Egyptian–Ottoman War (1831–1833)

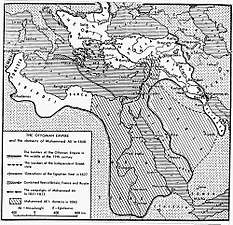

The First Egyptian–Ottoman War, First Turco-Egyptian War or First Syrian War (1831–1833) was a military conflict between the Ottoman Empire and Egypt brought about by Muhammad Ali Pasha's demand to the Sublime Porte for control of Greater Syria, as reward for aiding the Sultan during the Greek War of Independence. As a result, Muhammad Ali's forces temporarily gained control of Syria, advancing as far north as Kütahya.[1]

| Egyptian–Ottoman War (1831–1833) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

|

| ||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

|

|

| ||||

Background

Muhammad Ali Pasha is recorded as planning to extend his rule to the Ottoman Empire's Syrian provinces as early as 1812, secretly telling the British consul of his designs on the territory that year.[1] This desire was left on hold, however, as he consolidated his rule over Egypt, modernizing its government administration, public services, and armed forces, and suppressing various rebellions, including Mameluk and Wahhabi uprisings—on behalf of Sultan Mahmud II.[1]

In 1825, the Sultan again called on Muhammad Ali to suppress a local uprising, this time a nationalist revolution by Greek Christians. He was promised rule over Crete, Cyprus, and the Morea (the modern Peloponnese) for his services.[1] His son, Ibrahim Pasha, won quick victories at the head of a conscript army and controlled nearly the entire Peloponnesian peninsula within 10 months of his arrival in February 1825.[2] The Greeks continued guerrilla operations however, and by September 1827 public opinion in Russia, Britain, and France forced the great powers to intervene in favour of the Greeks.[2] The joint British–Russian–French fleet destroyed Mehmed Ali's fleet that October at the Battle of Navarino, and Ibrahim’s forces were expelled from the Morea a year later following the arrival of a French expeditionary force and a settlement negotiated by the European powers.[3] Once Ibrahim and his forces returned from Greece, preparations to wrest control of Syria began in earnest.[3]

Invasion of Syria

The governor of Acre, Abdullah Pasha ibn Ali was harboring fugitives of the Egyptian draft, and was said to have refused a request to contribute towards Muhammad Ali's war effort.[1] With these insults as pretext, land and sea forces under the command of Ibrahim Pasha were sent north to besiege Acre in October 1831.[1] The city fell to Ibrahim's army six months later in May 1832. After Acre he continued on to win control of Aleppo, Homs, Beirut, Sidon, Tripoli, and Damascus;[4] the armies sent by the Sultan and various local governors were unable to check Ibrahim's forces,[5] notably at the Battle of Homs, considered to have decided the fate of Syria.

The then-ongoing Tanzimat reforms of Mahmud II had experienced significant difficulties in adopting the innovative military methods of conscription and mass drill then being implemented in European armies, but Mehmed Ali had managed to adopt both.[1][3] Ibrahim's overwhelming success cannot be attributed only to modern organization however. His officers had significantly more experience than their Ottoman counterparts, having borne the brunt of fighting in the Empire's two most recent major wars against the Wahhabi and Greek rebellions, and he attracted significant local support to his cause by calling his campaign one for "liberation from the Turkish yoke."[3] With the provinces of Greater Syria under his control, the Egyptian army continued their campaign into Anatolia in late 1832.[6]

The Battle of Konya

On 21 November 1832, the Egyptian forces occupied the city of Konya in central Anatolia, within striking distance of the imperial capital of Constantinople.[6] The Sultan organized a new army of 80,000 men under Reshid Mehmed Pasha,[6] the Grand Vizier, in a last-ditch attempt to block Ibrahim's advance towards the capital. While Ibrahim commanded a force of 50,000 men, most of them were spread out along his supply lines from Cairo, and he had only 15,000 in Konya.[6] Nevertheless, when the armies met on December 21, Ibrahim's forces won in a rout, capturing the Grand Vizier after he became lost in fog attempting to rally the collapsing left flank of his forces.[1][6] The Egyptians suffered only 792 casualties, compared to the Ottoman army's 3,000 dead, and they captured 46 of the 100 guns with which the army had left Istanbul.[6] The stunning victory at Konya would be the final and most impressive victory of the Egyptian campaign against the Sublime Porte, and would represent the high point of Muhammad Ali's power in the region.[1]

Aftermath

Though no military forces remained between Ibrahim's army and Istanbul, severe winter weather forced him to make camp at Konya long enough for the Sublime Porte to conclude an alliance with Russia, and for Russian forces to arrive in Anatolia, blocking his route to the capital.[4] The arrival of a European power would prove to be too great a challenge for Ibrahim's army to overcome. Wary of Moscow's expanding influence in the Ottoman Empire and its potential to upset the balance of power, French and British pressure forced Muhammad Ali and Ibrahim to agree to the Convention of Kütahya. Under the settlement, the Syrian provinces were ceded to Egypt, and Ibrahim Pasha was made the governor-general of the region.[3]

The treaty left Muhammad Ali a nominal vassal of the Sultan. Six years later, when Muhammad Ali moved to declare de jure independence, the Sultan declared him a traitor and sent an army to confront Ibrahim Pasha, launching the Second Egyptian–Ottoman War.[1]

References

- E.R. Toledano. (2012). "Muhammad Ali Pasha." Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition. ISBN 978-9004128040

- David Howarth. (1976). The Greek Adventure: Lord Byron and other eccentrics in the War of Independence. New York: Atheneum, 1976. ISBN 978-0689106538

- P. Kahle and P.M. Holt. (2012) “Ibrahim Pasha.” Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition. ISBN 978-9004128040

- Trevor N. Dupuy. (1993). "The First Turko-Egyptian War." The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0062700568

- Khaled Fahmy. All the Pasha's Men: Mehmed Ali, His Army and the Making of Modern Egypt. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2002. ISBN 978-9774246968

- Lt. Col. Osama Shams El-Din. "A Military History of Modern Egypt from the Ottoman Conquest to the Ramadan War." United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2007. PDF