Benito Jerónimo Feijóo y Montenegro

Friar Benito Jerónimo Feijóo y Montenegro (Spanish pronunciation: [beˈnito xeˈɾonimo fejˈxoo]; 8 October 1676 – 26 September 1764) was a Spanish monk and scholar who led the Age of Enlightenment in Spain. He was an energetic popularizer noted for encouraging scientific and empirical thought in an effort to debunk myths and superstitions.

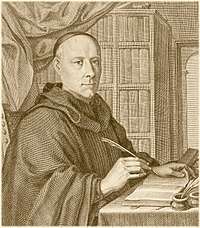

Benito Jerónimo Feijóo | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Feijoo y Montenegro by Juan Bernabé Palomino | |

| Born | October 8, 1676 |

| Died | September 26, 1764 (aged 89) |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | Monk, scholar, essayist |

Biography

He joined the Benedictine order at the age of 14, and had taken classes in Galicia, León, and Salamanca. He later taught theology and philosophy at the University, where he earned a professorship in theology.

He was appalled by the superstition and ignorance in his country, and his works aimed at combating the situation.[1] His fame spread quickly throughout Europe. His revelations excited considerable opposition in certain quarters in Spain, for example from Salvador José Mañer and others; but the opposition was futile, and Feijóo's services to the cause of education and knowledge were universally recognized long before his death in Oviedo.[2]

A century later Alberto Lista said that a monument should be erected to Feijóo, at the foot of which all his works should be burned. He was not a great genius, nor a writer of transcendent merit; his name is connected with no important discovery, but his literary style is clear and not without distinction. He tried to uproot many popular errors, awakened an interest in scientific methods,[3] and is justly regarded as the initiator of educational reform in Spain.[2]

Works

His two famous works, Teatro crítico universal (1726–1739) and Cartas eruditas y curiosas (1742–1760), are multi-volume collections of essays that cover a range of subjects, from natural history and the then known sciences, education, history, religion, literature, philology, philosophy and medicine, down to superstitions, wonders and salient points of contemporary journalistic interest. In the edition of 1777 they occupy nine and five volumes respectively, to which three supplementary volumes must be added. A reprint occurs in volume 56 of the Biblioteca de autores españoles, with an introduction by Vicente de la Fuente. As learning advanced, his writings were relatively relegated to a place of historical and literary interest. The majority of his works were translated into English by Captain John Brett (3 vols., 1777-1780).

Footnotes

- Stanley G. Payne, History of Spain and Portugal (1973) 2:367-71

-

- "Feijoo and his 'Magisterio de la experiencia' (lessons of experience) – Early Modern Experimental Philosophy, University of Otago, New Zealand". Blogs.otago.ac.nz. 2012-10-29. Retrieved 2013-07-24.

References

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Underhill, John Garrett (1920). . In Rines, George Edwin (ed.). Encyclopedia Americana.