Norwegian Police Service

The Norwegian Police Service (Norwegian: Politi- og lensmannsetaten) is the Norwegian civilian police agency. It consists of a central National Police Directorate, seven specialty agencies and twelve police districts. The government agency is subordinate to the Ministry of Justice and Public Security and has 16,000 employees, of which 8,000 are police officers. In addition to police powers, the service is responsible for border control, certain civil duties, coordinating search and rescue operations, counter-terrorism, highway patrolling, writ of execution, criminal investigation and prosecution.

| Norwegian Police Service Politi- og lensmannsetaten | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

| Common name | Politi |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 13th century |

| Employees | 13,000 |

| Annual budget | 13 billion kr (2010) |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| National agency | Norway |

| Operations jurisdiction | Norway |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Minister responsible | |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent agency | Ministry of Justice and Public Security |

| National units | List

|

| Police districts | 12 |

| Facilities | |

| Stations | 66 |

| Sheriff's offices | 301 |

| Helicopters | 2 Eurocopter EC135 |

| Website | |

| politi.no | |

The police service dates to the 13th century when the first sheriffs were appointed. As the first city in Norway to do so, Trondheim had a chief of police appointed in 1686, and Oslo established a uniformed police corps in 1859. The directorate is led by National Police Commissioner Odd Reidar Humlegård. Police districts were introduced in 1894, with the current structure dating from 2003.

Each police district is led by a chief of police and is subdivided into several police stations in towns and cities, and sheriffs' offices for rural areas. The Governor of Svalbard acts as chief of police for Svalbard. Norwegian police officers do not carry firearms, but keep their Heckler & Koch MP5 submachine guns and Heckler & Koch P30 pistols locked down in the patrol cars. The Norwegian Prosecuting Authority is partially integrated with the police.

Specialist agencies within the services include the National Criminal Investigation Service, the National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime (Økokrim), the National Police Immigration Service, the National Mobile Police Service, the Norwegian Border Commissioner, the National Police Computing and Material Service and the Norwegian Police University College. Several other national responsibilities are under the command of Oslo Police District, such as the Emergency Response Unit and the two police helicopters. The Police Security Service is separate from the National Police Directorate.

History

The police force in Norway was established during the 13th century. Originally the 60 to 80 sheriffs (lensmann) were predominantly used for writ of execution and to a less degree police power. In the cities the duties were originally taken care of by a gjaldker. The sheriffs were originally subordinate to the sysselmann, but from the 14th century they instead became subordinate to the bailiff (fogd) and the number of sheriffs increased. In the cities the police authority was transferred directly to the bailiff. By the mid-17th century there were between 300 and 350 sheriffs. With the introduction of the absolute monarchy in 1660 and subsequent strengthening of the civil service, the importance of the police increased. The bailiffs as such became part of the police structure, with their superiors, the county governor, receiving a similar role as that of chief of police. The first titled chief of police was hired in Trondheim in 1686, thus creating the first police district, although his jurisdiction only covered the city proper. Chiefs of police were hired in Bergen in 1692, Christiania (Oslo) in 1744 and Christianssand in 1776.[1]

From the 19th century, deputies were hired in larger areas to assist the sheriffs. Following the democratization in 1814, the Ministry of Justice was created in 1818 and has since had the primary responsibility for organizing the police force. The 19th century saw a large increase in the number of chiefs of police, reaching sixteen by the middle of the century. Christiania established the country's first uniformed corps of constables in 1859, which gave the force a more unified appearance. Similar structures were soon introduced in many other cities. From 1859 the municipalities would finance the wages of the deputies and constables, which made it difficult for the police to use those forces outside the municipal borders.[1] The first organized education of police officers started in Christiania in 1889.[2]

In 1894 the authorities decided to abolish the position of bailiff and it was decided that some of its tasks would be transferred to the sheriffs. This resulted in 26 new chief of police positions, largely corresponding to the old bailiwicks. Some received jurisdiction over both cities and rural areas, other just rural areas. At the same time the existing police districts were expanded to include the surrounding rural areas. However, the individual bailiff were not removed from office until their natural retirement, leaving some bailiwick in place until 1919. The reform eliminated the difference between the rural and city police forces; yet the sheriffs were only subordinate to the chief of police in police matters—in civil matters and administration they remained under the county governors.[1]

The police school was established in 1920[2] and the Governor of Svalbard was created in 1925.[3] To increase the police force's flexibility, the municipal funding was cut and replaced with state funding in 1937.[1] That year also saw the first two specialty agencies were created, the Police Surveillance Agency (later the Police Security Service) and the Mobile Police Service.[4] After a border agreement was reached between Norway and the Soviet Union in 1949, the Norwegian Border Commission was established the following year.[5] The Criminal Investigation Service was established in 1959,[4] and the search and rescue system with two joint coordination centers and sub-centers for each police district was created in 1970.[6]

The number of police districts was nearly constant from 1894 to 2002, although a few have been creased and closed.[1] However, the organization in the various police districts varied considerably, especially in the cities. In particular, some cities had their civilian responsibilities taken care of by the municipality. This was confusing for the public, resulting in the police services reorganizing to a homogenous organization during the 1980s, whereby the civil tasks being organized as part of the police stations.[4] Økokrim was established in 1988[7] and in 1994 the administrative responsibilities for the sheriff's offices was transferred to police districts.[1] Only once has the order to shoot to kill been issued, during the Torp hostage crisis in 1994.[8] The police school became a university college in 1993 and introduced a three-year education; in 1998 a second campus opened in Bodø.[2] Police Reform 2000 was a major restructuring of the police force. First the National Police Directorate was created in 2001,[9] and from 2003 the number of police districts were reduced from 54 to 27.[1] The Police Computing and Material Service and the Criminal Investigation Service were both established in 2004.[7] Ten police officers have been killed in service since 1945.[10] The Gjørv Report following the 2011 Norway attacks criticized several aspects of the police force, labeling the work as "unacceptable".[11] National Commissioner Øystein Mæland withdrew following the criticism, in part because an internal report of the attacks had not found any criticism of the police force.[12]

Structure

The National Police Directorate, located in Downtown Oslo, is the central administration for the Norwegian Police Service. It conducts management and supervision of the specialist agencies and police districts, including organizational development and support activities.[9] The directorate is led by the National Police Commissioner, who, since 2012, has been Odd Reidar Humlegård.[13] The National Criminal Investigation Service is a national unit which works with organized and serious crime. It both works as an assistant unit for police districts, with special focus on technical and tactical investigation, in addition to being responsible on its own for organized crime. It acts as the center for international police cooperation, including participation in Interpol and Europol.[14] The National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime is responsible for complex cases of economic crime and acts as a public prosecutor for those cases.[15] The National Police Immigration Service registers and identifies asylum seekers and returns those which have their applications rejected.[16] The National Mobile Police Service is based in Stavern and operates throughout the country. Their primary role is as highway patrol and manages the police reserves, although they also assist police districts in extraordinary events where extra manpower is needed or where they are in the vicinity.[17]

The Norwegian Border Commissioner is located in Kirkenes and is responsible for managing the Norway–Russia border and upholding the border agreement. Special consideration is needed as it is the only non-Schengen Area land border of Norway. Border controls are the responsibility of the respective police district. The National Police Computing and Material Service is responsible for managing the police's information and communications technology, procurement, security and real estate.[18] Norway has two joint rescue coordination centers, one for Northern Norway located in Bodø and on one for Southern Norway located in Sola. Their jurisdiction border goes at the 65th parallel north (Nord-Trøndelag–Nordland border). Organizationally they are directly subordinate to the Ministry of Justice and the Police, although their operations are subordinate to the chiefs of police in Salten and Rogaland, respectively.[19] The Police Security Service is Norway's security agency; although considered a law enforcement agency, it is not subordinate to the National Police Directorate nor part of the Norwegian Police Service.[20]

Metropolitan Norway is divided into 27 police districts. Each district is further subdivided into local police stations and rural police districts, the latter led by a sheriff. Each police district is headquartered at a main police station and is led by a chief of police. Police districts hold a common pool of resources and personnel and have a common administration and budget. Each also has a joint operations center which also acts as an emergency call center for 112. Many of the larger districts have their own execution and enforcement authority, while this in integrated in the smaller districts.[21] The size of the police districts varies, from Oslo with 2,500 employees and covering a population of 570,000[22] to Eastern Finnmark which has 160 employees and 30,000 residents.[23]

Each districts has specially-trained mobile units for armed and other challenging missions, and dog units for narcotics and search and rescue missions. The police districts also have police boats for coastal waters and selected lakes, with focus on driving under the influence, speeding and environmental monitoring.[24] In Troms and Finnmark, the Reindeer Police are responsible for monitoring and supervising reindeer husbandry and environmental supervision.[25] As of 2009 there were 301 rural police districts, 68 local police stations and 10 execution and enforcement authorities.[26]

Oslo Police District has a series of special divisions and task forces which provide aid to all other police districts when necessary. It is responsible for the two police helicopters, which is mostly used for traffic motoring, search and rescue and apprehension.[25] The Emergency Response Unit is a deployment unit for terrorism, sabotage and hostage incidents, which is separate from the crisis and hostage negotiation service. Oslo's dog patrol service includes the national bomb squad. The departments further has a mobile deployment squad against demonstrations and riots, a Police Negotiation Unit for use against barricades and kidnapping, a mounted police, and the responsibility for protecting high-ranking government and royal officials.[27]

Svalbard is not part of the regular police districts—instead it law enforcement it handled by the Governor of Svalbard. He holds the responsibility as both county governor and chief of police, as well as holding other authority granted from the executive branch. Duties include environmental policy, family law, law enforcement, search and rescue, tourism management, information services, contact with foreign settlements, and abjudication in some areas of maritime inquiries and judicial examinations—albeit never in the same cases as acting as police.[28] Jan Mayen is subordinate to Salten Police District.[29]

Jurisdiction and capabilities

Norway has a unified police, which means that there is a single police organization and that police power and prosecutor power is not granted to other agencies within Norway.[30] The sole exception is the military police, albeit which only has jurisdiction over military personnel and on military installations, except during martial law.[31] The police are decentralized and generalized to allow a more flexible resource allocation, while remaining under political control. This entails that police officers have no geographical or sector limitations to their powers.[30] The Police Act and several special laws regulate the agencies and the officer's powers and responsibilities.[7] The police are required to assist other public institutions, including the healthcare authorities, and can be asked by other agencies to assist when it is necessary to enact a decision by force. Conversely, the police can ask for assistance from the Coast Guard when necessary. The police are responsible for all responses against terrorism and sabotage unless Norway is under armed attack.[7]

Responsibilities and functions related to security includes patrolling, continual emergency availability, highway patrolling, sea patrolling, coordination of search and rescue activities, embassy security and as a body guard service for members of the government, the royal family and other in need. The crime fighting responsibility is split between preventative measures, such as information, observation and controls, and consequential measures, such as investigation and prosecution. The police further have duties related to civilian court cases, such as writ of execution, evaluation of natural damage, assisting the courts after bankruptcies and functioning as a notary public.[7]

The police have a series of functions related to public management, such as the issuing of passports, firearms licenses, police certificates, permissions for lotteries and withdrawal of driving licenses, approval of security guard companies and bouncers, recommendations to municipal councils for issuing alcohol sales licenses, approval of second-hand shops and arrangements which are otherwise unlawful, dealing with unowned dogs and animals in the care of people sentenced unsuitable to hold animals.[7]

The police also have the responsibility for prisoner transport during detention, including transport to and from court. The police serve as border guards for the outer border of the Schengen Area. The busiest are Oslo Airport, Gardermoen, which has 130 man-years tied to it, Storskog on the Russian border and Sandefjord Airport, Torp. These are the only borders with designated border employees—all other are manned with regular officers. The police is not responsible for customs, which is the responsibility of the Norwegian Customs and Excise Authorities. Norway participates in a series of international police cooperation, such as Interpol, Europol, the Schengen Information System, Frontex, and the Baltic Sea Task Force on Organized Crime. Norway also has a close cooperation with the other Nordic police forces. The Norwegian Police Service occasionally participates in international operations.[7]

In 2011 the police force had 746,464 assignments, the most common with 180,000 assignments being investigation cases, such as reported deaths, controls and reports of motor vehicle theft. This was followed by traffic assignments, public disturbance of peace, animal cases, theft, private disturbance of peace, and sickness and psychiatry. Seventy-five percent of assignments are solved with a single patrol, while ninety percent are solved with one and two. In armed situations only twenty percent are solved with a single patrol.[32] In 2010 the Norwegian Police Service had 13 billion Norwegian krone in costs, of which seventy percent was used on wages. It employed 13,493 man-years, or 1.6 man-years per 1000 residents. There were 394,137 reported offenses, or 81.1 per 1000 people, of which 46 percent were solved. There were 5,399 debt settlements, 226,491 applications for writ of execution, 195,345 immigration cases and 4,615 forced returns.[33]

Investigation and prosecution

The Norwegian Prosecuting Authority is integrated into the Norwegian Police Service. The authority is divided into a higher and lower authority, with the higher authority (public prosecutor) being a separate government agency and the lower authority (police prosecutor) being members of the police. The latter includes chief of police, deputy chief of police, police prosecutors and deputy police prosecutors. In questions of prosecution the police districts are subordinate to the Norwegian Prosecuting Authority and in other matters subordinate to the National Police Directorate.[7]

The higher authorities will take decisions in serious criminal charges and for appeals.[34] The Norwegian Persecuting Authority is led by the Director General of Public Prosecutions,[35] which since 1997 has been Tor-Aksel Busch.[36] The director general makes decisions of indictment in cases with a maximum penalty of twenty-one years and certain other serious crimes.[35] There are twelve subordinate agencies, ten regional and two supporting Kripos and Økokrim, respectively. The regional public prosecution offices take decisions regarding cases not covered by the director general or the police prosecutors.[37]

If an offense is filed, the issue may be investigated by police on duty. Permission for search and seizure is issued by the police prosecutor on duty at the police district. Apprehended people are permitted a free defense counsel at the public's expense. If the police wish to keep apprehended people in detention, the issue is brought to the relevant district court, a process which may be repeated several times if the custody needs to be extended. Investigations are led by a police prosecutor. During investigation, the case may be concluded as a non-criminal offense, dismissed, or transferred to another police district. Minor cases with a positive finding may be resolved by police penalty notice, settlement by a conflict resolution board and withdrawal of prosecution.[38]

Criminal cases with an assumed perpetrator are sent to the public prosecutor, who will consider issuing an indictment. If positive, the trial will take place at a district court, with a police prosecutor presiding over the case.[38] Cases with more than six years maximum penalty will normally be carried out with public prosecutors prosecuting.[35] Either party can, on specified terms, appeal the outcome of the case to the court of appeal and ultimately the Supreme Court of Norway.[38]

Education and employment

Education of police officers is the responsibility of the Norwegian Police University College, which is subordinate to the National Police Directorate. The main campus is located at Majorstuen in Oslo, while the secondary campus is located at Mørkved in Bodø. In addition the college has training centers in Kongsvinger and Stavern.[39] Police officer training is a three-year bachelor's degree, where the first and third year take place at the college and the second year is on-the-ground training in police districts.[40]

In 2009, 1990 people applied for 432 places at the college. From 2010, admission is administrated through the Norwegian Universities and Colleges Admission Service.[41] The college also has a three-year part-time master's degree in police science.[42] As the chief of police and deputy chief of police are part of the prosecuting authority, they must be a candidate of law to act in such a position.[7] Although there no longer is a formal requirement for such an education, the role as prosecutor effectively hinders others from holding the position.[43]

At the time of graduation all officers are qualified for operational service. However, each employee must undergo 40 hours of yearly training, including firearms practice, to keep their operational certification. Without this, they cannot patrol, use firearms or participate in actions. Forty-four percent of police officers in 2012 lacked such certification. The main reason is that the police districts see it as a waste of resources to train investigation and administrative staff which do not participate in operative duty, and that a higher quality is achieved through specialization of tasks, such as dedicated investigation personnel.[32]

Each police district may dictate that operational personnel have a higher amount of training, for instance 80 hours is required in Oslo. Officers are certified at five levels, of which the top four can use firearms. Level three consists of a call-out unit for each police district, consisting of a combined 646 people. This requires 103 hours of special training per year. Higher levels are required for body-guard service (55 officers) and the Emergency Response Union (73 officers). All certification curriculum is developed by and organized by the university college.[32]

The Norwegian Police Federation is the trade union which organizes employees from all levels within the police force.[44] The federation is a member of the Confederation of Unions for Professionals, Norway[45] and the European Confederation of Police.[46] It is illegal for police officers to strike.[47] The federation have nonetheless undertaken several actions, including collective sick leave to close a police station and by members sabotaging courses by not participating.[48] Reports of misconduct and criminal offenses by officers during duty is investigated by the Norwegian Bureau for the Investigation of Police Affairs. Based in Hamar, it is directly subordinate to the Ministry of Justice and the Police and is not part of the Norwegian Police Service.[49]

Equipment

As of 2011 the police's new patrol cars are four-wheel drive Volkswagen Passat with automatic transmission. New transport cars are Mercedes-Benz Vito for light transport and Mercedes-Benz Sprinter for heavy transport.[50] The police force operates two Eurocopter EC135 and two AW169 helicopters, which are based at Oslo Airport, Gardermoen.[51] In addition, the Emergency Response Unit can use the Royal Norwegian Air Force's Bell 412 helicopters.[52]

The police have two main types of uniforms, type I is used for personnel which primarily undertake indoor work, and type II is used for personnel which primarily undertakes outdoor service. Both types have summer and winter versions, and type I also has a dress uniform version.[53] Both types use black as the dominant color with light blue shirts.[54][55]

Police officers are not armed with firearms during patrolling, but have weapons locked down in the patrol cars. Arming of the locked-down weapons requires permission from the chief of police or someone designated by him.[56] The police use Heckler & Koch MP5 submachine guns and Heckler & Koch P30 semi-automatic pistols.[57] The Emergency Response Unit uses Diemaco C8 assault rifles.[58] Norwegian police officers do not use electroshock weapons.[59]

Previously the police used a decentralized information technology system developed during the mid-1990s.[60] As late as 2012 servers were still being run with Windows NT 4.0 from 1996 and log-on times were typically twenty minutes. The new IT-system D#2 was introduced in 2011 and will have been taken into use by all divisions by 2012.[61] D#2 will be operated by ErgoGroup and will have two redundant server centers. Personnel have access to the system via thin clients.[62] The police have a system to raise a national alarm to close border crossings and call in reserve personnel. The one time it was activated the message was not received by any of the intended recipients.[63] Since 2009 it has been possible to report criminal damage and theft of wallets, bicycles and mobile telephones without a known perpetrator(s) online.[64]

The Norwegian Public Safety Radio has been installed in Oslo, Østfold, Akershus and southern Buskerud.[65] The system is uses Terrestrial Trunked Radio and allows for a common public safety network for all emergency agencies. Features include authentication, encryption and possibilities to transmit data traffic.[66] As the system is rolled out, central parts will receive transmission speeds of 163 kbit/s.[67] The rest of the country uses an analog radio system specific for each police district. In addition to lack of interoperability with paramedics and fire fighters, none of the systems are encrypted, forcing police officers to rely heavily on GSM-based mobile telephones for dispatch communication when transmitting sensitive information.[68]

Police cars lack GPS navigation devices and mobile data terminal. Instead, all communication must be radioed to the dispatcher at the joint operations center, and officers must rely on printed road atlases for navigation. In contrast, GPS navigation and terminal equipment was finished installed in ambulances and fire trucks in 2003.[69] The Norwegian Public Safety Radio is scheduled for completion in 2015.[70]

It was reported in November of 2018 that the Norweigian Police had adopted the SIG Sauer P320 X-series 9mm handgun as their new service pistol. [71] [72]

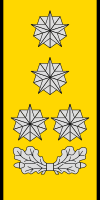

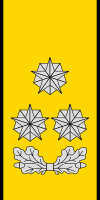

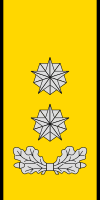

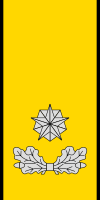

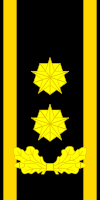

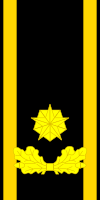

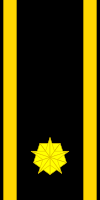

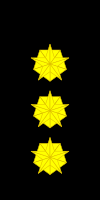

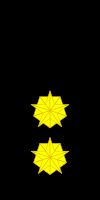

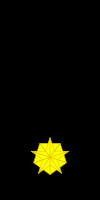

Ranks[73]

| Rank | Politidirektør | Assisterende politidirektør | Politimester | Visepolitimester | Politiinspektør Politiadvokat (appointed before 1 Aug 2002) |

Politiadvokat (appointed after 1 Aug 2002) | Politifullmektig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translation | Police Director | Assistant Police Director | Police Master | Vice Police Master | Police Inspector Police Advocate |

Police Advocate | Police Proxy |

| Official Translation | National Police Commissioner | Assistant National Commissioner | Chief of Police | Deputy Chief of Police | Assistant Chief of Police Police Prosecutor |

Police Prosecutor | Junior Police Prosecutor |

| Equivalent[74] | Chief Constable | Assistant Chief Constable | Superintendent | ||||

| Insignia |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

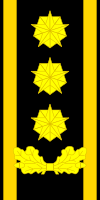

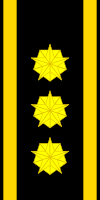

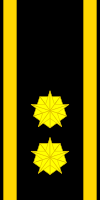

| Rank | Politistasjonssjef Lensmann Politioverbetjent (appointed before 1 Aug 2002) |

Politioverbetjent (appointed after 1 Aug 2002) | Politiførstebetjent | Politibetjent 3 | Politibetjent 2 | Politibetjent 1 | Politireserven |

| Former Rank | Politiassisterendestasjonssjef | Politisjefinspectør | Politiførsteinspectør | Politioverbetjent (Overkonstabel) | Politibetjent (Konstabel) | ||

| Translation | Police Station Chief Sheriff Police Senior Constable |

Police Senior Constable | Police First Constable | Police Constable 3 | Police Constable 2 | Police Constable 1 | Police Reserve |

| Official Translation | Police Chief Superintendent | Police Superintendent | Police Chief Inspector | Police Inspector | Police Sergeant | Police Constable | Police Reserve |

| Equivalent | Chief Inspector | Inspector | Inspector | Sergeant | Sergeant | Constable | Special Constable |

| Insignia |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

See also

References

- "3.8 Historikk". Politireform 2000 Et tryggere samfunn (in Norwegian). Ministry of Justice and the Police. 12 January 2001. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Historie" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Police University College. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- Arlov, Thor B. (1994). A short history of Svalbard. Oslo: Norwegian Polar Institute. p. 68. ISBN 82-90307-55-1.

- "3.9 Organisasjonsutvikling fra 70 årene til i dag". Politireform 2000 Et tryggere samfunn (in Norwegian). Ministry of Justice and the Police. 12 January 2001. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- Johanson, Bodil B. "Overenkomsten" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Norwegian Border Commissioner. p. 41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- "The Norwegian Search and Rescue Service" (PDF). Ministry of Justice and the Police. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "4 Politiets organisering, oppgaver og oppgaveløsning". Politiets rolle og oppgaver (in Norwegian). Ministry of Justice and the Police. 24 June 2005. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "– Jeg var både dommer og bøddel". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). 12 March 2003. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- National Police Directorate (2010): 7

- Gjerstad, Tore (4 March 2010). "Ti politimenn drept siden krigen". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Norway police 'could have stopped Breivik sooner'". BBC News. 13 August 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- "Norway police chief quits over Breivik report". BBC News. 16 August 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- Hamnes, Leif (17 August 2012). "Politimestrene uenige om Humlegård er rett mann til å bli ny politidirektør". Teknisk Ukeblad (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- National Police Directorate (2010): 15

- National Police Directorate (2010): 16

- National Police Directorate (2010): 17

- National Police Directorate (2010): 17–18

- National Police Directorate (2010): 18

- "Welcome". Joint Rescue Coordination Centres Southern Norway and Northern Norway. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- National Police Directorate (2010): 5

- National Police Directorate (2010): 8

- "Om Oslo politidistrikt" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Police Service. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- "Om Østfinnmark politidistrikt" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Police Service. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- National Police Directorate (2010): 11

- National Police Directorate (2010): 12

- "Desentraliserte enheter og antall" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Social Science Data Services. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- National Police Directorate (2010): 13

- "The administration of Svalbard". Report No. 9 to the Storting (1999-2000): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 29 October 1999. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "FOR 1962-06-01 nr 3341: Instruks for sjefen for den militære stasjon på Jan Mayen for så vidt angår fremmedkontroll og fiskerioppsyn" (in Norwegian). Lovdata. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "2 Grunnprinsipper for norsk politi". Politiets rolle og oppgaver (in Norwegian). Ministry of Justice and the Police. 24 June 2005. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Lov om politimyndighet i det militære forsvar" (in Norwegian). Lovdata. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Foss, Andreas Bakke (31 August 2012). "En av to politifolk får ikke lov til å rykke ut". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- "Politiet som del av påtalemyndigheten" (in Norwegian). Statistics Norway. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Police and prosecution – StatRes" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Police Service. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- National Police Directorate (2010): 29

- Foss, Andreas Bakke (22 June 2012). "– Hun bør bli vår neste riksadvokat". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- "Welcome to The higher prosecution autorothies – The Director of Public Prosecutions and the Regional Public Prosecution Offices". Norwegian Prosecuting Authority. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- National Police Directorate (2010): 31–33

- "Om PHS" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Police University College. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Norway". Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Opptakstatistikk" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Police University College. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Master" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Police University College. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "3.6 Kompetanse". Politireform 2000 Et tryggere samfunn (in Norwegian). Ministry of Justice and the Police. 12 January 2001. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Politiets Fellesforbund" (in Norwegian). Confederation of Unions for Professionals, Norway. 11 October 2011. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "English". Confederation of Unions for Professionals, Norway. 11 October 2011. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Full list". European Confederation of Police. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "3 Streikeforbudet for politiet". Streikerett for politiet og lensmannsetaten. Norges Offentlige Utredninger (in Norwegian). Ministry of Justice and the Police. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Tuastad, Svein (17 August 2012). "Ukulturen i politiet". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Om PHS" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Bureau for the Investigation of Police Affairs. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Byberg, Øystein (20 September 2011). "Politiet valgte VW Passat" (in Norwegian). Hegnar Online. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Helsingeng, Terje (8 March 2012). "Nytt politihelikopter på plass 1. juni". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012."Politidirektøren fikk en luftetur i sitt nye 100 millioner kroners-helikopter". TU.no (in Norwegian). Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- "12 Helikopter og beredskap". Rapport fra 22. juli-kommisjonen. Norges Offentlige Utredninger (in Norwegian). Office of the Prime Minister. 13 August 2012. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Kapittel 2 – Tjenesteantrekk" (in Norwegian). National Police Computing and Material Service. Archived from the original on 3 November 2005. Retrieved 3 November 2005.

- "Tjenesteantrekk II – Grunnform" (in Norwegian). National Police Computing and Material Service. Archived from the original on 3 November 2005. Retrieved 3 November 2005.

- "Tjenesteantrekk I – Grunnform" (in Norwegian). National Police Computing and Material Service. Archived from the original on 3 November 2005. Retrieved 3 November 2005.

- "6.7.2 Politiets bevæpningsadgang". Politiets rolle og oppgaver (in Norwegian). Ministry of Justice and the Police. 24 June 2005. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Bråten, Knut (21 September 2008). "Legger vekk revolveren". Drammens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Klungveit, Harald S. (22 November 2007). "Skytemistenkt var i statsministerens livvaktstyrke". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Wernersen, Camilla (18 February 2012). "Over 500 døde av politiets elektrosjokkpistol" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Oreld, Michael (23 September 2008). "Mer it-trøbbel for politiet". Computerworld (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Mortvedt, Ole (23 January 2012). "– Som en bil uten girkasse". Politiforum (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Kirknes, Leif Martin (29 March 2011). "Politiet får to nye datasentre". Computerworld (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Zachariassen, Espen (13 August 2012). "Riksalarm stoppet av intern krangel". Teknisk Ukeblad (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- Hovland, Kjetil Malkenes (31 August 2009). "Anmeld på nett". Teknisk Ukeblad (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- "Nødnett åpnes offisielt" (in Norwegian). Directorate for Civil Protection and Emergency Planning. 16 August 2010. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- Hamnes, Leif (11 March 2010). "Tidsnød-nettet". Teknisk Ukeblad (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- "Produkter og løsninger" (in Norwegian). Nokia Siemens Networks. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- Ministry of Justice and the Police (4 November 2004). "Framtidig radiosamband for nød- og beredskapsetatene" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Government.no. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- Rugland, Ingvild; Torvund, Øyvind (16 September 2012). "Ambulansene fikk GPS i 2003. Politiet i Bergen kjører fortsatt rundt med kartbok". Dagens Næringsliv (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "13 Nødnett". Rapport fra 22. juli-kommisjonen. Norges Offentlige Utredninger (in Norwegian). Office of the Prime Minister. 13 August 2012. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- https://www.all4shooters.com/en/shooting/pistols/sig-sauer-p320-x-series-for-the-norwegian-police/

- https://www.americanrifleman.org/articles/2018/11/9/sig-sauer-p320-x-series-new-sidearm-for-norwegian-police/

- Norwegian National Police

- Approximate British equivalent by level of responsibility.

- Bibliography

- National Police Directorate (2010). "The Police in Norway" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.