Exocet

The Exocet (French pronunciation: [ɛɡzɔsɛ]; French for "flying fish"[1]) is a French-built anti-ship missile whose various versions can be launched from surface vessels, submarines, helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft. The Exocet saw its first wartime launch during the Falklands War.

| Exocet | |

|---|---|

An AM39 aircraft-launched Exocet | |

| Type | Anti-ship missile |

| Place of origin | France |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1973 |

| Used by | See operators |

| Wars | Iran–Iraq War Falklands War |

| Production history | |

| Designer | 1967–1970: Nord Aviation 1970–1974: Aérospatiale |

| Designed | 1967 |

| Manufacturer | 1979–1999: Aérospatiale 1999–2001: Aérospatiale-Matra 2001–present: MBDA |

| Produced | 1974 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 780 kilograms (1,720 lb) |

| Length | 6 metres (19 ft 8 in) |

| Diameter | 34.8 centimetres (1 ft 1.7 in) |

| Warhead | 165 kilograms (364 lb) |

| Engine | Solid propellant engine turbojet (MM40 Block 3 version) |

| Wingspan | 1.35 metres (4 ft 5 in) |

Operational range | 70-180 kilometres (110 mi; 97 nmi) |

| Flight altitude | Sea-skimming |

| Maximum speed | Mach 0.93 1,148 kilometres per hour (713 mph; 319 m/s) |

Guidance system | Inertial guidance, active radar homing, and GPS guidance |

Launch platform | multi-platform:

|

Etymology

The missile's name was given by M. Guillot, then the technical director at Nord Aviation.[1] It is the French word for flying fish, from the Latin exocoetus, a transliteration of the Greek name for the fish that sometimes flew into a boat: ἐξώκοιτος (exōkoitos), literally "lying down outside (ἒξω, κεῖμαι), sleeping outside".[2]

Description

The Exocet is built by MBDA, a European missile company. Development began in 1967 by Nord as a ship-launched weapon named the MM 38. A few years later Aerospatiale and Nord merged. The basic body design was based on the Nord AS30 air-to-ground tactical missile. The air-launched Exocet was developed in 1974 and entered service with the French Navy five years later.[3]

The relatively compact missile is designed for attacking small- to medium-size warships (e.g., frigates, corvettes and destroyers), although multiple hits are effective against larger vessels, such as aircraft carriers.[4] It is guided inertially in mid-flight and turns on active radar late in its flight to find and hit its target. As a countermeasure against air defence around the target, it maintains a very low altitude during ingress, staying one to two meters above the sea surface. Due to the effect of the radar horizon, this means that the target may not detect an incoming attack until the missile is only 6,000 m from impact. This leaves little time for reaction and stimulated the design of close-in weapon systems (CIWS).

Its rocket motor, which is fuelled by solid propellant, gives the Exocet a maximum range of 70 kilometres (43 mi; 38 nmi). It was replaced on the Block 3 MM40 ship-launched version of the missile with a solid-propellant booster and a turbojet sustainer motor which extends the range of the missile to more than 180 kilometres (110 mi; 97 nmi). The submarine-launched version places the missile inside a launch capsule.

Versions

The Exocet has been manufactured in versions including:

- MM38 (surface-launched) – deployed on warships. Range: 42 km. No longer produced (1970). A coast defence version known as "Excalibur" was developed in the United Kingdom and deployed in Gibraltar from 1985–1997.[5]

- AM38 (helicopter-launched – tested only)[6]

- AM39 (air-launched) – B2 Mod 2: deployed on 14 types of aircraft (combat jets, maritime patrol aircraft, helicopters). Range between 50 and 70 km, depending on the altitude and the speed of the launch aircraft.

- SM39 (submarine-launched) – B2 Mod 2: deployed on submarines. The missile is housed inside a watertight launched capsule (VSM or véhicule Sous marin), which is fired by the submarine's torpedo-launch tubes. On leaving the water, the capsule is ejected and the missile's motor is ignited. It then behaves like an MM40. The missile will be fired at depth, which makes it particularly suitable for discreet submarine operations.

- MM40 (surface-launched) – Block 1, Block 2 and Block 3: deployed on warships and in coastal batteries. Range: 72 km for the Block 2, in excess of 180 km for the Block3.

MM40 Block 3

In February 2004, the Délégation Générale pour l'Armement (DGA) notified MBDA of a contract for the design and production of a new missile, the MM40 Block 3. It has an improved range, in excess of 180 kilometres (97 nautical miles)—through the use of a turbojet engine, and includes four air intakes to provide continuous airflow to the power plant during high-G manoeuvres.

The Block 3 missile accepts GPS guidance system waypoint commands, which allow it to attack naval targets from different angles and to strike land targets, giving it a marginal role as a land-attack missile. The Block 3 Exocet is lighter than the previous MM40 Block 2 Exocet.[7]

45 Block 3 Exocets were ordered by the French Navy in December 2008 for its ships which were carrying Block 2 missiles, namely Horizon-class and Aquitaine-class frigates. These are not to be new productions but the conversion of older Block 2 missiles to the Block 3 standard. An MM40 Block 3 last qualification firing took place on the Île du Levant test range on 25 April 2007 and series manufacturing began in October 2008. The first firing of the Block 3 from a warship took place on 18 March 2010, from the French Navy air defence frigate Chevalier Paul. In 2012, a new motor, designed and manufactured in Brazil by the Avibras company in collaboration with MBDA, was tested on an MM40 missile of the Brazilian Navy.

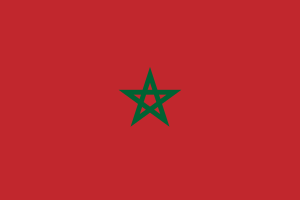

Beside the French, the Block 3 has been ordered by several other navies including that of Greece, the UAE, Chile,[8] Peru,[9] Qatar, Oman, Indonesia and Morocco.[10]

The chief competitors to the Exocet are the US-made Harpoon, the Italian Otomat, the Swedish RBS-15 and the Chinese Yingji series.

Operational history

Falklands War

In 1982, during the Falklands War, Argentine Navy Dassault-Breguet Super Étendard warplanes carrying the AM39 Air-launched version of the Exocet caused damage which sank the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Sheffield on 4 May 1982. Two more Exocets struck the 15,000-ton merchant ship Atlantic Conveyor on 25 May. Two MM38 ship-to-ship missiles were removed from the destroyer ARA Seguí, a former US Navy Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer, and transferred to an improvised launcher for land use.[11] The missiles were launched on June 12 1982 and one hit the destroyer HMS Glamorgan.

- HMS Sheffield

Sheffield was a Type 42 guided missile destroyer commissioned in 1975. On 4 May 1982, Sheffield was at defence watches (second-degree readiness) the southernmost of three Type 42 destroyers when she was hit by one of two AM39 Air-launched Exocet missiles fired by Argentine Super Étendard strike fighters. The second missile splashed into the sea about half-mile off her port beam.[12]

The missile that struck Sheffield impacted on the starboard side at deck level 2, travelling through the junior ratings' scullery and breaching the Forward Auxiliary Machinery Room/Forward Engine Room bulkhead 2.4 metres (7 ft 10 in) above the waterline, creating a hole in the hull roughly 1.2 by 3 metres (3.9 by 9.8 ft). It appears that the warhead did not explode.[13] 20 members of her complement were killed, 26 injured and the loss of Sheffield was a deep shock to the British public and government.

The official Royal Navy Board of Inquiry Report stated that evidence indicates that the warhead did not detonate. During the 4½ days that the ship remained afloat, five salvage inspections were made and a number of photographs were taken. Members of the crew were interviewed and testimony was given by Exocet specialists (the Royal Navy had 15 surface combat ships armed with Exocets in the Falklands War). There was no evidence of an explosion, although burning propellant from the rocket motor caused fires which could not be checked as firefighting equipment had been put out of action.

- SS Atlantic Conveyor

Atlantic Conveyor was a 14,950 ton roll-on, roll-off container ship launched in 1969 that had been hastily converted to an aircraft transport and was carrying helicopters and supplies, including cluster bombs. [14] Two Exocet missiles had been fired at a frigate, but had been confused by its defences and re-targeted the Atlantic Conveyor. Both missiles struck the container ship on her port quarter and warheads exploded either after penetrating the ship's hull,[15] or on impact.[16] Witness Prince Andrew reported that debris caused "splashes in the water about a quarter of a mile away".[17] Twelve men were killed and the survivors were taken to HMS Hermes.

- HMS Invincible

On May 30, two Super Étendards, one carrying Argentina's last remaining Exocet, escorted by four A-4C Skyhawks each with two 500lb bombs, took off to attack the carrier HMS Invincible.[18] Argentine intelligence had sought to determine the position of HMS Invincible from analysis of aircraft flight routes from the task force to the islands[18]. However, the British had a standing order that all aircraft conduct a low level transit when leaving or returning to the ship to disguise her position[19]. This tactic compromised the Argentine attack, which focused on a group of escorts 40 miles south of the main body of ships[20]. Two of the attacking Skyhawks[20] were shot down by a Sea Dart fired by HMS Exeter[18], with HMS Avenger claiming to have shot down the missile with her 4.5" gun (although this claim is disputed)[21]. No damage was caused to any British vessels[18].

- HMS Glamorgan

HMS Glamorgan was a County-class destroyer of the Royal Navy launched in 1964. On 12 June 1982 an MM38 Exocet missile was fired from an improvised shore-based launcher as she was steaming at about 20 knots (37 km/h) 18 nautical miles (33 km) offshore. The first attempt to fire a missile did not result in a launch; on the second attempt, a missile was launched but did not acquire the target. The third attempt resulted in a missile tracking Glamorgan. The incoming Exocet missile was also spotted on Glamorgan[22] and a turn was ordered to present the stern to the missile.

The turn prevented the missile from striking the ship's side and penetrating the hull; instead, it hit the deck coaming at an angle, near the port Seacat launcher, skidded along the deck and exploded, making a 10 by 15 feet (3.0 m × 4.6 m) hole in the hangar deck and a 5 by 4 feet (1.5 m × 1.2 m) hole in the galley below.[22] The blast travelled forwards and down, and the missile body, still travelling forwards, penetrated the hangar door, causing the ship's fuelled and armed Wessex helicopter (HAS.3 XM837) to explode and start a severe fire in the hangar. Fourteen crew members were killed and more wounded.

- Post Falklands war

In the years after the Falklands War, it was revealed that the British government and the Secret Intelligence Service had been extremely concerned at the time by the perceived inadequacy of the Royal Navy's anti-missile defences against the Exocet and its potential to tip the naval war decisively in favour of the Argentine forces. A scenario was envisioned in which one or both of the force's two aircraft carriers (Invincible and Hermes) were destroyed or incapacitated by Exocet attacks, which would make recapturing the Falklands much more difficult.

Actions were taken to contain the Exocet threat. A major intelligence operation was initiated to prevent the Argentine Navy from acquiring more of the weapons on the international market.[23] The operation included British intelligence agents claiming to be arms dealers able to supply large numbers of Exocets to Argentina, who diverted Argentina from pursuing sources which could genuinely supply a few missiles. France denied deliveries of Exocet AM39s purchased by Peru to avoid the possibility of Peru giving them to Argentina because they knew that payment would be made with credit from the Central Bank of Peru. British intelligence had detected the guarantee was a deposit of two hundred million dollars from the Andean Lima Bank, an owned subsidiary of the Banco Ambrosiano.[24][25]

Iran–Iraq War

During the Iran–Iraq War, on 17 May 1987, an Iraqi aircraft initially identified as a Dassault Mirage F1[26] aircraft but was in fact a modified Falcon 50 business jet, [27] fired two Exocet missiles at the American frigate USS Stark.

Both missiles struck the port side of the ship near the bridge. No weapons were fired in defence, the Phalanx CIWS remained in standby mode and the Mark 36 SRBOC countermeasures were not armed. 37 United States Navy personnel were killed and 21 wounded.

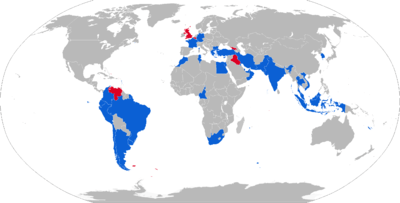

Operators

Current operators

- Argentine Navy – MM38, MM40 and AM39

- Royal Brunei Navy – MM38, MM40

- Brazilian Navy – MM38, MM40 Block 2 and AM39, SM-39

- Cameroon Navy – MM38, MM40 (on P-48S (Bakassi) craft)

- Chilean Navy – AM39, MM40 block-2, MM40 block-3 and SM39 for the Scorpène-class submarine.

- Cyprus Navy – MM40

- French Navy – MM38, MM40, AM39, SM39

- German Navy – To be replaced with the RBS 15.

- Hellenic Navy – MM38, MM40 Block 2/3

- Hellenic Air Force – AM39

- MM38 on Fatahillah class corvette, MM40 Block 2 on Sigma-class corvette and Bung Tomo-class corvette, MM40 Block 3 on Martadinata-class frigate[29]

- Iranian Air Force – Acquired AM39 from Iraqi Mirage F1s; these aircraft sought sanctuary during the second Persian Gulf War.

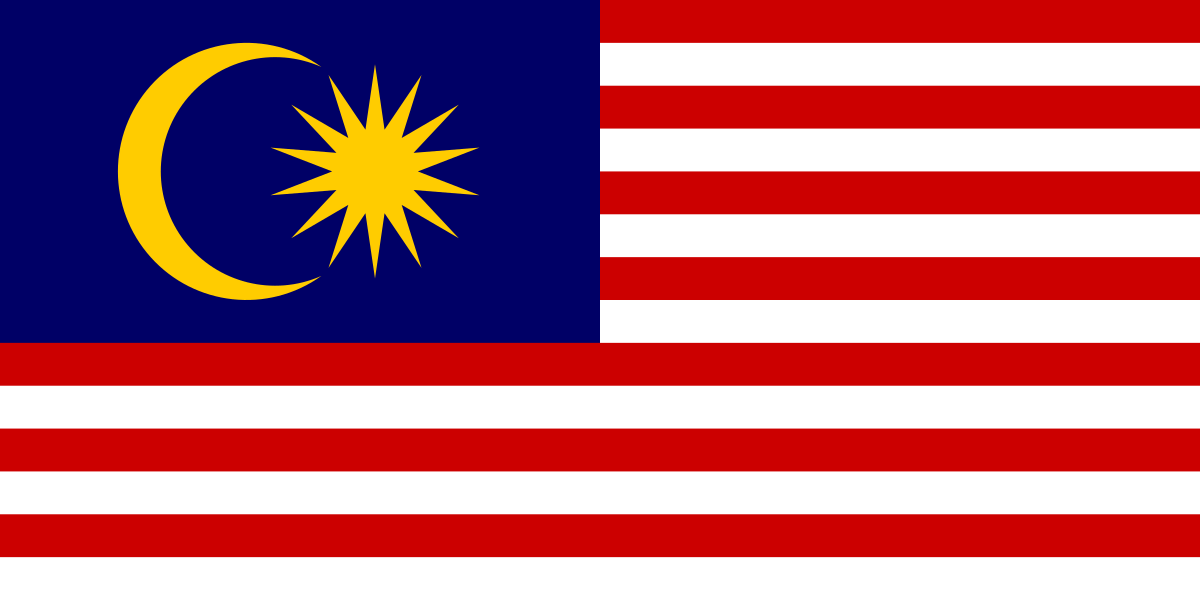

- Royal Malaysian Navy – MM38, MM40 Block 2, MM40 Block 3 and SM39 (on Scorpène-class submarines)[30]

- Royal Moroccan Navy – MM38, MM40 Block 2/3,

- Moroccan Air Force – AM39

- Pakistan Naval Air Arm – AM39 (on Mirage-5V) and on JF17 Thunder naval support fighters)

- Pakistan Navy – SM39 (on Agosta 90B (Khalid)-class submarines), AM39 (on Breguet Atlantic patrol aircraft)

- Peruvian Navy – MM38 on PR-72P-class corvettes, AM39 Block 2 on ASH-3D Sea Kings and Mirage 2000P, MM40 Block 3 on Lupo-class frigates

- Royal Thai Navy – MM38

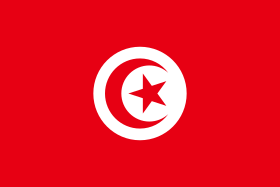

- MM-40 Exocet for the La Combattante III-class fast attack craft[28]

- Vietnam People's Navy MM40 Block 3 on Sigma-class corvette

- UAE Navy MM40 Block 3 on Baynunah-class corvette

Former operators

.svg.png)

- Belgian Navy operated Exocet on its Wielingen-class frigates. These warships were all sold in 2008 to Bulgaria.

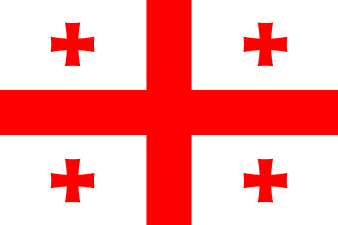

- Georgian Navy

.svg.png)

- Iraqi Air Force – operated Exocet on its Mirage F1, Super Étendard and Super Frelon during the Iran–Iraq War, all retired.

- Royal Navy operated Exocet until the last MM38 armed surface vessel was decommissioned in 2002.

- Venezuelan Air Force – operated Exocet on its Dassault Mirage 50)

- Republic of Korea Navy

Lokata Company

Sometime in 1983, the Lokata Company (a British maker of boat navigation equipment), independently duplicated part of the Exocet's navigation system.[35]

See also

References

- Guillot, Jean; Estival, Bernard (1988). L'extraordinaire aventure de l'Exocet (in French). Brest: Les éditions de la Cité. ISBN 2-85186-039-9.

The missile's name was given by M. Guillot, then technical director at Nord Aviation, after the French name for flying fish.

- Harper, Douglas. "Exocet". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- "Exocet AM.39 / MM.40". Federation of American Scientists. 10 August 1999. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Friedman, Norman (1994). The Naval Guide to World Weapons Systems (Updated ed.). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-55750-259-9. In a recent study by the Russians on the effects of missile boat anti-ship missiles it took three hits to destroy a light cruiser and one to two hits for a destroyer or frigate. Russian missile boat anti-ship missiles have far larger warheads than the Exocet.

- Friedman, Norman. The Naval Institute Guide to World Naval Weapons Systems, 1997–1998. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-55750-268-1. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- Based on the ship launched MM38. Only five tested in 1973 from a Super-Felon helicopter, further development then abandoned for the lighter and smaller AM39. – Pretty, Ronald T. (ed.). Jane's Weapon Systems 1976 (7th ed.). London, UK: MacDonald and Jane's. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-35400-527-2.

- Bolkcom, Christopher; Pike, John (1 April 1993). "Cruise Missiles: The Other Air Breathing Threat". Attack Aircraft Proliferation: Issues For Concern. Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- Scott, Richard (28 September 2016). "Chile begins MM40 Block 3 Exocet retrofits". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- "Perú aprueba 41 millones de dólares para Defensa y se hará finalmente con misiles MM-40 Exocet". Foro Base Naval (in Spanish). 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- "Premier tir de missile Exocet MM40 Block3 par la marine française". Mer et Marine (in French). 19 March 2010. Archived from the original on 22 March 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Scheina, Robert L. (July 2003). Latin America's Wars Volume II: The Age of the Professional Soldier, 1900-2001. Potomac Books Inc. p. 316. ISBN 978-1-57488-452-4. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2016 – via Google Books.

- Narrative of the attack Archived 12 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine, page 6

- Loss of HMS Sheffield - Board of Inquiry (PDF) (Report). Northwood: Commander-in-Chief Fleet. 28 May 1982. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- The Atlantic Conveyor - Before She Was Famous

- Chant, Christopher (2001). Air War in the Falklands 1982. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-84176-293-7.

- "Board of Enquiry (Report) Loss of SS Atlantic Conveyor" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- "Prince Andrew talks of Falklands horror". Glasgow Herald. 14 November 1983. p. 2.

- Lawrence Freedman; Lawrence (King's College London Freedman, University of London UK); Professor of War Studies Lawrence Freedman, Sir (2005). The Official History of the Falklands Campaign: War and diplomacy. Psychology Press. p. 545. ISBN 978-0-7146-5207-8.

- Jerry Pook (15 June 2008). RAF Harrier Ground Attack: Falklands. Pen and Sword. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-84884-556-5.

- David Morgan (2007). Hostile Skies. Phoenix. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-7538-2199-2.

- Ewen Southby-Tailyour (2 April 2014). Exocet Falklands: The Untold Story of Special Forces Operations. Pen and Sword. pp. 238–. ISBN 978-1-4738-3513-9.

- Inskip, Ian (2002). Ordeal by Exocet: HMS Glamorgan and the Falklands War, 1982. Chatham. pp. 160–185. ISBN 1-86176-197-X.

- Briley, Harold (May 2002). "John Nott's Story". Falkland Islands Newsletter. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010.

A remarkable worldwide operation then ensured to prevent further Exocets being bought by Argentina. I authorised our agents to pose as bona fide purchasers of equipment on the international market, ensuring that we outbid the Argentineans. Other agents identified Exocet missiles in various markets and covertly rendered them inoperable, based on information from the French.

- Freedman, Lawrence (1 January 2005). The Official History of the Falklands Campaign: War and Diplomacy. Routledge. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-7146-5207-8. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017 – via Google Books.

- "A las Malvinas en subte". Página/12 (in Spanish). 25 March 2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Formal Investigation into the Circumstances Surrounding the Attack of the USS Stark in 1987

- Leone, Dario (14 July 2019). "How a Modified Iraqi Falcon 50 Business Jet Nearly Destroyed a US Frigate". The National Interest. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "Trade Registers". SIPRI. Archived from the original on 31 January 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- "Latest News: Two Sigma 9113 corvettes more for Indonesia" (PDF). Damen News. No. 7. April 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- "Malaysian Navy's 1st 'Scorpene' sub test fires Exocet missile". Brahmand.com. 4 August 2010. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (9 October 2008). "Fact file: Valour-class frigates". DefenceWeb. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- The Military Balance. International Institute for Strategic Studies. 2013. p. 531. ISBN 978-1-85743-680-8.

- "Refakat Ve Karakol Fi̇losu Komutanliği". Turkish Naval Forces (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- "World Navies Today: Turkey". Hazegray.org. 25 March 2002. Archived from the original on 19 December 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- "Defence ministry 'Exocets' yacht radar". New Scientist: 803. 24 March 1983. ISSN 0262-4079. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Exocet. |

- Manufacturer's Website (in English and French)

- Gallery of photographs of various variants of the Exocet missile (in French)

- Argentine Account of the role of the Exocet in the Falklands War (in English)

- Photos of Exocet damage to USS Stark (in English)

- Testing of Exocet MM-40 Block 3 (in English)

- CSIS Missile Threat | Exocet (in English)