biting an average of 5 times per day.[10] When an individual is infested with body lice, this condition is called pediculosis. The number and severity of the bites can vary depending on how many lice that individual is infested with. Since an infestation can include thousands of lice and with each of them biting 5 times a day, the bites can cause uncontrollable itching that can result in infections. If an individual or a population of people are exposed to a long-term infestation, they may start to experience apathy, lethargy and fatigue.

When feeding, the body lice resemble a mosquito feeding process. The body louse pierces the skin of the host and injects a salivary anticoagulant that helps the louse consume the hosts blood. Bites of the body louse can produce skin lesions that looks like a rash and in some cases, pruritus. Intense scratching of pruritic bites can result in skin excoriation, potentially leading to significant secondary bacterial infections.[10]

Treatment

Treatment of lice usually involves the manual removal treatment techniques or chemicals known as pediculicides. In many cases, the change in the individuals personal hygiene can treat the body lice without the use of pediculicides. The infected individuals should shower as well as wash all of their clothes, towels, and bed sheets in hot water that is at least 50 °C (122 °F) and dried on the hot cycle. The itching can be treated with topical antibiotics; corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines. If the itching has caused secondary infections, then antibiotics will be prescribed based on the type of infection.

Pediculicides aren't necessarily needed when appropriate hygiene requirements are met, but they can be used in cases where other lice species are present. Since these chemicals that are used can be toxic to humans, the directions need to be followed when applying them. However, many of the most widely used pediculicides have become ineffective as a result of the spread of resistant strains.[11]

Diseases caused

Body lice can cause the cutaneous condition Pediculosis corporis, characterised by intense itching.

Unlike other species of lice they can also act as vectors to transmit disease. Some types of bacterial infections that are transmitted by body lice are Rickettsia prowazekii (causes typhus), Borrelia recurrentis (causes relapsing fever), and Bartonella quintana (causes trench fever). Body lice are dependent on a variety of conditions that can lead to an increase in population. Some conditions that are needed is the weather, humidity and lack of hygiene.[12] Diseases like typhus are reported mainly in the winter/spring months, during these months, individuals have to wear multiple articles of clothing, which serves as a great place for the body louse to live and breed.

All of these diseases negatively impact human health, but can now be treated. If they go without treatment, two of the diseases have a high fatality rate. Typhus can be treated with one dose of doxycycline, but if left untreated, the fatality rate is 30%.[12] Relapsing fever can be treated with tetracycline and depending on the severity of the disease, if left untreated it has a fatality rate between 10–40%.[12] Trench fever can be treated with either doxycycline or gentamicin, if left untreated the fatality rate is less than 1%.[12]

See also

References

- Powers, Jim; Badri, Talel (2020), "Pediculosis Corporis", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29489282, retrieved 2020-02-08

- Powers, Jim; Badri, Talel (2020), "Pediculosis Corporis", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29489282, retrieved 2020-02-08

- Raoult, Didier; Roux, Veronique (1999). "The Body Louse as a Vector of Reemerging Human Diseases". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 29 (4): 888–911. doi:10.1086/520454. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 10589908.

- Ralf Kittler; Manfred Kayser; Mark Stoneking (2003). "Molecular evolution of Pediculus humanus and the origin of clothing" (PDF). Current Biology. 13 (16): 1414–1417. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00507-4. PMID 12932325. Archived from the original on 2007-07-10. Retrieved 2008-09-01.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Stoneking, Mark. "Erratum: Molecular evolution of Pediculus humanus and the origin of clothing". Retrieved March 24, 2008.Archive

- Toups, MA; Kitchen, A; Light, JE; Reed, DL (2010). "Origin of Clothing Lice Indicates Early Clothing Use by Anatomically Modern Humans in Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (1): 29–32. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq234. PMC 3002236. PMID 20823373.

- Kirkness EF, Haas BJ, et al. (2010). "Genome sequences of the human body louse and its primary endosymbiont provide insights into the permanent parasitic lifestyle". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (27): 12168–12173. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10712168K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003379107. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2901460. PMID 20566863.

- Hoffman, Barbara (2012). Williams gynecology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 90. ISBN 9780071716727.

- "Louse", Wikipedia, 2020-04-15, retrieved 2020-04-15

- Powers, Jim; Badri, Talel (2020), "Pediculosis Corporis", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29489282, retrieved 2020-02-08

- de la Filia, A. G.; Andrews, S.; Clark, J. M.; Ross, L. (December 20, 2017). "The unusual reproductive system of head and body lice (Pediculus humanus)". Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 32 (2): 226–234. doi:10.1111/mve.12287. PMC 5947629. PMID 29266297.

- Raoult, Didier; Roux, Veronique (1999). "The Body Louse as a Vector of Reemerging Human Diseases". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 29 (4): 888–911. doi:10.1086/520454. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 10589908.

External links

- Body and head lice on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site