Barque

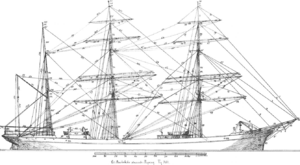

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing vessel with three or more masts having the fore- and mainmasts rigged square and only the mizzen (the aftmost mast) rigged fore and aft. Sometimes, the mizzen is only partly fore-and-aft rigged, bearing a square-rigged sail above.

Etymology

The word "barque" entered English via French, which in turn came from the Latin barca by way of Occitan, Catalan, Spanish, or Italian.

The Latin barca may stem from Celtic barc (per Thurneysen) or Greek baris" (per Diez), a term for an Egyptian boat. The Oxford English Dictionary, however, considers the latter improbable.[1]

The word barc appears to have come from Celtic languages. The form adopted by English, perhaps from Irish, was "bark", while that adopted by Latin as barca very early, which gave rise to the French barge and barque.

In Latin, Spanish, and Italian, the term barca refers to a small boat, not a full-sized ship. French influence in England led to the use in English of both words, although their meanings now are not the same.

Well before the 19th century, a barge had become interpreted as a small vessel of coastal or inland waters, or a fast rowing boat carried by warships and normally reserved for the commanding officer. Somewhat later, a bark became a sailing vessel of a distinctive rig as detailed below. In Britain, by the mid-19th century, the spelling had taken on the French form of barque. Although Francis Bacon used this form of the word as early as 1592,[2] Shakespeare still used the spelling "barke" in Sonnet 116 in 1609. Throughout the period of sail, the word was used also as a shortening of the barca-longa of the Mediterranean Sea.

The usual convention is that spelling barque refers to a ship and bark to tree hide, to distinguish the homophones.

"Barcarole" in music shares the same etymology, being originally a folk song sung by Venetian gondolier and derived from barca - "boat" in Italian.

Bark

In the 18th century, the British Royal Navy used the term bark for a nondescript vessel that did not fit any of its usual categories. Thus, when the British admiralty purchased a collier for use by James Cook in his journey of exploration, she was registered as HM Bark Endeavour to distinguish her from another Endeavour, a sloop already in service at the time. She happened to be a ship-rigged sailing vessel with a plain bluff bow and a full stern with windows.

William Falconer's Dictionary of the Marine defined "bark", as "A general name given to small ships: it is however peculiarly appropriated by seamen to those which carry three masts without a mizzen topsail. Our Northern Mariners, who are trained in the coal-trade, apply this distinction to a broad-sterned ship, which carries no ornamental figure on the stem or prow."[3]

The UK's National Archives state that a paper document surviving from the 16th century in the Cheshire and Chester Archives and Local Studies Service, notes the names of Robert Ratclyfe, owner of the bark "Sunday" and 10 mariners appointed to serve under Rt. Hon. the Earl of Sussex, Lord Deputy of Ireland.

Barque rig

By the end of the 18th century, the term barque (sometimes, particularly in the US, spelled bark) came to refer to any vessel with a particular type of sail-plan. This comprises three (or more) masts, fore-and-aft sails on the aftermost mast and square sails on all other masts. Barques were the workhorse of the golden age of sail in the mid-19th century as they attained passages that nearly matched full-rigged ships, but could operate with smaller crews.

The advantage of these rigs was that they needed smaller (therefore cheaper) crews than a comparable full-rigged ship or brig-rigged vessel, as fewer of the labour-intensive square sails were used, and the rig itself is cheaper. Conversely, the ship rig tended to be retained for training vessels where the larger the crew, the more seamen were trained.

Another advantage is that a barque can outperform a schooner or barkentine, and is both easier to handle and better at going to windward than a full-rigged ship. While a full-rigged ship is the best runner available, and while fore-and-aft rigged vessels are the best at going to windward, the barque is often the best compromise, and combines the best elements of these two.

Most ocean-going windjammers were four-masted barques, since the four-masted barque is considered the most efficient rig available because of its ease of handling, small need of manpower, good running capabilities, and good capabilities of rising toward wind. Usually, the main mast was the tallest; that of Moshulu extends to 58 m off the deck. The four-masted barque can be handled with a surprisingly small crew—at minimum, 10—and while the usual crew was around 30, almost half of them could be apprentices.

Today many sailing-school ships are barques.

A well-preserved example of a commercial barque is the Pommern, the only windjammer in original condition. Its home is in Mariehamn outside the Åland maritime museum. The wooden barque Sigyn, built in Gothenburg 1887, is now a museum ship in Turku. The wooden whaling barque Charles W. Morgan, launched 1841, taken out of service 1921,[4] is now a museum ship at Mystic Seaport[5] in Connecticut. The Charles W. Morgan has recently been refit and is (as of summer, 2014) sailing the New England coast. The United States Coast Guard still has an operational barque, built in Germany in 1936 and captured as a war prize, the USCGC Eagle, which the United States Coast Guard Academy in New London uses as a training vessel. The Sydney Heritage Fleet restored an iron-hulled three-masted barque, the James Craig, originally constructed as Clan Macleod in 1874 and sailing at sea fortnightly. The oldest active sailing vessel in the world, the Star of India, was built in 1863 as a full-rigged ship, then converted into a barque in 1901.

This type of ship inspired the French composer Maurice Ravel to write his famous piece, Une Barque sur l'ocean, originally composed for piano, in 1905, then orchestrated in 1906.

Barques and barque shrines in Ancient Egypt

In Ancient Egypt, barques, referred to using the French word as Egyptian hieroglyphs were first translated by the Frenchman Jean-François Champollion, were a type of boat used from Egypt's earliest recorded times and are depicted in many drawings, paintings, and reliefs that document the culture. Transportation to the afterlife was believed to be accomplished by way of barques, as well, and the image is used in many of the religious murals and carvings in temples and tombs.

The most important Egyptian barque carried the dead pharaoh to become a deity. Great care was taken to provide a beautiful barque to the pharaoh for this journey, and models of the boats were placed in their tombs. Many models of these boats, that range from tiny to huge in size, have been found. Wealthy and royal members of the culture also provided barques for their final journey. The type of vessel depicted in Egyptian images remains quite similar throughout the thousands of years the culture persisted.

Barques were important religious artifacts, and since the deities were thought to travel in this fashion in the sky, the Milky Way was seen as a great waterway that was as important as the Nile on Earth; cult statues of the deities traveled by boats on water and ritual boats were carried about by the priests during festival ceremonies. Temples included barque shrines, sometimes more than one in a temple, in which the sacred barques rested when a procession was not in progress.[6][7] In these stations, the boats would be watched over and cared for by the priests.

Barque of St. Peter

_-_stained_glass%2C_Barque_of_Peter.jpg)

The Barque of St. Peter, or the Barque of Peter, is a reference to the Roman Catholic Church. The term refers to Peter, the first Pope, who was a fisherman before becoming an apostle of Jesus. The Pope is often said to be steering the Barque of St. Peter.[8]

See also

- Barquentine (three masts, fore mast square-rigged)

- Brigantine (two masts, fore mast square-rigged)

- Jackass-barque (three masts, fore mast and upper part of mizzen mast square-rigged)

- Schooner

- Windjammer

- List of large sailing vessels

References

- "barque". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- The Works of Francis Bacon, Volume 8, Cambridge University Press, 2011

- "William Falconer's Dictionary of the Marine". National Library of Australia. 2004-02-03. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- "Sailing Ships". Sailing-ships.oktett.net. Archived from the original on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- "Mystic Seaport homepage". MysticSeaport.org. Archived from the original on 2013-02-04. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- "Egyptian Temples". Odyssey Adventures in Archaeology. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- "Ancient Egypt 2675–332 BCE: Religion: Temple Architecture and Symbolism". Arts and Humanities Through the Eras. BookRags.

- "Ship as a Symbol of the Church (Bark of St. Peter)". Jesus Walk. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

Further reading

- Wilhelmsen, Frederick D. (1956). Omega: Last of the barques. Westminster, Maryland: Newman Press. LCCN 56011411. OCLC 3439968.

External links

| Look up barque in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barques. |