Insular Celts

The Insular Celts are the speakers of the Insular Celtic languages, which comprise all the living Celtic languages as well as their precursors, but the term is mostly used in reference to the peoples of the British Iron Age prior to the Roman conquest, and their contemporaries in Ireland.

According to older theories, the Insular Celtic languages spread throughout the islands in the course of the insular Iron Age. But this is now doubted by most scholars, who see the languages as already present, and possibly dominant, in the Bronze Age. At some point the languages split into the two major groups, Goidelic in Ireland and Brittonic in Great Britain, corresponding to the population groups of the Goidels (Gaels) on one hand and the Britons and the Picts on the other. The extent to which these peoples ever formed a distinct ethnic group remains unclear. While there are early records of the Continental Celtic languages, allowing a comparatively confident reconstruction of Proto-Celtic, Insular Celtic languages become attested in connected texts only at the end of the Dark Ages, from around the 7th century CE, by which time they had become mutually incomprehensible.[1]

Celtic settlement of Britain and Ireland

Archaeology

In older theories, the arrival of Celts, defined as speakers of Celtic languages, which derive from a Proto-Celtic language, roughly coincided with the beginning of the European Iron Age. In 1946 the Celtic scholar T. F. O'Rahilly published his influential model of the early history of Ireland, which postulated four separate waves of Celtic invaders, spanning most of the Iron Age (700 to 100 BCE). However the archaeological evidence for these waves of invaders proved elusive. Later research indicated that the culture may have developed gradually and continuously between the Celts and the indigenous populations. Similarly in Ireland little archaeological evidence was found for large intrusive groups of Celtic immigrants, suggesting to archaeologists such as Colin Renfrew that the native late Bronze Age inhabitants gradually absorbed European Celtic influences and language.

In the 1970s a "continuity model" was popularized by Colin Burgess in his book The Age of Stonehenge which theorised that Celtic culture in Great Britain "emerged" rather than resulted from invasion and that the Celts were not invading aliens, but the descendants of, or culturally influenced by, figures such as the Amesbury Archer, whose burial included clear continental connections.

The archaeological evidence is of substantial cultural continuity through the 1st millennium BCE,[2] although with a significant overlay of selectively adopted elements of the "Celtic" La Tène culture from the 4th century BCE onwards. There are claims of continental-style states appearing in southern England close to the end of the period, possibly reflecting in part immigration by élites from various Gallic states such as those of the Belgae.[3] Evidence of chariot burials in England begins about 300 BC and is mostly confined to the Arras culture associated with the Parisii.

Linguistics

Remnants of pre-Celtic languages may remain in the names of some geographical features, such as the rivers Clyde, Tamar and Thames, whose etymology is unclear but possibly derive from a pre-Celtic substrate (Gelling).

It is thought that by about the 6th century BCE most of the inhabitants of the isles of Ireland and Britain were speaking Celtic languages. A controversial phylogenetic linguistic analysis of 2003 puts the age of Insular Celtic a few centuries earlier, at 2,900 years before present, or slightly earlier than the European Iron Age.[4]

It is not entirely clear if there was ever a "Common Insular Celtic" language, the alternative being that the Celtic settlement of Ireland and Great Britain was undertaken by separate populations speaking separate Celtic dialects from the beginning. However, the "Insular Celtic hypothesis" has been favoured as the most probable scenario in Celtic historical linguistics since the later 20th century (supported by e.g. Cowgill 1975; McCone 1991, 1992; and Schrijver 1995). This would point to a single wave of immigration of early Celts (Hallstatt D) to both Great Britain and Ireland, which however divided into two isolated groups (one in Ireland and one in Great Britain) soon after their arrival, placing the split of Insular Celtic into Goidelic and Brythonic close to 500 BCE. However, this is not the only possible interpretation. In an alternative scenario, the migration could have brought early Celts first to Britain (where a largely undifferentiated Insular Celtic was spoken initially), from whence Ireland was colonised only later. Schrijver has pointed out that according to the absolute chronology of sound changes found in Kenneth Jackson's "Language and History in Early Britain", British and Goidelic were still essentially identical as late as the mid-1st century CE apart from the P/Q isogloss, and that there is no archaeological evidence pointing to Celtic presence in Ireland prior to about 100 BCE.

The Goidelic branch would develop into Primitive Irish, Old Irish and Middle Irish, and only with the historical (medieval) expansion of the Gaels would it split into the modern Gaelic languages (Modern Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx). Common Brythonic, on the other hand, split into two branches, British and Pritenic as a consequence of the Roman invasion of Britain in the 1st century. By the 8th century, Pritenic had developed into Pictish (which would be extinct during the 9th century or so), and British had split into Old Welsh and Old Cornish.

Population genetics

Genetic studies have supported the prevalence of native populations. A study in 2003 by Christian Capelli, David Goldstein and others at University College London showed that genetic markers associated with Gaelic names in Ireland and Scotland are also common in certain parts of Wales and England (in most cases, the Southeast of England with the lowest counts of these markers), and are similar to the genetic markers of the Basque people and most different from Danish and North German people.[5] This similarity supported earlier findings in suggesting a large pre-Celtic genetic ancestry, likely going back to the original settlement of the Upper Paleolithic. The authors suggest, therefore, that Celtic culture and the Celtic language may have been imported to Britain at the beginning of the Iron Age by cultural contact, not "mass invasions". In 2006, two popular books, The Blood of the Isles by Bryan Sykes and The Origins of the British: a Genetic Detective Story by Stephen Oppenheimer discuss genetic evidence for the prehistoric settlement of the British Isles, concluding that while there is evidence for a series of migrations from the Iberian Peninsula during the Mesolithic and, to a lesser extent, the Neolithic eras, there is comparatively little trace of any Iron Age migration.

Later genetic studies regarding Y-DNA Haplogroup I-M284 did find evidence for some Late Iron Age migration of Celtic (La Tène) people to Britain and onto north-east Ireland.[6]

Migration has been shown to play a key role in the spread of the Beaker complex to the British Isles. Genome-wide data from 400 Neolithic, Copper Age and Bronze Age Europeans (including >150 ancient British genomes) have been analysed. The introduction to the British Isles of Beaker complex culture came with incoming high levels of steppe-related ancestry, approximately 90% of the gene pool being replaced within a few hundred years.[7]

Iron Age Britain

The British Iron Age is a conventional name in the archaeology of Great Britain, typically excluding prehistoric Ireland, which had an independent Iron Age culture of its own.[8] The parallel phase of Irish archaeology is termed the Irish Iron Age.[9]

The British Iron Age lasted in theory from the first significant use of iron for tools and weapons in Britain to the Romanisation of the southern half of the island. The Romanised culture is termed Roman Britain and is considered to supplant the British Iron Age.

The only surviving description of the Iron Age populations of the British Isles is that of Pytheas, who travelled to the region in about 325 BCE. The earliest tribal names on record date to the 1st century CE (Ptolemy, Caesar; to some extent coinage), representing the situation at the moment of Roman conquest.

Roman era and Dark Ages

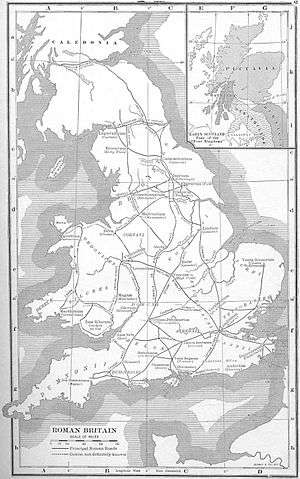

.jpg)

Roman Britain existed for about four centuries, from the mid 1st to the mid 5th century. This led to the formation of a syncretized Romano-British culture in the southern part of Great Britain, comparable in some aspects to Gallo-Roman culture on the continent. However, while in Gaul Roman influence was sufficient to almost wholly replace the Gaulish language with Vulgar Latin, this was nowhere near the case in Roman Britain. Although a British Latin dialect was presumably spoken in the population centres of Roman Britain, it did not become influential enough to displace British dialects spoken throughout the country. There did presumably remain pockets of Romance-speaking populations in Britain as late as the 8th century.[10]

Northern Britain (north of the Antonine Wall) and Ireland would essentially remain in the prehistoric period until after the end of the Roman period. The "protohistoric" period of Ireland can be argued to begin around 400 CE, due to cultural diffusion from Roman Britain, importing writing (ogham, reflecting the earliest records of Primitive Irish) and Christianity. The populations north of Roman Britain are summarized under the term Caledonians (the ancestors of the Picts of later centuries). Very little is known about them other than they posed a constant military threat to the Roman border.

With the Anglo-Saxon invasion and settlement of Great Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries, the British languages were gradually marginalised to the western parts of the island, to what is now Wales and Cornwall. The transition may not necessarily present itself as a mass immigration with a substantial replacement of population, but rather could involve the arrival of a new elite installing their culture and language as a superstrate.[11] A similar process happened as the Gaels installed themselves over the formerly Pictish-speaking populations in Northern Britain. There seems to have been a period of British-Saxon syncretism during the 6th century, with British rulers bearing Saxon names (as in Tewdrig) and Saxon rulers bearing British names (as in Cerdic).[12]

By the end of the Dark Ages, around the 8th century, the Insular Celtic peoples had become the bearers of the Gaelic and Welsh cultures of the historical Gaelic Ireland and Medieval Wales.

See also

- Insular art - embracing much Anglo-Saxon art as well as Celtic art in the post-Roman British Isles

- Celtic toponymy: Insular Celtic

- British toponymy: Celtic

- Goidelic substrate hypothesis

- Insular Celtic languages

- Iron Age Britain

- Genetic history of the British Isles

References

- Bede in the early 8th century is explicit on the Britons, the Irish, and the Pict speaking distinct languages; he also notes that Columba, a Gael, required an interpreter to communicate with the Picts.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2008). A Race Apart: Insularity and Connectivity in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 75, 2009, pp. 55–64. The Prehistoric Society. p. 61.

- Koch, John (2005). Celtic Culture : A Historical Encyclopedia. ABL-CIO. pp. 197–198. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- Russell D. Gray & Quentin D. Atkinson, "Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin", Nature, 2003.

- Capelli, Cristian; et al. (May 27, 2003). "A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles" (PDF). Current Biology. 13: 979–984. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00373-7. PMID 12781138.

- McEvoy and Bradley, Brian P and Daniel G (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 5: Irish Genetics and Celts. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- Reich, David (21 Feb 2018). "The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe". Nature. 555: 190-196.

- Cunliffe (2005) p. 27.

- Raftery, Barry (2005). "Iron-age Ireland". In O Croinin, Daibhi (ed.). Prehistoric and Early Ireland: Volume I. Oxford University Press. pp. 134–181. ISBN 0-19-821737-4. ISBN 978-0-19-821737-4.

- Loyn, Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, 2nd ed. 1991 11

- Pattison, John E. (2008), "Is it Necessary to Assume an Apartheid-like Social Structure in Early Anglo-Saxon England?", Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275 (1650) 2423–2429; doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0352

- "Records of the West Saxon dynasties survive in versions which have been subject to later manipulation, which may make it all the more significant that some of the founding 'Saxon' fathers have British names: Cerdic, Ceawlin, Cenwalh." in: Hills, C., Origins of the English, Duckworth (2003), p. 105. Also "The names Cerdic, Ceawlin and Caedwalla, all in the genealogy of the West Saxon kings, are apparently British." in: Ward-Perkins, B., Why did the Anglo-Saxons not become more British? The English Historical Review 115.462 (June 2000) p. 513. P. Sims-Williams, Religion and Literature [in Western England, 600–800], Cambridge 1990, p. 26.